Capital History Kiosk Project

They’re easy to spot when you’re walking along any of Ottawa’s busy streets. They’re designed to be recognized.

Our October 13, 2021 presentation is about the traffic control boxes at many of Ottawa’s intersections; not of the drab utility boxes themselves, but about the colourful history lessons that have been applied to them to remind you of what Ottawa used to look like 10, 50, or 100 years ago, and to tell the story of a significant event that took place near each control box.

David Dean has been a professor of History at Carleton University since 2000. He got the kiosk project moving forward in 2015 with utility boxes along Bank Street, to tell the story of the local businesses. This early stage was completed in collaboration with the Workers History Museum and the Carleton Centre for Public History. The Capital History Kiosk Project expanded city-wide in 2017, as part of Canada’s 150th Anniversary celebration.

Danielle Mahon is an MA student as Carleton. She talked about the process of gathering information on each kiosk, and uploading location information on the kiosks to the Capital History website, at www.capitalhistory.ca. Students have also assisted in the project to add QR codes at each traffic box so that pedestrians can scan the code with a cell phone to read more about the history depicted at each box.

Being the national capital, there is no shortage of stories to tell about Ottawa, and fortunately there is no shortage of control boxes. David notes that the city as about 19,000 of them. The kiosk project is expanding as more research is done, so don’t be surprised if you see a new one next time your walking, jogging, or cycling around town.

Visit the HSO YouTube channel for to view the full presentation about the Capital Kiosk Project.

Capital History Kiosk Project

In this presentation, David Dean and Danielle Mahon demonstrate the unique approach to local storytelling through the Capital Kiosk Project.

Project 70,000: The Indochinese Refugee Movement to Canada

Our last presentation before the summer 2021 break took us halfway around the world but the story resonated here in Ottawa in 1979. After seeing stories on the news about the plight of refugees fleeing Cambodia and Laos and Vietnam, Ottawa mayor Marion Dewar anxiously arranged a public meeting at Lansdowne Park to gauge the interest within the city for sponsoring refugees in desperate need. Dewar expected about 500 people to show up, but when she arrived to open the meeting she discovered that 3,000 had arrived to do their part to provide new homes for refugees fleeing war-torn countries.

It is at this point in our story where two of the evening’s three guest speakers enters the picture.

Michael Molloy was the director of refugee policy in Canada from 1976 to 1978 and Senior Coordinator for the Indochinese Refugee Task Force. Canada had never before experienced a refugee crisis of such magnitude, so Mike and his colleagues had no playbook to go by to process refugees and get them safely to Canada.

The second speaker for the evening was Robert Shalka. He was in Thailand and had hoped initially to settle refugees there but realized that Canada was going to have to do its part to find homes for those forced to flee Cambodia and Laos. Robert spoke about processing centres in Singapore, Bangkok and other places in Asia and of the challenges of interviewing refugees, reconnecting separated families, finding resettlement lands in Thailand, or arranging transportation to Canada for refugees, as well as the process in Canada of organizing sponsors.

In 2017, Mike and Bob and two other foreign service offers, members of the Canadian Immigration Historical Society, collected their stories into a book, Running on Empty, which you can order through the McGill-Queen’s University Press website, at mqup.ca.

Last to speak was Rivaux Lay, who was in Thailand during the crisis, a Cambodian refugee himself, contributing as a social worker, translator and teacher’s aide at the refugee camps. You need to hear Rivaux’s story in his own words to fully appreciate what he went through in those horrific years, finally came to Canada, after helping so many others before him.

You can view the June 2021 presentation online via the HSO channel on YouTube.

Project 70,000: Canada Welcomes the Refugees of Southeast Asia 1975-1980

Michael Molloy & Robert Shalka, co-authors of "Running on Empty", plus Rivaux Lay, a former Cambodian refugee, spoke on June 16, 2021 about the efforts to welcome Indochinese refugees to the City of Ottawa in the 1970s.

The Corporation of Bytown

28 July 1847

Municipal elections don’t get the respect they deserve in Canada. Invariably, far fewer people vote in them than they do in their provincial or federal counterparts. And Ottawa’s municipal elections are no exception. In the 2018 election, the percentage of registered voters who actually voted was less than 43 per cent. In comparison, two-thirds of registered Canadian voters exercised their franchise in the 2015 federal election. Reasons for municipal voters’ apathy include a lack of awareness about what local candidates stand for, and a feeling that municipal governments don’t matter very much. Two hundred years ago, the sentiment was very different. The quest for independent, municipal governments responsible to local ratepayers was a potent political issue that divided communities.

When British sympathizers fled northward following the American Revolution, they brought with them the democratic processes that they had grown up with in New York, Pennsylvania, and New England. These included elected municipal officials and town hall meetings where local issues were publicly thrashed out. For British military leaders in what was to become Canada, such democratic ideas were anathema. After all, hadn’t democracy led to the loss of the southern American colonies? In their view, free elections, even at the local level, threatened peace and order. What was needed was the firm guiding hand of Crown-appointed magistrates and officials.

In 1791, Quebec was divided into two parts under the Constitutional Act—Lower Canada where the French civil code and customs prevailed and Upper Canada where British common law and practices were introduced to accommodate the many English-speaking, United Empire Loyalists. However, General Simcoe, Upper Canada’s first lieutenant governor, was loath to permit democratic notions from taking root in Canada. He was appalled when one of the first acts of the Assembly of Upper Canada was to approve town meetings for the purpose of appointing local officials. He stalled and prevaricated, favouring instead a system of municipal government guided by justices of the peace appointed by the Crown. It took decades for real democracy to be introduced. In the interim, power at both the provincial and municipal level was tightly controlled by a small group of powerful merchants, lawyers and Church of England clergymen who became known as the Family Compact.

Cracks in this authoritarian structure began to show in 1832 when Brockville won the right to have an elected Board of Police. Other towns quickly followed suit. In 1834, the town of York became the city of Toronto under its radical first mayor William Lyon Mackenzie, and held direct elections for its mayor and its aldermen. In 1835, a new Act of the Provincial Assembly transferred municipal powers from the justices of the peace to elected Boards of Commissioners. However, this democratic reform was repealed amidst the Rebellions of 1838 by resurgent conservative forces who managed to frame the debate as between order and loyalty to the Crown on one side and disorder and republican disloyalty on the other.

This set the stage for Lord Durham’s famous investigation into the causes of the Rebellions and possible solutions. In his Report made public in 1839, Durham recommended the introduction of responsible government in Canada with ministers responsible to an elected assembly rather than appointed by the Crown. He also said that “the establishment of a good system of municipal institutions throughout the Province [Upper Canada] is a matter of vital importance. In 1841, the District Council Act was passed by Parliament. It was a compromise between conservative (Tory) forces that wanted to maintain central control over local affairs in order to ward off republicanism and radical (Reform) forces that wanted total local self-government. Districts would be governed by a warden appointed by the Crown and a body of elected councillors. While some municipal officials were appointed by the councillors, certain positions, including that of treasurer, would continue to be appointed by the Crown. It wasn’t until the “Baldwin Act” of 1849 (named for Robert Baldwin) that municipalities in Upper Canada were granted wide powers of self-administration.

The broad forces that were in play in Upper Canada were also in play in little Bytown which was established in 1826 by Lieutenant-Colonel By, the architect of the Rideau Canal. Initially, it was a military town where the British Ordnance Department was the dominant player in the local administration and a major landowner. In the 1830s, Bytown became part of Nepean Township and subsequently the “capital” of the Dalhousie District with an appointed warden. In addition to Bytown, other communities represented in Dalhousie District included Nepean, Gloucester, North Gower, Osgoode, Huntley, Goulbourn, Marlborough, March, Torbolton, and Fitzroy. It was a cumbersome arrangement owing to the size of the district and poor roads.

On 28 July 1847, Bytown gained new status when the Governor General gave his assent to “An Act to define the limits of the Town of Bytown, to establish a Town Council therein, and for other purposes.” Bytown was divided into three wards, with elections held in mid-September for seven town councillors—two from each of North and South Wards and three from West Ward. North and South Wards encompassed Lower Bytown, the home of mainly working class, Roman Catholic, Irish and French settlers. West Ward contained Upper Bytown, the smaller of the two Bytowns, and the home of the upper-class, Protestant, English elite. Given these demographics, Lower Town was broadly Reform territory, while Upper Town was a Tory bastion.

