Women on Ice: Ottawa’s Own

It was just coincidental, though perhaps entirely appropriate, that the presentation on March 23, 2024, at the Main branch of the Ottawa Public Library titled “Ottawa Women on Ice” took place against the backdrop of the World Figure Skating Championships in Montreal and a game between Ottawa and Toronto in the newly-formed Professional Women’s hockey League. James Powell, the speaker that afternoon, told an enthusiastic audience of 44 about Ottawa’s lengthy and often glorious history in women’s hockey and the achievements of two Ottawa women in figure skating—Barbara Ann Scott and Elizabeth Manley. James is a frequent speaker at HSO and community events; runs the blog “Today in Ottawa’s History” and was awarded the Historical Society of Ottawa’s Story Teller award in 2023 for his fine work in telling Ottawa’s history.

Few probably realize that women’s hockey started in Ottawa when Isobel Stanley, the daughter of Lord Stanley, Canada’s Governor General from 1888-1893, strapped on a pair of skates in 1889 and stick-handled around other Rideau Hall women in the first ever women’s hockey game in an outdoor rink at Government House. That same year, Isobel Stanley and other ladies from Rideau Hall triumphed over a team from the Rideau Rink in the first ever women’s hockey game covered by the press. With a vice-regal stamp of respectability helping to alleviate concerns about the appropriateness of women playing hockey, women’s hockey teams multiplied in the Ottawa-Hull area and throughout the Ottawa Valley, this included the “Alphas” of New Edinburgh, the Rideau Rink Ladies, the Vestas of Hull, and the Cliffside Ladies, also known as the “Busy Bees,” who claimed the first city championship when they defeated the Sandy Hill Ladies in 1908. Away games by Ottawa teams to play teams in Smiths Falls and Cornwall were chaperoned to keep the young ladies in line. Long skirts and tam-o-shanters were the uniforms of the day.

Women’s hockey received a major boost with the outbreak of World War I. With the men away, scarce rink time opened up for women. As well, rink owners looked for new ways to rent out the ice and fill seats. In Montreal, a women’s hockey league brought in thousands of fans attracted by the high calibre of the game. Many also came to see the Cornwall Victorias, led by their superstar Albertine Lapensée, also known as the “Miracle Maid” and “Étoile des étoiles”, and the Ottawa Alerts, the formidable team from the Capital. Lapensée was likely the first professional female hockey player.

The origins of the Ottawa Alerts are obscure but the team, captained by Edith Anderson burst onto the scene in 1916. Their most fierce local rivals were the Westboro Pats led by Tena Turner. The two teams fought for the city championship in 1917 with the Alerts prevailing in a two-game, total goal series. The Alerts then defeated the Westerns, Montreal’s hockey champions, to win the Dey Cup.

The Ottawa Alerts joined the Ladies’ Ontario Hockey Association (LOHA) in 1922 when the league formed, bringing together fifteen teams from across the province. Behind their star player, the all-round athlete Shirley Moulds, the team won two consecutive championships in 1923 and 1924. The Alerts went into decline when Moulds moved to the Ottawa Rowing Club as the team’s captain. The “Scullers” defeated the Alerts to take the city championship in 1927, and subsequently won the provincial title, defeating the Toronto Pats.

The Great Depression was the death knell for women’s hockey in Ottawa and in Canada more generally. Both the Alerts and the Scullers disappeared into history as did the LOHA and the Dominion Women’s Amateur Hockey Association, the latter founded in 1933. By the onset of World War II, organized women’s hockey was no more. However, before the end came, the 1930s saw the emergence of the most powerful women’s hockey team of the era—the Preston Rivulettes. During its short career, the team lost only two out of 350 games.

Women’s hockey didn’t re-emerge as a significant sport until the 1970s. However, leading the way in the post-war era was ten-year old Dee Dee Hamilton who stepped into the breach in 1956 when the goalie on her brother’s team, the St. Pat’s, couldn’t play in a game hosted by Ottawa’s Cradle Hockey League. So good was Dee Dee that she played in the 1957 All-Star Game. For two years, she was the only girl amidst 800 boys in the league.

With the establishment of a new professional women’s hockey league at the beginning of 2024 with a team in Ottawa, it is possible that the old “Alerts” name may be revived. In the lead-up to the formation of the league, a number of trademarks were registered for potential names of its clubs. In addition to such monikers as the Toronto Torch and the Montreal Echo was the Ottawa Alert.

Credit: Frank Royal / National Film Board of Canada / Library and Archives Canada / PA-112691.Switching to figure skating, James traced the career of Canada’s sweetheart, Barbara Ann Scott, from winning the Canadian Junior Figure Skating crown in 1940 to taking the gold medal at the 1948 Winter Olympics held in St. Moritz, France. But it didn’t come easily for Scott. Her success required long hours of practice and hard work, training at the Minto Skating Club, the skating club founded by Lord and Lady Minto in 1903. James showed a short film of her performance at St Moritz which displayed her grace and form as a gold-medal figure skater.

Credit: Frank Royal / National Film Board of Canada / Library and Archives Canada / PA-112691.Switching to figure skating, James traced the career of Canada’s sweetheart, Barbara Ann Scott, from winning the Canadian Junior Figure Skating crown in 1940 to taking the gold medal at the 1948 Winter Olympics held in St. Moritz, France. But it didn’t come easily for Scott. Her success required long hours of practice and hard work, training at the Minto Skating Club, the skating club founded by Lord and Lady Minto in 1903. James showed a short film of her performance at St Moritz which displayed her grace and form as a gold-medal figure skater.

Returning to Ottawa as a national hero after the Olympics, some 70,000 fans met her train at Union Station, where she was personally greeted by Prime Minister Mackenzie King and Ottawa Mayor Stanley Lewis. Schoolchildren were given a half-day holiday. In honour of her victory, Ottawa gave Scott a car with the licence plate 48-U-1. She then started her professional career, ousting Sonja Henning, her arch rival, from the Hollywood Ice Review. In 1950, the most desired Christmas gift was a Barbara Ann Scott doll, complete with white figure skates, costing a steep $5.95.

