23 July 1912

It ended with a crash that sounded like a great gun going off, the noise reverberating off the buildings of downtown Ottawa. After faithfully serving the Capital for more than eighty years, Sappers’ Bridge finally succumbed to the wreckers in the wee hours of the morning of Tuesday, 23 July 1912. However, the old girl didn’t go gently into that good night. It took seven hours for the structure to finally collapse in pieces into the Rideau Canal below. After trying dynamite with little success, the demolition crew rigged a derrick and for hours repeatedly dropped a 2 ½ ton block onto the platform of the bridge before the arch spanning the Canal gave way. Mr. O’Toole the man in charge of the demolition, said that the bridge was “one of the best pieces of masonry that he [had] ever taken apart.”

View of the Rideau Canal and Sappers’ Bridge – Painting by Thomas Burrowes, c. 1845, Archives of Ontario, Wikipedia.The bridge, the first and for many decades the only bridge across the Rideau Canal, dated back to the dawn of Bytown. In the summer of 1827, Thomas Burrowes, a member of Lieutenant Colonel John By’s staff, gave his boss a sketch of a proposed wooden bridge to span the Rideau Canal, which was then under construction, from the end of Rideau Street in Lower Bytown on the Canal’s eastern side to the opposing high ground on the western side. Colonel By accepted the proposal but opted in favour of building the bridge out of stone rather than wood. Work got underway almost immediately, with the foundation of the eastern pier begun by Mr. Charles Barrett, a civilian stone mason, though the vast majority of the workers were Royal Sappers and Miners. On 23 August 1827, Colonel By laid the bridge’s cornerstone with the name Sappers’ Bridge cut into it. The arch over the Canal was completed in only two months. On the keystone on the northern face of the bridge, Private Thomas Smith carved the Arms of the Board of Ordnance who owned the Canal and surrounding land. The original bridge was only eighteen feet wide and had no sidewalks.

View of the Rideau Canal and Sappers’ Bridge – Painting by Thomas Burrowes, c. 1845, Archives of Ontario, Wikipedia.The bridge, the first and for many decades the only bridge across the Rideau Canal, dated back to the dawn of Bytown. In the summer of 1827, Thomas Burrowes, a member of Lieutenant Colonel John By’s staff, gave his boss a sketch of a proposed wooden bridge to span the Rideau Canal, which was then under construction, from the end of Rideau Street in Lower Bytown on the Canal’s eastern side to the opposing high ground on the western side. Colonel By accepted the proposal but opted in favour of building the bridge out of stone rather than wood. Work got underway almost immediately, with the foundation of the eastern pier begun by Mr. Charles Barrett, a civilian stone mason, though the vast majority of the workers were Royal Sappers and Miners. On 23 August 1827, Colonel By laid the bridge’s cornerstone with the name Sappers’ Bridge cut into it. The arch over the Canal was completed in only two months. On the keystone on the northern face of the bridge, Private Thomas Smith carved the Arms of the Board of Ordnance who owned the Canal and surrounding land. The original bridge was only eighteen feet wide and had no sidewalks.

Reportedly, one of the first civilians to cross Sappers’ Bridge was little Eliza Litle (later Milligan), the six-year old daughter of John Litle, a blacksmith who had set up a tent and workshop where the Château Laurier Hotel stands today. Apparently, Eliza was playing close to the Canal bank on the western side when she was frightened by some passing First Nations’ women. She ran screaming towards Sappers’ Bridge which was then under construction. A big sapper picked Eliza up and carried her over a temporary wooden walkway and dropped her off at her father’s smithy.