With eligible voters limited to male ratepayers, there weren’t many voters—only 878 men voted in that first Bytown election. Voting was also public. A secret ballot wasn’t introduced until the Baldwin Act was passed two years later. At the time, a secret ballot was widely perceived as being cowardly and a voting method that promoted political hypocrisy. Elected were Messrs. Bedard and Friel from North Ward, Messrs. Scott and Corcoran in South Ward and Messrs. Lewis, Sparks and Blasdell in West Ward. With the four elected from the North and South Wards all reformers, they held a narrow one-vote majority on Council over the three Tory victors elected in West Ward. At the first session of Council, John Scott was elected Bytown’s first mayor by the seven elected councillors who split down political lines: four Reformers versus three Tories.

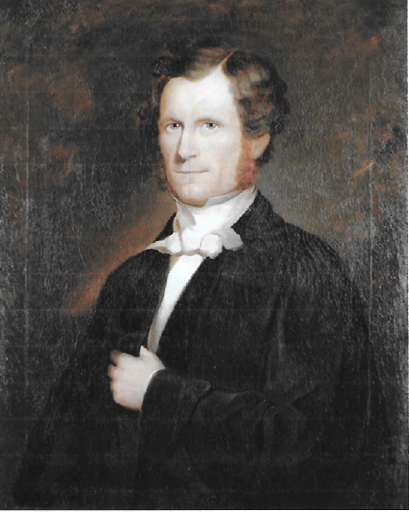

Portrait of John Scott, First Mayor of Bytown, 1848 by William Sawyer, City of Ottawa.In January 1848, John Scott was also elected to the Provincial Parliament as the member for Bytown—this was an era when politicians could hold multiple elected posts simultaneously. In the second municipal election held the following April, Scott chose not to run leading to the election of Tory John Bower Lewis as the second Mayor of Bytown. In 1849, fellow Tory, Robert Hervey, was chosen as Mayor.

Portrait of John Scott, First Mayor of Bytown, 1848 by William Sawyer, City of Ottawa.In January 1848, John Scott was also elected to the Provincial Parliament as the member for Bytown—this was an era when politicians could hold multiple elected posts simultaneously. In the second municipal election held the following April, Scott chose not to run leading to the election of Tory John Bower Lewis as the second Mayor of Bytown. In 1849, fellow Tory, Robert Hervey, was chosen as Mayor.

Hervey’s term in office was marred by two major political events—the Stony Monday riots in September 1849 in which Tories and Reformers came to blows, inflamed by Hervey’s own partisan actions and rhetoric, and the disallowance of the very Act of Parliament that had incorporated Bytown two years earlier.

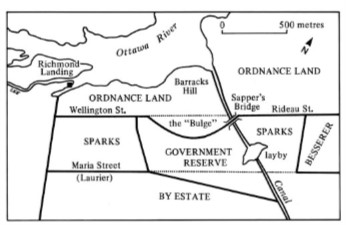

The disallowance of the Act has its roots in a dispute between the Town Council and the Ordnance Department. Under its Act of Incorporation, Bytown had the right to expropriate land. Using this power, the Town Council expropriated a strip of Ordnance property along Wellington Street for the purpose of continuing the street “over the hill between the two towns to meet Rideau Street, in a direct line” at Sappers’ Bridge. At that time, Wellington Street made a bulge around the base of Barrick Hill (later known as Parliament Hill). But with the construction of Sparks Street immediately south of Wellington Street to Sappers’ Bridge following the settlement of another dispute over the ownership of the Government Reserve between Ordnance and Nicholas Sparks in Sparks’ favour, Town Council wanted to straighten Wellington Street. According to the Packet newspaper, the piece of land was “of no value” to the Ordnance Department but was “essential to preserve the uniformity of Wellington Street.”

The Town went ahead and straightened the street over the strenuous objections of the Ordnance Department. Ostensibly, Ordnance claimed that the property was necessary for possible future defensive works. The Packet thought the dispute was caused by the “avarice of one or two self-interested individuals” in Ordnance. In late September 1849, rumours started to circulate that the Home Government in London was about to overturn Bytown’s Act of Incorporation passed by the Canadian Parliament and assented to by the Governor General two years earlier. Fearing this possibility, Councillor Turgeon (a future Mayor of Bytown) proposed repealing the offending By-law that had expropriated the land.

It was to no avail. In late October, the hammer came down. Bytown’s Act of Incorporation was officially disallowed by the British Government in the name of Queen Victoria at the request of the Ordnance Department. Bytown’s politicians were thunderstruck. The news “occasioned no little hub-bub,” said the Packet. “The shock was a dreadful one.” Nobody knew what it meant practically. While “magisterial business” would devolve to the Dalhousie District magistrates, what about other business? Could Bytown pay its bills? What about staffing? The town was described as being in “a bad state” with everything “topsy-turvy.” The Packet fumed at the intrusion of the Home Government in London into a “parish,” i.e. local, matter, and darkly threatened it would be a new argument for the Annexationists (those who wanted the United States to annex Canada).

Map of Ottawa, c. 1840 showing Ordnance land and Wellington Street. Nicholas Sparks, another major landowner, successfully fought the Ordnance Department for the return to him of the Government Reserve Land. This allowed for the development of Sparks street to Sappers’ Bridge by 1849. Taylor, John 1986. “Ottawa, An Illustrated History,” James Lorimer & Company, Toronto.To make matters worse, the Ordnance Department erected a fence across Wellington Street close to Barrick Hill blocking passage of residents to Sappers’ Bridge. Fortunately, there was an alternate route down Sparks Street. The Packet raised its rhetoric called the street closure “a petty act of tyranny inflicted on the habitants of our Town.” It added, “If anything was every calculated to create in the breasts of the inhabitants of this Town an indignant opposition to the British Crown, it is the blocking of one our principal streets.”

Map of Ottawa, c. 1840 showing Ordnance land and Wellington Street. Nicholas Sparks, another major landowner, successfully fought the Ordnance Department for the return to him of the Government Reserve Land. This allowed for the development of Sparks street to Sappers’ Bridge by 1849. Taylor, John 1986. “Ottawa, An Illustrated History,” James Lorimer & Company, Toronto.To make matters worse, the Ordnance Department erected a fence across Wellington Street close to Barrick Hill blocking passage of residents to Sappers’ Bridge. Fortunately, there was an alternate route down Sparks Street. The Packet raised its rhetoric called the street closure “a petty act of tyranny inflicted on the habitants of our Town.” It added, “If anything was every calculated to create in the breasts of the inhabitants of this Town an indignant opposition to the British Crown, it is the blocking of one our principal streets.”

Fortunately, municipal business was quickly regularized with the passage of the Baldwin Act, which allowed towns and cities to incorporate, and the holding of new Bytown Town Council elections in January 1850. With John Scott re-entering municipal politics and his election along with a majority of Reform councillors, Scott was re-elected Mayor of Bytown. Consequently, Scott has the honour of twice being the first Mayor of Bytown. The new Council presented “a humble Petition to the Master General and Board of Ordnance, praying that the Hon. Board may be pleased to grant the use of a space of land opposite Wellington Street to be used for street purposes.” Despite the begging, Ordnance refused to budge.

Residents began to wonder if there was something shady going on. One writer to the Packet in 1851 thought that the Corporation was conspiring in favour of Sparks Street merchants to keep traffic routed down this street rather than negotiating for the re-opening of Wellington Street. Finally, in June 1853, almost four years after the road was closed, Ordnance relented. But its terms were steep: the removal of the fence would be at Bytown’s expense; ownership of the strip of land would remain vested in Her Majesty; the road would be closed on May 1st every year to assert the Queen’s right; Bytown would pay a nominal rent of 5/- per year (5 shillings); no buildings could be erected on this strip of land; and Ordnance reserved the right to resume possession should it feel necessary to do so.

In time, the whole issue became moot when the Ordnance Department dropped its plans to fortify Barrick Hill. On January 1st, 1855, the City of Ottawa, formerly Bytown, was incorporated. One year later, under the Ordnance Lands Transfer Act, ownership of ordnance land in Bytown, and elsewhere, was transferred to the Province of Canada.