Scott retired from skating in 1955 when she married Tom King. In 1991, she was appointed to the Order of Canada. Scott passed away in 2012 in Florida at age 84. She bequeathed her sports memorabilia to the City of Ottawa.

James ended his presentation with the career of another daughter of Ottawa, Elizabeth Manley, who won the silver medal at the 1988 Olympics in Calgary. Like Scott forty years earlier, it took years of grit and determination to achieve perfection—and that was what she achieved in her long program in Calgary. Although she came first in that section of the competition, she lost overall by a hair to East Germany’s, Katerina Witt. At the end of a short video of her long program, people in the library auditorium broke out into applause, indicative of the power of Manley’s performance thirty-four years ago. Manley was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1988, and, following her skating career, has devoted considerable time to charity.

In the usual question and answer section that followed, three descendants of Shirley Moulds, the Ottawa Alerts’ star player, identified themselves in the audience. They indicated Moulds had been a very private person who had not talked about her hockey career. Her niece said that it was only after Shirley’s death that she became aware of her prowess as a hockey player. The only thing she knew was that Aunt Shirley was a great bowler! Shirley Moulds’ great-nephew was instrumental in Moulds being named to Ottawa’s Sports Hall of Fame in 2010.

Tea with Adrienne Clarkson

In January 2024, Andrea Bissonnette, Ben Weiss and myself had an extraordinary experience—the opportunity to sit down with Madame Adrienne Clarkson at the Château Laurier Hotel to have tea and chat about her past and Ottawa history more generally. For those who might need a reminder, after a stellar career as a journalist, Madame Clarkson was Canada’s governor general from 1999 to 2005, and the Historical Society of Ottawa’s patron.

The story began in the spring of 2023 when Andrea contacted the Historical Society of Ottawa regarding an old family photograph album that had originally belonged to her grandmother, Marie Albina Guilbeault. Andrea had inherited it following the passing of her mother, and offered the photos to the Society.

Although the Society no longer maintains a photo archive, we agreed to go through the album, scan photographs of interest, and then send the collection to the City of Ottawa Archives. Among Andrea’s fascinating photos was a picture of her great-grandfather, Arthur Guilbeault, who was a mayor of Eastview (Vanier) in the 1920s, and another of Zoë Laurier, the wife of Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

It took us some months to go through the album in detail. In January, Ben Weiss read a number of newspaper clippings, snipped by Andrea’s grandmother, about her son, Andrew (André) Bissonnette, who was Andrea’s father. Representing the Ottawa Technical Institute, Andrew had won third prize in a Rotary Club public-speaking contest held on April 1, 1955 at the Château Laurier Hotel. Perusing the articles more closely, Ben recognized the name of the second-place winner—16-year-old Adrienne Poy, the young immigrant girl from Hong Kong who was to become Canada’s 26 th governor general.

Ben contacted Madame Clarkson’s office and offered to send the newspaper clippings to her as a gift. Instead, Madame Clarkson graciously volunteered to receive them in person as she was soon to be in Ottawa to give an address on leadership at Carleton University.

After meeting at the City of Ottawa Archives where Andrea officially donated her grandmother’s photographs, Andrea, Ben and I trooped down to the Château Laurier, expecting a brief meeting with Madame Clarkson. Instead, she spoke with us for more than an hour. It seemed like she would have happily chatted longer had it not been for another appointment (which turned out to be with none other than Randy Boswell, the well-known journalist, professor and Society member!).

Madame Clarkson was delighted to receive the clippings and recalled the Rotary contest in detail. In the lead-up to the event, she had practised under the direction of her English teacher, Mr. Mann. She entered the Rotary inter-school contest by winning a similar public-speaking event at her school, Lisgar Collegiate. Madame Clarkson said that Mr. Mann had had a profound influence on her, giving her skills that had served her well through her life.

The topic of her young Adrienne Poy’s twelve-minute presentation was “The Problem of China.” She also had to speak extemporaneously for two minutes on the postal system. She clearly impressed the judges and the reporters covering the event. Indeed, her speech garnered more press coverage that that of the first-place winner, Tony Reynolds from Glebe Collegiate, who spoke on “Moral Rearmament.” Madame Clarkson recalled that “moral rearmament” had been a popular, neo-fascist philosophy during the 1950s. (A 1967 article that appeared in The Harvard Crimson called the movement simplistic, anti-intellectual, emotional, and irrational.) Madame Clarkson said that her second-place finish had come as a disappointment; she had hoped to take first place. Indeed, there had been a general feeling that she had performed better than Reynolds but lost owing to her gender. In the 1950s, women did not come first.

Responding to a question from Andrea, Madame Clarkson admitted that while she knew Andrea’s father, Andrew Bissonnette, she did not know him well. She gave Andrea a hug when Andrea revealed that she had never met her father as he had tragically died while her mother had been three months pregnant with her. To talk to somebody who had known her father, even a little bit, was very special.

Madame Clarkson went on to speak about her early life in Ottawa after her family arrived as refugees from Hong Kong in 1942. Her first recollection was falling off the steps of a streetcar. Landing in a snowbank, three-year old Adrienne Poy was fortunately uninjured. She also recalled that her mother didn’t know how to cook when they first arrived in the city. Francophone neighbours taught her how to prepare Western food. Later, Mrs. Poy learnt how to cook Chinese cuisine at a Chinese restaurant. Subsequently, the Poy family ate Chinese food on weekdays and Western food on weekends.

She also described the social and religious divides in Ottawa at the time—English versus French, Irish versus Francophones in Lowertown, and Catholics versus Protestants. One thing she did not experience was anti-Chinese bias, possibly because there were so few Chinese in Ottawa owing to the 1923 exclusion law that barred most Chinese from emigrating to Canada until 1947. But, even within Ottawa’s small Chinese community—just two Chinese restaurants—there was a divide between those who had owned land back in China and those with a water, or fishing background. Her mother would not allow young Adrienne to bring home Chinese children with a fishing heritage.

One thing that was strong in the Poy household was their attachment to the Anglican Church. Madame Clarkson’s parents had been married in Hong Kong by Bishop Ronald Hall, who became famous for the ordination of Florence Li, the Anglican Church’s first woman priest, in 1944. After living in an apartment on Sussex Avenue, the Poy family later moved to Laurier Avenue west to be closer to Christ Church Cathedral where her parents were active members.

