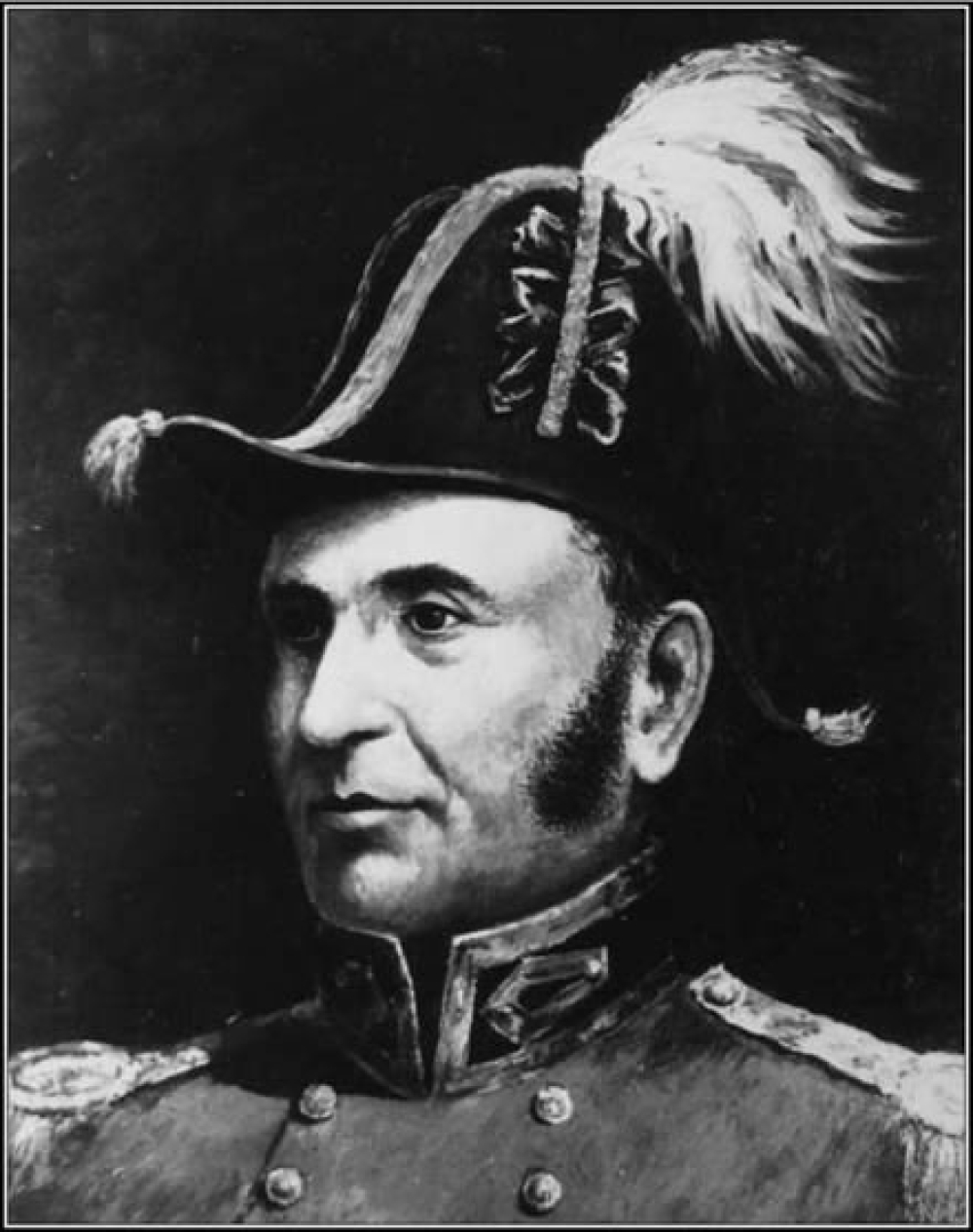

Who better to share the story of the Bytown’s beginnings than Lt. Colonel John By himself? Who more reliable to recount the construction of the Rideau Canal than the Royal Engineer who had overseen this remarkable project?

André Pinard constructs what an interview might have been like, between Colonel By and a newspaper editor, at the conclusion of construction of the Rideau Canal.

