Ottawa Holocaust Survivors’ Testimonials

Following World War II, approximately 40,000 Holocaust survivors resettled in Canada. Ottawa became home to many of those Holocaust survivors and hundreds of their descendants.

The Ottawa-based Centre for Holocaust Education and Scholarship invited 11 of those survivors to share their stories.

The Historical Society of Ottawa is honoured to link their testimonials to the HSO Memory Project:

Teddy Rogers: A Bear in War

My Trip to the Ottawa Regional Heritage Fair

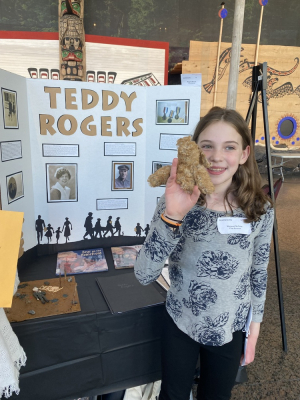

Hi, I’m Margaret. This year I took my heritage fair project to the Ottawa Regional Heritage Fair. My project for the Heritage Fair was about Teddy Rogers. Teddy Rogers is a teddy bear that a child gave to her father when he went to fight in WWI. A teacher at our school was the person who got First Avenue School involved. She was amazing and probably for a week before the Heritage Fair we practically lived in her class. I had such a great experience at the Canadian History Museum. It was held in the Grand Hall. The participating students ranged from grades 4 to 10. There were a variety of topics, but they had to be about Canadian history.

The Ottawa Regional Heritage Fair is an event where kids create, and present big projects typically done on a tri-fold display board about a Canadian topic. The topics vary from historical people and events, like Lucy Maud Montgomery or the Halifax Explosion, to people's families, or even a Canadian food like poutine. Immigration of different cultures is also a popular topic. Kids across Canada participate in heritage fairs.

At the fair, you get judged by two different judges. Both of my judges were very nice, they asked good questions, and it was more like just having a conversation about my project rather than presenting. One of them works at the Canadian War Museum and has held Teddy Rogers. Judges who were not judging me also came to my station. One of the people who came to my station is the director of the War Museum and the Museum of History. I had no idea when I gave her my presentation. But I found out later when they were giving out awards. After judging, we did our workshop which was looking around the museum. It was amazing. I walked around the museum with the teacher who organized the heritage fair at our school and some other students in my school. It was a lot of fun, and I learned a lot. Then we came back and there was an Indigenous drumming demonstration. Following that, they started the award ceremony. I wasn’t expecting to win anything because I’m only in grade six. But I did win something. I won the Canadian Museum of History award which means I got the highest overall mark. My sister and another team from my school both won awards. The Heritage Fair was such a fun experience, and you can see more details about it on the Ottawa Regional Heritage Fair site.

All About Teddy Rogers

My Heritage Fair project was on Teddy Rogers. Teddy was a teddy bear that Aileen Rogers gave to her dad when he went to fight in World War I where her dad Lawrence Browning Rogers sadly died at the Battle of Passchendaele. A soldier found Teddy in his pocket when he was getting Lawrence’s body. Teddy was then sent back to Canada. Many years later Teddy helped Aileen, who was now a nurse, greet kids coming over from England to escape the bombs during World War II. Teddy is now located at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, Ontario. In my project, I dove deeper into Teddy’s history with a paragraph just about Aileen, one just about her dad, the battle of Passchendaele and Teddy in World War II. I also gave information about Teddy nowadays. I shortened this version from my original project, so these are just the important facts.

Ten-year-old Aileen Rogers lived in east Farnham, Quebec and gave her father, Lawrence Browning Rogers, her favorite stuffed animal when he went to fight in World War l. Teddy is 12 centimeters tall, he is missing his eyes and has no legs. Teddy serves as a reminder of the cost of war. Lawrence Browning Rogers was born in Montreal on December 17, 1877. He was a frontline medic officer and stretcher carrier at the Battle of Passchendaele. Passchendaele was during World War I. Ethel Aileen Rogers was born in Montreal in 1905. When Aileen was 35, she was a nurse helping deliver children from England to escape WWII. On August 23, 1994, when Aileen was 93, she sadly died. A letter that Aileen’s brother Howard wrote to his father on September 8, 1917, sadly never got to his father. It was found in an old family suitcase by Roberta Innes. The letter that was not read was donated alongside Teddy to the Canadian War Museum.

In conclusion, Teddy is a two-time war veteran and shows how much Aileen loved her dad and how war can tear families apart. Whether it is someone dying, or people being sent away, there is no upside to war. If you would like to see Teddy in person, go to the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, Ontario. There are two books written about Teddy: A Bear in War and A Bear On The Homefront. These books were written by Lawrence Rogers Browning’s great-granddaughter, Stephanie Innes.