When asked about why her family remained in Canada after the war, Madame Clarkson said that her parents had considered going back to Hong Kong. Indeed, many Hong Kong friends were expecting and hoping that they would return. However, her father, William Poy, was concerned about the future of the British colony given the rise of Mao Zedong, fearing that Hong Kong could not last more than two years after Mao’s takeover of mainland China. While his fears later proved to be mistaken, the family stayed in Ottawa.

Noting that her upcoming birthday fell on the Chinese New Year, Ben asked Madame Clarkson if that had any significance for her. She laughed, saying that it did for her mother. Mrs. Poy spent the last three weeks of her pregnancy in bed in the hope that her child would be born a “rabbit” instead of a “tiger.” Failing in that endeavour, she despaired that young Adrienne’s character would be too forceful, making it difficult for her to find a husband.

Madame Clarkson also talked about senior government positions. She said she had turned down an offer to become a senator as she felt that she didn’t have the temperament for the job. While she could do committee work, it wasn’t her preferred type of activity. The role of governor general was more in keeping with her leadership skills. One position she has particularly enjoyed is being Colonel-in-Chief of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, a role she has had since 2007. Madame Clarkson noted that she was only the third Colonel-in-Chief since the formation of the regiment in 1914, and is proud to be the first Canadian.

With her assistant indicating that it was 3:30pm, and time for her next appointment, Andrea, Ben and I gave our thanks and said our goodbyes. Before going, Ben gave Madame Clarkson a copy of Dorothy Phillips’ book on the Duke and Dutchess of Devonshire, Victor and Evie, British Aristocrats in Wartime Rideau Hall as well as Bill Galbraith’s work on Lord Tweedsmuir titled John Buchan: Model Governor General. He also gave honorary membership certificates to both Madame Clarkson and Andrea. We hope that both are able to join us for future events.

Dorothy Phillips: Victor and Evie

Our meeting on April 28, 2021, was as much a romance story as it was a history lesson. HSO member Dorothy Phillips has researched the life of the Duke of Devonshire, Victor Cavendish and his wife, Lady Evelyn Petty-Fitzmaurice, which the duke affectionately called “Evie”. In 2017, Dorothy assembled her extensive research into a book, Victor and Evie: British Aristocrats in Wartime Rideau Hall.

Unlike many of Canada’s governors general who accepted their posting as just a stepping stone to better political opportunities in the UK, or to a future diplomatic assignment in a warmer part of British Empire, Victor Cavendish loved the time they spent in Ottawa. The couple contributed much to the city’s life. Evie was well known as a gracious host, holding twice-weekly dinners for government officials, and Saturday afternoon skating parties for the common folk. Victor and Evie spent their summers at a cottage at Blue Sea Lake, about 100 km north of Ottawa. Their eldest daughter Maud was the first child of a governor general to be married in Ottawa.

Evie was already familiar with Rideau Hall when her husband became governor general in 1916. She had lived in the same Governors’ Mansion as a teenager when her father, The Marquess of Lansdowne was Canada’s head of state.

Watch the video presentation from our April 2021 meeting via this link.

Victor and Evie

On April 28, 2021, Dorothy Phillips, author and longtime HSO member, told us about researching and writing the story of the Duke of Devonshire during his time as Governor General of Canada.

Queen Victoria Chooses Ottawa

31 December 1857

Almost everybody knows that Queen Victoria selected Ottawa as Canada’s capital. But few are aware that the city’s selection was anything but a genteel affair. In fact, the Queen was only asked to help after years of sterile political wrangling between contending factions in Parliament. There were more than 200 votes on the issue. Even after the Queen had made her choice, it didn’t go down well with some and was challenged in Parliament. At the end of the day, Canadian legislators only narrowly ratified the Queen’s decision; a change of three votes from yea to nay would have nixed it.

It all began with the merger of Upper and Lower Canada to create the united Province of Canada in 1841 consisting of Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec), each equally represented in Parliament, under the joint leadership of a premier from each of the two Canadas. The Governor-General, Lord Sydenham, convened the first opening session of the united parliament at Kingston on 14 June 1841. While Kingston residents were delighted to be living in the de facto capital of Canada, others were less enamoured with Lord Sydenham’s choice. Canada East representatives had hoped that either Quebec or Montreal would have been chosen as both were far larger in population and had more to offer in the way of amenities for debate-weary members of parliament. However, Canada West was insistent on hosting the new capital. As Kingston satisfied Canada West’s requirement, Canada East representatives reluctantly acquiesced on the grounds that at least it wasn’t Toronto.

But Toronto-area MPs weren’t satisfied either. They submitted a bill calling for Parliament to meet alternatively in the old capitals of Toronto and Quebec City. This bill passed though the outcome satisfied few. MPs agreed in 1842 to examine three resolutions each favouring a different city as the permanent capital—Montreal, Toronto, or Bytown, as Ottawa was then called. All motions were defeated, with Bytown receiving the fewest votes, only 6 for against 57 opposed.

In 1843, Canada’s Attorney General moved that Montreal be chosen as the capital. This motion passed on a vote of 55 to 22. Toronto and Quebec City were rejected as being too far from the geographic centre of the newly united Province of Canada. Bytown too failed despite its favourable geographic attributes—it bordered both provinces, was pretty much equidistant between Toronto and Quebec, and was located at the mouth of the militarily important Rideau Canal, safely distant from the United States. But politicians and bureaucrats looked in horror at the idea of decamping to an isolated “Arctic lumber village,” with a population of perhaps 5,000. Its tumbledown wooden buildings offered few creature comforts, especially in the midst of a harsh Canadian winter. Cosmopolitan Montreal was a far better choice. There, public servants could enjoy the social and commercial attractions of a well-established city that boasted a population ten times that of Bytown. It was also located on the St. Lawrence, Canada’s vital trade route to the Atlantic.

