Michael McBane – Bytown 1847

Historian Michael McBane, author of Bytown 1847: Élisabeth Bruyère & the Irish Famine Refugees, re-tells this important story for the "Time Travelling with the Historical Society of Ottawa" HSO/Rogers TV series: https://www.historicalsocietyottawa.ca/resources/videos/time-travelling-with-michael-mcbane-bytown-1847

Michael is also author of John Egan: Pine & Politics in the Ottawa Valley.

Alastair Sweeny – “Ice Shintie” in Bytown

Alastair Sweeny, PhD, has written extensively about Thomas Mackay, including his 2022 book “Thomas Mackay: The Laird of Rideau Hall and the Founding of Ottawa”.

Other books authored by Alastair Sweeny include George-Étienne Cartier: A Biography, BlackBerry Planet, and Fire Along the Frontier: Great Battles of the War of 1812. Alastair is based in Ottawa and is a member of the Historical Society of Ottawa.

More on the story of the New Edinburgh Shintie Club medallions can be read in the excellent book “Win, Tie, or Wrangle: The Inside Story of the Old Ottawa Senators 1883-1935” by the late Paul Kitchen.

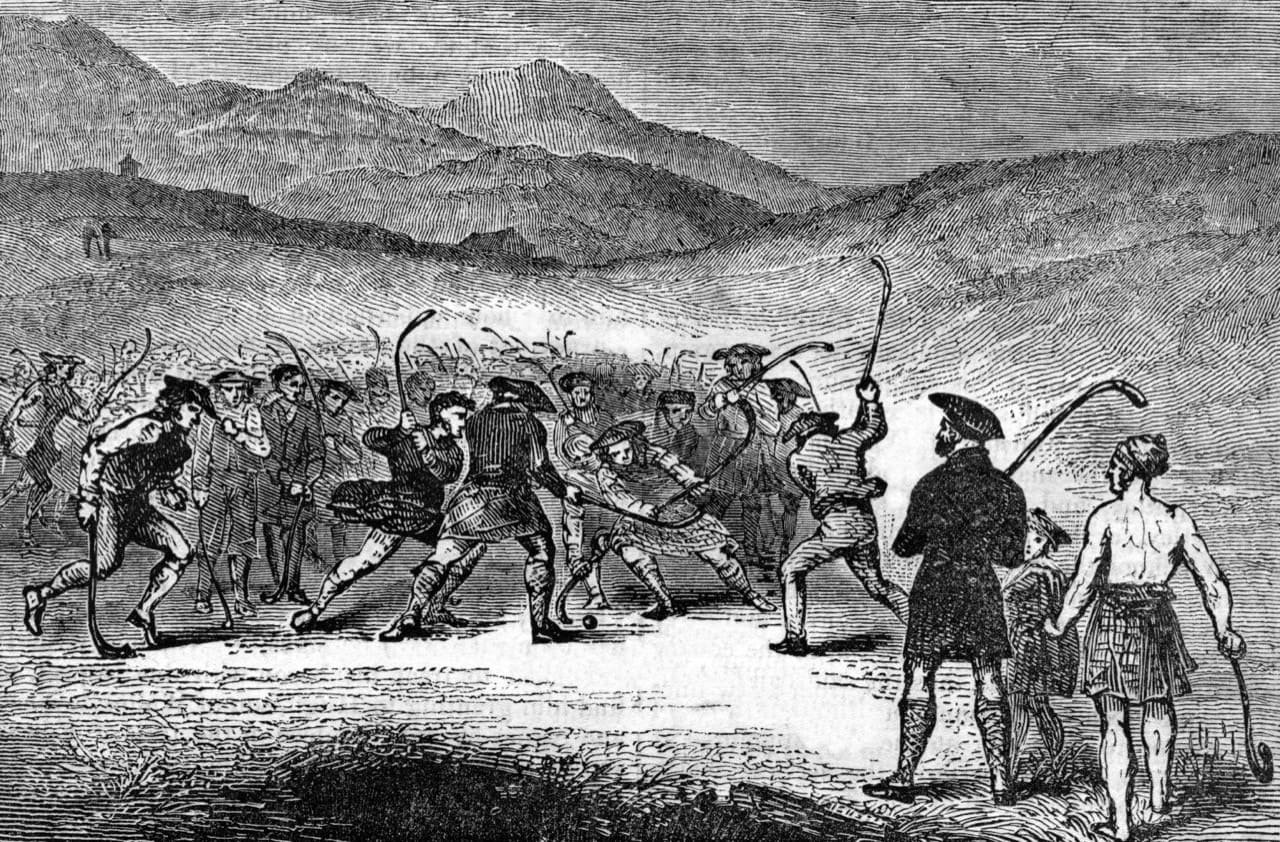

Scottish Shinty

Shinty (or shintie) is unique to Scotland and is regarded as the Scottish national sport. The game was supposedly introduced from Ireland 2000 years ago, along with Christianity, and was often played clan against clan.