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

17 December 1939

“You must get on with the war, and in order to enable you to do so I now declare No.2 Service Flying Training School [SFTS] open,” said the Governor General, the Earl of Athlone, under bright blue skies at Uplands Airport just outside of Ottawa. With these words, the first intermediate flying school of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) was open for business. (No. 1 SFTS, located at Camp Borden opened three months later.) Eight Elementary Flying Training Schools (EFTS), located across the country, had already opened earlier that summer to provide basic flying skills to novice flyers.

The opening of No.2 SFTS came none too soon. Across the Atlantic that afternoon of 5 August 1940, the Battle of Britain was raging. With the RAF sorely stretched, trained pilots were desperately needed, both for the battle underway and for the successful future prosecution of the air war against the German Luftwaffe.

The genesis of the BCATP dated back to the mid-1930s when Britain, conscious of the growing Nazi threat, began to rebuild its armed forces, including its air service. In 1936, a Scottish-Canadian in the Royal Air Force (RAF), Group Captain Robert Leckie, wrote a memorandum to Arthur Tedder, then Director of Training at the British Air Ministry, suggesting Canada as an ideal location to train air crews. Canada was safe from enemy attack, and was close to the U.S. industrial heartland which could supply necessary aircraft engines and parts.

Additionally, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) had a close relationship with its British counterpart. As well, the RAF routinely recruited Canadians for both short-term and permanent positions. Moreover, during the latter years of World War I, flight training schools had been established in Canada by the Royal Flying Corps, the forerunner of the RAF.

When Prime Minister Mackenzie King got wind of the idea, he was conflicted. On the one hand, he was very protective of Canada’s new sovereignty. Following the ratification of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, Canada was no longer subordinate to Great Britain either domestically or internationally. Consequently, he could not support RAF bases in Canada. The Prime Minister was also conscious of how the presence of British bases in Canada might appear to Quebec voters. On the other hand, he thought that if Canada’s contribution to the coming war effort could be largely focused on training air crews in Canada, it might be possible to avoid both large-scale casualties and a repeat of the conscription crisis that had divided the country during the previous war.

Agreement was reached to increase the number of Canadian-trained pilots for the RAF, and steps were taken to develop a common RAF/RCAF flying syllabus among other things. However, Leckie’s concept of using Canada for RAF training bases was put on the backburner until the outbreak of war in September 1939 when Vincent Massey, Canada’s High Commissioner in London, met with his Australian counterpart, Stanley Bruce. Out of this meeting was born the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Who came up with idea is unclear as both men took credit for it. Regardless, they made a joint submission to the British authorities. Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, was enthusiastic, and made a personal appeal to Mackenzie King asking him to give the proposal his very urgent attention. Chamberlain expressed the view that the establishment of training bases in Canada safe from German attack would have a psychological impact on Germany equivalent to that produced by the entry of the United States into the previous war.

While Prime Minister King was initially upset that Massey had exceeded his authority, he quickly warmed to the idea…with conditions. Most importantly, Canadian sovereignty had to be respected. The flying schools would come under the authority of the Canadian government and would be administered by the RCAF. Consequently, trainees would be attached to the RCAF, would be subject to its jurisdiction, and would receive Canadian rates of pay. King also demanded that Britain agree to purchase Canadian wheat and that the BCATP would take priority over other Canadian war commitments. He also wanted Canadian pilots to be sent after graduation to RCAF squadrons in Britain as opposed to being subsumed into the RAF.

The Australians and Zealanders also had conditions of their own, importantly that costs be shared on the basis of population and that elementary flying instruction for their pilots would be conducted at home.

With these terms acceptable to the British, King sent his agreement in principle to Chamberlain at the end of September 1939 though his government continued to worry about the scale and cost of the venture.

Over the next three months, Canadian, British, Australian and New Zealand negotiators thrashed out the fine print of the accord and how the costs would be divided. It was hard going at times. But in the wee hours of 17 December 1939, Mackenzie King’s birthday, the Canadian prime minister signed the accord, followed by Lord Riverdale on behalf of the British government. As the Australian and New Zealander delegates had already left Ottawa, their governments’ signatures were appended later.

The agreement was officially titled “An Agreement to the Training of Pilots and Aircraft Crews in Canada and their Subsequent Service.” Later that day, in a radio address to the nation, King described the agreement as “a co-operative undertaking of great magnitude.” Charles Power, the Minister of National Defence, called it “the most grandiose single enterprise which Canada has ever embarked.” In a similar broadcast, Chamberlain, as requested by King, said that the BCATP would be more effective than any other kind of Canadian military co-operation. However, he added that the British Government would welcome “no less heartily” Canadian land forces in the theatre of conflict as soon as possible.