In November 1844, after months of renovations to St. Anne's Market to accommodate Parliament, the capital moved from Kingston to Montreal. Montreal had seemingly won the day. However, less than five years later, Montreal blotted its copy book when a mob protesting the passage of the Rebellion Losses Act that compensated “rebels” as well as “loyalists” for property destroyed in the 1838 Rebellion burnt down Canada’s Parliament buildings. Reconvening in Toronto, politicians decided against returning to unstable Montreal and instead agreed once again that Parliament would alternate between Toronto and Quebec City. This was a patently nutty decision given the difficulty and cost of moving Parliament and its supporting bureaucrats and files every few years—the Grand Trunk Railway linking Toronto to Quebec had yet to be built.

In 1854, Sir Richard Scott, the mayor of Bytown and later member of the Legislative Assembly for Ottawa, renewed the campaign to make Bytown the capital. In 1856, Canada’s Attorney General moved for a definitive selection of a permanent capital. MPs were given a choice between Toronto, Hamilton, Quebec, Montreal, Kingston, and newly re-named Ottawa. In a veritable blizzard of motions for and against each city, Quebec City emerged the victor by a vote of 64 to 56. The lower house also voted in favour of providing £50,000 ($250,000) to fund the construction of new legislature buildings. Unfortunately, the Legislative Council (equivalent to today’s Senate) refused to support the funding. No funding meant no capital for Quebec City.

The political impasse continued into 1857. In a series of motions, Ottawa garnered only 11 supporters out of a 130-member house though no other city could attract a majority. To break the impasse, a resolution asking Queen Victoria to make the choice passed the Legislative Assembly, though only over stiff opposition by members who considered royal mediation as undermining the Canadian government’s newly-gained responsibility for domestic affairs. The mayors of Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Kingston and Quebec City subsequently received letters from the Governor-General, Sir Edmund Head, asking them to prepare papers setting out their respective cities’ merits.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1854. Photo by Roger Fenton.This set in motion feverous activity in candidate cities. In Ottawa, the City Council set up a special meeting of leading citizens, including Sir Richard Scott and Mr. R. J. Friel, to draft a memorial to the Queen setting out Ottawa’s many advantages. Other cities did likewise. Kingston, Montreal and Quebec also sent delegations to London to lobby for support. In the end, Ottawa won the day, a choice favoured by the Governor General. Some say that Ottawa also received unofficial support from Lady Head, the G-G’s wife, who apparently was a good friend of the Queen. The story goes that the Heads had been invited to a picnic lunch in Ottawa held at what would later become Major’s Hill Park. Enchanted with the area and its wonderful river views, Lady Head, an amateur watercolourist, made a number of sketches that she shared with the Queen. Ottawa apparently had other high placed supporters, including Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s Consort.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1854. Photo by Roger Fenton.This set in motion feverous activity in candidate cities. In Ottawa, the City Council set up a special meeting of leading citizens, including Sir Richard Scott and Mr. R. J. Friel, to draft a memorial to the Queen setting out Ottawa’s many advantages. Other cities did likewise. Kingston, Montreal and Quebec also sent delegations to London to lobby for support. In the end, Ottawa won the day, a choice favoured by the Governor General. Some say that Ottawa also received unofficial support from Lady Head, the G-G’s wife, who apparently was a good friend of the Queen. The story goes that the Heads had been invited to a picnic lunch in Ottawa held at what would later become Major’s Hill Park. Enchanted with the area and its wonderful river views, Lady Head, an amateur watercolourist, made a number of sketches that she shared with the Queen. Ottawa apparently had other high placed supporters, including Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s Consort.

The Queen received all the documents by October 1857. After reviewing the material sent to her and consulting with her advisers, she selected Ottawa. Her decision was officially relayed to Canada’s Governor General by Henry Labouchere, the Colonial Secretary, in a letter dated 31 December 1857.

This did not end the debate, however. A motion asking the Queen to reconsider her decision was introduced in July 1858 by the opposition led by The Globe newspaper’s radical editor George Brown. The opposition motion passed the House by a vote of 64 to 50. Then things got really weird. The defeated Conservative-led government of John A. Macdonald and George Étienne Cartier, his Canada East confederate, resigned, howling that the opposition motion was an affront to the Crown. With George Brown and his Canada East ally, Antoine-Aimé Dorion, assuming power, it looked like Ottawa’s hopes to be the capital were to be dashed. But the Brown-Dorion government fell after only four days.

J. A. Macdonald, 1858. Unknown photographer.Under the legislative rules of the day, newly appointed Cabinet ministers were obliged to resign their parliamentary seats and seek re-election before assuming their positions. Brown’s newly minted ministers duly resigned following their appointments. In a snap vote of no confidence, Macdonald and Cartier defeated the new Brown-Dorion administration shorn of its Cabinet ministers. When the Governor General refused to call a general election, Brown resigned, and Macdonald and Cartier were asked back to form a government.

J. A. Macdonald, 1858. Unknown photographer.Under the legislative rules of the day, newly appointed Cabinet ministers were obliged to resign their parliamentary seats and seek re-election before assuming their positions. Brown’s newly minted ministers duly resigned following their appointments. In a snap vote of no confidence, Macdonald and Cartier defeated the new Brown-Dorion administration shorn of its Cabinet ministers. When the Governor General refused to call a general election, Brown resigned, and Macdonald and Cartier were asked back to form a government.

Everybody thought that Macdonald and his new ministers would also resign their seats and seek re-election, leaving the new Conservative government at Brown’s mercy. But, taking advantage of another Parliamentary rule that allowed ministers to change portfolios within a 30-day period without having to seek re-election, Macdonald simply appointed the ministers in his old government to different Cabinet posts before reshuffling them back to their original positions. Macdonald, temporarily Postmaster General, ended up as Deputy Premier rather than Premier in the new government. It seems that the Governor General was worried about the optics of Macdonald regaining the premiership and insisted that Cartier become Premier, at least officially. This sneaky, or brilliant (depending on your point of view), political manoeuvre became known as “The Double Shuffle.” With Brown-Dorion out and MacDonald-Cartier back in, Ottawa’s prospects were restored.

There was one more vote to ratify Queen Victoria’s decision. Held in early 1859, the vote in favour of Ottawa squeaked through with a majority of only five votes.