Sources:

Canada, Department of the Secretary of State, 1873. Report for the Year Ending 30 June 1873, Appendix A., Department of the Interior, Ordnance Lands Branch, Ottawa.

Durham, Lord, 1839. Report on British North America, Institute of Responsible Government, https://iorg.ca/ressource/lord-durhams-report-on-british-north-america/#.

Elections Canada, 2018. Estimation of Voter Turnout by Age Group and Gender at the 2015 General Election, http://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=res&dir=rec/part/estim/42ge&document=p1&lang=e#e1.

Mika, Nick & Helma, 1982. Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa, Belleville: Mika Publishing Company.

Owens, Tyler, 2016. “A Mayor’s Life: John Scott, First Mayor of Bytown (1824-1857),” Bytown Pamphlet Series, No. 99, Historical Society of Ottawa.

Packet (The) & Weekly Commercial Gazette, 1847. “Prorogation of Parliament,” 31 July.

—————————————————–, 1847. “The Corporation Election.” 18 September.

—————————————————–, 1849. “Bytown Corporation,” 20 September.

—————————————————–, 1849. “The Town of Bytown,” 20 October.

—————————————————–, 1849. “The Ordnance Department And The People Of Bytown,” 13 November.

—————————————————–, 1849. “No Title,” 22 December.

—————————————————–, 1850. “The Elections,” 2 February.

—————————————————–, 1850. “Vote By Ballot, Etc.” 23 February.

—————————————————–, 1850. “Town Council Proceedings,” 23 February.

—————————————————–, 1851. “Queries Addressed To No One In Particular,” 21 June.

—————————————————–, 1853. “No Title,” 11 June.

Shortt, Adam & Doughty, A.G. Sir, 1914. Canada and its Provinces : a history of the Canadian people and their institutions, Volume 18, Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Company.

Taylor, John H. 1986. Ottawa: An Illustrated History, Toronto: James Lorimer & Company.

Whan, Christopher, 2018, “Voter turnout for Ottawa’s municipal elections up from 2014,” Global News, 23 October.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Day My Students Met Mandela: Nelson Mandela's Remarkable 1998 Visit to Ottawa

Wendy Alexis shared stories and memories with us on February 10, 2021, about the day that Nelson Mandela visited the Canadian Tribute to Human Rights monument in Ottawa.

Rawlson King Recounts Journey

The speaker for the HSO presentation on February 12, 2020, not only brought to our event a more culturally diverse crowd than usual, but also a younger crowd. Rawlson King has recently become an inspiration not only for young Ottawans, but also to Ottawans of any culture who feel marginalized and who look up to people like Rawlson to provide a voice for their concerns and hopes in the city.

Rawlson was elected as Ottawa’s first black councillor in a 2019 municipal by-election in Ward 13.

The successful campaign for councillor propelled Rawlson into one of the most challenging jobs in the City of Ottawa. Rideau-Rockcliffe Ward, which wraps around the former City of Vanier, includes some of Ottawa’s richest people (in Rockcliffe Park), but is also home to some of Ottawa’s poorest, as well (in Overbrook).

Rawlson made it clear in his presentation that he wants to represent all Ottawans in his ward fairly, but how does one navigate a course of reconciliation in a ward with such divergent paths?

It is fitting that Rawlson had the opportunity to speak to us in February, which is Black History Month in Canada. History is important, Rawlson noted, because it helps marginalized people “go forward, guided by the past.”

As Canadians, we look to the past and see our nation as a safe haven for freed or escaped slaves from the U.S., but in the earliest days of Upper Canada, slave owners arriving as Loyalists at the end of the American Revolution could continue to own slaves 25 and older until each slave’s death.

Those under 25 became free at 25, but with no social network in place to provide jobs and education. Slavery was ended across the British Empire in 1834, but freedom from servitude didn’t necessarily mean freedom of opportunity. Even into the 1930s, the Ku Klux Klan thrived in many Canadian communities, using fear to diminish Canadians of black heritage.

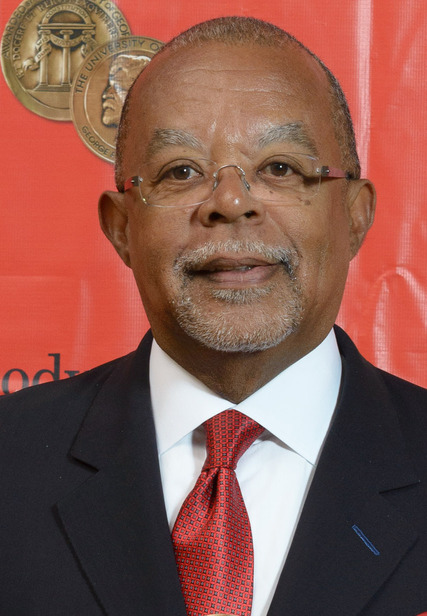

King counts U.S. writer Henry Louis Gates as a key influence.Today we call this same intimidation “erasure”, and Rawlson said he wants to do what he can to erase erasure. To this end, Coun. King read from a book, Talkin’ That Talk, by Henry Louis Gates Jr., which inspired him to join a local residents group, and later to run for the position of school board trustee. The proposed closure of a school in his ward, made up mostly of minority cultures and with one of the lowest graduation rates in the city, encouraged Rawlson to help define a “coherent poverty reduction strategy to help marginalized people gain access to public services and affordable housing.”

King counts U.S. writer Henry Louis Gates as a key influence.Today we call this same intimidation “erasure”, and Rawlson said he wants to do what he can to erase erasure. To this end, Coun. King read from a book, Talkin’ That Talk, by Henry Louis Gates Jr., which inspired him to join a local residents group, and later to run for the position of school board trustee. The proposed closure of a school in his ward, made up mostly of minority cultures and with one of the lowest graduation rates in the city, encouraged Rawlson to help define a “coherent poverty reduction strategy to help marginalized people gain access to public services and affordable housing.”

Rawlson spent a few moments to tell us of his own family’s history. Rawlson’s mom had to work hard to earn a scholarship to pay her way through teacher’s college in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, where black people faced difficulties entering the workforce.

Both his parents were trained as teachers, but neither could find work in a Canadian school. Rawlson’s mom had to take a job in a paint factory in North York when she came to Canada.

Canada’s cautious acceptance of African and Caribbean peoples has helped define Rawlson as an opponent of erasure in our society today. He feels that young Canadians of minority cultures can oppose it through “economic inclusion”. Ottawa’s city council must do its part, he said, through “policies that focus on human potential.”

Rawlson didn’t get a chance to answer all the questions posed to him after the talk. But he assured those who didn’t get time, that he can always be contacted through his city e-mail address.

Thank you to Rawlson for a most enlightening and positive presentation, and thanks also to fellow councillor Tim Tierney of Ward 11, Beacon Hill-Cyrville, who introduced the evening’s guest speaker. The event drew other prominent members of the region’s black community, including Hull-Aylmer Liberal MP Greg Fergus, Black History Ottawa president Jean Girvan and Tom Barber, descendant of one of Ottawa’s first black residents, the renowned horse trainer Paul Barber.

Ottawa's Centenary

16 August 1926

In 2026, Ottawa will celebrate its bicentenary, marking two hundred years from when General George Ramsey, 9th Earl of Dalhousie and Governor General of British North America, wrote to Lieutenant-Colonel John By advising By of his purchase of land for the Crown that contained the site of the head locks for the proposed Rideau Canal on the Ottawa river, and the suitability of the locality for the establishment of a village or town to house canal workers. Lord Dalhousie asked Colonel By to survey the land, divide it into 2-4 acre lots and rent them to settlers, with preference to be given to half-pay officers and respectable people. The rough-hewn community, which was subsequently hacked out of a hemlock and cedar forest, was quickly dubbed Bytown. Its name was changed to Ottawa in 1855, and two years later the town was selected as the capital of the Province of Canada by Queen Victoria.

