Among the settlers who populated Bytown, many were francophones. By examining the stories of her own francophone ancestors, Sonja McKay reveals a window through which we obtain a glimpse of what life would have been like for many French-Canadians during that era.

Sonja McKay is a retired public servant and social policy analyst, an amateur genealogist, and member of the Historical Society of Ottawa.

Zéphérine Brunet, a French Canadian in Bytown, 1830s-1850s

Among the settlers who populated Bytown between 1826 and 1855, there were many francophones who came from what is now Quebec. Some of them were my ancestors. I will describe the experiences of a few of them in this article.

Many French-Canadians arrived in Bytown to work in the growing lumber industry in the 1840s and ‘50s. As well, some highly-educated French Canadians came to Bytown (e.g. physicians, lawyers, religious officials, business owners and their families). Lucien Brault’s 1941 in-depth thesis on the history of Ottawa recounts that by 1851, there were 2,056 French Canadians in Bytown, out of a total population of 7,760. Over 25% of the population were francophones.

We know too, that the land and waterways around Ottawa had already long supported Indigenous families and nations – notably the Algonquin Anishinabe nation on whose traditional lands Bytown emerged. Bytown was not a beginning for the Ottawa region, but it was the beginning of my personal family history here.

This article tells the stories some of my francophone ancestors and their friends who came to Bytown in the 1830s and ‘40s. A key figure is Zéphérine Brunet, my great-great-grandmother. In learning bits of information about her and her family, we can see a glimpse of what life was like for labouring French Canadians in those days.

A quest to learning about the origins of my grandpère, Adonias Robillard

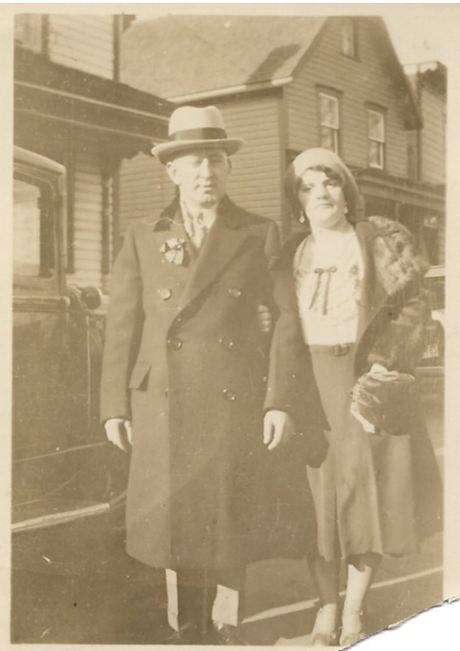

I never met my grandfather, Adonias Robillard, because he died before I was born. Adonias was born in 1893 in Ottawa, and he did metalworking until his death in 1955. My mother, Carmen, remembers him as a kind and loving father. Carmen grew up in a franco-Ontarian family in Eastview (now Vanier). Her mother Eva Létourneau was born near Québec City and migrated to Ottawa with her parents when her father obtained a civil service job in the federal government. The couple married in 1930. My family has few photos of Adonias – one was taken on his wedding day. It shows him dressed in his best outfit, probably standing outside his bride’s home on Friel Street in Lowertown Ottawa.

Figure 1: Adonias Robillard and Eva Létourneau, circa 1930. Photo courtesy Carmen McKay

Figure 1: Adonias Robillard and Eva Létourneau, circa 1930. Photo courtesy Carmen McKay

When I searched for more information about Adonias, I found that both of his parents were born in the Ottawa area (one in Gatineau) and all four of his grandparents were either born in Bytown or moved to the town before 1855.

Bytown in the 1830s was in a period of transition from the building of the Rideau Canal in 1826-32 towards becoming a booming lumber town. Between 1835 and the mid-1840s, it seems there were more people than jobs in the lumber industry, and consequently conflict. It’s said that the Shiner’s War between mainly French-Canadian and Irish lumber workers took place then. There was no police force and no jail. What could go wrong?

1830s: Zéphérine Brunet, her family and friends

The earliest of my great-great-grandparents to arrive in Bytown was Zéphérine Brunet. She moved here with her parents in the year 1835, or possibly a year or two earlier, when she was just six years old.

Zéphérine’s approximate year of arrival in Bytown is decipherable because of records of her siblings (and her own) dates of birth and places of birth. The eldest of 9 children were born in St. Eustache (just north-east of Montreal) where her parents had married. Zéphérine and others were born in La Petite Nation (which includes what are now the towns of Papineauville and Montebello on the north side of the Ottawa River). Zéphérine was born in the summer of 1828. Her youngest two brothers were born in Bytown – one in 1835, the last in 1840. So, they were in Bytown by 1835.