Sources:

City of Ottawa, 2014. A Virtual Exhibit: Ottawa Becomes the Capital, http://ottawa.ca/en/residents/arts-culture-and-community/museums-and-heritage/virtual-exhibit-ottawa-becomes-capital-0.

Joseph Edmund Collins, 1883. Life and Times of the Right Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald, Rose Publishing Company, Toronto.

Gwyn, Richard, 2007. The Man Who Made Us: The Life and Times of Sir John A. Macdonald. vol 1: 1815-1867. Random House Canada.

Hamnett P. Hill, K.C., 1935. “The Genesis of our Capital,” Bytown Pamphlet Series #3, Ottawa Historical Society.

The Ottawa Evening Citizen 1925. “How Ottawa Was Chosen The Capital of The Dominion,” 25 June.

——————, 1930. “When Queen Victoria Made Ottawa Capital,” 22 May.

Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2013. “Parliament Hill, Pre-construction, 1826-58,” http://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/collineduparlement-parliamenthill/batir-building/hist/1826-1858-eng.html.

Image: J. A. Macdonald, 1858, unknown, File:John A Macdonald in 1858.jpg - Wikipedia

Image: Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1855, Roger Fenton, http://www.robswebstek.com/2009/04/queen-victoria-prince-albert-1855.html.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Buchan’s Talents Bedazzled Author

Lord Tweedsmuir was Governor General of Canada from 1935 until 1940. Tweedsmuir’s remarkable memory, writing capacity, and skill in working with people were what first drew the attention of Bill Galbraith, the speaker at the Ottawa Historical Society's afternoon meeting on January 29, 2020. Bill ended up writing a book about Lord Tweedsmuir, published in 2013, titled John Buchan: Model Governor General.

John Buchan, before being made a Baron by King George V in 1935, was a well-known journalist and author, having written over 100 books. He wrote the spy thriller The Thirty- Nine Steps in 1915. In 1935 Alfred Hitchcock made it into a movie, which can still be seen on YouTube. Written over 100 years ago, the book has never been out of print. The Guardian newspaper places it 42nd on its list of 100 best novels written in English. The Ottawa Public Library still has 21 of Buchan’s books in its online catalogue.

John Buchan was born in 1875 to a Scottish preacher. His mother, Helen Masterson, was from a sheep farming family in the border area of southern Scotland. Buchan spent his boyhood summers on the farm where he developed a love of the outdoors, hiking, and fishing along the River Tweed.

At age 17, Buchan entered Glasgow University to receive a classical education. Even at this young age, he had a commission from a London publisher to edit a book on the philosopher Francis Bacon. Buchan’s first book, a collection of Bacon’s essays, was published in 1894, when Buchan was 19 years old. The next year he published his first novel. Winning a scholarship, he went on to Oxford University to continue his studies in the classics. After graduation he moved to London and started at a solicitor’s office. In June 1901 he was called to the bar, specializing in commercial law.

From September 1901 to July 1903 he was in South Africa as a secretary to the High Commissioner, working on reconstruction after the Boer War. While there he met Commonwealth troops, including Canadians, from whom he gained an appreciation of their strong sentiments and pride for their respective countries.

Returning to London, Buchan worked in law, wrote for the Spectator magazine, and became a literary advisor to Thomas Nelson publishers. In 1905 he met Susan Grosvenor, a member of an aristocratic family. They married in July 1907. They had four children, one of whom married a woman from Ottawa.

At the start of World War One in 1914, Buchan was rejected for military service because of a duodenal ulcer. This was to plague him for the rest of his life. He began to write a contemporary history of the war for Nelson, with a lag of only a few months. This brought him to the attention of the Times newspaper.

He became its war correspondent. In the fall of 1915, The 39 Steps and eight volumes of his history of the war were published. Now the military took notice. He was commissioned a Lieutenant in the Intelligence Corps serving in France. In 1916, he published Greenmantle, another novel featuring Richard Hannay. Buchan was soon promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and returned to London to head an information department. In February 1917 his duodenal ulcer was operated on. In 1918 he became Head of Intelligence reporting to the Minister of Information, Lord Beaverbrook, a Canadian. Buchan finished his 24-volume war history in 1919.

After the war, in May 1919, a chance meeting occurred between Mackenzie King and the Buchans in London. King was struck by Buchan’s “scholarly appearance and his delightful English manner”. They both had Scottish backgrounds. Later that year, King became federal Liberal leader.

In 1924, King invited the Buchans, on their way to the U.S. on business, to Ottawa. King showed them around Ottawa and his estate at Kingsmere. The visit cemented an intellectual and spiritual attraction to Buchan in King’s mind. This was a factor when a successor to Gov. Gen. Lord Bessborough was to be considered. In 1927, Buchan became a U.K. Member of Parliament.

Finding a successor to Lord Bessborough, who was retiring, began in 1934 and ran into 1935. Opposition leader King was influential in having King George V select Buchan as a replacement. In March 1935, Buchan was named the future Governor General of Canada. King was happy, although a controversy arose. Buchan was a commoner, traditionally the appointment was of someone from the House of Lords. And why could the GG not be Canadian born? King George V wanted to be represented by a peer, so he raised Buchan to become a Baron. Buchan chose the name Tweedsmuir to reflect his Scottish roots.

The viceregal couple arrived in Canada on Nov. 2, 1935. Lord Tweedsmuir was sworn in as the 15th Governor General of Canada. Since he was well known for his popular books, people felt closer to him than they had towards any of his predecessors. Buchan knew the importance of his official role, but saw another role, too: to reach out to Canadians and encourage excellence. Susan Tweedsmuir soon became engaged in her own right. She took over speaking to women’s clubs to relieve John of certain duties.

Initially, discussions between King and Tweedsmuir were not smooth, but Tweedsmuir showed himself to be adroit in working with people. He provided assistance to King to better organize the office of the Prime Minister. He played a substantive role in the early stages of modernizing Canada’s machinery of government, helping to define the Prime Minister’s Office and the position of Clerk of the Privy Council.

Tweedsmuir was helpful during the abdication crisis of Edward VIII. He also was instrumental in having King George VI and Queen Elizabeth tour Canada in 1939 as a way of pointing out Canada’s independence from Britain. The visit was a huge success. It raised the country’s morale and boosted national unity.