The cost of the agreement, which was to run until end-March 1943 unless otherwise extended, was placed at $607 million of which Canada’s share would be $353 million. The British contribution was set at $185 million, mainly in the form of airplanes and parts. The Australians and New Zealanders would contribute $40.2 million and $28.8 million, respectively.

Work immediately began to make the agreement a reality, with C.D. Howe, the Minister of Munitions and Supply, taking charge. Within days, offices were organized in temporary buildings in Ottawa, and contracts signed. By early spring 1940, air fields were being prepared, and the construction of hangers and other facilities underway.

Here in Ottawa, No. 2 SFTS, making use of an existing civilian airfield, practically sprang out of the ground overnight. In the space of just a few months, roughly forty buildings were constructed at the edge of Uplands field on what the Citizen described as a “desert waste of hillocks, tufted here and there with rank, saffron-coloured grass.”

The flying school boasted five double hangars to store aircraft, each 224 feet by 160 feet with 20-foot sliding doors. There were also buildings to house ambulances, a fire truck, refueling tankers, tractors, and other vehicles. There were quarters for 1,100 military and civilian personnel with canteens, messes, a recreation building, and a sports pavilion. As well, there were a supply depot, a guard house, a watch office, a drill hall, a ground instruction school, two bombing instruction schools, and a 34-bed hospital. Special storage tanks held 20,000 gallons of aviation fuel. There was also a depot for aerial bombs and machine gun ammunition. Located close to the main runway was an air-traffic control room. The landing facilities consisted of three tarmacked landing strips and three grass strips. Planes could land in every direction. There were also two subsidiary air fields located at Edwards and Pendleton, Ontario.

As the Ottawa training school was for intermediate training, pilots assigned to No.2 SFTS had already received flight instruction on Fleet or Tiger Moth aircraft, accumulating 40-50 hours of solo training. The maximum speed of these airplanes was 90-100 miles per hour. In Ottawa, the men graduated to Harvard training craft, capable of a top speed of more than 200 mph.

The Harvards, which were painted bright yellow, were dual-controlled, and were powered by 400hp Pratt & Whitney engines. The twelve planes stationed initially at Ottawa were built by the North American Aviation Company of California. More were in transit. Later, Harvards were constructed under licence by the Noorduyn Aircraft Company in Montreal.

On the other side of the Bowesville Road across from the flying school, the Ottawa Car and Aircraft Company was in the process of erecting a new plant for the construction of parts for the Avro Anson twin-engine aircraft to be used for training bomber pilots.

On opening day, 5 August 1940, the Governor General was accompanied by a distinguished entourage, including Prime Minister King, Defence Minister Ralston, Air Minister Power, Air Vice Marshall Breadner, and Honorary Air Marshall W.A. (Billy) Bishop, VC. The twelve, yellow Harvard trainers were lined up in front of the hangars. In front of the aircraft was an honour guard standing at attention to take the salute of Earl Athlone. A RCAF band from Trenton played Land of Hope and Glory. After No.2 SFTS was declared open, the Harvard trainers were flown in various formations to the delight of the crowds there to witness the historic event.

In July 1941, a Warner Brothers crew from Hollywood filmed part of the feature movie Captains of the Clouds, starring James Cagney, at Uplands airfield. Billy Bishop played a cameo role in a “wings ceremony,” where actual pilots received their wings in a stirring graduation ceremony. You can see a preview of the movie on YouTube : Captains of the Clouds.

The BCATP was a huge success, training roughly 50 per cent of all Commonwealth airmen during the war. In addition to Canadian, British, Australian and New Zealand personnel, men from many other Allied countries received their flight training in BCATP schools, including Norwegians, Poles, Belgians, Free French, Czechs and Americans. In a 1943 congratulatory letter to prime minister King. US President Roosevelt called Canada “the aerodrome of democracy.” (As an interesting sidebar to history, Lester B. Pearson, then the number two person at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, was the person who coined the phrase—an allusion to Roosevelt naming the US the “arsenal of democracy” in a late 1940 speech. Breaking diplomatic protocol, the White House staff had contacted the Canadian embassy and had asked Pearson to help draft the latter.)

With an Allied victory on the horizon, the program started to be wound down in late 1944 and was terminated at the end of March 1945. During the BCATP’s time in operation, more than 131,553 aircrew graduated from 105 flight schools of various description at a cost of $2.23 billion (roughly $35 billion in today’s money). Of this amount, Canada paid $1.6 billion ($25 billion). While the cost was considerable, victory in the air was made possible by the BCATP.