To celebrate the centenary of its founding by Col. By, the City of Ottawa had a week-long, blow-out extravaganza in the summer of 1926. Although the official opening of the celebrations was on Monday, 16 August 1926, the fun actually began two days earlier on the Saturday with a range of sporting events wide enough to please the most die-hard sports fanatic. The Capital Swimming Club staged a centennial regatta in the Rideau Canal opposite the Exhibition Grounds—a daring event given the poor quality of Canal water. Swimmers from across Canada participated with five Dominion championships at stake. At Cartier Square on Elgin Street, four soccer teams competed for the McGiverin Cup with the Ottawa Scottish emerging the victor, beating the Sons of England with a 5-2 score in the finals. Also featured that day were track and field events, cycling, golf, baseball, tennis and a cricket match at the Rideau Hall cricket pitch.

The following day, there was a huge Garrison Church parade involving 3,000 soldiers including local regiments as well as the Queen’s Own Rifles from Toronto and the Royal 22nd Regiment from Quebec City who had been quartered in tents on the grounds of the Normal School on Elgin Street (now the Heritage Building of the Ottawa City Hall). The troops marched from downtown to Lansdowne Park where 15,000 people crowded into the stands for divine services. More than 50,000 people watched the soldiers march through the streets of Ottawa. That evening the band of the “Van Doos” gave a concert that was broadcast from the Château Laurier hotel.

Devlin Furs’ Float, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025130.

Devlin Furs’ Float, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025130.

The official opening ceremonies took place on the Monday morning on Parliament Hill in front of cheering thousands and “in the shadow of the nearly completed “‘Victory Tower.’” (The name for the Centre Block didn’t officially become the “Peace Tower” until the following year—the 60th anniversary of Confederation.) After much military pomp and pageantry, Sir Henry Drayton, delivered the opening speech in the absence of the Prime Minister, Arthur Meighan. He welcomed visitors to the Capital in the name of the Dominion of Canada. Mayor John Balharrie also greeted visitors and former Ottawa residents who had come home for the celebrations. To symbolized the granting to them of the “freedom” of the city, he released a coloured balloon that carried aloft a four-foot golden key. Messages of congratulations flooded into Ottawa from near and far. Three Governors General—Aberdeen, Connaught and Byng—sent telegrams, as did the Lord Mayor of London, and Jimmy Walker, the controversial and flamboyant Mayor of New York. Civic, provincial and federal politicians from across Canada did likewise.

After the official opening, sporting events occupied the rest of the day. That night, there was a military display and tattoo involving troops from all services in from of 12,000 spectators at Lansdowne Park. The chief feature of the night was the staging of a mock battle scene. As searchlights played over the field, the soldiers re-enacted the crossing of the “Hindenburg” line by Canadian troops in 1918. The mock machine gun action and field bombardment was apparently very realistic. So much so that many veterans experienced flash-backs of their time in the trenches. Also featured that night was a performance of the 1,000 voice Centenary Choir, platoon drills by the Royal 22nd Regiment, and gymnastics displays by cadets.

A highlight of Tuesday, the second day of the Centenary celebrations, was the unveiling of a stone memorial dedicated to Colonel By in a small a park located on the western side of the Rideau Canal just south of Connaught Square opposite Union Station. To the strains of Handel’s Largo, played by the band of the Governor General’s Foot Guard, the memorial, which was covered by a Union Jack, was unveiled at noon. Mayor Balharrie presided. More than 2,000 people witnessed the solemn event. The bronze plaque on the side of the stone, which was intended to be the cornerstone of a much larger memorial, bore the inscription 1826-1926 In Honour of John By, Lieutenant Colonel of the Royal Engineers. In 1826 he founded Bytown, Destined to Become the City of Ottawa, Capital of the Dominion of Canada. This memorial was unveiled in Centenary Year. (A larger memorial was never built. A statue of Colonel By sculpted by Joseph-Émile Brunet was eventually commissioned by the Historical Society of Ottawa and was erected in Major’s Hill Park in 1971.)

At Lansdowne Park, a multi-day western rodeo and stampede commenced with over 200 horses, 100 cattle, and dozens of cowboys from western Canada and the United States. Log rolling competitions took place on the Canal. That evening, an historical pageant was held involving 2,000 actors from service groups, theatre groups, and drama schools. The pageant began with a prologue depicting Confederation with Miss Canada seated on a throne exchanging greetings with Misses Provinces. After pledges of mutual support and loyalty, the provinces curtsied to Canada. This was followed by tableaux representing scenes from Ottawa’s history, including “The Spirit of the Chaudière,” depicting the region before the arrival of Europeans, “The Coming of the White Man,” “Pioneer Settlers,” “The Lumber Industry,” “Bytown and its Early Inhabitants,” “The First Election,” “Naming of the Capital,” “The Fathers of Confederation,” and, a finale where all joined together with the Centenary Choir to sing a closing anthem. The massed 1,000-member Choir accompanied by the G.G.F.G. band also performed a number of popular songs including, O Canada, Land of Hope and Glory, Alouette, Indian Love Song, and, of course, God Save the King.

The pageant got a mixed review. The Ottawa Citizen opined that it provided a “felicitous treatment of the historical episodes chosen for presentation,” but there was “room for improvement.” However, on balance, the pageant was “stimulating and educative.” The dancing was described as “effective.”

After the performance, street dancing was held from 11pm to 2am on O’Connor Street between Albert Street and Laurier to the tunes of two jazz orchestras. With the crush of people, there was little actual dancing though things got a bit better on subsequent nights. With massive crowds downtown, there was some minor trouble. The police arrested a number of young men for setting off firecrackers in the streets. Some had placed “torpedoes” on the street-car tracks that caused “terrific successive explosions” as the trams went over them. Police also acted to curb dangerous driving on the crowded city thoroughfares. Reportedly, louts also molested young women. Generally speaking, however, the street partying was carried out in good humour. A dozen youths organized an impromptu game of leap frog on Sparks Street between Bank and Elgin Streets.

Wednesday, 18 August, was declared a civic holiday by Mayor Balharrie, and more commemorative plaques were unveiled. In addition to non-stop sporting events, rodeo competitions and other fun activities at the Exhibition Grounds, one thousand guests attended a garden party at Rideau Hall. Although Lord Byng had left Ottawa to return to Britain, his term of office as governor general having just ended, he had given permission for the residence to be used as the venue for the civic birthday party celebration. Mayor Balharrie provided a massive four-tier cake decorated with silver foliage and tiny silver cupids. Guests received little boxes of cake bearing the inscription “A souvenir of Ottawa’s Centenary with the compliments of Mayor J. P. Balharrie.”

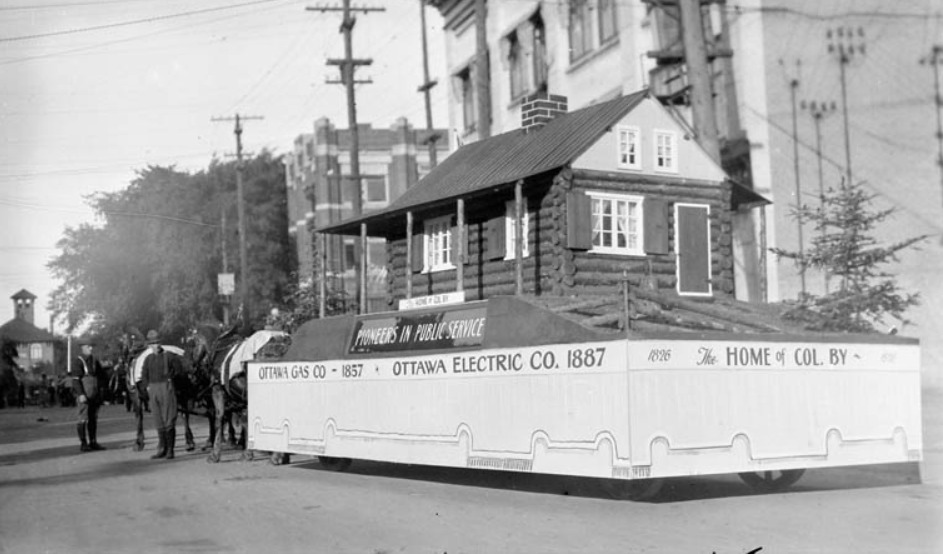

Float of the Ottawa Electric Company, Col. By’s Home, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025127.

Float of the Ottawa Electric Company, Col. By’s Home, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025127.