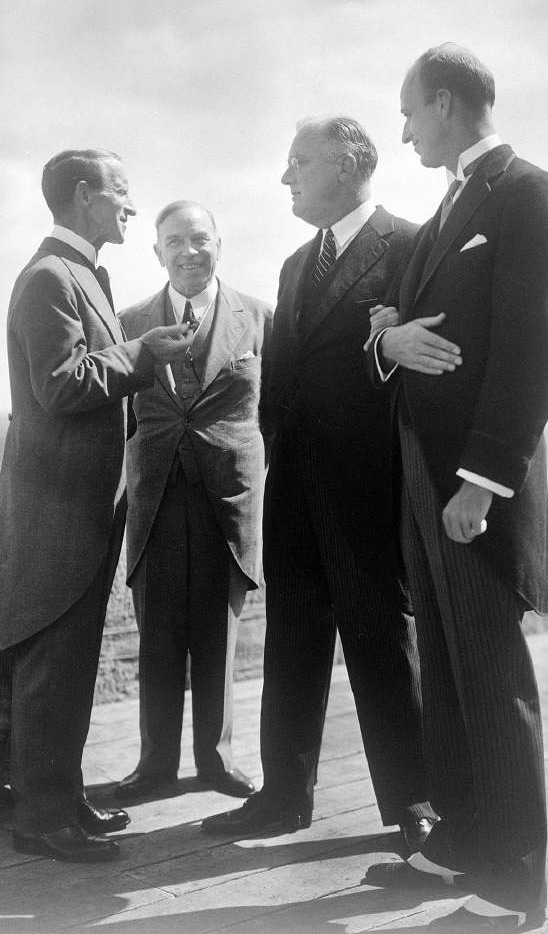

Gov. Gen. Lord Tweedsmuir (left) speaking with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (supported by his son James, right), with Prime Minister Mackenzie King looking on — July 1936, Quebec City. LAC PA164243.John Buchan became a bridge between Britain and North America. He developed a strong relationship with U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Due to isolationist sentiment in the U.S., it was easier for Roosevelt to deal with Tweedsmuir than with Britain directly.

Gov. Gen. Lord Tweedsmuir (left) speaking with U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (supported by his son James, right), with Prime Minister Mackenzie King looking on — July 1936, Quebec City. LAC PA164243.John Buchan became a bridge between Britain and North America. He developed a strong relationship with U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Due to isolationist sentiment in the U.S., it was easier for Roosevelt to deal with Tweedsmuir than with Britain directly.

In their first two years in Canada, the Tweedsmuirs travelled extensively. During a major train journey through western Canada in 1936, Lady Tweedsmuir asked people along the way what she could do for them. They requested books. Susan initiated and personally managed what became known as the Lady Tweedsmuir Prairie Library Scheme. Books, 40,000 of them, were collected and sorted at Rideau Hall and delivered to the Prairies, all funded through private foundations.

In 1937 they travelled to the Maritimes. In the same year Lord Tweedsmuir travelled along Alexander Mackenzie’s path down the Mackenzie River to Aklavik at the river delta, then flew to Great Bear Lake and on to Kugluktuk, called Coppermine at that time. These travels gave Canadians a better perspective of their own land. As well, it provided inspiration for Buchan to write further books. Also, through his travels, Tweedsmuir provided new visions for government action. After discussions with Canadian literary groups, Lord Tweedsmuir established the Governor General Literary Awards in 1936. Tweedsmuir’s incredible memory particularly impresses Bill Galbraith. Because of Buchan’s remarkable memory, he could speak to almost any group or profession. This helped to make him a man of the people.

On the morning of February 6, 1940 while preparing for another full day, Tweedsmuir suffered a stroke. Treatment by Dr. Wilder Penfield could not save him. Tweedsmuir died on February 11, 1940.

The outpouring of grief, gratitude, and admiration was enormous. John Buchan felt himself to be Canadian. He was known and loved across the country. He was a model Governor General.

An Important Message from the Governor General of Canada

Dear members of the Historical Society of Ottawa,

As patron of your organization, I wanted to send along my best wishes to you during these difficult times. I hope you are well.

Wherever you are and whatever you do, you are facing a historic and unprecedented challenge alongside people and organizations from around the world. And you are tackling it head-on.

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed everything and it is affecting every aspect of our society. This invisible enemy is scary and strong, and it has forced us to change the way we live. It calls on each of us to sacrifice our freedom of movement and to accept demanding conditions. In many cases, at great cost.

To defeat the virus, it requires all of us to do our part. Every single one of us. No doubt you are already doing all you can. But what more can we do?

Let’s encourage.

Continue to support everyone helping Canadians during the pandemic. The office of the governor general is proud to play a part in raising awareness and giving thanks. Please lend your voice too.

Let’s amplify.

We can reach out to Canadians by relaying official information and instructions. I invite you to visit www.gg.ca and to share our content, particularly how organizations a re making a difference in our communities.

Let’s be grateful.

One cannot choose when hardship comes, but one can choose how to respond to it in times of crisis. Please visit Caring Nation, our new online forum, to contribute stories of solidarity and compassion from all over the country.

We are now steadfastly staying the course. It will take time, but when we return to brighter days, we will look back on these challenging times and realize that because we all did our part, we emerged stronger as a nation. Our collective resilience will lead to our collective victory.

In the meantime, as we hold the line, let us focus not on what we cannot control, but on the news that give us hope.

Please stay in touch. Talk to us on social media @GGJuliePayette on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube. And above all, stay safe and healthy.

We are all part of the fight against COVID-19.

Yours most sincerely,

Julie Payette

Governor General of Canada

Patronage of Rideau Hall

Lady Minto

Lady Minto

Topley Studio, Library and Archives Canada, 3810248Since the founding of what was then called the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898, the Society has always had a close relationship with Rideau Hall There is a belief that Lady Aberdeen, the wife of the 7th Earl of Aberdeen who was Canada’s Governor General from 1893 to1898, was the Society’s first patron. However, while we know that she took a close interest in the fledgling organization, her patronage was likely unofficial as she and her husband returned to Britain just a few days after the first regular meeting of the Society.

