Richard Collins joined HSO in 2018, when he moved to Ottawa. Although his heritage walking tour business has sent him back to the GTA, he remains part of HSO, as the newsletter editor.

Richard recounts how canals have evolved, in Ottawa and elsewhere.

If Shakespeare had been around to write an article for HSO’s 2026 Bytown200 Bicentennial Storytelling Challenge (stiff competition for the rest of our contributors), two characters would have played a prominent role.

Ottawa, 1910

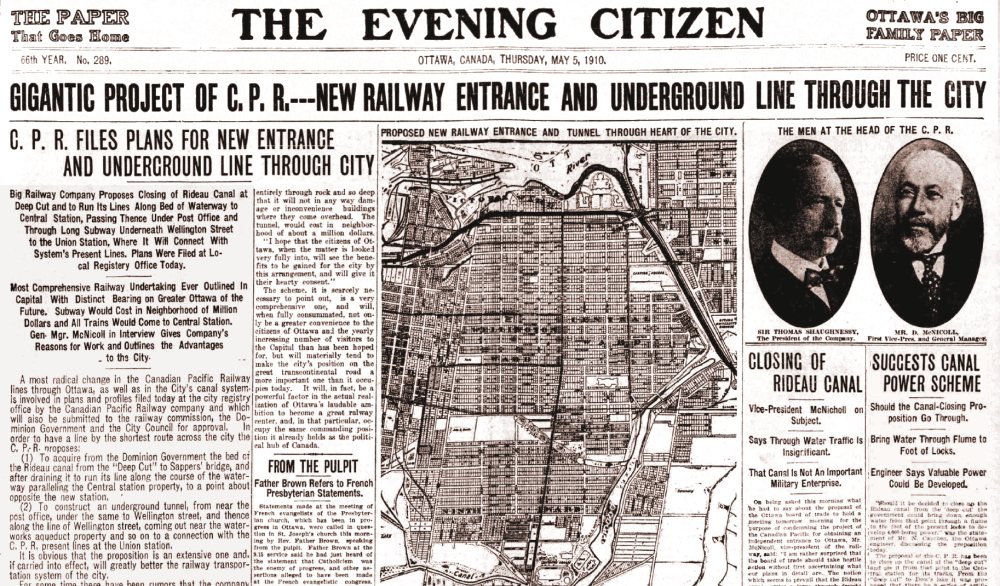

The scheme devised by the two antagonists was there in plain text, on the front page of the Ottawa Citizen, complete with portraits of the perpetrators displayed prominently. The two had come to Ottawa, from CPR’s home base in Montreal, not to praise the Rideau Canal, but to bury it.

Thomas Shuaghnessy was president of Canadian Pacific, and his general manager (and brainchild of the plan) was David McNicoll. (The town of Port McNicoll, on Georgian Bay, is named in his honour, although in Port McNicoll’s case, he was a proponent of marine transportation; not an opponent of it, as we was with the Rideau Canal.)

The part played by the Ottawa Citizen was to help it’s readers understand the logistics, for better or worse, behind Canadian Pacific’s logic to drain the Rideau Canal, pave the basin and lay railway tracks along the razed waterway to a new station that Grand Trunk had recently proposed to build beside the east bank of the canal, on the south side of Rideau Street.

Welland, 1972

I was eleven when I heard of similar news about the canal in my hometown. The province’s Department of Highways had put forward a plan to drain the soon-to-be abandoned section of the Welland Canal through its namesake city and build in the channel a new high-speed highway to whisk people efficiently from the QEW to the frantic urban centre of metropolitan Port Colborne – a city that, even today, hardly warrants a 400-series highway. (No disrespect to the people of Port Colborne – I have two cousins there – but the town has only 20,000 people.)

At Queen’s Park, opponents of the Ministry of Transportation’s plans were skeptical. The residents in Welland were furious. As a kid, I was just confused. Like the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, Welland’s man-made waterway was the historical and spiritual heart of a city that owes its very existence to the canal. Why would anyone want to take that away?