That evening, Ottawa’s merchants and businesses held the second of the week’s three parades. Starting in the Byward Market and ending at Lansdowne Park, the parade highlighted milestones of Ottawa’s commercial progress over the previous one hundred years. Among the many entries, the Producers’ Dairy’s float featured a huge milk bottle and milk maids. Camping equipment in 1826 and 1926 was the theme of the Grant Holden and Graham entry. Also in the parade was the largest shoe ever manufactured in Canada with six little girls seated inside it, courtesy of Ottawa’s boot and shoe stores. Representing the Ottawa Department Stores Association, four white horses with attendants dressed in white and yellow uniforms pulled a float bearing eight young women in long gowns. Not to be outdone, the A. J. Freiman entry, which was decorated in silver and flowers, was drawn by six white horses with six attendants dressed in white and blue livery. On board were five young ladies wearing period costumes. The Ottawa Electric Company float consisted of an (inaccurate) replica of Colonel By’s house. Instead of a pioneer’s log home as depicted, the Colonel’s actual home was made of stone.

With amusements and events continuing at the Exhibition Grounds, Thursday’s highlight was an “old timers’ parade. In front of immense crowds, historical floats, three bugle bands, three brass bands and one band of bagpipers wended their way slowly from the Byward Market, along Rideau and Sparks Streets before heading down Bank Street to Lansdowne Park. Old-time vehicles on display included an 1897 Oldsmobile and penny-farthing bicycles. Firefighters dressed in the red outfits of yore pulled hand reels or drove antique horse-pulled engines including the “Conqueror,” Ottawa first fire engine. There were also historical tableaux depicting the early days of the Ottawa Valley and Bytown, including Champlain and his men, the arrival of the Jesuits, the establishment of the first white settlement in the region by Philemon Wright, and the beginning of the lumber industry. Guests of honour in the parade included veterans from the Fenian Raids, the South African War and the Great War.

Ottawa Firefighters with hand reels, “Old-Time Pageant,” Ottawa Centenary, August 1926, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025131.

Ottawa Firefighters with hand reels, “Old-Time Pageant,” Ottawa Centenary, August 1926, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025131.

Centenary celebration wound down on the weekend but not before the finals of the stampede, more street dancing, this time in Hintonburg, more sporting activities, and a “Venetian Nights” boating event held on the Rideau Canal.

For those who hadn’t had their fill of fun and games, the Central Canada Exhibition opened immediately after the official ending of the centenary fun, prolonging the excitement for another week.

Both of Ottawa’s major newspapers covered in detail highlights of Ottawa’s first hundred years and centenary events, with each publishing extended supplements. The Evening Citizen boasted that its edition of 16 August weighed in at more than two pounds. It’s rival, The Ottawa Evening Journal, ran a close second. In one regard, however, the Journal went one step further by publishing a fascinating prospective view of what Ottawa might look like on its bicentenary in 2026. Some of its guesses look pretty accurate. It predicted that Ottawa would have a population of 975,000 (actual number 934,240 in 2016) and that it would annex neighbouring communities. It also correctly forecast the elimination of the above-ground, cross-city train tracks and the replacement of the tram lines with buses. It even predicted a tunnel between LeBreton Flats and downtown used by electric trains!

Not surprisingly, however, the crystal-ball gazers got a lot of things wrong. The newspaper predicted that Canada would have a population of 100 million by 2026, and that the airplane would effectively eliminate the automobile as a mode of transportation. The paper also postulated that after decades of delay the great Georgian Bay Ship Canal would finally be completed in 1982, almost eighty years after the idea was first proposed, thereby making Ottawa a deep-water port with direct access to the Atlantic Ocean. As well, given the region’s cheap hydro-electric power, the Journal envisaged a massive expansion of manufacturing in the Ottawa area, forecasting that the Capital would become the home of the largest Canadian plant for the manufacture of pleasure, commercial and air taxicabs. It also predicted the emergence of a large furniture manufacturing industry in Chelsea in West Quebec, and the construction of immense iron ore smelters in Ironside, just north of the old city of Hull, to process iron ore mined in the Laurentians.

For the Journal, the demise of manufacturing and the conversion of Ottawa into the primarily white-collar city that it is today were unimaginable.

Sources:

The Ottawa Evening Citizen, 1926. Various issues, 14-24 August.

The Ottawa Evening Journal, 1926. Various issues, 14-24 August.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa's Royal Swans

28 June 1967

In Britain, there has been an association between the monarchy and mute swans (Cygnus Olor) that dates back to the twelfth century. Traditionally, the Crown claims ownership of all mute swans in open water in England and Wales. The monarch can, however, give the privilege of owning swans to others. In 1483, King Edward IV ruled that only the gentry owing land worth more than five marks (£3. 7s. 6d.) could own “swannes.” Today, other than the Crown, only three groups hold the privilege of owning the waterfowl—the Company of Vintners and the Company of Dyers, who received the right in the 1460s, and the Ilchester family of Abbotsbury, Dorset. The Ilchester family gained the privilege when it acquired property previously owned by Benedictine monks following the dissolution of the monasteries during the sixteenth century by King Henry VIII. Today, the Queen’s swan rights are only enforced over part of the Thames River. Each year, at the ceremonial “Swan Upping,” held during the third week in July, young swans, called cygnets, are rounded up on the river between the towns of Sunbury and Abingdon and distributed among the Crown and the two Companies. In the old days, the beaks of the swans going to the Companies were marked, one nick for Dyers’ birds and two nicks for Vintners’ birds. Birds owned by the Crown were left unmarked. Today, instead of nicking the beaks, the birds are banded.

You might wonder why all the bother. The purpose of the modern “Upping” is not so much about ownership but rather about monitoring the health of the mute swan population on the Thames. It’s also about having fun, dressing up in fancy uniforms and getting out on the water in traditional wooden skiffs on a warm, summer’s day. Back in medieval times, however, it was very serious business. Swans were a valuable commodity, and were eaten as poultry, much like chickens, ducks and geese are today. Swan was the fowl of choice of the aristocracy at feasts. But for some reason, swan flesh went out of fashion. The taste might have been a factor. While Master Chef Mario Batali claims swan meat is “delicious—deep red, lean, lightly gamey, moist, and succulent”—others have called it “gristly” and “mud flavoured.” If you happen to come across swan at your neighbourhood butcher (most unlikely), and wish to give it a try, here is a link to a fourteenth-century recipe for roasted swan with chaudon (a.k.a. giblet) sauce. Roasted swan.

Royal mute swans came to Ottawa in 1967, Canada’s centennial year, as a gift to the nation’s capital from Queen Elizabeth who also doubles as Seigneur of Swans. It was not the first time that Canada has received Royal swans. In 1912, George V gave a pair of Royal mute swans from his flock at Hampton Court to St Thomas, Ontario. The birds were settled on Pinafore Lake. They didn’t flourish. More mute swans were imported in the early 1950s from the United States, Scotland and from Stratford, Ontario which itself received mute swans in 1918 from Mr J. C. Garden. Today, St Thomas’s imported mute swans have been replaced by native trumpeter swans (Cygnus buccinator) in a programme to re-introduce the breed into southern Ontario. King Edward VIII also presented two Royal swans to North Sydney, Nova Scotia in 1936.

The gift of swans has not always been unidirectional. In 1951, the Federal and British Columbian governments gave six Canadian trumpeter swans to the then Princess Elizabeth. The swans were put into the care of the Severn Wild Fowl Trust.

Ottawa’s Royal mute swans arrived in the city in late May 1967, the culmination of careful planning on the part of Buckingham Place, Rideau Hall, the City of Ottawa, the Federal government and two airlines. Arriving by airplane at Uplands Airport, the birds, which had been specially selected by the Keeper of the Queen’s Swans from the Thames River, were placed into precautionary quarantine. At 4pm on 28 June 1967, following speeches by the Governor General and Ottawa’s Mayor Donald Reid in front of hundreds of guests, eight Royal swans were released into the Rideau River just above the Rideau Falls on the grounds of the old city hall (now the Federal government’s John G. Diefenbaker building) on Green Island. Two other pairs of swans remained at the “swan house” at the City’s Leitrum tree nursery for breeding purposes. Noting that swans mated for life, Governor General Roland Mitchener joked that in light of the prospective liberalization of Canada’s divorce laws, the birds might have to face “some previously unknown temptations.” The birds’ ability to fly was disabled to stop them from straying, physically if not maritially.