For certain, Lady Minto, the wife of the 4th Earl of Minto who succeeded Lord Aberdeen, consented to become the patron of the Society in February 1899. For more than fifty years, the wives of succeeding Governors General continued this practice. In more recent decades, Governors General themselves have fulfilled this role, continuing a tradition of more than a hundred and twenty years of vice-regal patronage.

Our History

(Drawn from Mullington, Dave, 2013. “To Be Continued…A Short History of the Historical Society of Ottawa,” HSO Publication No. 88.)

Lady Matilda Edgar, née Ridout, (1844-1910), wife of Sir James Edgar, Speaker of the House of Commons, chaired the inaugural meeting of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archive Canada, PA-025868On June 3, 1898, thirty-one Ottawa women, united by a desire to preserve and conserve Canada’s historical heritage, assembled in the drawing room of the Speaker of the House of Commons located in the old Centre Block on Parliament Hill. Chairing the meeting was the prominent author and early feminist Lady Matilda Edgar (née Ridout) wife of Sir James Edgar, the Speaker. The cream of Ottawa society attended the meeting, including Lady Zoë Laurier, the wife of the then Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Mrs Adeline Foster, the wife of the prominent Conservative politician Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, and Mrs Margaret Ahearn, the spouse of Mr Thomas Ahearn, the famous Ottawa-born inventor and businessman. The ladies agreed to form the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. As reported by the Ottawa Journal, they hoped “to resurrect from oblivion things of interest to every patriot Canadian woman, and preserve such things that are already treasures.”

Lady Matilda Edgar, née Ridout, (1844-1910), wife of Sir James Edgar, Speaker of the House of Commons, chaired the inaugural meeting of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archive Canada, PA-025868On June 3, 1898, thirty-one Ottawa women, united by a desire to preserve and conserve Canada’s historical heritage, assembled in the drawing room of the Speaker of the House of Commons located in the old Centre Block on Parliament Hill. Chairing the meeting was the prominent author and early feminist Lady Matilda Edgar (née Ridout) wife of Sir James Edgar, the Speaker. The cream of Ottawa society attended the meeting, including Lady Zoë Laurier, the wife of the then Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Mrs Adeline Foster, the wife of the prominent Conservative politician Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, and Mrs Margaret Ahearn, the spouse of Mr Thomas Ahearn, the famous Ottawa-born inventor and businessman. The ladies agreed to form the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. As reported by the Ottawa Journal, they hoped “to resurrect from oblivion things of interest to every patriot Canadian woman, and preserve such things that are already treasures.”

Under its original 1898 Constitution, the objective of the Society was to encourage “the study of Canadian History and Literature, the collection and preservation of Canadian historical records and relics, and the fostering of Canadian loyalty and patriotism.” The Constitution also stressed that “neither political parties nor religious denominations” would be recognized. Adeline Foster was elected as the Society’s first president. Lady Aberdeen (née Ishbel Maria Marjoribanks), the wife of the Governor General, consented to be the Society’s patron, thereby establishing a link to Rideau Hall that continues to this very day. The annual membership fee was set at fifty cents. Initially, the Society was a women-only organization, though men sometimes participated as honorary members. This situation continued until 1955, when men were allowed to join the Society as full members.

Lady Zoé Laurier, née Lafontaine, (1841-1921), wife of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada, was a founding member of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archives Canada, PA-028100During the early years of the Society’s history, particular attention was paid to the collection and preservation of important artifacts and historical documents. The Society put on its first exhibition of historical objects in 1899. This collection, which was to expand greatly over the coming decades, went on permanent display with the opening in 1917 of the Bytown Historical Museum, located in the old Registry Office on Nicholas Street. The museum was staffed and operated by Society volunteers. Other activities included regular lectures and the publication of historical research. The Society was also instrumental in the erection of the statue of the French explorer Samuel de Champlain at Nepean Point in 1915. To celebrate Ottawa’s centenary in 1926, the Society unveiled a memorial to Lieutenant-Colonel John By, the Royal Engineer responsible for the construction of the Rideau Canal, and the founder of Bytown. A replica of his house, which had been destroyed by fire years earlier, was also built at Major’s Hill Park.

Lady Zoé Laurier, née Lafontaine, (1841-1921), wife of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada, was a founding member of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archives Canada, PA-028100During the early years of the Society’s history, particular attention was paid to the collection and preservation of important artifacts and historical documents. The Society put on its first exhibition of historical objects in 1899. This collection, which was to expand greatly over the coming decades, went on permanent display with the opening in 1917 of the Bytown Historical Museum, located in the old Registry Office on Nicholas Street. The museum was staffed and operated by Society volunteers. Other activities included regular lectures and the publication of historical research. The Society was also instrumental in the erection of the statue of the French explorer Samuel de Champlain at Nepean Point in 1915. To celebrate Ottawa’s centenary in 1926, the Society unveiled a memorial to Lieutenant-Colonel John By, the Royal Engineer responsible for the construction of the Rideau Canal, and the founder of Bytown. A replica of his house, which had been destroyed by fire years earlier, was also built at Major’s Hill Park.

Mrs Adeline Foster, née Chisholm, (1844-1919), wife of Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, Conservative politician, first president of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada, Mikan No. 3423435During the lean years of the Great Depression, the Society was forced to tailor its activities to suit the straitened financial circumstances. Its publications were cut back, and a ten cent fee began to be charged for museum entry. In 1930, the annual membership fee was also increased to one dollar. Notwithstanding the difficult economic situation, the Society continued to flourish. Its collection of historical artifacts and books expanded. Meetings, historical outings, and presentations were held regularly. In 1937, the Society was officially incorporated by the Province of Ontario. With the outbreak of World War II, Society activity slowed to allow members more time to support the war effort. The museum was closed for the duration. Nonetheless, membership meetings continued to be held, and the Society’s collection of antiquities grew through donation. Members also raised money for deserving wartime causes.