As an added bonus, André presents this fictive conversation in the form of scripted play. What a wonderful opportunity for educators who might wish offer students a glimpse into Ottawa’s past by re-enacting this play in their classrooms.

André Pinard is originally from Ottawa’s Lower Town. André pursued a career in education in Northern Ontario and the Ottawa region.

Colonel By and the Founding of Bytown

By André Pinard

This fictive conversation takes place on September 3, 1832, in the sitting room of Lieutenant-Colonel John By ’s residence on Nepean Point, overlooking Entrance Bay and the Rideau Canal at Bytown.

He is being interviewed by Thomas Dalton, editor of The Patriot and Farmer ’s Monitor, a Kingston weekly newspaper.

Mr. Dalton: Good afternoon, Sir.

Colonel By: A very good afternoon to you. It is a pleasure to make your acquaintance. How does Kingston prosper of late?

Mr. Dalton: Kingston fares well, I thank you. Since the completion of the canal, it has prospered in many ways. The town is alive with soldiers, merchants, canal workers, and settlers, and I daresay it has grown considerably in strategic importance in recent years.

Colonel By: Quite so. I am pleased to hear it.

Mr. Dalton: Thank you, Sir, for receiving me in your handsome home overlooking Entrance Bay and the Rideau Canal. You command a splendid prospect indeed.

Colonel By: From this vantage, I can observe the batteaux and paddle boats as they arrive and depart, and thus keep myself apprised of local affairs. You must, however, pardon the state of the house; we shall be leaving for England very shortly.

Did you travel from Kingston by way of the canal?

Mr. Dalton: Indeed I did, Sir, aboard the now-famous paddle boat Pumper. What a prodigious work the Rideau Canal is—a remarkable feat of engineering and a lasting testament to British ingenuity and perseverance. I was overwhelmed by the number of great dams and locks—here at Entrance Bay, at Hog’s Back, at Jones Falls, and elsewhere besides. And its length, Sir—truly astounding.

Colonel By: Most assuredly. The canal extends some 123 miles from Bytown to Kingston and comprises 52 dams and 47 masonry locks, all completed within five summer working seasons. It reflects not only British expertise, including that of the Royal Sappers and Miners, but also the tireless labour of more than 2,000 Irish, Scots, and French Canadian labourers and tradesmen. Many worked in the harshest conditions, and many, regrettably, lost their lives through sickness or accident.

Mr. Dalton: I understand that you yourself made the first official passage through the completed canal last May.

Colonel By: I did indeed have that honour, sailing from Kingston Mills to Bytown aboard the steamship Pumper, renamed Rideau for the occasion. It was a memorable event, and we were greeted warmly at every lock, with much rejoicing and ceremony.

Smiths Falls, in particular, left a strong impression. We arrived there near four o’clock in the morning, announcing our presence with a cannon shot, which the townspeople promptly returned. As the crowd gathered along the dock, we disembarked to greet them, and upon our departure received a final salute. The experience made a deep impression upon our young daughters, who accompanied my wife and me on this inaugural voyage.

Mr. Dalton: Why was the Rideau Canal built?

Colonel By: The canal was conceived as a military necessity for the defence of Upper Canada. Kingston’s fortress and naval yard were vital to British control of the Great Lakes, yet supply by way of the St. Lawrence River was both difficult and vulnerable to American attack, given the river’s proximity to the United States border.

An inland route was therefore required to move troops, artillery, and supplies securely between Montreal and Kingston. By 1825, a canal linking the Ottawa River to Lake Ontario was deemed essential to the colony’s defence.

Mr. Dalton: There was much sickness among the workers, I understand?

Colonel By: Indeed there was, and no man was spared. Disease was widespread throughout the works. Swamp fever, ague, dysentery, and smallpox afflicted labourers and their families alike. I myself suffered repeated bouts of fever and was bled on two occasions. Quinine was the sole effective remedy, though its cost and scarcity limited its use. In 1828, an epidemic proved so severe that work was temporarily halted. Losses from illness and accident were grievous, and it is estimated that nearly one thousand lives were lost during the undertaking.

Mr. Dalton: Why was Entrance Bay chosen over Lebreton’s Flats, or a route east of the Rideau Falls, as Samuel Clowes had proposed?

