Subject Area

The Ottawa River watershed, as traditionally claimed by the Algonquins at Golden Lake, was historically described as encompassing all of the land drained by the Ottawa River and the tributaries which flow into it, from Long Sault Rapids or Point d'Orignal on the Ottawa River (located below and above present day Hawkesbury) up as far as Lake Nipissing. This demarcation of the area does not include the Sulpician mission at Lake of Two Mountains (Oka).

It is unclear whether or not Lake Timiskaming was considered to be part of the lands traditionally claimed by the Algonquins and Nipissings. An examination of the hydrology of Ontario and Quebec indicates that the Ottawa River watershed includes the following tributaries on the Ontario side starting in the east: South Nation River, Rideau River, Mississippi River, Madawaska River, Bonnechere River, Indian River, Barron River, Petawawa River, Mattawa River and all of the small rivers, creeks, and lakes flowing into them.

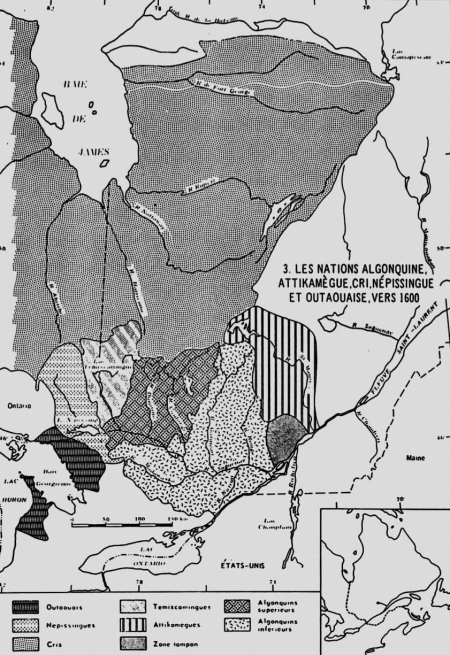

On the Quebec side of the Ottawa, the following major rivers are within the watershed, again starting in the east: Rivière Rouge, Rivière de la Petite Nation, Rivière Blanche, Rivière Lièvre, Rivière Gatineau, Rivière Coulonge, Rivière Noire, Lac Témiscamingue, Rivière des Outaouais, and the many small rivers, creeks, and lakes which flow into them. The map produced by the Ottawa River Planning and Regulation Board is the best source for identifying bodies of water within the Ottawa River system. [Map No. 32.]

Precontact

- archaeological evidence identifies occupation of the Ottawa Valley since the end of the last glacial period. In other words, the valley has been occupied for at least the last 10,000 years.

- since about 500 A.D. (about 1,500 years ago) the valley was occupied by a cultural complex identified by archaeologists as Algonquian. This generalized Algonquian cultural group stretched from Quebec to northern Saskatchewan; their material culture, and likely their socio-political culture, was distinct from the Iroquoian, Athabaskan, Plains, and Micmac/Maliseet cultures that surrounded them. Peoples identified in the historic period as Chippewa, Mississauga, Cree, Ojibway, Algonquin, and Montagnais are typically thought to have descended from the generalized Algonquian culture.

- these people lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering. Their socio-economic organization was characterized by seasonal migration within a defined geographic area. They were organized into small family based groups that exploited resources cooperatively. Typically, interrelated groups congregated annually, usually in summer, at resource-rich locations for social, religious, political, and economic activities.

Initial Contact

- the reader should be aware that the early historical records from which we gather our information about the aboriginal population were written by missionaries, explorers, and traders. While these records contain a wealth of useful information, they also reflect the ethnocentric bias, perception, and self-interest of Europeans and are not necessarily accurate depictions of the self-identity or actual relations between aboriginal groups.

- earliest contact within the subject area was made by Champlain in 1613. The Algonquins encountered along the river were already engaged as middlemen in the fur trade. The Ottawa River was an important trade route giving access to the upper Great Lakes and interior via Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay. In addition, the Ottawa led to an interior eastern waterway via Lake Timiskaming and the Rivière des Outaouais to the St. Maurice and Saguenay. Both eastern and western routes were important for avoiding the Iroquois and their allies along the St. Lawrence and lower great lakes.