Mrs Adeline Foster, née Chisholm, (1844-1919), wife of Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, Conservative politician, first president of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada, Mikan No. 3423435During the lean years of the Great Depression, the Society was forced to tailor its activities to suit the straitened financial circumstances. Its publications were cut back, and a ten cent fee began to be charged for museum entry. In 1930, the annual membership fee was also increased to one dollar. Notwithstanding the difficult economic situation, the Society continued to flourish. Its collection of historical artifacts and books expanded. Meetings, historical outings, and presentations were held regularly. In 1937, the Society was officially incorporated by the Province of Ontario. With the outbreak of World War II, Society activity slowed to allow members more time to support the war effort. The museum was closed for the duration. Nonetheless, membership meetings continued to be held, and the Society’s collection of antiquities grew through donation. Members also raised money for deserving wartime causes.

The Bytown Museum, formerly the Commissariat building, was built in 1827 and is the oldest stone building in OttawaFollowing the conclusion of the war, Society activities picked up. Particular attention was paid to finding a new home for the organization’s growing collection of historical artifacts and books; the old Registry Building was no longer adequate. In 1951, the Society leased premises from the federal government for a nominal fee in the Commissariat building adjacent to the Rideau Canal locks. The building, the oldest stone structure in Ottawa, was built by Scottish stonemasons hired by Colonel By during the construction of the Rideau Canal during the 1820s. Unfortunately, it was in a poor state of repairs; the building’s restoration and renovation occupied a considerable portion of the Society’s time, effort, and resources over coming years.

The Bytown Museum, formerly the Commissariat building, was built in 1827 and is the oldest stone building in OttawaFollowing the conclusion of the war, Society activities picked up. Particular attention was paid to finding a new home for the organization’s growing collection of historical artifacts and books; the old Registry Building was no longer adequate. In 1951, the Society leased premises from the federal government for a nominal fee in the Commissariat building adjacent to the Rideau Canal locks. The building, the oldest stone structure in Ottawa, was built by Scottish stonemasons hired by Colonel By during the construction of the Rideau Canal during the 1820s. Unfortunately, it was in a poor state of repairs; the building’s restoration and renovation occupied a considerable portion of the Society’s time, effort, and resources over coming years.

In 1955, there was a dramatic shift in the life of the Society. After vigorous debate, men were permitted to become full members of the Society in order to build a broader and stronger organization. The following year, the Society’s new name—the Historical Society of Ottawa—was officially adopted to reflect that change. Mr H. Townley Douglas, who had been previously active as an honorary member was elected as the Society’s first male director.

In Major's Hill Park stands the statue of Col. John By, Royal Engineers, who was responsible for building the Rideau Canal and the founding of Bytown, later renamed OttawaWhile the Bytown museum remained at the centre of the Society’s activities, the 1960s, under the leadership of Dr Bertram McKay, saw the HSO working hard for the erection of a statue in honour of Colonel By. Although Ottawa’s mayor at the time, Dr Charlotte Whitton, and City Council were supportive, it was up to the Historical Society to come up with the necessary funds. Raising $36,500 by 1969 (equivalent to more than $233,000 in today’s money), the Society hired the Quebec-born sculptor Joseph-Émile Brunet. On August 14, 1971, Governor General Roland Michener unveiled the bronze statue of Colonel By in Major’s Hill Park. Fittingly, the statue overlooked the Rideau Canal, itself a lasting memorial to the Colonel’s engineering abilities.

In Major's Hill Park stands the statue of Col. John By, Royal Engineers, who was responsible for building the Rideau Canal and the founding of Bytown, later renamed OttawaWhile the Bytown museum remained at the centre of the Society’s activities, the 1960s, under the leadership of Dr Bertram McKay, saw the HSO working hard for the erection of a statue in honour of Colonel By. Although Ottawa’s mayor at the time, Dr Charlotte Whitton, and City Council were supportive, it was up to the Historical Society to come up with the necessary funds. Raising $36,500 by 1969 (equivalent to more than $233,000 in today’s money), the Society hired the Quebec-born sculptor Joseph-Émile Brunet. On August 14, 1971, Governor General Roland Michener unveiled the bronze statue of Colonel By in Major’s Hill Park. Fittingly, the statue overlooked the Rideau Canal, itself a lasting memorial to the Colonel’s engineering abilities.

In 1981, the Society took a new step in its effort to increase public awareness of Ottawa and the Ottawa Valley’s rich history with the launch of a pamphlet series dedicated to that purpose. Its first publication was titled John Burrows and Others on the Rideau Waterway by a former Society president Charles Surtees. The pamphlet series continues to be an important feature of the Society’s efforts to increase public awareness about the history of Ottawa.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, the museum became an increasing preoccupation and concern for Society members. Forced to relocate temporarily due to restoration work conducted by the federal government at the Commissariat building and Rideau locks, attendance plummeted. Even when the Bytown Museum reopened at the Commissariat Building, the number of visitors was subsequently adversely affected by the reconstruction of Plaza Bridge. Declining membership, fewer volunteers, and rising costs owing to inflation also strained the Society’s ability to sustain the Museum in the manner it deserved. After considerable soul searching and debate, the difficult decision was made in 2003 to transfer the Bytown Museum to a separate not-for-profit organization. Roughly half of the artifacts and rare books collected over more than a century were loaned to the Museum; the loan became a permanent gift two years later. Considerable funds were also transferred to the new Museum Board to help launch the new organization.

Although now legally separate from the Historical Society of Ottawa, the Museum and the Society continue to cooperate closely. Over the following years, the Society transferred its remaining collection of items to other heritage organizations, most importantly the City of Ottawa Archives. A large collection of military medals was also offered to Canadian museums. Those medals that could not be placed were subsequently sold. In 2011, the proceeds of the sale helped to launch the Historical Society of Ottawa’s Research and Development Fund to support research into Ottawa’s history.

In 2013, the Society reviewed and approved revised “purposes and objectives” (Article 2 of its Constitution) in light of the many changes to the organization in recent years. Remaining true to the spirit of its founding members, the Society remains focused on increasing public awareness and knowledge of the history of Ottawa, the surrounding region, and their peoples. In cooperation with other heritage organizations, it also works to conserve archival materials, supports and encourages heritage conservation, and preserves the memory of Colonel By.