Shinty is played with a cork ball covered in leather, that is slightly smaller than a tennis ball. Shinty sticks or camans were formerly similar to modern hockey sticks and are commonly confused by the same.

Shinty in the Highlands with Camans

Shinty in the Highlands with Camans

The earliest reference to shinty – or camanachd, prounounced ca-man-achd in Gaelic – comes from a Scottish text written on 1608:

A vehement frost continued from Martinmas [November 11] till the 20th of February. The sea froze so far as it ebbed, and many people went into ships upon ice and played at the chamiare [shinty] a mile within the sea mark. Many crossed over the Firth of Forth on the ice a mile above Alloa and Airth, to the great admiration of aged men, who had never seen the like in their days.

The keenness and duration of this frost was marked by the rare occurrence of a complete freezing of the Thames at London, where accordingly a fair was held upon the ice. In Scotland, rivers and springs were stopped; the young trees were killed, and birds and beasts perished in great numbers. Men, travelling on their affairs, suffered numbness and lassitude to a desperate degree. Their very joints were frozen; and unless they could readily reach shelter, their danger was very great. In the following spring, the fruit-trees shewed less growth than usual; and in many places the want of singing-birds was remarked.

The cold was caused by the eruption of the Peruvian volcano, Huaynaputina, which sent over 12 cubic miles of rock and ash into the atmosphere. This caused catastrophic weather events for a decade, including a Russian famine that killed two million.

Ice hockey evolved from Shinty after Highlanders and Scottish soldiers settled in Canada and took to playing shinty on ice for lack of a grass field in winter. Informal ice-hockey games in Canada are still referred to as shinny games.

In 1809, we find one of the very first documented mentions of a ball and stick game being played on the ice by skaters, in Perth, Scotland.

Scone Abbey

Scone Abbey

Close to Perth is Scone Abbey, where the Kings of Scotland were traditionally crowned for hundreds of years. From the 9th to the 15th Century, Perth was effectively the capital of Scotland. It was a primary residence for monarchs, and it was where the Royal Court was held. Royalty enhanced the early importance of Perth, and Royal burgh status was given to the city by King William the Lion, in the early 12th century.

In 1836, Scottish historian George Penny published Traditions of Perth, a collection of town anecdotes. One of his entries mentions games of shintie being played on Inch Island in the Tay River that runs through the town. Shintie – aka “shinty” – was an old Scottish form of field hockey or bandy, played with a ball and a caman - a shintie stick curved at one end, similar to a field hockey stick. Penny relates that Perth boys also played an ice version on skates:

The Shinty or Club used to be played in all weathers on the Inch; and frequently on the streets, by large assemblies of stout apprentices and boys. This game was also played on the ice by large parties, particularly by skaters, when there was usually a keen contest.

This explicit reference to skates is absent from the 1607-08 and 1740 references to games played on the ice.

It’s highly probable that one passionate player of the game was a seventeen year old Perth lad, Thomas Mackay, apprenticed to his father as a mason. After his father’s death at age 50, Thomas and his wife and mother emigrated to Canada, where he found plentiful masonry work in Montreal. In 1815 he won a contract to build the Lachine Canal, and in 1825, on the recommendation of Governor Lord Dalhousie, the Royal Engineers engaged him to build the Rideau Canal entry locks. In the 1840s, next to the Rideau Falls, he built a mill complex and village he called New Edinburgh, and a villa his daughter named Rideau Hall.

Mackay never forgot the game of his youth, and encouraged his friends and mill workers to take time out for winter play on the frozen Rideau River. On Christmas Day, 1852, Mackay, then age 60, hosted an ice shintie match between the New Edinburgh Scots against the Bytown Sassenachs (Englishmen). The Scots won 2-1 and the Laird of Rideau Hall awarded the Shintie Club winners this silver medal, now in the Bytown Museum in Ottawa.