Back in those early days, there were two Bytowns. Most people lived in Lower Bytown. It had a population of about 1,500 souls, mostly French and Irish Catholics. The much smaller Upper Bytown, which was centred around Wellington Street roughly where the Supreme Court is situated today, had a population of no more than 500. This was where the community’s elite lived, mainly English and Scottish Protestants. The two distinct worlds, one rowdy and working class, the other stuffy and upper class, were linked by Sappers’ Bridge. While the bridge joined up Rideau Street on its eastern side, there was only a small footpath on its western side. The path wound its way around the base of Barrack Hill (later called Parliament Hill), which was then heavily wooded, past a cemetery on its south side that extended from roughly today’s Elgin Street to Metcalfe Street, until it reached the Wellington and Bank Streets intersection where Upper Bytown started. It wasn’t until 1849 that Sparks Street, which had previously run only from Concession Street (Bronson Avenue) to Bank Street, was linked directly to Sappers’ Bridge. During the 1840s, that stretch of path to Sappers’ Bridge was a lonely and desolate area. It was also dangerous, especially at night. It was the favourite haunt of the lawless who often attacked unwary travellers. Many a score was settled by somebody being turfed over the side of the bridge into the Canal. People travelled across Sappers’ Bridge in groups: there was safety in numbers.

Bytown, which became Ottawa in 1855, quickly outgrew the original narrow Sappers’ Bridge. In 1860, immediately prior the visit of the Prince of Wales who laid the cornerstone of the Centre Block on Parliament Hill, six-foot wide wooden pedestrian sidewalks supported by scaffolding were added to each side of the existing stone bridge. This permitted the entire 18-foot width of the bridge to be used for vehicular traffic.

But only ten years later, the bridge was again having difficulty in coping with traffic across the Rideau Canal. There was discussion on demolishing Sappers’ Bridge and replacing it with something much wider. The Ottawa Citizen opined that such talk verged on the sacrilegious as Sappers’ Bridge was “an old landmark in the history of Bytown.” The newspaper also thought that it was far too expensive to demolish especially as the bridge had “at least another century of wear in it.” It supported an alternative proposal to build a second bridge over the Canal.

In late 1871, work began on the construction of that second bridge across the Canal linking Wellington Street to Rideau Street, immediately to the north of Sappers’ Bridge. It was completed at a cost of $55,000 in 1874. It was called the Dufferin Bridge after Lord Dufferin, Canada’s Governor General at that time. Another $22,000 was spent on widening the old Sappers’ Bridge on which were laid the tracks of the horse-drawn Ottawa Street Passenger Railway.

Despite the upgrade, Ottawa residents were still not happy with the old bridge. Sappers’ Bridge was a quagmire after a rainstorm. On wag stated that “It is estimated that the present condition of the bridge has produced more new adjectives that all the bad whiskey in Lower Town.” One Mr. Whicher of the Marine and Fisheries Department was moved to write a 24-verse parody of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem The Bridge about Sappers’ Bridge. In it, he referred to “many thousands of mud-encumbered men, each bearing his splatter of nuisance.” He hoped that a gallant colonel “with a mine of powder, a pick and a sure fusee (sic)” would blow it up. His poem was well received when he recited it at Gowan’s Hall in Ottawa.

But it took another thirty-five years before the government contemplated doing just that. As part of Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s plan to beautify the city and make Ottawa “the Washington of the North,” the Grand Trunk Railway began in 1909 the construction of Château Laurier Hotel on the edge of Major’s Hill Park, and a new train station across the street. Getting wind of government plans to build a piazza in the triangular area above the canal between the Dufferin Bridge and Sappers’ Bridge in front of the new hotel, Mayor Hopewell suggested that Sappers’ Bridge might be widened as part of these plans in order to permit the planting of a boulevard of flowers and rockeries to hid the railway yards from pedestrians walking over the bridge. He also added that public lavatories might be installed beneath the piazza.