Ottawa, 2018

While leading a walking tour of the locks at the base of Parliament Hill a few years ago, I was asked by a man from Thorold about which of the two canals is the older; the one we were touring or the one in his backyard. The answer is a bit convoluted. William Hamilton Merritt completed the Welland Canal in 1829; three years before the Rideau Canal opened. But that canal was almost entirely destroyed through the 1850s when the Province of Canada Board of Works (the predecessor of the same department that contemplated the Rideau’s fate, in 1910) gradually replaced that first canal with a wider one, with bigger locks; naturally using the path of the existing canal. (Part of historic Lock 5 is still there, but you have to blaze a trail through bush to get to it. The ruins sit underneath Highway 406.) Yet, against the odds (and, as we’ll see, the wishes of Canadian Pacific), the Rideau Canal remains today, and still in use, as it was nearly 200 years ago. The size of the locks is the same now as the day Colonel John By approved the paperwork for their construction. This makes the Rideau the oldest surviving canal in Ontario.

The current Welland Canal is its fourth, and largest, iteration. The Welland locks make the Rideau’s locks look like teacups. (The three continuous locks at Thorold – Locks 4, 5 and 6) are three times the length of all eight adjacent locks in Ottawa.) It’s fascinating to watch ocean-going ships climb what is essentially the engineered equivalent of Niagara Falls (11 km to the east) but still, the Welland Canal lacks the charm and the heritage of the Rideau Canal.

Mississauga, 2025

(I hope my relatives in Welland don’t read this.)

Ottawa, 1910

When he took over as CPR’s general manager in 1903, McNicoll went on a mission to correct the mistakes he felt Ottawa’s earliest railway had made when building their line into Ottawa; something that his 1910 plan intended to correct.

The earliest of these – the Ottawa & Prescott Railway (by 1910, it was CPR’s Sussex line) – chose a terminal near the mill complexes at New Edinburgh. This alignment secured a lucrative source of freight tonnage, but left passengers bound for central Ottawa well east of their destination; with a long horsecar connection back into town. Fifteen years later a second line into Ottawa – the Canada Central (CPR’s Ellwood line, in 1910) – established a terminal at LeBreton Flats. It was also a good source of freight traffic, but this time passengers were trapped well west of the city centre, and a horsecar ride into town.

Meanwhile, CPR’s competition – Grand Trunk – had already chosen a route into Ottawa, along the east side of the Rideau Canal, that brought its trains right into the heart of city; just a few blocks away from Parliament Hill. McNicoll could have considered the option of sharing GTR’s line, but that meant writing monthly rent cheques to the competition. The better plan, in McNicoll’s view, was to pay one flat fee to buy the Rideau Canal from the Dominion government and use its right-of-way into the city centre. Misleading tales of summertime cholera outbreaks from stagnant canal water, or ice jam-induced spring floods, or military obsolescence, or declining traffic were all part of McNicoll’s pitch to diss the canal and motivate the seller.

The canal path was necessary to get passengers into central Ottawa from a line CPR had built on its own, in 1898 (the M&O Line), to be the shortest, fastest way between Ottawa and Montreal. The proposed Rideau Canal connection would also be the fast way west, to Toronto, too. To link the nation’s capital to its two biggest cities (something GTR had already done), McNicoll needed the canal’s right-of-way, come hell or stagnant water.

Rochester, 1908

McNicoll’s plan to drain the Rideau Canal and encase it in a concrete straitjacket was monumental, but not unprecedented. CPR’s plan for Ottawa had an an eerie (if you’ll allow the bad pun) similarity to events taking place in Rochester, New York.

Construction began two years earlier on a project to direct the Erie Canal south of the city. In the meantime, even while the old canal through the city was still in use, Rochester’s city fathers were drafting plans to drain the soon-to-be disused section and convert it to a subway (sort of) to give the city’s streetcars – inbound from the suburbs – a car-free path downtown. (The original Erie Canal is older, although only by a few years, than either the Welland or Rideau.) Looking through editions of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle from that period, there seems to have been little opposition to removal of the historic canal. I guess it wasn’t really all that historic at the time. Heritage preservation wasn’t as strong an initiative in 1910 as it is today. Lift bridges, seemingly more often up than down (something I remember from my youth) delayed traffic, but residence, and D&C’s editor, seemed to welcome the canal’s end.

But Ottawa’s a different story.

