28 September 1826

Bridges are amazing structures. Spanning rivers, gorges, bays and even open ocean, they are testaments to the ingenuity of the engineers who designed them and the courage and ability of the workers who constructed them. Who hasn’t crossed a bridge and wondered what’s holding it up and experienced a frisson of excitement or even terror? The longest bridge in the world over water connects Hong Kong to Macau and the city of Zhuhai on the Chinese mainland, a distance of 55 kilometres, of which a 6.7-kilometre stretch midway is an under-water tunnel between two artificial islands to allow ocean-going ships to travel up the Pearl River estuary. It opened in 2018. Canada’s Confederation Bridge, which links Prince Edward Island to New Brunswick, is 12.9 kilometres long. At the other extreme is Bermuda’s Somerset Bridge that connects Somerset Island with the “mainland.” Dating back to 1620, it is reputedly the smallest drawbridge in the world. Operated by hand, it is just wide enough to allow a mast of a sailboat travelling between the Great Sound and Ely’s Harbour to pass through the gap.

In Canada’s capital, six bridges span the mighty Ottawa River: the Alexandra (or Interprovincial) Bridge; the Champlain Bridge; the Chaudière Bridge; the Macdonald-Cartier Bridge; the Portage Bridge; and the Prince of Wales Bridge (now closed). While the current Chaudière Bridge dates from 1919, it is the site of the first and for a long time the only bridge across the Ottawa River.

The need for a bridge crossing the Ottawa River became apparent after work commenced on the Rideau Canal in the summer of 1826 under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers. With only wilderness on the Upper Canada side, workers and supplies had to be ferried across the river from Wright’s Town (later known as Hull) in Lower Canada, the only settlement of any consequence in the region, where labourers were billeted and shops and stores could be had. (American Philemon Wright had founded Wright’s Town in 1804.) As this was unsatisfactory to all, Colonel By and his engineering colleagues decided to build a bridge as quickly as possible, their haste probably encouraged by the approach of winter.

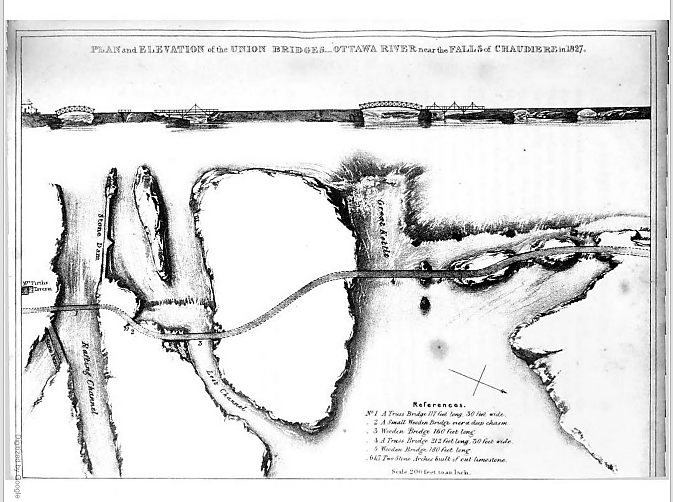

Plan and Elevation of the Union Bridge in Joseph Bouchette, The British Dominions in North America, London, 1832.

Plan and Elevation of the Union Bridge in Joseph Bouchette, The British Dominions in North America, London, 1832.

Their plan was to build a series of bridges to link Lower Canada on the northern shore of the Ottawa River to Upper Canada on the southern shore at the Chaudière Falls where the river temporarily narrows, using the islands mid-river as stepping stones. All were to be made of stone and masonry except for the widest section which was to be made of wood given the width of the gap, the depth of the water and the speed of the current. Col. By later modified this plan. Five of the seven bridges were made of wood—(from south to north over the river,) a 117-foot truss bridge, a small bridge over a deep chasm, a 160-foot bridge, a 212-foot truss bridge, a 180-foot bridge, and two limestone bridges.

After a quick survey—these were the days long before environmental assessments—construction began. On 28 September 1826, General George Ramsay, 9th Earl Dalhousie and Governor General of British North America, placed several George IV silver coins under a foundation stone on the Lower Canadian shore. Colonel Durnford of the Royal Engineers, Colonel John By, and a number of prominent area landowners, including Nicholas Sparks, Thomas McKay and Philemon Wright, attended the ceremony.

Three weeks into the construction, the first masonry arch on the Lower Canada side collapsed when the temporary supporting falsework was removed. Colonel By ordered work to recommence immediately with new plans drawn up by Thomas Burrowes, the assistant overseer of works. The new, hammered stone arch was completed by early January 1827 despite atrocious working conditions. Spray from the nearby falls froze thickly onto the workers’ clothes despite rough wooden screens being installed to shelter them. The second arch was finished by the summer of 1827.