Colonel By: Mr. Clowes’s route was carefully considered, but it would have required extensive blasting through solid rock. We therefore selected Sleigh Bay, which offered greater defensibility and proved far easier to excavate, being composed largely of sand and gravel.

Mr. Dalton: And why not select Captain John Lebreton’s property at Richmond Landing?

Colonel By: Quite frankly, it would have offered a shorter and easier approach to Dow’s Great Swamp. However, the Earl of Dalhousie would not entertain the idea. His dispute with Captain Lebreton over the price of the land rendered it impossible.

Moreover, His Excellency had already acquired, as early as 1823, the lands adjoining the present canal site from Barrack’s Hill eastward—excluding Lebreton’s property, which was considered excessively dear.

Mr. Dalton: Bytown bears your name, Sir. You are said to be its founder.

Colonel By: I am honoured by the association, though it might with equal justice have been named Dalhousie, in recognition of His Excellency’s leadership and steadfast support. Without him, neither the canal nor the town would have come to fruition.

At first, in 1826, we referred to the area simply as the Rideau Canal. Then, partly in jest, someone proposed the name By’s Town. Much to my surprise—and protest—it soon became Bytown. For the present, the name endures, though I expect that, as the town grows in size and consequence, it will one day adopt a name more fitting to its geography and history.

This place has borne many names already—Îles aux Chaudières, Barrières, Place des Rideaux, Chaudière Falls, The Point, Richmond Landing, Bellows Landing, and Nepean. The possibilities are many.

Mr. Dalton: Before Bytown was established, were there already people living here?

Colonel By: Most certainly. The Hurons, Algonquins, and Iroquois travelled and traded along this great river, which they called Kitche-sippi, for countless generations. They were the first to behold the Rideau Falls and to portage around the Chaudière. In the days of Cartier and Champlain, it was known as the River of the Algonquins.

After a long and bitter struggle between the Algonquins and the Iroquois over trade, the river lay deserted for many years. In 1654, the Outaouais—members of the Algonquin nation—returned to trade here, and from that time the river has borne the name Ottawa.

Mr. Dalton: And your relations with the local tribes?

Colonel By: They are cordial. The Algonquins often serve as guides and willingly share their knowledge of the land. At the same time, they continue to petition the government to recognize their land claims. That matter remains unresolved and lies beyond my authority.

Mr. Dalton: How long have settlers of European origin been present in this region?

Colonel By: Settlement in the valley began in earnest after 1791. In 1793, four townships—Osgoode, North Gower, Gloucester, and Nepean—were established, forming part of Carleton County. When I arrived seven years ago, development here was minimal. There were but two stores, one stone building, three square timber houses, and a handful of cabins.

Among the early inhabitants were men whose names you may recognize: Nicholas Sparks, John Bellows, and John Lebreton. Although settlements existed farther inland—such as Richmond, a military settlement founded in 1818—there was little activity along this stretch of the river.

Mr. Dalton: And the northern shore?

Colonel By: There the situation is quite different. A community has existed since 1800, founded by Philemon Wright, who arrived from Massachusetts with his family and labourers. He has since become a successful timber merchant, sending great quantities of white pine downriver to Quebec, whence it is shipped to Britain. The population now numbers some one thousand.

Mr. Wright proved indispensable to our efforts, supplying materials and practical knowledge of building in the wilderness. So vital was his assistance that one of my first instructions from the Governor was to construct a bridge over the Chaudière Falls. Completed promptly, it was named the Union Bridge, linking Upper and Lower Canada.

Mr. Dalton: How did you come to be entrusted with the creation of this town and the canal?

Colonel By: I am an officer of the Royal Engineers. I was first dispatched to Canada in 1802, where I oversaw the construction of a canal at Les Cèdres and worked on the fortifications of Quebec. In 1811, I was called to Portugal and served under Wellington and Dalhousie during the Peninsular War. Upon my return to England, I was placed in charge of an armament factory. In March 1826, I was selected to undertake the construction of the Rideau Canal.

Mr. Dalton: You arrived here in September 1826. What were those first days like?

Colonel By: In mid-September, I travelled from Montreal to Wright’s Town with Lieutenant Pooley and a small advance party, including the master stonemason Thomas McKay. We examined the south shore, inspecting bays and the mouth of the Rideau River to determine the most suitable site for the canal’s entrance.