Zéphérine’s father, Janvier Brunet, is identified as a “journalier” or labourer in various documents. The family migrated following employment opportunities, with mother Amable and children making a lively home wherever they went. It’s possible Janvier worked mainly in Bytown (rather than away in a lumber shanty), perhaps in a lumber yard, or assisting a merchant in the ByWard market.

The Brunet family knew another family that came to Bytown around the same time – the Brûlés. Both families spent a few years living in La Petite Nation east of Bytown on the north shore of the Ottawa river, a region named in reference to the Indigenous people that already lived there. That region of la Petite Nation was just beginning to be settled by Europeans in the early 1800s. Similarly to Bytown in the 1820s, there was not yet a permanent church or priest assigned to the area. Missionaries would travel to the area every few months. In fact, Zéphérine was not baptized until five months after her birth, probably due to the family’s distance from a priest.

The Brunet and Brûlé families may have held land leases in La Petite Nation, but I found no evidence of this. Possibly they were employed by leaseholders to cut trees, clear rocks or till the soil. Perhaps, once the trees were sold, they moved on. For whatever reason, both the Brunet and Brûlé families moved to Bytown in the 1830s.

My family’s picture starts to become more clear in the 1840s as more records of births, marriages, and deaths appeared in my family tree.

The 1840s

In 1843, a law was passed called the Vesting Act. This made the acquisition of land and establishment of public amenities more feasible in Bytown, where previously the residential lots had been merely available for lease to townsfolk. This encouraged people to invest more in building solid homes.