In 1949, representatives from all countries that had participated in the BCATP paraded at RCAF Station Trenton to witness the unveiling of a set of wrought-iron gates given to Canada by the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, as a permanent memorial and a symbol of Commonwealth friendship and unity.

Sources:

Dunmore, Spencer, 1994. Wings for Victory, McClelland & Stewart, Inc. Toronto.

Evening Citizen, 1939. “Four Govts. Are ‘Well Pleased’ With Air Pact,” 19 December.

——————-, 1939. “Gives Further Details Of Air Training Plans,” 19 December.

——————-, 1940. “Governor-General Opens Empire Training School At Uplands Field,” 6 August.

——————, 1940. “Crowds Are Thrilled By Formation Flying,” 6 August.

Hatch, F. J., 1983. Aerodrome of Democracy: Canada and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, 1939-1945, Department of National Defence, Directorate of History, Monograph Series No. 1.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa at War

3 September 1939

It was the Labour Day weekend, the last long weekend of the summer. But, instead of sleeping late or basking in the sun, Canadians were huddled around their radios, anxiously listening to news coming out of London. Shortly after 6am in Ottawa (11am London time) on Sunday, 3 September, 1939, Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, announced over the wireless that Great Britain was at war with Germany. The ultimatum that the British ambassador had delivered to the Reich’s Foreign Ministry in response to the German invasion of Poland had gone unanswered.

The news was not unexpected. For weeks the martial drumbeat had grown louder. With Germany and the Soviet Union signing a non-aggression pact in mid-August, there was nothing stopping the Nazis from attacking Poland. With a swift victory almost assured over the antiquated Polish army, Germany no longer risked a two-front war should Britain and France honour their pledge to support Poland. At the beginning of September, German forces entered Poland.

Unlike twenty-five years earlier, there were no shouts of joy and applause at the British declaration of war. Ottawa took the news somberly. Later that Sabbath morning, families went to church to pray for divine guidance for their leaders and protection for their families and friends in the perilous times ahead. In the early afternoon, families again gathered around the radios, this time to hear the King say: “I now call my people at home and my peoples across the seas who will make our cause their own. I ask them to stand calm and firm and united in this time of trial.” The Citizen reported that people wept hearing him speak. “It was the message of a beloved sovereign to a people with whom he and his Queen had mingled freely but a few short months ago [the 1939 Royal Visit] …It was as if His Majesty in truth had crossed the threshold of every Canadian home to bid them his good cheer in the extremity of the hour.”

Prime Minister Mackenzie King was awoken early with the news of Britain’s declaration of war. He hurried from Kingsmere, his country estate in the Gatineau Hills, to Ottawa for a 10 o’clock emergency Cabinet meeting in the Privy Council Chamber in the East Block on Parliament Hill. Meanwhile, instead of the usual Sunday quiet, Sparks Street buzzed with excitement as hundreds of anxious people milled about in front of the Citizen’s office waiting for the latest news bulletins to be posted. Extra police were laid on to control the crowd. Over that long weekend, Ottawa troops were mobilized with gunners moving into Lansdowne Park. Guards appeared on all public utilities and local dairy plants to prevent possible sabotage. Placards went up across the city saying men of military age were needed. The Cameron Highlanders announced that men should report to the Cartier Drill Hall at 9am on the Monday morning. The drum and bugle band of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps marched through Ottawa streets, with placards saying “Recruits wanted for the RCASC, mechanics, tinsmiths, coppersmiths, clerks, turners.”

When Mackenzie King left the Cabinet meeting around 2pm Sunday afternoon, the large crowd waiting for him outside the East Block cheered. The Prime Minister doffed his hat in acknowledgement and then paused for an official photograph to be taken by the Government Motion Picture Bureau for posterity. At 5.30pm, Mackenzie King spoke to the nation from the CBC broadcasting studio in the Château Laurier Hotel. Justice Minister Lapointe subsequently spoke in French. Mackenzie King promised that Canada would co-operate fully with the Motherland and urged Canadians to “unite in a national effort.” He added that “There is no home in Canada, no family and no individual whose fortunes and freedom are not bound up in the present struggle.” Parliament would debate the situation in Europe the following Thursday (7 September).

While both major Ottawa newspapers considered Canada to be at war, the country was actually in a strange limbo, neither officially at war nor really at peace. Since the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, Canada was an autonomous Dominion within the British Empire. Consequently, unlike in 1914, a declaration of war by Britain did not automatically mean Canada was at war. Although both Australia and New Zealand had followed with their own declarations of war immediately after that of Britain, Mackenzie King held back awaiting the Parliamentary debate. The government was making a constitutional statement, underscoring Canadian autonomy. It also mattered practically. While the United States had immediately stopped all deliveries of arms to Britain (and Germany) due to its “Neutrality Act,” which forbade military sales to warring countries, it considered Canada to be neutral, thus allowing arms sales and deliveries to continue.

Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings of Ottawa, First Canadian to die in World War II, 3 September 1939. His brother, W.O.2 Kenneth Cummings, was to die piloting a bomber over enemy territory in 1944. Ottawa Citizen, 6 September 1939.At the German Consulate located in the Victoria Building on Wellington Street, it was “business as usual” though most likely the German diplomats were busy destroying confidential documents in preparation for an imminent departure. Dr. Erich Windels, the German Consul General who had been in Ottawa since 1937, had received no instructions from the Department of External Affairs to leave the country. Guards were, however, posted at the Victoria Building and at 407 Wilbrod Street in Sandy Hill, the home of Dr. and Mrs Windels, a short walk away from Laurier House, the downtown home of their friend, the Prime Minister.

Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings of Ottawa, First Canadian to die in World War II, 3 September 1939. His brother, W.O.2 Kenneth Cummings, was to die piloting a bomber over enemy territory in 1944. Ottawa Citizen, 6 September 1939.At the German Consulate located in the Victoria Building on Wellington Street, it was “business as usual” though most likely the German diplomats were busy destroying confidential documents in preparation for an imminent departure. Dr. Erich Windels, the German Consul General who had been in Ottawa since 1937, had received no instructions from the Department of External Affairs to leave the country. Guards were, however, posted at the Victoria Building and at 407 Wilbrod Street in Sandy Hill, the home of Dr. and Mrs Windels, a short walk away from Laurier House, the downtown home of their friend, the Prime Minister.

Even before Mackenzie King had spoken that evening to Canadians, Canada, and Ottawa specifically, had already sustained their first wartime casualties. Four hours after Britain’s declaration of war, RAF Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings, the son of Mr and Mrs James Cummings of 46 Spadina Avenue in Ottawa, died, along with his Scottish gunner, in an airplane accident. Based at the RAF base in Evanton, Scotland, Cummings’ Westland Wallace biplane crashed into a hillside in thick fog. Cummings was the first Canadian to die in the War. His family received the grim news the following day. Cummings, age 24, had enlisted in the RAF in 1938. He had attended Glebe Collegiate and had been a member of Parkdale United Church. His father was the superintendent of the transformer and meter department of the Ottawa Electric Company.

Just a few hours later, a German U-boat deliberately sank the SS Athenia, a 526-foot, 13,500-ton passenger liner—the first British ship lost in the war. The liner, owned by the Donaldson Atlantic Line, had left Glasgow for Montreal, with a stop in Liverpool, on 1 September, two days before the outbreak of war. On board were 1,103 passengers and 315 crew members, of whom 469 were Canadians and another 311 Americans who were trying to get back home before hostilities began. Approximately twenty-one of the Canadians either came from Ottawa or had close relatives in Ottawa. Also on board were 500 Jewish refugees as well as 72 UK residents, plus a medley of citizens from other countries. Twenty-eight German and six Austrian citizens were on the liner.

At roughly 7.30pm in the evening of 3 September, local time (2.30pm Ottawa time), the ship, located off the western coast of Scotland, two hundred miles north of Ireland, was torpedoed by U-30 under the command of Oberleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp. As the ship began to settle into the water, the submarine came to the surface and fired two shells at the stricken ocean liner. While there was ample time for the ship’s lifeboats to get away, there were many casualties, in part due to accidents during the rescue by two British destroyers, a Swedish yacht, the Southern Cross, a Norwegian tanker, the Knute Nelson, and an American freighter, the City of Flint. In total, 98 passengers and nineteen crew members died, including 54 Canadians and 28 Americans. Most survivors were brought into Glasgow in Scotland and Galway in Ireland. The City of Flint disembarked the people it had rescued in Halifax.

Fritz-Julius Lemp, commander of U-30 which sank the SS Athenia. Lemp drowned in May 1941 when his later ship U-100 was capture intact off of Iceland, its scuttling charges having failed to detonate. On board was an Enigma machine and code book which were used at Bletchley Park to decode top secret Nazi signals. U-boat.net.The sinking of the unarmed Athenia was considered a war crime as the U-boat commander had not given the passengers and crew an opportunity to leave the ship. As well, when he realized that he had fired upon a passenger liner in error, he didn’t stay to help the survivors, but instead swore his crew to secrecy. Later, fearful that the loss of American lives might bring the United States into the war, the Nazi high command ordered Lemp to falsify his log. The Nazi newspaper Volkischer Beobacher blamed the sinking on Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. While nobody believed that tale, the real story of the sinking of the Athenia wasn’t revealed until the Nuremburg trials after the war.