- several different groups identified collectively as speaking the Algonquin language and/or being Algonquins were named as occupying the subject area. They were the Kitchesipirini (Allumette/Morrison's Island), Weskarini (Petite Nation, Lièvre, Rouge), Kinounchepirini (or Keinouche on the Ottawa below Allumette), Matouweskarini (Madawaska River), Ottagoutowuemin (Ottawa above Allumette), and Onontchataronon (or Iroquet on South Nation). Nipissings were located on the north shore of Lake Nipissing; some authors have indicated that they also occupied lands south of the lake.

- the Algonquins and Nipissings were allied with the Hurons and the French for carrying out fur trade and military operations to protect trade interests. Hurons used the Ottawa River for transporting trade goods. The Algonquins exacted tolls from all that used the waterway.

Iroquoian or Beaver Wars

- hostilities between Algonquins and Iroquoian peoples were recorded since at least 1570. They were rivals in the lucrative fur trade, the Algonquins being allied with the French, while the Iroquois were allied generally with the British. The St. Lawrence trade route had been effectively closed by the Iroquois until it was re-opened in i 609- 1610 with French assistance. Access to this route fluctuated with the state of warfare.

- the period from about 1640 to the end of the 17th century was a period of extensive warfare between Iroquois and Hurons, Algonquins and their allies. It was also a period of widespread epidemics during which large numbers of people died.

- the Ottawa River watershed was raided repeatedly and extensively by Iroquois, and Huronia was destroyed (1648-1650). During this period Algonquins, Nipissings and Hurons fled from the Iroquois and found refuge in various locations including French settlements at Trois Rivière, Quebec City, Sillery, and Montreal; others went to the Lake St. John region to the east. Some Nipissings reportedly travelled west to Lake Nipigon. There is some evidence that Algonquins did not completely abandon the Ottawa valley, but withdrew from the Ottawa River to the headwaters of its tributaries and remained in those interior locations until the end of the century. The period of dispersal is generally cited as 1650 to 1675. Ottawas used the Ottawa River for trade purposes from about 1654. During the last quarter of the 17th century, Algonquins were reported at numerous locations within the French sphere of influence.

- by the end of the 17th century, the Iroquois had been driven from southern Ontario by Ojibway speakers usually referred to as Mississaugas or Chippewas. Iroquois continued to occupy the eastern extremity of Ontario on a seasonal basis; the rest of the Ottawa River watershed on the Ontario side was occupied by unspecified Algonquians.

The 18th Century, the French period

- Algonquins and Nipissings were among those present when the French made peace with the Iroquois in 1701 in Montreal. The Algonquins and Nipissings, along with the other aboriginal nations, were considered independent allies by the French; they did not consider themselves subjects of the French King.

- in the period of 1712-1716 Algonquins were known to be living along the Gatineau River. Iroquoian occupation was limited to the area south ofthe St. Lawrence. Mississauga and Chippewa settlement was outside the Ottawa River watershed in southern and central Ontario.

- a 1740 map of Native people in Canada shows Nipissings north of Lake Nipissing, Algonquins on Rivière Lièvre, and Algonquins, Nipissings, and Mohawks at Lake of Two Mountains. There are no other aboriginal groups identified in the Ottawa River watershed. The closest Ojibway occupations in southern Ontario were at the Bay of Quinte and Georgian Bay. Algonquins were also shown outside the watershed at Trois-Rivières and there were Nipissings at Lake Nipigon.

- a 1752 report stated that Algonquins and Nipissings at Lake of Two Mountains came for a short time every year for trade purposes and left in the late summer for their hunting grounds far up the Ottawa River.

- evidence of non-Algonquin use ofthe watershed in this period was limited to suggestions that Algonquins and Nipissings congregating at Lake of Two Mountains allowed Iroquois from the mission to use their hunting grounds.