The swans were in place on July 1, 1967, Canada’s centennial day, ready for the Queen’s inspection when she and Prince Philip arrived at City Hall on their Royal Tour of Canada. The Ottawa Journal wrote that the swans, paddling from shore to shore on the Rideau River “enhanced a scene of calm and beauty.” Their “regal beauty complemented every natural and man-made fixture in sight.”

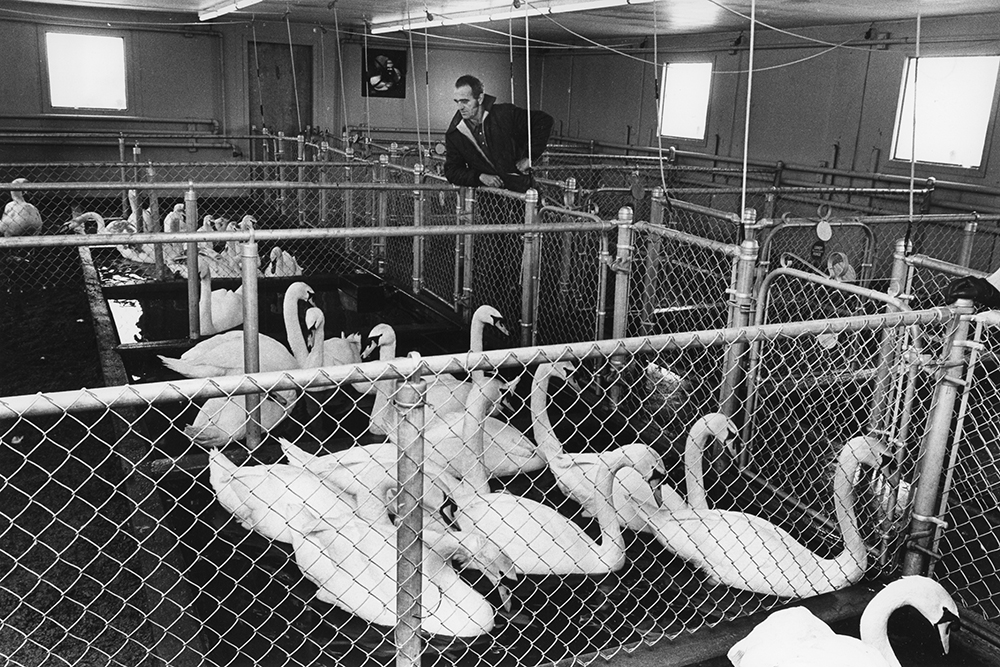

The graceful, long-necked, white birds were an instant sensation as they cruised the Rideau River, stopping along the way to eat aquatic vegetation, as well as the odd tadpole, snail or insect. Couples quickly established territories along the river bank. When the cold weather came in late October, the birds were moved to their winter quarters at Ottawa’s tree nursery in Leitrim. There, they were housed in less than regal surroundings in a greenhouse made of heavy-duty plastic and chicken wire with an earthen floor and an artificial pond. In 1971, a wooden swan house was built with pens for each couple and an outside exercise yard. The birds were cared by Ottawa’s first swanmaster, Mr. Gerry Strik, who was also the manager of the Leitrim tree nursery. Mr. Strik had previous experience caring for swans in his native Holland. That same year, the Royal swans made their theatrical debut, appearing in the National Arts Centre production of The Marriage of Figaro. Swanmaster Strik, dressed appropriately, was in the wings in case the birds misbehaved. Appearing on stage for the entire final act, the swans performed admirably.

Swanmaster-Gerry Strik with Royal swans at their indoor winter quarters, March 9, 1978, City of Ottawa Archives/CA025513/Peter Earle.

Swanmaster-Gerry Strik with Royal swans at their indoor winter quarters, March 9, 1978, City of Ottawa Archives/CA025513/Peter Earle.

There were, however, some reservations about the new Rideau River inhabitants. One City Councillor worried that the honking of swans might be a violation of the city’s anti-noise by-law. His concern was allayed by Margaret Farr, the deputy commissioner of Ottawa’s Parks and Recreation Department. She said the birds were relatively quiet, though they sometimes “grunted like pigs.” Another councillor worried about the swans’ reproductive capacity. As mute swans lay clutches of up to five eggs, he figured that within five years Ottawa could be the proud owner of 72 pairs of birds. Mute swans are also long-lived, with a lifespan of thirty years or more.

This later concern turned out to be prophetic. Quickly, the swan population rose despite losses due to disease and misfortune. Sadly, there were also a number of cases of cruelty towards the birds and their nestlings. Eggs were also destroyed. One adult bird was shot while another was clubbed to death with a baseball bat. Yet another was found dead with a fish hook in its mouth. Two disappeared without a trace, presumably taken by somebody with a taste for swan flesh. Despite such losses, by the early 1970s, there were forty birds, and the City was looking around for solutions to limit their numbers; forty birds was deemed to be the maximum the Rideau River could accommodate. This gave rise to an interesting problem. Would it be a case of lèse majesté to dispose of some swans? After consulting the British High Commissioner and the Governor General, both of whom didn’t have an answer, the question was resolved by the Lord Chamberlain of England. His answer was there was no problem if the City gave swans away to good homes. However, such birds could not be designated as royal gifts. The Queen herself suggested that only two eggs be left in each nest.

Despite concerns about swan numbers, Ottawa acquired a pair of black Australian swans (Cygnus atratus) in July 1974. The source of the birds and the rationale for acquiring them are a bit murky. According to the City of Ottawa’s website, the birds came from the Montreal Zoo in an exchange. However, contemporary newspaper reports say they came to Ottawa in a trade with Wallaceburg, Ontario. These birds do not carry the “Royal” designation as they were not a gift from the Crown.

By the early 1990s, City Council, looking for cutbacks in an age of austerity, considered eliminating the city’s swans, and in the process saving some $37,500 or more per year in winter maintenance, a cost that had increased ten-fold since 1967 due partly to inflation and partly to the increase in the swan population. One city official jokingly suggested that Ottawa host a big barbecue. After receiving hundreds of letters in support of the birds, City Council instead agreed to reduce their numbers to save money. A few years later, City Council again tried to eliminate the swans. Jim Watson, a city alderman at the time, called the swans “a frill.” Fortunately for swan lovers, the high-tech. company Cognos stepped up in early 1996, providing $26,300 to cover that year the maintenance costs of twenty-two white Royal swans and 5 black Australian swans. The company continued to pay for the swans’ maintenance until 2007. The following year, IBM, which had taken over Cognos, stepped in and contributed $300,000 in a lump sum for the maintenance of the birds.

About the same time, concerns were raised about deteriorating conditions at the swan house at the Leitrim Tree Sanctuary. Although called “Swantanamo Bay” by some wags after the notorious U.S. military and prison camp in Cuba, the Ottawa Humane Society said the unsightly facility did not pose a “significant health or safety risk” to the birds. With IBM funds devoted to the annual maintenance of the birds, the city looked into building replacement quarters for the birds. With the estimated cost approaching $500,000 (!), the idea of building a new swan house was quickly shelved. When the Leitrim facility finally closed in 2015, the birds were sent to winter quarters at Parc Safari in Hemingford, Quebec under a two-year arrangement costing roughly $30,000 per year.

Typically, the swans are released back into the Rideau River in late May. However, in 2017, the swans, now a much reduced group of eight, six Royal mute swans and two black Australian swans, were released in late June owing to high water conditions prevailing earlier in the spring. Mayor Jim Watson and Councillor Diane Deans officiated at the event held at Brantwood Park at the end of Clegg Street.

How many more years this annual event will take place remains an open question. While the Royal mute swans are attractive and have many admirers, they are considered an invasive species in North America that competes with native trumpeter swans. Although Ottawa’s swans on the Rideau are pinioned, a requirement of the Federal Wildlife Act in order to stop them flying away and going feral, pinioning is a controversial procedure. Liken to the cropping of the tail and ears of certain breeds of dogs or removing the claws of cats, pinioning involves the surgical removal of the pinion joint of the wing. This procedure permanently stops a bird’s flight feathers from growing thereby disabling its ability to fly. It’s typically done without anesthesia, and is banned in some countries under animal protection laws. While Ottawa’s Royal swans made it through 2017, Canada’s sesquicentennial year (and the 50th anniversary of the Queen’s gift), their future is not bright unless another sponsor steps forward.