Fritz-Julius Lemp, commander of U-30 which sank the SS Athenia. Lemp drowned in May 1941 when his later ship U-100 was capture intact off of Iceland, its scuttling charges having failed to detonate. On board was an Enigma machine and code book which were used at Bletchley Park to decode top secret Nazi signals. U-boat.net.The sinking of the unarmed Athenia was considered a war crime as the U-boat commander had not given the passengers and crew an opportunity to leave the ship. As well, when he realized that he had fired upon a passenger liner in error, he didn’t stay to help the survivors, but instead swore his crew to secrecy. Later, fearful that the loss of American lives might bring the United States into the war, the Nazi high command ordered Lemp to falsify his log. The Nazi newspaper Volkischer Beobacher blamed the sinking on Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. While nobody believed that tale, the real story of the sinking of the Athenia wasn’t revealed until the Nuremburg trials after the war.

Over the next several days, anxious Ottawa residents repeatedly called the Citizen for any news of loved ones who had been on the Athenia. For the most part the news was positive as one by one, the rescued Ottawa people were reported safe, mostly from Glasgow and Greenock in Scotland or Galway in Ireland. These included D. George Woollcombe, the former head master of Ashbury College, Miss Jean Craik, a young business college student who resided at 471 MacLeod Street, and Miss Mary Carol of 34 Noel Street, an employee at Ogilvie’s Department Store. Mr. James Ward of the Public Works Department also received word that his wife and 12-year old son, James Jr. were safe in Galway, Ireland. Thomas Graham of 224 Primrose Street who had joined the crew of the Athenia two weeks earlier as a cook was also safe on dry land.

Jean Craik was among the first Ottawa survivors to return home. Arriving shortly before midnight on the CNR train from Halifax with two other survivors eleven days after the Athenia was torpedoed, Craik recounted a harrowing tale. She had been on deck when the ship had been torpedoed and sailors started shouting for everybody to abandon ship. On her lifeboat were 56 mostly women and children and two sailors. She sat in the stern of the lifeboat where she was given the job of holding flares. A sailor named Kammin gave her his lifebelt, an act of heroism that saved her life and lost his. In heavy seas, her lifeboat capsized. Kammin perished. Many drowned in front of her, including a mother and a baby. Craik floated in the water for six hours before the Southern Cross rescued her. Of the 56 people who made it onto the lifeboat, roughly half lost their lives through drowning. The Southern Cross transferred Craik and other survivors to the City of Flint, who took them to Halifax. There, the Red Cross gave Craik a tooth brush, tooth paste, cold cream and a pair of silk stockings. One of the first things she did in Halifax was have a hot bath. Although she had lost all her possessions, Craik somehow managed to keep her purse which she had tied to herself. In it was one traveller’s cheque which she used to buy new clothes.

All the news was not good, however. Mr. F.H. Blair of Montreal, the uncle of Miss A.E. Brown of 415 Elgin Street, lost his life. He had given his life jacket to a woman, and subsequently drowned.

Canada joined Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand and other members of the Empire in the war against Nazi Germany on 10 September. After the Parliamentary debate, Canadian High Commissioner to London, Vincent Massey, received a cable from Ottawa recommending to King George that as King of Canada he approve Canada’s declaration of war on Germany. Massey transcribed the cable’s contents onto two ordinary sheets of foolscap paper which he took to Buckingham Palace. The King appended his signature “Approved George R.I.” Canada was officially at war.

Sources:

Boswell, Randy, 2012. “Memorial unveiled to first Canadian pilot to die in WWII,” Edmonton Journal, 6 September.

Bregha, François, 2019. “Australia House,” History of Sandy Hill, https://www.ash-acs.ca/history/australia-house/.

British Home Child Group International, 2019. “The Athenia,” http://britishhomechild.com/the-athenia/.2012.

Kemble Mike, 2013. “SS Athenia,” Merchant Navy in World War II, http://www.39-45war.com/athenia.html.

Ottawa Citizen, 1939. “Most Ottawa Folk Philosophical, But Ready To Do Duty,” 1 September.

——————, 1939. “Crowds Throng Citizen Bulletins,” 1 September.

——————, 1939. “Gunners Will Move To Lansdowne Pk For Training Duty,” 2 September.