The biggest challenge was bridging the Chaudière itself, also known in English as the Giant Kettle. To link its two sides, Captain Asterbrooks of the Royal Artillery fired a brass cannon loaded with a ½-inch rope to workmen on Chaudière Island. Twice he failed, the rope breaking. But he succeeded with a 1-inch rope. Once workers had a hold of it, they were able to haul over larger cables. Two ten-foot wooden trestles were constructed on either side with ropes stretched over their top and fastened to the rocks. The workers fashioned a precarious footbridge with a rope handrail. It swayed in the wind and sagged to within seven feet of the raging torrent beneath it. It must have been terrifying to cross. In his 1832 book The British Dominions in North America, Joseph Bouchette wrote: “We cannot forebear associating with our recollections of this picturesque bridge the heroism of a distinguished peeress [Countess Dalhousie], who we believe, was the first woman to venture across it.” The bridge’s ropes were then replaced with stronger chains. But as workmen were planking the floor of the bridge, the last step in its construction, disaster struck. First one then the other chain broke, throwing men and their equipment into the raging torrent. While accounts vary, as many as three men drowned.

Undeterred by the tragedy, Colonel By immediately got back to work. This time, workmen constructed stronger trestles and bridged the gap with two 8-inch link chain cables. Two large scows, a type of flat-bottomed boat, were built and moored securely in the location of the bridge. Jack screws placed on the scows supported the bridge during its construction. Unbelievably, just prior to the bridge’s completion, a strong gale flipped it over. Workmen were obliged to cut the bridge free which sent it sailing down the Ottawa river, coming to land close to the entrance of the Rideau Canal. Reportedly, the Chief workman, Mr. Drummond, shed tears in frustration.

Again, Colonel By persevered; his next bridge held. Supported by chains made of 1 3/4-inch thick iron and 10-inch links, the wooden bridge was 212 feet long, 30 feet wide and roughly 40 feet above the water, high enough to escape damage during the spring freshet. It was completed in the summer of 1828, two years after construction had commenced. Upper and Lower Canada were finally united. Fittingly, Col. By called it the Union Bridge.

Lieutenant Pooley, who worked for Col. By, supervised the construction of a final bridge needed to connect Bytown with the new Union Bridge. This bridge spanned a “gully” in what became LeBreton Flats. So impressed was Col. By with Pooley’s round-log bridge that he dubbed it “Pooley’s Bridge.” This name stuck. Lieutenant Pooley’s wooden bridge was replaced by a stone bridge in 1873. It was designated a heritage structure in 1982.

As the Union Bridge was funded by the Imperial Government, Colonel By instituted a toll to help pay for it. The cost was one penny per person, one penny for every horse, ox, cow, sheep and pig, and two pennies for every wagon and sleigh. This was a pretty steep tariff for the times.

Sadly, the Union Bridge did not last. In May 1836, it collapsed into the river and was swept away. Fortunately, there was nobody on it at the time. Again, the only way across the Ottawa River was by ferry.

This all changed in 1843 when the Union Suspension Bridge, constructed by Mr. Wilkinson, an American, opened for traffic. The bridge had a span of 242 feet. Its iron wire suspension cables, which were imported from Britain to Montreal and ferried to Bytown in barges, supported an oaken plank deck. It was the first of its kind in Canada, and was considered an engineering marvel of the age. The Packet opined that the bridge was “a beautiful piece of work” and that it “reflects great credit to the builder, Mr. Wilkinson.” A big celebration was held at Doran’s Hotel on Wellington Street to mark its opening. Engraved invitations were sent out to guests to attend the “Union Suspension Bridge Ball,” complete with a picture of the completed bridge.

Union Suspension Bridge, Watercolour by F. P. Rubidge, Library and Archives Canada, Arch. Ref. R182-2.

Union Suspension Bridge, Watercolour by F. P. Rubidge, Library and Archives Canada, Arch. Ref. R182-2.

Like its predecessor, the Union Suspension Bridge charged tolls. It was a profitable business. In the June to September period of 1851, Duncan Graham, appointed the (tax) Collector for Bytown in the Finance Department by Earl Cathcart, collected £303. 6s. 7d. (equivalent to more than $1,650) in tolls. This was almost enough to cover his annual salary of $1,500 and the monthly stipend £6. 5s. of Mr Mossop, the bridge keeper, who lived in the toll house rent free. Later, the government put the toll business out to tender. At the 1869 tender, the government set a reserve price of $2,000. This compares with annual tolls collected in the 1865-1868 period ranging from $2,500 to $3,350. The winner of the auction was required to maintain the toll house, and keep the bridge clean of rubbish. In winter, they were also responsible for snow clearance, but were required to leave six inches to facilitate sleigh traffic.