Ottawa 1910

Opposition was strong here. That is to say that there was unity in Ottawa between residents, businesses and local politicians, to save the Rideau Canal. The position itself was weak.

The only case the community had, to stop CPR from moving ahead with its plan, was the cultural heritage defense. Long before Queen Victoria selected Ottawa as the capital of Canada, the Rideau Canal planted the seed that geminated into a city. It was seminal, it was scenic, it was serene. But by 1910, the Rideau Canal had become nearly useless.

CPR’s defense for its railway plan was that the Rideau Canal had outlived its purpose. McNicoll declared that public opposition to the closing of the Rideau Canal was “a matter of sentiment, not business.”

Frustratingly, McNicoll was right. Traffic had been on the decline on the Rideau Canal for over a decade. The Ottawa Journal (an opponent of CPR’s plan) commented on a report by the Department of Railways and Canals which seemed to state that there had been a “substantial increase” in marine traffic on the canal, and that passages in 1909 had been the highest in 15 years.

But that statement was a bit misleading, whether by choice or by ignorance. It’s true that traffic had been up on the “Ottawa District” of the the Department’s network, but that geographic district also included the tonnage stats for the Carillon Canal and Grenville Canal (the chain of locks and channels along the Ottawa River, eastward to Montreal) since all tonnage passing through these two canals, as well as the Rideau, north of Smith’s Falls, was reported to the Ottawa office of the Department of Customs and Excise. More than two-thirds of the district’s registered tonnage traveled through the Ottawa River canals; not the Rideau Canal.

Passenger traffic through Ottawa (Locks 1 to 8), Hartwells (Locks 9 and 10) and Hog’s Bank (Locks 11 and 12) in 1909 was down to 19,498 passages from a 1905 peak of 24,394.

It’s easy to play with the numbers, and McNicoll did. Annual traffic flow on the Rideau Canal typically, unpredictably, rose and fell frenetically over the years, like mercury in an Ottawa thermometer in springtime. Good harvests or bad on Ottawa Valley farms – alone of all other commodities shipped on the canal – could adjust the number of freight passages by integers, year by year. A busy year of road construction could send aggregates tonnage up that year, followed by a season with no tonnage at all, once the new roads projects were completed. Even in recent memory, a global pandemic slashed traffic on the recreational canal. And just when recovery seemed in sight, traffic flow was stalled by rising gas prices, which sent boaters looking for a cheaper pastime, in the meantime. Using Covid-era lingo, business on the Rideau Canal has always been ‘hardwired’ to the unpredictable economy around it. The numbers favoured CPR in 1910, but what of the future?

If the data was open to interpretation, and sudden change, McNicoll had stronger defenses. He claimed that the Rideau Canal no longer served any strategic need. This statement is true, but like the commercial traffic, McNicoll’s military claim is also a bit on the misleading side.

Bytown, 1826

McNicoll hesitated to note that the naval traffic that was supposedly down had, in fact, never been “up”. The Rideau Canal was not a vital link in Canada’s military defense strategy. Of course, one reason for that is the fact that the canal opened 18 years after Canada’s last war with the US. And if war were to flare up again, the possible quick capture of Kingston (the southern entrance into the canal) by the Americans would quickly turn the canal from a strategic defense for Canadians into an effective invasion route for Americans, with the canal’s other end being the primary target the invaders’ advance; Canada’s seat of government.

It wasn’t Britain’s might that Canada was looking for in building the Rideau Canal. They needed the army’s experience. The well-established chain of command of the British Army was essential to progress and completion of such a demanding project. The men of the Corps of Royal Engineers and the Royal Sappers & Miners had the skills to build a canal. Blasting through granite required expertise with explosives; which made the Royal Regiment of Artillery the right appointment for the task of building dams. And with nearly 250 years of empire on its CV, the project overseer – the British Ordnance Department – could shame amazon.com when it came to logistics. If the canal were to be built today, contractors with a wide array of logistical skills would make a bid for the project but the army got the Rideau Canal contract because there were no private contractors in Upper Canada in 1826. (A recent project to naturalize the former Cuyahoga Canal in Cleveland was undertaken by the United States Army Corps of Engineers because the army outbid the private competitors.)