——————, 1939. “Liner Athenia, Bound For Canada, Torpedoed, Britain And France Now At War With Germany,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Proclamation Declaring Great Britain At War Isued By Chamberlain,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “His Majesty’s Address To People Of British Empire,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “German Consulate Staff Here Ready For Word To Leave,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Crowd Cheers And Applauds Mr. King.” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Every Home In Canada Affected By Struggle Declares Prime Minister,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Effective Co-operation,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Fateful News Accepted With Determined Resignation,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “The Call To United Action,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Young Men Besiege Ottawa Recruiting Offices To Enlist,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Ellard Cummings, Ottawa Airman, Is Killed In Scotland, 5 September.

—————– 1939. “Report 3 More Ottawa People Rescued At Sea,” 6 September.

—————–, 1939. “Announce 125 Still Missing From Athenia,” 6 September.

—————–, 1939. “Report Many Ottawans Among Athenia Rescued,” 6 September.

—————–, 1939. “Says Indivisibility Of Crown Theory Disproved By War,” 11 September.

—————–, 1944. “Kenneth Cummings Of Air Force Is Reported Missing,” 22 March.

Ottawa Journal, 1939. “Ottawa Girl Vividly Describes Sinking of Athenia,” 15 September.

Uboat.net 2019. “The Men – U-boat Commanders,” https://uboat.net/men/lemp.htm.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Rib

4 August 1914

On the night of 4 August 1914, a slender, athletic, 21-year old man know as “Rib” took the night train from Ottawa to New York, never to return. That afternoon, he had been playing tennis with three friends at the Rideau Club when he received word that Great Britain had declared war on Germany which meant that Canada was also at war. Being a German national, Rib, along with other citizens of hostile countries including the Austrian chef at the Château Laurier, had four days to settle their affairs and leave the country, or be interned. Rib made a few hurried telephone calls, packed his bag, and dined with friends at the Chateau Laurier before catching his train. So quick was his departure that he had to borrow $10 from James Sherwood, the son of Col. Sir Arthur Percy Sherwood, Commissioner of the Dominion Police Force. Rib was sorry to leave. More than thirty years later, shortly before his death, he commented that if the war hadn’t come along, he might have never had left Ottawa. There, he had been “indescribably happy.”

Rib first arrived in Canada with his big brother Lothar in 1910. In an age before passports and visas, Rib, just 17 years old, quickly found employment. He worked for a time at a Molson’s Bank branch as a clerk in Montreal, before being employed by an engineering firm rebuilding the Quebec Bridge that had tragically collapsed in 1907. This was followed by a stint on a railway as a car checker, and a job as a logger in British Columbia. After briefly returning to Germany to convalesce after a bout of tuberculosis, Rib came back to North America. Arriving in New York, friends suggested that he go to Ottawa, where he turned up in late 1913, that halcyon time before the outbreak of World War I.

Young Rib, circa 1913What he did in Ottawa for a living during the next year is not entirely clear. Using a small legacy left to him by his mother, Rib began importing German wines and champagne, helping to supply Ottawa’s wealthy lumber barons, politicians and lobbyists with their favourite tipple. But his earnings could not have amounted to much. Other reports suggested that he was briefly a civil servant, or that he worked as a clerk, again at Molson’s Bank. But there is no solid evidence to support either contention. Others claimed that he was a German spy. While Rib might have been a bit of a snoop, this allegation is barely credible either. There was very little to spy on in pre-World War I Canada. Moreover, the German government was unlikely to employ a secret agent who was barely out of his teens. One thing certain, however, is that Rib made a huge splash on Ottawa’s small social scene.

Young Rib, circa 1913What he did in Ottawa for a living during the next year is not entirely clear. Using a small legacy left to him by his mother, Rib began importing German wines and champagne, helping to supply Ottawa’s wealthy lumber barons, politicians and lobbyists with their favourite tipple. But his earnings could not have amounted to much. Other reports suggested that he was briefly a civil servant, or that he worked as a clerk, again at Molson’s Bank. But there is no solid evidence to support either contention. Others claimed that he was a German spy. While Rib might have been a bit of a snoop, this allegation is barely credible either. There was very little to spy on in pre-World War I Canada. Moreover, the German government was unlikely to employ a secret agent who was barely out of his teens. One thing certain, however, is that Rib made a huge splash on Ottawa’s small social scene.

Fluent in English and French as well as German, the tall, elegant, blue-eyed Teuton presented a dashing figure, and was an immediate hit among Ottawa society debutantes. A champion schmoozer, he became a fixture at the best parties. Being an expert violinist, Rib also joined an amateur Ottawa orchestra deemed the best in Canada. This too facilitated his access to the cream of society who was starved for good entertainment. His first known appearance at a society event was at a Christmas charity function for needy children put on in December 1913 by the May Court Club. Rib helped Father Christmas hand out presents.