- prior to the conquest the area north of the Ottawa River was considered to be under French domination; while that south of the Ottawa was disputed territory. European settlement was limited to the shores of the St. Lawrence. Aside from a few fur trade posts, there was no European settlement up the Ottawa River or in the interior. As efforts to control the liquor trade in subsequent years indicated, the European powers had little effective control beyond the settlements.

Conquest and Royal Proclamation (1759-1763)

- the French were conquered by the British in 1759. Articles of Capitulation signed by the British guaranteed that the Indian allies of the French would be maintained in the lands they inhabited, be free from molestation, and have freedom of religion.

- one of the first traders to travel up the Ottawa River after the British conquest (1761) noted that the Algonquins at Lake of Two Mountains claimed all the land on the Ottawa as far as Lake Nipissing.

- in 1763 Sir William Johnson described the Algonquins and Nipissings (Arundacs) as being allied with the Six Nations and living at Lake of Two Mountains. He listed the Ottawas and Chippewas as residing in the territory from the Great Lakes to the Ottawa River. He also listed the Algonquins and Nipissings as being allied with both the Six Nations Confederacy and the Western Confederacy which included Chippewas, Ottawas, Hurons, etc. Johnson noted that he had very little contact with some of the aboriginal people. His previous experience was with Mohawks and other Iroquois allied with the British.

- the Royal Proclamation of 1763 specified that Indians should not be molested on their hunting grounds and that they could only sell their lands to the Crown after conferring in a public council specifically called for that purpose. Until their lands were ceded they could not be sold and patented. The terms of the Royal Proclamation form the basis of treaty and surrender policy and regulations in force to this day. TheAlgonquins had a copy of the Royal Proclamation that was endorsed by Sir John Johnson, who held the highest office in the Indian Department from 1782-1828.

Pre-confederation British Period

- in 1764 Carillon on the Ottawa, the eastern edge of the lands claimed by the Algonquins and Nipissings, was established as the post beyond which traders could not pass without a special license to trade in Indian country. Despite requests by the Algonquins, efforts on the part of the British to control the liquor trade past this post were ineffective.

- the earliest detailed petitions from the Algonquins and Nipissings date from 1772. They clearly and consistently described the Algonquin and Nipissing territory as encompassing both sides of the Ottawa River from Long Sault (above Carillon) to Lake Nipissing. They were actively using the area for hunting and trapping. These petitions were repeated in 1791, the year that Upper and Lower Canada were separated.

- the Quebec Act of 1774 extended the Boundaries of Quebec, which included the area under claim, and made provisions for the protection of all rights, titles, and possessions previous to the passing of the Act.

- the British were still administering their colony as Quebec in 1783 when the Crawford purchase and 1784 St. Regis and Oswegatchie purchases were made with Mississaugas (likely), Onondagas, and Mohawks. The Crawford purchase overlapped with the eastern extremity of the Algonquin claim area. The location of the Oswegatchie and St. Regis purchases is difficult to ascertain; there is no clear evidence that the purchases in fact encompassed any significant area within the Ottawa River watershed.

- all three purchases were taken in order that the British could settle Loyalists fleeing the United States, discharged soldiers, new settlers, and a group of Mohawks under Brant on the Indian lands. The Crown was keenly aware of the requirement to take a cession before opening up the lands for settlement although all three of these purchases were problematic in their execution and recording, they indicated that the crown believed the Indians treated with had a legitimate interest in the area. Around 1794 and 1795 there were protests from French mission Indians (likely including Mohawks from St. Regis and possibly Iroquois, Algonquins, and Nipissings from Lake of Two Mountains) because of settlers taking lands along the north shore of the St. Lawrence above Longueuil Seigneury. The settlements complained of would have included lands supposedly sold in 1783 and 1784.

- the Constitution Act of 1791 divided Quebec into the Provinces of Upper and Lower Canada. The Ottawa River was the division line, thus the lands claimed by the Algonquins and Nipissings fell under two separate administrations. The mission at Lake ofTwo Mountains was located in Lower Canada. The Indian Department officials acting on behalf of the Algonquins and Nipissings were stationed in LowerCanada. Thus, for the period 1791 to 1840, these people had no representative in Upper Canada.