Ottawa, 1910

Not that any of this history mattered to McNicoll. He hadn’t come to Ottawa to convince the locals. He needed to convince the politicians that destroying the Rideau Canal was good for the home field. The city would certainly feel the effects hardest, whichever way Parliament chose, but either way, the feds had the final decision. A wrong decision could make it the governing party’s Waterloo.

Waterloo, 1815

Wellington is a name associated with victory, but that same name proved to be McNicoll’s downfall.

Ottawa, 1910

If sending the last drops of Rideau Canal water down “The Wash” (today, the alignment of King Edward Avenue) and over the Rideau Falls wasn’t enough to raise concern, then digging a tunnel under Wellington Street from the Sappers’ Bridge to CPR’s existing station in Lebreton Flats raised a few eyebrows. This was the expensive chapter in McNicoll’s plan, and it seemed so unnecessary. If only McNicoll could let go of his contempt for Grand Trunk and share the station it was building across from (and along with) the Chateau Laurier, then the cost of the Wellington tunnel could have been avoided, and CPR’s passenger wouldn’t still be stuck in the outer reaches of civilization (Lebreton Flats) waiting for a streetcar connection to the Chateau Laurier.

If McNicoll had let go of the weak part of his plan, the rest of it might have come to pass. (McNicoll died six years later. His successor, Edward Beatty arranged to share GTR’s tracks east of the canal, and its central station in 1920.)

Utrecht, 1969

What would Ottawa be like today if CPR had had its way, and the Rideau Canal was no longer the cultural artery in a city with many historic veins? Utrechtites (or whatever you call people from Utrecht) asked that same question 50 years ago. Canals had been coursing the flat terrain of the Netherland centuries before the first one was built in Canada, but a canal in Utrecht was drained in 1969 to build an eight-lane highway through the centre of the city. After a generation of regret (and declining population in the once trendy Binnenstad district) the people of Utrecht decided they wanted their canal back.

It was a double-whammy defense for canal restoration in Utrecht. The Dutch love their heritage and they’ve grown to hate their highways. Voters demanded a new master plan for the city which (in addition to more cycling paths instead of roads) placed a focus on restoring the Catharijnesingel (the Dutch also love long words) and installing recreational amenities alongside the restored waterway. Conversion started in 2015 and was completed in 2020.

The Catharijnesingel canal started out 800 years earlier as a defensive moat at the perimeter of the old city, but was widened in small stages through the 1810s an ’20s. Like the Erie diversion around Rochester, the Catharijnesingel supplanted the Oudegracht (“old moat”) to the east, which ran through the centre of old Utrecht, but which had become too hemmed-in to be widened to meet the requirements of larger boats; like the original canal through Rochester. So, while Americans were building the first large canal on this continent, ancient Utrecht got a new canal and kept its old one as a scenic feature of the old downtown. Now that’s civic devotion to canals.

Ottawa, 2026?

If McNicoll had gotten his way in 1910, would support in Ottawa to restore the Rideau Canal be as strong today as it was in Utrecht, 20 years ago? I’m inclined to believe that Ottawa folk love the canal they have . . . because they have it. But experience tells me that they’d miss the railway (and mostly roadway) access that would have to go to bring the Rideau Canal back to life, so long after its 1910 demise. (Or, let's say “1920 demise”, given the amount of time it takes the government to decide anything . . . which was, incidentally, McNicoll’s biggest concern in 1910.) In my past walking tours, every time I mentioned the possibility of closing Colonel By Drive, parallel to the canal, to put back the railway tracks that were there up to 1966 (so that trains could reach the “re-repurposed” Grand Trunk station – currently the home of the Senate), the response from those on my tours usually ranged from cautious consideration to rabid rejection.

Unlike Shakespeare, who left you no doubt when his play was coming to an end by killing off all the characters, I’ll leave the conclusion of this story on the near-death of the Rideau Canal to you by asking you what I asked the people on my tours. Would you be willing to sacrifice Colonel By Drive to bring trains back into the city centre. And . . . if Canadian Pacific had succeeded in 1910, would you be willing to sacrifice the roads and rails that were put in its place to get back a long-forgotten canal?