Update: In a 20-2 decision, Ottawa City Council agreed in June 2019 to give the remaining four royal mute swans and one Australian black swan to Parc Safari in Hemingford. Apparently, their numbers had been affected by predation by coyotes. The aging birds were also being stressed by moving back and forward from Hemingford to Ottawa.

Sources:

Answer Fella, 2011. “Why Not Eat a (Black) Swan on Oscar Night?” Esquire, 23 February, http://www.esquire.com/food-drink/food/a9453/black-swan-recipe-0311/.

Barger, Brittani, 2016, “Does the Queen really own all the swans?” Royal Central, http://royalcentral.co.uk/blogs/does-the-queen-really-own-all-the-swans-57621.

CBC, News, 2008. “IBM bails out Ottawa’s royal swans,” 20 November.

Cornell, Lab of Ornithology (The), 2017. “Mute Swan,” https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Mute_Swan/lifehistory.

Duhaime.org. 2007. Crazy Laws—English Style (1482-1541), http://www.duhaime.org/LawFun/LawArticle-359/Crazy-Laws–English-Style-1482-1541.aspx.

Field, Mrs Marshall (Dolly), 1951. History of the St. Thomas Filed Naturalist Club, 1950-67), http://inmagic.elgin-county.on.ca/ElginImages/archives/ImagesArchive/pdfs/ECVF_B99_F30.pdf.

Globe and Mail, The, 1951. “To Send Royal Pair Gift Of 6 Swans,” 10 November.

————————–, 1955. “The Swans of St. Thomas,” 10 December.

————————–, 1992. “Squaking Squelches Notion Of Swan Song,” 23 April.

————————-, 1996. “With Her Swans Looked After,” 10 January.

————————-, 1996. “Cognos Picking Up Tab For Swans, $26,300 per year.” 10 October.

Gode Cookery Presents, 2017. “For to dihyte a swan,” Medieval recipes, http://www.godecookery.com/mtrans/mtrans52.html.

Ottawa, City of, 2016. “Royal swans to be released along the Rideau River,” 20 May.

——————, 2016. “Royal swans make annual return to the Rideau River,” 24 May.

——————, 2017. “Royal Swan FAQs,” http://ottawa.ca/en/residents/animals-and-pets/other-animals#royal-swan-faqs.

Ottawa Humane Society, 2013. Royal Swan FAQs, https://web.archive.org/web/20091203010345 /http://www.ottawahumane.ca/protection/swan.cfm

Ottawa, Journal (The), 1967.”Swans Fly Atlantic – By Plane,” 31 May.

—————————, 1967. “Royal Swan Song Worries Council,” 20 June.

—————————, 1967. “Mitchener To Present,” 21 June.

—————————, 1967. “Letter to Citizens of Ottawa from Mayor Don Reid,” 27 June.

—————————, 1967. “City’s Royal Swans ‘Launched,’” 29 June.

—————————, 1967. “Those Royal Swans,” 8 July.

—————————, 1967. “The Royal Swans,” 15 July.

—————————, 1967. “Swans To Winter In Leitrim,” 21 October.

—————————, 1971. “Royal Swan Upkeep Set At $3,500 in 1971.” 20 May.

—————————, 1971. “Royal Swans Have Part In NAC Opera,” 6 July.

—————————, 1971. “Royal Swan Clubbed to Death,” 21 October.

—————————, 1972. “Yes—Swans Can Be Given Away,” 20 March.

—————————, 1973. “Royal Swans….” 24 March.

—————————, 1973. “Queen Finds Answer To City’s Swan Dilemma,” 2 August.

—————————, 1978. “It’s Your Royal Flock,” 19 May.

—————————, 1979. “Swan Song,” 13 September.

—————————, 1979. “Attempt To Cut Numbers by 8 To 20 Defeated.” 13 October.

Ottawa Sun, 2016. “City Still Trying To Find A Permanent Winter Facility,” 24 November.

Queen’s Swan Marker, 2012. Royal Swan Upping, The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Edition, http://www.royalswan.co.uk/sources/indexPop.htm.

Shaw, Hank, 2015. On Eating Swans, http://honest-food.net/on-eating-swans/.

Stratford, City of, 2007. “The Swans of Stratford,” http://www.visitstratford.ca/uploads/brochure2007c.pdf.

St. Thomas Times Journal, 2013. “Nature takes toll on St. Thomas swan cygnets,” 21 August.

Toronto, City of, 2011, “Birds of Toronto,” https://www1.toronto.ca/City%20Of%20Toronto/City%20Planning/Environment/Files/pdf/B/Biodiversity_Birds_of_TO_dec9.pdf.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Ottawa City Hall Fire

31 March 1931

Ottawa’s first city hall was a wooden structure built close to Elgin Street in 1848 by Nicholas Sparks. It had originally been a market. But when the market failed the following year, eclipsed by the more popular Byward Market in Lower Town, Sparks donated the building to Bytown (later known as Ottawa) as the town’s city hall. For close to thirty years it served in this capacity, for a time also doubling as the community’s fire hall. Pressed for space, the city’s municipal offices moved into a bespoke building constructed in 1876 on an adjacent lot located on Elgin Street between Queen and Albert Streets—roughly where the National Arts Centre is today. The four-storey, stone building was designed by the architects Henry H. Horsey of Ottawa and Matthew Sheard of Toronto in the French Empire style, a mode of architecture which was much admired during the late nineteenth century. The City Hall, built for $85,000, was apparently considered by many at the time as “the finest example of municipal architecture.”

But by the 1920s, the City had once again outgrown its now aging city hall. In 1927, the Liberal government of Mackenzie King came to an agreement with the City over the eventual expropriation of the building, along with the Police and Central (No. 8) Fire Station buildings located behind it, the Russell Hotel, the Russell Theatre, and the Post Office, in a grand plan to beautify Ottawa through the creation of Confederation Park, the construction of a War Memorial to honour Canadian service personnel who died during the Great War, and the widening of Elgin Street. Although the Russell Block was expropriated in 1927 by the federal government, and the City itself took over several buildings including Knox Presbyterian Church for the widening of Elgin Street, plans for the park stalled with the coming of the Great Depression in 1929 and the election of a parsimonious Conservative government under R. B. Bennett in 1930.

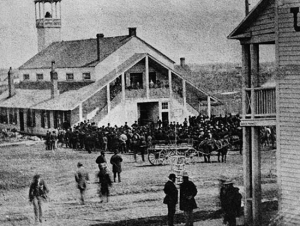

Ottawa City Hall, 1877-1931, Elgin Street

Ottawa City Hall, 1877-1931, Elgin Street

Library and Archives Canada, Mikkan 3325359.The municipal offices were still located in their Elgin Street premises when a fire gutted the building. During the evening of 31 March 1931, two men passing by the nearby Post Office spotted smoke and flames coming from the top corner of the north-east side of the City Hall. The passers-by rushed to the No. 8 Fire Station. The fireman on duty initially thought the men were pulling an April Fool’s prank on him. But after stepping outside, he quickly call out the fire fighters. The first alarm sounded at 9.25 pm with a second alarm sounding a few minutes later, calling in fire fighters from across the city.

Firemen initially entered the east tower of the Hall that led to the office of Vincent Courtemanche, the City’s paymaster. Courtemanche was working late that night preparing workers’ pay sheets. Hearing the hubbub outside his office, he initially thought a prisoner had escaped from the police lock-up. On finding that the City Hall was ablaze, he rushed upstairs to warn Finance Commissioner Gordon who was also working late. The two men fled the building after retrieving $8,000 in cash and $20,000 in cheques. Gordon also managed to save a cheque-writing machine newly purchased for $1,000. Reportedly, a one-ton safe was dragged be two policemen and two volunteers from the Treasury Department to the offices of Hugh Carson Ltd, the maker of leather goods at 72 Albert Street, for safe-keeping.

The fire started in the office of T. B. Rankin, the accountant of the City’s engineering department located on the northeastern corner of the top floor. Firemen were able to bring two hoses to Rankin’s office, but the blaze had already spread through the false ceiling and could not be contained. It quickly swept through the neighbouring offices of the Waterworks department and the draughting room of the Works department. The office of the building inspector was also consumed by the flames.