- Nipissings and Algonquins issued leases and collected rents from islands in the Ottawa from 1802. Indian Department officials assisted them in collecting rents, enumerating squatters, valuing improvements, and regularizing leases. Ownership of the islands became the subject of petitions from about 1820. In 1839, the Crown declared that they had no right to lease the islands or collect rents. While the Crown considered the islands to be Crown land, the question of ownership of the islands continued into the twentieth century as some lessees continued to believe that the Department of Indian Affairs held the islands in trust for "Indians".

- by 1798 the Algonquins and Nipissings were complaining about lands along the Ottawa River being taken over by squatters without their consent or payment of compensation. These encroachments were interfering with their ability to support themselves. Complaints about squatters persisted throughout the pre-confederation period. In general, Crown authorities were unable or unwilling to prevent encroachments by settlers, lumbermen, white trappers, and traders.

- the Rideau Purchase of 1819/1822 took land from the Mississaugas up to the Ottawa River, indicating the Crown in Upper Canada recognized the Mississaugas as having a legitimate claim. Again the lands were taken in order to facilitate settlement. Algonquins and Nipissings protested the Rideau Purchase in 1836 as soon as they learned it included lands north of the height of land. Although repeated petitions were met with promises to investigate the purchase and consider payment of annuities to the Algonquins and Nipissings for this land, no action was taken. The Mississaugas of Alnwick, who were the descendants of the Rideau purchase signatories, continued to receive annuities until around the time of confederation. At that time, the annuities were capitalized and deposited in their trust account as assets of the band.

- during the period of about 1822 to 1830 there were numerous petitions and councils regarding the use of hunting grounds by various nations. Iroquois were reportedly encroaching on Algonquin/Nipissing territory, as were Abenaquis. These disputes were occurring throughout the British colony. Similar complaints were heard further east in the St. Maurice and Saguenay watershed. The Algonquins continued to assert their ownership of the Ottawa Valley. Têtes de Boule were reported to hunt and use trading posts within the Ottawa Valley on the Quebec side in this period. There are no known petitions citing them as trespassers. Mississaugas of Rice and Mud Lakes and the Crow River complained that Indians from Caughnawaga and Lake of Two Mountains were using their hunting grounds, however, they did not identify the area that they claimed was being encroached upon.

- at a council of Abenaquis, Algonquins, and Iroquois, the Abenaquis denied that Algonquins had any exclusive right to hunt on the north side of the St. Lawrence. The Crown ruled in 1822 that it could not appoint exclusive hunting territories for the various tribes, but favoured keeping the existing hunting grounds open to the Huron, Iroquois, Nipissing, and Algonquin. The conflict between aboriginal groups over hunting grounds was symptomatic of the pressures exerted on these groups byencroaching settlement, competition for resources, and disruption of aboriginal systems of policing boundaries. Several writers attested to the earlier systems under which tribal boundaries were strictly observed.

- The contact between Algonquins and Nipissings and European officials (church and state) was primarily through the mission at Lake of Two Mountains in Lower Canada. This location caused problems regarding their land claims in Upper Canada. It may also account for the seemingly inconsistent behaviour of the Crown, which was receiving a steady stream of petitions from Algonquins and Nipissings claiming lands which the Crown was obtaining from Mississaugas. Note, however, that the Algonquins and Nipissings did petition Upper Canada's highest authority, Sir J. Colbome, in 1835.

- Algonquins and Nipissings petitioning from Lake ofTwo Mountains acted together in economic and political matters. They wrote joint petitions, described their territory as a single undivided territory, and acted jointly to lease islands in the Ottawa. Dr. Black's detailed study of social relations at Lake of Two Mountains indicated that there was considerable intermarriage between the two groups and that individuals and families were often recorded as being Algonquin in one instance and Nipissing in another.

- Algonquin and Nipissing residency at Lake of Two Mountains was typically described as two months ofthe year (July and August), while most of the year was spent on thenhunting grounds. Only the very old and infirm stayed at the mission throughout the year. They came to the mission for various reasons including trading winter furs, collecting annual presents distributed by the British Crown, receiving religious instruction and education, and dealing with crown officials. Most correspondence, petitions, and councils involving representative chiefs took place during summer months.