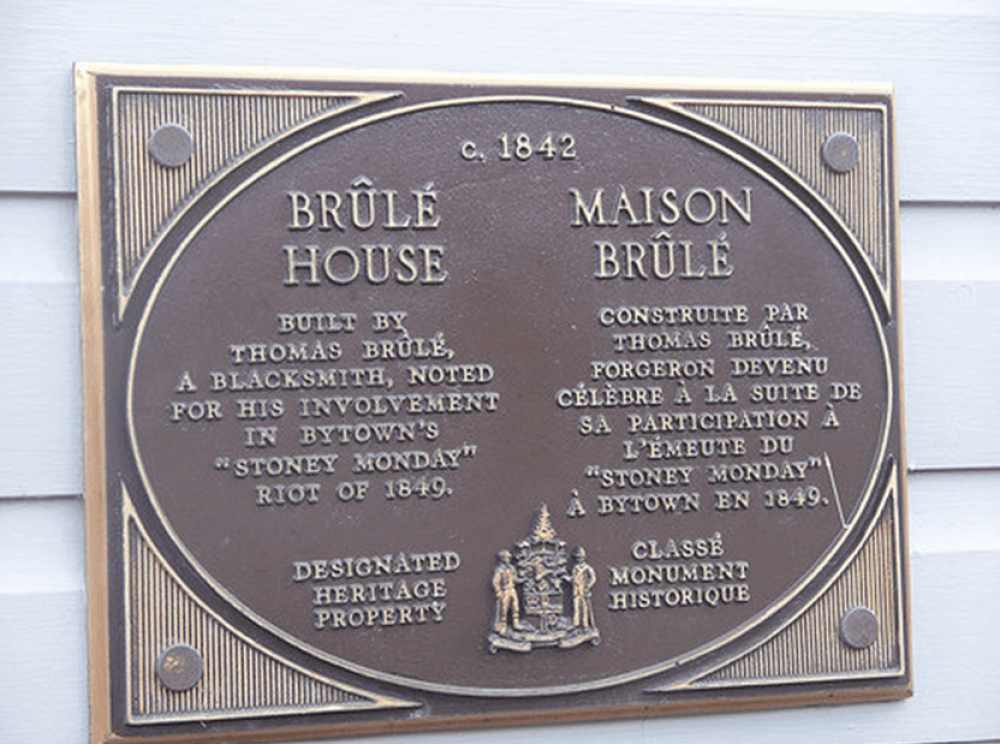

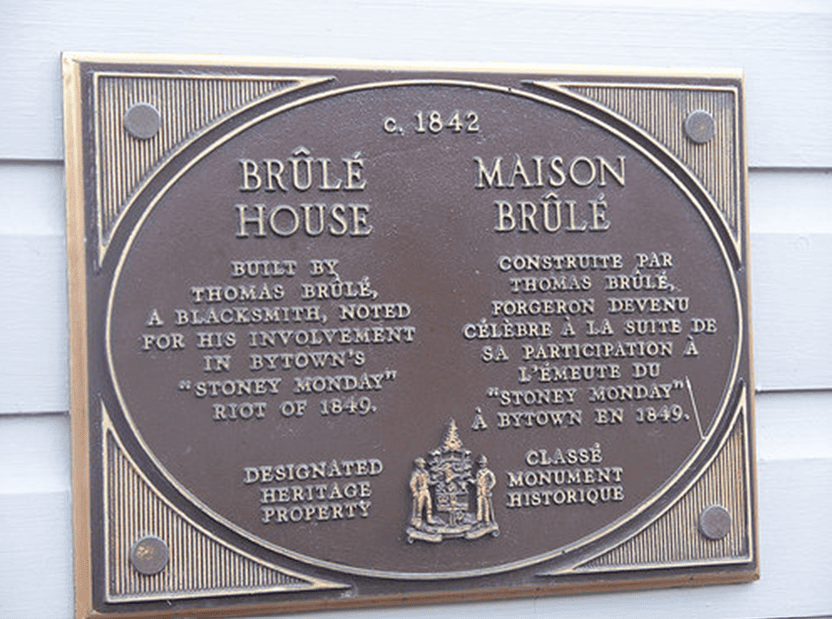

In this context, a still-standing heritage building on St. Patrick Street in Lowertown was built in approximately 1842 by Thomas Brûlé, a francophone blacksmith. Whether he began building it before or after the Vesting Act was passed, it seems likely he would have finished it as an owner of the lot, not just a tenant, as the building was solidly built enough to still stand today. Located at 288-290 St. Patrick Street, the building’s façade sits close to the street, and it has two front doors, indicating it formed two side-by-side homes. Behind the house one can glimpse a paved yard that once might have held a shed for a horse or a pig.

Figure 2: Brûlé House, 288-290 St. Patrick Street, 2024. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

Figure 2: Brûlé House, 288-290 St. Patrick Street, 2024. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

As the Brunet and Brûlé families’ children grew up, well, they got married. Zéphérine Brunet married Edouard Brûlé on July 1, 1846, in Bytown. Edouard was a brother of Thomas, and Thomas served as a witness. The marriage would have taken place in a wooden church, the precursor of today’s Notre Dame Cathedral. (Construction of the cathedral had begun in 1841, and the walls and roof were completed in 1846, but it was not quite ready to host services yet.) Edouard made a living in the logging industry, and may probably have spent significant time away from his wife. They had two daughters by 1849. As I’ll show below, it’s very likely they lived in the Brulé house with Thomas and his family.

As author Michael McBane described in his excellent 2022 book, Bytown 1847: Elisabeth Bruyère and the Irish Famine Refugees , Lowertown was a muddy, crowded place in the 1840s. Most homes were built of wood and the streets were not paved. There was no municipal plumbing or electricity. Many households kept animals such as horses and pigs in their yards, the latter to eat the leftover scraps and to be butchered for food. Cows were allowed to feed on local grass. Land not yet built on served as vegetable gardens in summer. Ice hauled from the river in winter was stored and sold in summer to cool food. Potable drinking water was scarce, and outbreaks of communicable diseases occurred.

Another event of the 1840s is worth noting here: Thomas Brûlé participated in the “Stoney Monday” riot in September of 1849, another violent episode in our city’s past. He and another man were charged with murdering the only person to die that day, but both were acquitted. It turned out no one saw who shot the victim, David Borthwick. The riot had erupted between people of different political views, which had coalesced into a dispute over whether to invite the Governor General to Bytown or not. I imagine the trouble Thomas found himself in worried his family greatly. In the end, he was free to resume his livelihood.

Figure 3: Plaque on Brûlé house 288-290 St. Patrick Street, Ottawa. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

Figure 3: Plaque on Brûlé house 288-290 St. Patrick Street, Ottawa. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