In May 1914, Rib appeared in Ottawa’s premier “Kermiss,” a charity theatrical event held at the Russell Theatre on behalf of the Victorian Order of Nurses. The production drew rave reviews. The Evening Citizen enthused that “not for many years has the capital seen a spectacle so surpassing in brilliance, so bewildering in its riot of color, yet so wholly enjoyable.” Powdered and bewigged, Rib performed a stately “Royal Minuet” with other young men and women of Ottawa’s high society.

The centre of the social whirl in Ottawa during those pre-war years was Rideau Hall, the residence of Canada’s Governor General, the Duke of Connaught. The German-speaking Duke was the third son of Queen Victoria. His wife was Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia. Rib was introduced to the vice-regal couple, by Arthur Fitzpatrick, the son of Canada’s Chief Justice, Sir Charles Fitzpatrick. The suave and debonair German was invited to Rideau Hall for dinner on at least two occasions, where he conversed with the Duchess in her first language.

Rib was also popular with the young men of the city. At his rooms at the Sherbrooke boarding house located at the corner of O’Connor and Slater Streets, Rib installed parallel bars, a flying swing, and a vaulting horse. There, he entertained his friends with gymnastic feats. In the evenings, he dined regularly with other residents of the house, which included a reporter for the Ottawa Free Press, an employee at the Parliamentary Library, an Ashbury College teacher, and a public servant. Never the retiring type, Rib told his friends that “a great future was in store for him.” Rib had few vices. Despite being a wine seller, he was a teetotaller. While he enjoyed a game of poker, he never played for large stakes. On weekends, he went for walks in Rockcliffe, or played tennis at the Rideau Club. Considered one of the Club’s best players, you could count on Rib to turn out nattily attired in court whites, completed with a black bow tie. In the winter of 1913-14, Rib also joined the Minto Skating Club, and accompanied its skating team to a competition that February for the “Ellis Memorial Trophy” in Boston.

This charmed existence came to an end with Rib’s hurried departure for New York on that fateful August day. He left without paying a number of bills. Sometime after Rib had left the country, his doctor received a letter requesting that his medical bill be sent to an address in Switzerland. The $156 bill, a large sum in those days, was paid in full. Rib neglected, however, to pay his druggist, Harry Skinner of Wellington Street, to whom he owed $1.38. And he never repaid the $10 he borrowed from James Sherwood.

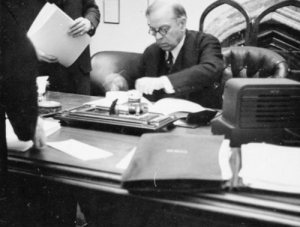

The “Ottawa lad” known as “Rib” to his friends was indeed destined to go far…and to fall even farther. Better known to the world as Joachim von Ribbentrop, he became Germany’s Minister for Foreign Affairs in 1938, the architect of the Russian-German non-aggression pact that immediately preceded the start of World War II. The pleasant young man that had charmed Ottawa high society a quarter century earlier had morphed into an ardent Nazi, fanatically loyal to Adolph Hitler. Following his trial by the Allies in Nuremburg after the war, he was hanged on 16 October, 1946 for war crimes, including his participation in Nazi efforts to exterminate Europe’s Jews.

Sources:

Bloch, Michael, 1992. Ribbentrop, A Biography, Crown Publishers, Inc.

Gwyn, Sandra, 1992. Tapestry of War, Harper Collins, Toronto.

Lawson, Robert, 2007. “Joachim von Ribbentrop in Canada, 1910-1914, A Note,” The International History Review, Vol. 29, No. 4.

von Ribbentrop, Joachim 1954. The Ribbentrop Memoirs, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1954.

Schwartz, Paul, 1943. This Man Ribbentrop: His Life and Times, Julian Messner Inc. New York.

Boston Evening Transcript, “Boston Skaters Winners,” 24 February 1914.

Hamilton Spectator, “Ribbentrop Sold His Wines in Ottawa,” 15 December 1945.

Ottawa Journal, “Ottawa’s Premier Kermiss Was a Feast of Song and Dance for Charity,” 6 May 1914.

—————–, “In Ottawa, Von Rib Foresaw Great Future, 15 June 1945.

——————, “Von Rib’s Days in Ottawa, Nazi Gangster Has C.S. Post, Paid Up Physician in Full,” 16 June 1945.

The Evening Citizen, “The Kermiss,” 6 May 1914.

Toronto Daily Star, “Ribbentrop a Cad Owed Ottawa Bill,” 16 June 1945.

Image: “Rib,” 1913, unknown.

Image: Reichsaussenminister, 1938, unknown.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.