Mackay’s Silver Shintie Medal, 1852 @Bytown Museum

Mackay’s Silver Shintie Medal, 1852 @Bytown Museum

Andrew King – Boats, Taverns, and Beer

Andrew King is an Ottawa artist and historian and author of the Ottawa Rewind blog.

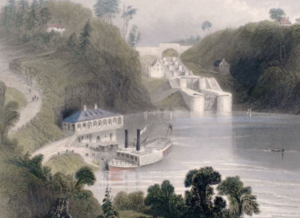

- Andrew recalls the steamships that once plied the Rideau Canal: The Lost Steamships of The Rideau Canal (May 22, 1832)

- Andrew unearths the Firth Tavern: Ottawa's First Pub (1819)

- Thirsty canal workers? Andrew combs through old maps to track down Bytown’s first brewery: Ottawa First Brewery (1831)

George & Iris Neville – Dr. A. C. Christie’s Travels 1830-1833

These transcriptions of Dr. Christie’s travel writings (1830-1833) along the Ottawa River and Rideau Canal provide a unique perspective into that early era.

From the HSO Bytown Pamphlet series:

107. Ottawa River Settlements in 1833 as described by Dr. Alexander J. Christie

Travel writings from 1833 by Dr. Alexander Christie. Reflecting on current events, Dr. Christie describes the settlements, land quality for agriculture, and lumbering and mineral resources of townships adjacent to the Ottawa River between Pointe-Fortune in the lower Ottawa River Valley and the McNab and Clarendon/Bristol settlements upriver. Transcriptions by George A. and Iris M. Neville.

072. Rideau Canal & Bytown Memoranda by Dr. A.J. Christie, Physician to the Rideau Canal Works

Memoranda of a journey from Kingston to Bytown made along the Route of the Rideau Canal, in February 1830. Written by Dr. A.J.Christie. Transcribed by George A. Neville & Iris M. Neville.

(Historical Language Advisory: Certain parts of the HSO pamphlet series may contain historical language and content that some may consider offensive, for example, language used to refer to racial, ethnic, and cultural groups. These items, their content and descriptions, reflect the time period in which they were created and the viewpoint of their author. The items are presented with their original text to ensure that attitudes and viewpoints are not erased from the record.)

Curtis Wolfe – William Tormey

Curtis Wolfe researches local history and heritage and his writings have been featured in Lowertown’s Community Newspaper The Echo.

Curtis uncovers the history of a local street: What’s in a name? Uncovering the namesake of Tormey Street.

The HSO 2026 Bytown200 Bicentennial Storytelling Challenge

Let’s hear your stories about Bytown and the Rideau Canal as we begin to mark 2026, the 200th anniversary of the beginning of both!

All contributions are welcome. Selected submissions will be shared on a special webpage on the HSO website for all to access, including educators. Eligible contributions can be submitted in a variety of formats, including written or audio/video.

We hope to also incorporate selected contributions into our many other platforms – such as our blog, the HSO Capital Chronicle newsletter, website articles and the Ottawa Stories sections and potentially our pamphlet series. All will be shared through our social media platforms well.

We welcome stories that pertain to the Rideau Canal or Bytown (1826-1855) or the Ottawa area’s history beforehand, as well as stories exploring the impact that the establishment of both had on the lives and livelihoods of Indigenous people.

We welcome new as well as updated or previously-published materials for submission. Contributors will allow HSO the right to publish their materials while also retaining the right to do so themselves.

Contact us to learn more: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We will also be happy to discuss any proposals for submissions you may have.

Have a look at our collection of stories: www.historicalsocietyottawa.ca/resources/bytown-200

Time Travelling with Michael McBane – “Bytown 1847”

Enjoy this episode of the HSO/Rogers TV series Time Travelling with Michael McBane.

Thomas Mackay & The Making of Ottawa

Alastair Sweeny, author of "Thomas Mackay, The Laird of Rideau Hall and the Founding of Ottawa" recounts the beginning of Bytown.

A Local Canvas: Paintings from the Bytown Museum Collection

Bytown Museum's Collections and Exhibitions Manager, Grant Vogl, gives a snapshot of the vast collection of art works held within the museum's vault.