On September 26, Lord Dalhousie joined us. After reviewing my recommendations, he approved Entrance Bay as the canal’s northern terminus, and work commenced at once.

Mr. Dalton: Tell me of the men who worked on the canal.

Colonel By: Thousands laboured at sites throughout the route—Royal Sappers and Miners, contractors, tradesmen, and labourers. The Ordnance supplied provisions at cost, while local farmers furnished meat and produce. Log cabins were erected at many sites, and some families maintained small gardens. At the outset, however, many men lived in tents or in crude shelters dug into the earth. Those were trying times indeed.

Mr. Dalton: And what is Bytown like today?

Colonel By: It remains very much a town in formation. The canal has been delivered as promised, yet the reputation of Bytown as “not a handsome town” is not entirely undeserved. Tensions between Irish and French labourers persist, and there is, regrettably, a good deal of disorder.

Mr. Dalton: You are soon to depart Canada. What lies ahead?

Colonel By: I intend to retire to my estate near Frant, in Sussex, with my wife, Esther March, and our two daughters, Esther and Harriet. First, however, I must answer questions from the British Treasury regarding the expenditures incurred during construction.

Mr. Dalton: How were the canal’s costs originally determined?

Colonel By: The Duke of Wellington approved the canal in 1818 as part of the colony’s defensive strategy. To avoid excessive scrutiny, the project was begun with minimal funding. The initial estimate—£169,000—was wholly inadequate, though I was obliged to proceed.In 1827, I submitted a revised estimate of £474,000. By the canal’s completion six years later, the total cost had risen to £822,000—a sum I believe fully justified.

Mr. Dalton: Finally, Sir, of what are you most proud, and what do you wish for Bytown and the canal?

Colonel By: I take pride in my service, but above all in the people—French, Irish, Scottish, and British—who laboured here between the Rideau and the Chaudière. Many gave their lives. It is my earnest hope that their sacrifice will not have been in vain; that Bytown will continue to grow and prosper; and that the Rideau Canal will one day be recognized as the jewel it truly is.

Mr. Dalton: I thank you and bid you good day, Sir, and Godspeed.

Final historical note

Colonel By handed over command to Captain Bolton on September 1, 1832, and then travelled with his family to Québec City. He departed Canada on October 21, 1832, arriving in England on November 25. Although cleared of questions regarding the canal’s cost, he suffered a setback in his career and spent his final years in retirement. His greatest achievement received widespread recognition only after his death, on February 1, 1836, at his Sussex estate. He never saw his work on the Rideau Canal fully celebrated in his lifetime.

Bibliography

Brault, L., Ottawa Old and New,Ottawa Historical Information Institute, 349 pp., 1946.

Brault, L., The Mile of History, Ottawa, National Capital Commission, 83 pp., 1981.

Historical Society of Ottawa, Lt. Colonel John By, Ottawa, 12 pp., Undated.

Ian R. Dalton, “DALTON, THOMAS,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography , vol. 7, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed December 23, 2025, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/dalton_thomas_7E.html.

Kelsey, E.S., Le colonel By et son époque/ Colonel By and Bygone Days, La Société historique d’Ottawa, 28 pp., 1969.

Lamoureux, G., Bytown et ses pionniers canadiens-français, 1826-1855, Ottawa, 364 pp., 1978

Legget, R., John By, Builder of the Rideau Canal Founder of Ottawa, Historical Siety of Ooawa, 62 pp., 1982.

Leggett, Robert, Ottawa Waterway, Gateway to a continent, University of Toronto Press, Toronto., 1975.

MacTaggart, J., Three Years In Canada,Henry Colborn, London, 2 vols., 347 and 340 pp., 1965.

Mika, Helma and Nick, Bytown, The early days of Ottawa , Mika Publishing Company : Belleville., 1982.

Passfield, Robert, W.,Building the Rideau Canal, A pictorial history . Fitzhenry and White : Markham., 1982

Ross, A.H. D., Ottawa Past and Present,Thorburn and Abbott, Ottawa, 224 pp., 1927.

Note: In the final stages of preparation, the author made use of AI-assisted language tools for spelling, grammar, and stylistic refinements. The research and interpretation presented in this article are entirely the author ’s own.