Downstairs, a meeting of the Central Council of Social Agencies was underway in the Board of Control boardroom. Controller J.W. York, who was attending the meeting, immediately called Mayor Allen and other councilmen. After saving the records of the Board of Control, Controllers Gelbert and York, along with a Journal newsman, went upstairs to salvage records from the Waterworks and Works departments. The three men had a narrow escape when a wall collapsed under the pressure of the water from the firemen’s hoses on the other side of the wall of the room they were in. They were forced to drop everything and flee to safety. Following his arrival on scene, Mayor Allen took charge of saving documents. Men frantically slid steel filing cabinets filled with important municipal records down the building’s marble staircase to get them outdoors.

The fire was intense. Seven firemen were injured when the top floor on which they were working collapsed without warning, dropping them more than fifty feet into the basement. Some were pinned for more than an hour under smoldering debris while their colleagues desperately dug to free them. Rev. Father J. L. Bergeron of Ottawa University smashed the glass of a basement window and crawled in to administer last rites to the pinned men. Fortunately, the sacrament was not needed. All the trapped firemen were rescued by their colleagues who “worked like Trojans” to get them out. None of their injuries proved to be life-threatening. But it was a narrow escape. Later in the Water Street hospital, one of the injured admitted that they had received “a real break,” though he phlegmatically added that it was “all part of the game.” Ironically, just two weeks before the fire, the City’s Board of Control had received a report indicating that the Works department vault was supported by only one girder that placed it at risk in the event of a fire. The Board of Control had discussed the building of a more secure vault at the rear of the City Hall at a cost of $70,000 dollars but no decision had been taken.

One hundred and twenty-five firemen from across the city were called out to fight the blaze. To help increase the water pressure, an old steam engine from No. 7 Fire Station was brought into action. A detachment of the RCMP was also called in to help Ottawa police keep more than 20,000 on-lookers from hindering the work of the fire brigade, and to keep them a safe distance from falling debris and flying embers. Just after midnight, tons of masonry from the stone tower at the south-west corner collapsed sending the vault in the Assessment department through the floor through the Health department, the Board of Control room, and the Central Canada Exhibition offices.

Fortunately, the fire didn’t reach the ground floor office of N. H. Lett, the City Clerk. His precious records of elections, plebiscites, and vital statistics survived the fire. Paintings and other valuables were also rescued, including portraits of former mayors and pictures of the King and Queen. Small busts of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir Wilfrid Laurier were later found in the Mayor’s Office intact albeit somewhat water damaged. The stock of a little cigar stall that stood at the front entrance was also saved. Estimated losses associated with the fire were placed at more than $200,000. Total insurance coverage amounted to only $91,200 for the building and $10,000 for contents. The cause of the blaze was never ascertained.

Even before the flames were extinguished, work began on finding temporary accommodations for civic workers. The City obtained permission from the federal Department of Public Works to use two floors of the Regal building on O’Connor Street that had just been vacated by the Department of Labour for the Confederation Building on Wellington Street. But efforts to move furniture into the building and set up a switch board were quickly halted when the owner of the building objected. As the City began seeking other alternatives, Mayor Allen and other City Controllers worked out of Controller York’s law office. Some city services set up temporary offices at the Coliseum on Bank Street, others on Bank Street and in LeBreton Flats. Three days after the fire, the City found satisfactory accommodations in the Transportation Building on Rideau Street. (The Transportation Building, built in 1916, stands at the corner of Rideau Street and Sussex Drive and is now incorporated into the Rideau Centre.) Previously the home of the Auditor General, the City rented the top three floors at a cost of $22,500 per year, equivalent to $1.50 per square foot. Most civic departments eventually moved here.

Despite the confusion in the days immediately following the fire, most municipal services were unaffected. City staff were paid on time that week by City Paymaster Courtemanche using temporary facilities at the Police Station. Only Ottawa’s sweethearts were disappointed. City Clerk Lett halted the issuance of marriage licences for twenty-four hours owing to his stock of blank certificates being waterlogged.

The Mayor and Council quickly initiated talks with the Bennett government over the future of the gutted City Hall building. The Mayor proposed that the federal government purchase the land for $2 million consistent with the 1927 plan to establish Confederation Park on the site. But Bennett’s government demurred. The price tag was simply too great. Discussions then focused on whether to restore the damaged building, rebuilt on the same site, or seek an alternate site for a new City Hall. The Ottawa Journal was of the view that restoring the damaged building was a waste of money. It opined that the fire had shown the “folly and danger” of its “ugly, wooden towers which architects of a generation or two ago seemingly insisted upon.” It added “The truth is that a lot of mid-Victorian architecture was as slovenly as the dress of a lot of mid-Victorian women – and about as useless.” What had been viewed as the epitome of fine municipal architecture fifty years earlier was now thoroughly out of fashion and a fire hazard to boot.

It took some months for Council to make its decision to demolish the gutted building, contracting with D. E. Mackenzie to pull it down for $1,800 in October 1931. The City retained ownership over the cornerstone, and all plaques and memorials. The decision to demolish the old building was not unanimous. Mayor Allen and Controller Gelbert favoured erecting a temporary roof and using the basement as the civic employment office. A number of potential locations were discussed for a new home for the City Hall, including sites on Wellington Street next to St. Andrew’s Church between Kent and Lyon Streets, the west side of Elgin Street between Queen and Albert Streets, as well as rebuilding on the existing site. But with a price tag of $600,000, and in light of the considerable expenditures the City had recently incurred on sewer upgrades following the sewer explosions earlier that year, and the cost of building a water purification system, city fathers believed it prudent to wait until better economic conditions prevailed before re-building. It wouldn’t be until the 1950s that Ottawa moved into new accommodations constructed on Green Island. The new City Hall building was officially opened by Princess Margaret in early August 1958. The structure, now known as the John G. Diefenbaker building, is currently occupied by Global Affairs Canada.

With the creation of a single-tier city structure, and the merger of surrounding communities into the City of Ottawa in 2001, city government moved to the offices of the defunct Regional Municipality of Ottawa-Carleton at the corner of Laurier Avenue and Elgin Street, facing Confederation Park. Interestingly, this is roughly the site proposed for Ottawa’s City Hall by the Ottawa Citizen newspaper in 1931.

Sources:

Citizen (The), 1931.”5 Firemen In Narrow Escape, Property Loss $15,000,” 1 April.

—————-, 1931. “Ask Government If It Wants City Hall Razed,” 1 April.

—————-, 1931. “City Hall Built in 1875-76, Renovated During 1910-11,” 1 April.

—————-, 1931. ‘For A New City Hall,” 2 April.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1931. “Mayor and Board See Premier About City Hall,” 1 April.

————————————, 1931. “How Ottawa City Hall Looks Today After Night Blaze of Six Hours,” 1 April.

————————————, 1931. “Three firemen Say They Had A Lucky Break,” 1 April.

————————————, 1931. “Cause of Blaze – A Mystery To Chief Lemieux,” 1 April.

————————————, 1931. “Thrilling Scenes And Brave Rescues Mark City Hall Fire,” 1 April.

————————————, 1931. “Fourth Floor Collapses Trapping Seven Men Under Debris In Cellar,” 1 April.

———————————–, 1931. “Board in Special Meeting Decides on New Offices,” 1 April.

———————————-, 1931. “Ask Government $2,000,000 For City Hall Site,” 2 April.

———————————-, 1931. “City Business Carried on Despite Difficulties Faced Securing Temporary Offices,” 2 April.

———————————-, 1931. “Why Waste $150,000 On An Inadequate Building,” 2 April.

———————————-, 1931. “Wretched Wooden Towers,” 2 April.

———————————-, 1931. “Will Consider Construction New City Hall on Present or Some Other Location,” 3 April.

———————————-, 1931. “New Quarters For City Staff Are Arranged,” 4 April.

———————————-, 1931. “Will Demolish The Fire Ruins Of City Hall,” 12 August.”

———————————-, 1931. “Another Site For New City Hall Offered,” 18 September.

———————————-, 1931. “Decide To Tear Down City Hall Ruins At Once,” 3 October.

———————————-, 1931. “Still Unable Start Tearing Down Building,” 6 October.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.