- it is clear from petitions and government correspondence that unlike most groups in Upper Canada and many Lower Canada tribes, the Algonquins and Nipissings had no secured lands or revenues (with the exception of island rentals for a short period) and were dependent on traditional pursuits of hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering. They received annual presents until the mid-nineteenth century when the practice was ceased by the Crown. Part of the reason they had no secure lands or annuities was that the Algonquins and Nipissings had not entered into any treaties or taken part in any surrenders. This was acknowledged by the Crown.

- Indian Department officials familiar with the Algonquins and Nipissings at Lake of Two Mountains generally supported their claims to territory as described in their petitions. The officers most familiar with them were Resident Superintendent James Hughes, the interpreter Captain Ducharme, and Superintendent General of Indian Affairs Sir John Johnson.

- claims to specific parcels of the hunting grounds claimed by the Algonquins and Nipissings began in the 1830s. For example, Mackwa was located on the Bonnechere River, while Constant Pennecy was located on the Rideau.

- pre-confederation evidence of Mississauga use of the watershed include the following: the Crawford purchase in 1783, Rideau purchase in 1819/1822, and reports by Superintendent Anderson in 1837 that described the Mississaugas in Newcastle district as hunting up to the Ottawa River. More Mississauga claims were presented around the time of confederation.

- around 1836 officials begin indicating a willingness to assist the Algonquins and Nipissings in settling on unoccupied lands on the Ottawa River in the vicinity of Grand Calumet Portage and Isle aux Allumettes. Then, in June 1837, the Executive Council passed an order recommending that a tract of land be set aside for them in the rear of the surveyed townships along the Ottawa and that they be supported in their efforts to establish themselves. There was some indication that the lands intended for settlement were already occupied by squatters. No action was taken.

- Upper and Lower Canada were reunited by the Act of Union in 1840.

- beginning in the 1840s there was a proliferation of petitions and reports that indicated Algonquins and Nipissings were either moving away from Lake of Two Mountains or failing to visit the post on a yearly basis. Several factors were cited as accounting for the changes. The annual distribution of presents by the British was gradually withdrawn, at first children were cut off and then the presents ceased altogether. There was growing conflict between the seminarians and the Indian converts over the use of lands and resources at the mission. Increasingly, missionaries were establishing themselves in the interior, encouraging the people to focus activities at the new missions. At the same time, some groups came to Lake of Two Mountains for the first time in hope ofreceiving much needed material assistance from the seminarians or government officials.

- detailed information on Algonquin occupation of the watershed north of the Ottawa (Quebec side) begins in the late 1840s, when missionaries moved into the area. Previous to that time the information is scant Missionary records indicate there were numerous summer gathering places and family hunting areas in the large interior area of the watershed.

- requests for land for Algonquins in Bedford, Oso, and South Sherbrooke began in 1842. Numerous affidavits and declarations indicated that these people had used the land since at least 1817. A license of occupation was granted to the Bedford Algonquins in 1844 and was known to be in place throughout the remainder of that decade. During that period, Superintendent Anderson indicated that there were Mississaugas of Alnwick living with the Bedford Algonquins at this location. It is unknown when their relationship began or how long it endured. One family of Algonquins from that area was known to have moved to Dalhousie Township in the early 1850s. The location at Bedford was surrounded by timber activity and the Algonquins were constantly bothered by encroaching lumbermen.

- the Algonquins residing near Maniwaki (River Desert and Gatineau Rivers) had their reserve set aside under the 1851 statute, as did the people at Lake Timiskaming. The reserve at River Desert was set aside for the Algonquins, Nipissings, and Têtes deBoule hunting on the territory between the St. Maurice and Gatineau, who were described as principally residing at Lake of Two Mountains. Algonquins had been petitioning for lands they were using in this area for several years before the reserve was established.

- There were clearly other Algonquins in the area who were not living at the reserves or connected to the reserves. There were also frequent references to Têtes de Boule (Créé). Other settlements/areas included Grand Lac Victoria, Lac Barrière, Lac à la Truite, and Rivière Lièvre.