The 1850s – A husband’s death, a new marriage

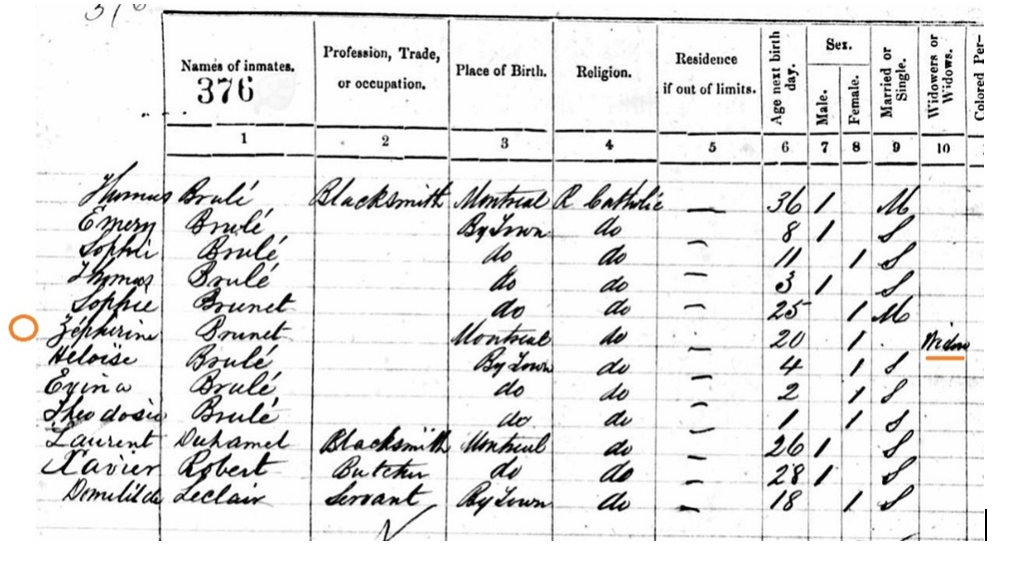

The 1851 census (taken in January 1852) shows that Zéphérine Brunet and her now three young children lived with Thomas Brûlé and his family -- see the orange circle in the census image, beside Zéphérine’s name, followed by her three daughters Heloise, Exina, and Theodosie. This residence must have been the 288-290 St. Patrick Street building, though no street addresses were given on the census. Sadly, Zéphérine was described as a widow. How could this be, I wondered?

Figure 4: Excerpt of 1851 Census showing those living with Thomas Brûlé. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

Figure 4: Excerpt of 1851 Census showing those living with Thomas Brûlé. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

Edouard had died a mere two months earlier, on November 14, 1851. A chilling note on the church register for his burial reads “tué par la chute d’un arbre” – Edouard was killed by a falling tree. It’s mainly because of this note that I assume Edouard worked in logging industry, and this was likely an accident in the forest while felling trees. The notation was written by father Damase Dandurand, a priest who arrived in Bytown in 1848 and who went on to serve the Roman Catholic community for the next 30 years. Thomas Brûlé was a witness to the ceremony.

This sad event had a silver lining, however, at least from my perspective. Edouard’s death paved the way for Zéphérine to remarry and have more children – one of whom became my great-grandmother Joséphine.

Zéphérine married her second husband, Eugène St. Jean, in Bytown on October 10, 1853. Eugène lived in Bytown, and he was from a town north of Montreal – St. Roch de l’Achigan. Again, the ceremony was performed by father Damase Dandurand, and Thomas Brûlé was a witness. The wedding likely took place inside the new Notre Dame cathedral, as it had been consecrated on September 4, 1853. Though the church’s decorate elements remained to be completed over the coming years, it already stood as solid beacon for the Roman Catholic community in the town.

Figure 5: Notre Dame Cathedral, Ottawa. Photo by Michel Rathwell, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 5: Notre Dame Cathedral, Ottawa. Photo by Michel Rathwell, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The couple had five children together – a son and four daughters. Their youngest child, Joséphine, grew up to become my great-grandmother (Adonias’ mother). By the 1860s, the family had moved to the northern side of the Gatineau River – just across the Ottawa river in Pointe-Gatineau. This is where Joséphine was born in 1866.

Not much is known about Eugène St. Jean other than the interesting fact that he studied classics at the College de l’Assomption between 1839 and 1841 in Quebec. I imagine from this that he may have worked as a clerk or some other occupation which required education. Unfortunately, he too passed away before 1871 when Zéphérine appears in the 1871 census as a widow in Pointe-Gatineau.

Later, Zéphérine moved back to the Ottawa side of the river, showing how closely connected the two sides of the river were (as they are to this day). She married a third time, and lived to the ripe old age of 96.

Conclusion

This story focussed on the Bytown days of my family’s history. As we know, Bytown was renamed Ottawa in 1855, and soon was appointed by Queen Victoria to become Canada’s capital city. My family’s Ottawa story continued until my mother met my father in Ottawa. While I was raised primarily in an English-speaking household, I am proud of my francophone heritage and happy to share some of it with readers.

My heart is filled with gratitude to know that these relatives, and other settlers, survived in Bytown through the help they gave each other. It saddens me to know they also grieved the early deaths of loved ones, but this was common for the time. This story demonstrates in a concrete way how families survived by cooperating and sharing resources, and moving to where there was work. We can glimpse through them, much about what life in Bytown was like for its francophone settlers.

References:

Brault, Lucien (1941). Ottawa: Capitale du Canada de sesorigines à nosjours . PhD Thesis presented to University of Ottawa.

Brault, Lucien (1946). Ottawa Old and New. Ottawa Historical Information Institute. Available at the Ottawa Public Library.

Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française.Vie française dans la capitale. A virtual museum website about Ottawa’s francophone history. Bilingual. https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/ Accessed 2026-02-03.

McBane, Michael (2022).Bytown 1847, Elisabeth Bruyère and the Irish Famine Refugees.Available in bookstores and at the Ottawa Public Library.

Notre Dame Cathedral. https://notredameottawa.com/history . Accessed 2026-02-02.