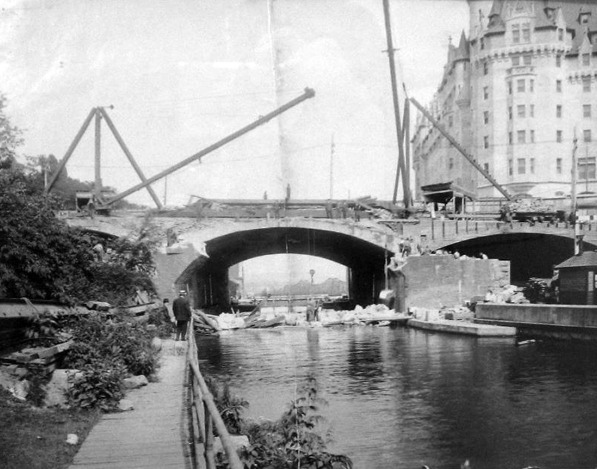

Demolition of Sappers’ Bridge, 1912. The arch of Sapper’s bridge is gone leaving only the broken abutments and rubble in the Canal. The newly built Château Laurier hotel in in the background on the right. Dufferin Bridge is in the centre of the photograph. Bytown Museum, P799, Ottawahh.In the event, the federal government decided to demolish Sappers’ Bridge. Both the Dufferin and Sappers’ Bridges were replaced by one large bridge—Plaza bridge. This new bridge was completed in December 1912. The piazza over the Canal was also built. It was bordered by the Château Laurier Hotel, Union Station, the Russell House Hotel and the General Post Office. A straw poll conducted by the Ottawa Citizen newspaper of its readership, favoured naming the new piazza “The Plaza.” However, the government, the owner of the site, had other ideas. It decided on calling it Connaught Place, after Lord Connaught, the third son (and seventh child) of Queen Victoria who had taken up his vice-regal duties as Canada’s Governor General in 1911.

Demolition of Sappers’ Bridge, 1912. The arch of Sapper’s bridge is gone leaving only the broken abutments and rubble in the Canal. The newly built Château Laurier hotel in in the background on the right. Dufferin Bridge is in the centre of the photograph. Bytown Museum, P799, Ottawahh.In the event, the federal government decided to demolish Sappers’ Bridge. Both the Dufferin and Sappers’ Bridges were replaced by one large bridge—Plaza bridge. This new bridge was completed in December 1912. The piazza over the Canal was also built. It was bordered by the Château Laurier Hotel, Union Station, the Russell House Hotel and the General Post Office. A straw poll conducted by the Ottawa Citizen newspaper of its readership, favoured naming the new piazza “The Plaza.” However, the government, the owner of the site, had other ideas. It decided on calling it Connaught Place, after Lord Connaught, the third son (and seventh child) of Queen Victoria who had taken up his vice-regal duties as Canada’s Governor General in 1911.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the beautification of downtown Ottawa continued. The Federal District Commission, the forerunner of the National Capital Commission, expropriated the Russell Block of buildings and the Old Post Office to provide space for a national monument to honour Canada’s war dead. The war memorial was officially opened in 1939 by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. In the process, Connaught Place was transformed into Confederation Square.

Little now remains of the old Sappers’ Bridge. Hidden underneath the Plaza Bridge is a small pile of stones preserved from the old bridge with a plaque installed by the NCC in 2004 in honour of Canadian military engineers. The bridge’s keystone with the chiselled emblem of the Ordnance Board was also saved from destruction. For a time it was housed in the government archives building but its current location is unknown.

Sources:

Ross, A. H. D. 1927. Ottawa Past and Present, Toronto: The Musson Book Company.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1871. “editorial,” 3 May.

————————, 1972. “A Dirty Bridge,” 10 April.

————————, 1874. “Sappers’ Bridge,” 9 October.

————————, 1913. “‘Connaught Place’, Cabinet’s Choice of Name for Area Formed By Union of Sappers’ and Dufferin Bridges,” 24 March.

————————, 1925. “Muddy Sappers’ Bridge In the Seventies,” 18 July.

———————–, 1928. “Girl of Six Was the First Female To Cross Sappers’ Bridge Over Canal,” 23 June.

The Ottawa Evening Journal, 1910. “Widening of the Bridges,” 3 June.

———————————–, 1912. “Early Days In Bytown Some Reminiscences,” 27 April.

———————————–, 1912. “When Ottawa Was Chosen The Capital of Canada,” 4 May.

———————————–, 1912. “Bridge Is Blown Down,” 23 July.

———————————–, 1914. “Notable Stones In the History Of The Capital,” 16 March.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.