Bridge maintenance was not up to everybody’s standards. People complained that the bridge was dangerous especially at night as its railings were low and weak. “Persons run a very great risk on a dark night of driving into the ‘Devil’s Punch-bowl’” said the Ottawa Citizen. As well, the approaches to the bridge on either side of the river were nearly impassable during rainy weather owing to “the enormous quantity of mud and water collected.” In an agreement with the City, the Dominion government abolished tolls on the Union Suspension Bridge in 1885.

The muddy and rutted entrance to the Union Suspension Bridge, looking towards Ottawa, Topley Studio, c. 1867-70, Library and Archives Canada, PA-012705.In 1889, the Dominion government appropriated $35,000 for a new iron truss bridge to replace the deteriorating Union Suspension Bridge. Messrs. Rousseau & Mather were the contractors. Work commenced at the beginning of August and was completed by the beginning of December of that year. Many were concerned that the 30-foot width of the new roadway was too narrow given the growing amount of traffic between Ottawa and Hull. Appeals to the government to widen the bridge or at least put the two 5-foot sidewalks on the outside of the trestles in order to increase the width of the roadway by 10 feet fell on deaf ears.

The muddy and rutted entrance to the Union Suspension Bridge, looking towards Ottawa, Topley Studio, c. 1867-70, Library and Archives Canada, PA-012705.In 1889, the Dominion government appropriated $35,000 for a new iron truss bridge to replace the deteriorating Union Suspension Bridge. Messrs. Rousseau & Mather were the contractors. Work commenced at the beginning of August and was completed by the beginning of December of that year. Many were concerned that the 30-foot width of the new roadway was too narrow given the growing amount of traffic between Ottawa and Hull. Appeals to the government to widen the bridge or at least put the two 5-foot sidewalks on the outside of the trestles in order to increase the width of the roadway by 10 feet fell on deaf ears.

Twelve years later in 1900, the Great Fire, which destroyed much of Hull and LeBreton Flats, severely damaged the bridge. A vital thoroughfare, the government moved quickly to repair it.

In 1919, the Government condemned the Chaudière bridge as being unsafe. According to the Citizen, just walking over the old bridge was enough to give one “thrills” owing to its “see-saw motion when cars pass over it.” Dominion policemen ensured that too many vehicles didn’t try to cross the bridge at the same time. The replacement bridge was built by the Dominion Bridge Company at a cost of $110,000. It was assembled on the Quebec side and was moved into place using scows. This time, government listened to its critics, and placed the sidewalks on the outside of the piers. Before the new Chaudière bridge was put into position, the old bridge was lifted by four 50-ton hydraulic jacks, placed on rollers, and moved 50 feet downriver to a temporary location so that traffic across the river would not be unduly impeded by the construction.

In 2008, the Chaudière bridge was temporarily closed when an inspection revealed that its stone arches, some of which date back to that first 1820’s bridge, were no longer safe. Following repairs, the government reopened the bridge the following year. It continues to serve thousands of commuters every day.

Sources:

Bouchette, Joseph, 1832. The British Dominions in North America, Vol. 1, London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman.

Bytown Gazette, 1846. “No title,” 14 September.

Canada, Province of, 1867. Report of the Minister of Agriculture for 1866, Ottawa: Hunter, Rose & Company.

Mika, Nick & Helma, 1982. Bytown, The early day of Ottawa, Belleville: Mika Publishing Company.

Ottawa Citizen, 1868. “Editorial,” 19 June.

——————, 1869. “Tolls on Union Suspension Bridge,” 26 July.

——————, 1908. “Civil Servants’ Income Tax,” 17 February.

——————, 1919. “Chaudiere Bridge Gives One Thrills,” 18 August.

——————, 1919. “Are Moving The Old Chaudiere Bridge,” 21 August.

——————, 1929. “Ottawa’s First Bridge And Other Narrations,” 12 October.

——————, 1933. “Chaudiere Toll Bridge 1851, Document Tells of Revenue,” 5 August.

——————, 1981. “By-Gone Days,” 28 February.

Ottawa Journal, 1889,” Supplementary Estimates,” 24 April.

——————, 1889. “The Chaudiere Bridge,” 19 September.

Packet (The), 1847. “The Ottawa-Slides-Steamers-Railroads-Necessary Improvements, etc.” 12 June.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.