- in an 1858 report, Superintendent General of Indian Affairs Pennefather stated that the reserve at Maniwaki was given in compensation for the loss of their hunting grounds. It should be noted here that there was no cession of title or discussion with the Algonquins related to giving up any rights in exchange for the reserve.

- when the survey of the Ontario side of the watershed began there were scattered references to "Indians" throughout the watershed. The survey ofthe lands prompted people living around present day Golden Lake (Algona and Sebastopol Townships) and people on the Madawaska (Lawrence, Nightingale and Sabine Townships) to petition for the lands they used. Correspondence around these petitions indicate that the families were using the land since at least the early 1800s. A letter from the Crown Lands agent stated that their occupation was known to extend from at least 1778.

- in 1860 a petition from the Chippewas of Saugeen and the Chippewas of Lakes Simcoe and Huron stated that they supported the claim of their "brethren at Lake of Two Mountains" to a tract on the Ottawa which they had not ceded.

Confederation and the Late Nineteenth Century

- Mississaugas and Chippewas began petitioning for unceded land north of the 45th parallel in 1869. The crown studied their claim and noted that there was a large unceded tract north of that latitude. The lands that they described as being unceded included most of the tract claimed by the Algonquins and Nipissings. The discussion of the Chippewa and Mississauga claim in conjunction with the existence of a large unceded tract in Ontario became an on-going source of discussion between the province and the federal government.

- The Golden Lake reserve was purchased in 1873 for the use of local Algonquins. Families settled in the area of the reserve had been petitioning for more secure title to their lands since surveyors began moving through the area in the 1850s. The surrounding lands were being disposed of by free grant to white settlers; however, Indians were debarred by law from obtaining free grants. Just prior to confederation, the Crown agreed to sell the lands to the Algonquin families to be set aside as a reserve. No action was taken on the purchase until 1873 when the land was purchased from Ontario and vested in the Department of Indian Affairs in trust for the Algonquin Indians resident at or near Golden Lake.

- a license of occupation was allowed to people in Lawrence Township in 1866 (the year prior to confederation). Earlier correspondence had indicated use and occupation of this area near the headwaters of the York branch of the Madawaska. The license lapsed and continuous efforts by the Algonquin families to get secure tenure to another location in Lawrence, Nightingale, or Sabine Townships were finally abandoned when Ontario refused to allow lands to be set aside in 1897. Ontario's reluctance to permit an Algonquin settlement in the area was due to its proximity to Algonquin Park.

- Algonquin Park had been established in 1893. No consideration of the Indian interest in or use of the park had taken place before it was established and traditional activities within its boundaries were outlawed.

The Twentieth Century

- in 1898 the province prepared a brief which dismissed outstanding aboriginal claims against Ontario. This brief advanced the opinion that the reserve at Maniwaki "was meant to be in settlement and extinguishment of the claims of the Algonquins in respect of the lands of the Ottawa Valley." The authors of the brief supported this contention by referring to Pennefather's statements in 1858 (cited above) and added the concept of extinguishment of title to the notion of compensation. Again it should be noted that none of the prerequisites for extinguishment of title in fact took place. In addition, it should be noted that the reserve at Maniwaki was set aside specifically for those hunting between the St. Maurice and Gatineau Rivers, which clearly left the Algonquins on the Ontario side without a reserve.

- in general, off-reserve Algonquins and Nipissings were told to move to the three established reserves whenever they petitioned the government for assistance or land. A reserve had been established at Gibson, on Georgian Bay, to re-settle Indians from Lake of Two Mountains. Some Algonquins and Mohawks had moved there. Offreserve Algonquins were also encouraged to remove to Gibson from time to time. In 1903 many of the Gibson people returned to re-settle at Oka, St. Regis, and Caughnawaga; some may also have gone to Maniwaki. Of the 454 returning people, 185 (40%) were identified as Algonquins.

- the claims of the Mississaugas and Chippewas were reiterated early in the twentieth century. In general, it was the Mississaugas of Alnwick who claimed lands to the Ottawa River, Chippewas and other Mississauga bands generally only claimed to the height of land. An 1898 provincial brief concluded that the Algonquins' claim to the Ottawa Valley was superior to the claim of the Mississauga and Chippewas. The authors argued, however, that Ontario had no liability as title had been extinguished by setting aside of reserves in Quebec. The provincial and federal crowns considered these claims at several points, finally taking the Williams Treaties in 1923. The failure to consider the claims of the Algonquins is difficult to comprehend. Some evidence indicates that the 1916 Sinclair report and the investigations carried out by the commissioners in 1923 were based on incomplete evidence. On the other hand, some of the declarations from the early 1900s and some of the 1923 witnesses did indicate that their land extended only to the height of land separating the Ottawa River from Georgian Bay and Lake Ontario and that Algonquins claimed the other side. For amore complete discussion of this complex issue, refer to Vol. 3 - Purchases and Treaties in the Ottawa River Watershed; 1783. 1784,1819, and 1923.

- information collected on aboriginal use and occupancy of the Ottawa River watershed during the twentieth century shows some changes in patterns of use. St. Regis Mohawks are known to have trapped and hunted in the area between their reserve near Cornwall and Smiths Falls or Rideau Ferry on the Rideau River between 1924 and 1948. Most of the correspondence refers to trapping near Rideau Ferry.

- there is a great deal of correspondence regarding hunting and trapping by Golden Lake Algonquins and Algonquins living at other locations around the valley. This material is spread throughout the period and usually relates to hunting and trapping infractions and discussion of securing rights to hunt and trap. Most of the incidents occurred between the Mattawa and Rideau River. No occurrences or discussions of use in the eastern area of the watershed were located.

- the history of game infractions and protests is instructive in following the trends in enforcing hunting, fishing and trapping legislation. There were periods of leniency, in which regulations were not strictly enforced. The rationale for leniency was generally based on social welfare needs rather than on issues of aboriginal right. In fact, the concept of aboriginal right was not discussed. There was some discussion of treaty rights and a recognition that the Golden Lake Band was not under treaty. The federal crown was insistent that the Williams Treaties, although covering their traditional area, did not affect the Golden Lake Algonquins. They stated that it was only intended to impact on the rights of the Mississauga and Chippewa Bands, who actually signed the treaty.

- it is clear from the documentation that Golden Lake Algonquins were trapping and hunting in the Province of Quebec, particularly within the Grand Lac Victoria game reserve. Most of the correspondence regarding this practice dates from 1927 to 1938. The agent at Golden Lake issued letters of identification to band members stating that they were Algonquin Indians of Ontario. Pressures of settlement and provincial game regulation were often cited as impeding the ability of the Golden Lake people to support themselves.

- in the 1940s the Ottawa River system came under the joint regulation of Ontario and Quebec. A regulatory board now controls the flow of water through the system including the many dams and reservoirs on the upper Ottawa. Hooding has been a modem concern of the Quebec Algonquins who claim damages to lands and resources due to dams, storage reservoirs, and water diversion projects.

- the registered trapline system was established in the 1940s in Ontario. The Indian Affairs fur supervisor protested the distribution of traplines which, in his opinion, discriminated against the Golden Lake trappers. Due to his intervention some traplines were assigned to Algonquins.

- on the Quebec side of the Ottawa there were numerous reports, studies, and a great deal of correspondence regarding hunting and trapping areas and the dependence of the many off-reserve Algonquin communities on a traditional hunting and trapping economy. There is detailed discussion regarding the impact of settlement and resource development on the native economy. The changes in the size and purpose of the Grand Lac Victoria game reserve had a particular impact on the location of Algonquin settlements and the area of land they could use.

- additional Algonquin reserves and settlements were established in Quebec from the middle of the twentieth century. Lac Rapide was set aside for the Lac Barrière people and Lac Simon for the Lac Simon Band in 1941. Land at Winneway has been held for the Long Point Band under a leasing agreement since 1960. A reserve was set aside for the Kipawa Band in 1975.