12 December 1900

During much of the nineteenth century, only one bridge spanned the mighty Ottawa River linking the burgeoning community of Bytown, later known as Ottawa, with its sister town of Hull on the northern shore. Initially, this was the wooden Union Bridge which was completed in 1828 close to the Chaudière Falls. That bridge collapsed a few years later and was superseded by the Union Suspension Bridge in 1843. This bridge became the main thoroughfare linking Ontario and Quebec for the rest of the century. Condemned in 1919, it was replaced by the Chaudière Bridge which is still in operation today.

In 1880, the Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway Company built a railway bridge across the Ottawa River close to Lemieux Island. Initially called the Chaudière Railway Bridge, its name was later changed to the Prince of Wales Bridge in honour of the eldest son of Queen Victoria, the future King Edward VII. (When this name change occurred is uncertain but it was no later than 1887.) However, the Prince of Wales bridge did not carry pedestrian or carriage traffic, and was far removed from the city centre.

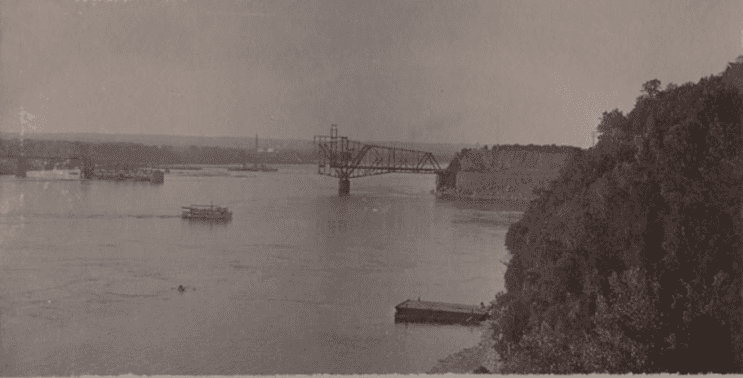

The Inter-provincial Bridge under construction, 1900, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4459589.

The Inter-provincial Bridge under construction, 1900, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4459589.

Discussion of a new interprovincial bridge to the east of the Union Suspension Bridge actually predated the construction of the Prince of Wales Bridge. In 1877, meetings were held at Ottawa’s City Hall on the construction of a railway and carriage road bridge linking Rockcliffe in Ontario with the small Quebec community of Waterloo on the north shore of the Ottawa. The plan was for the Ottawa & Toronto Railway Company to link its rails with the Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway by way of the bridge. There were also plans to build a central depot near Elgin Street linking downtown Ottawa with the Rockcliffe bridge. But the scheme failed to gain political traction with the provincial or federal governments. Bridge supporters had hoped that governments would provide much of the $380,000 needed to fund construction.

In 1883, Sir Charles Tupper, the then Minister of Railways and Canals, put the kibosh on the proposal on the grounds that the road to the bridge had not been completed, and that the Quebec and Ontario governments had not provided any funding. Four years later, a similar proposal was mooted, with a bridge over the Ottawa at Rockland, Ontario. Supporters viewed it as an ideal Jubilee project to celebrate Queen Victoria’s golden anniversary on the throne with the suggestion that it be called the “Victoria Inter-provincial Bridge.” The idea went nowhere.

In 1890, the Pontiac & Pacific Junction Railway (P.P.J.R.) and the related Gatineau Valley Railway Company came up with a new proposal for an interprovincial bridge to link Ottawa to Hull at Nepean Point with a central depot to be built at the Rideau Canal. The price tag was estimated at roughly $800,000 including the cost of building the approaches to the bridge on both shores.

This idea was warmly greeted by important Ottawa citizens and groups, including former mayor Francis McDougal. Ottawa’s City Council, the Ottawa Board of Trade, and the Trades and Labour Council. Other communities in eastern Ontario and western Quebec later came out in support of the proposal. In 1894, the City of Ottawa taxpayers voted in favour of By-law 1,458 to give a “bonus” of $150,000 to the P.P.J.R. upon the completion of a bridge for railway, carriage and pedestrian traffic. Instead of cash, the City would hand over 30-year debentures paying an interest rate of 4 per cent. There were conditions, however. Most importantly, the inter-provincial bridge would have to be completed by July 1897.

Applications for grants also went to the Ontario, Quebec, and Dominion governments. High-powered deputations of railway and municipal officials lobbied members of legislatures. Ontario came through with $50,000 in April 1895, only a fraction of what was sought. The Quebec government chose not to provide any funds. After much delay, the Dominion government provided $212,000. In the meantime, the City of Ottawa twice extended its deadline for the railway to qualify for its $150,000 bonus.

With financing, both private and public, adequately secured, and the plans approved by the Department of Railways and Canals, work finally commenced in February 1898. The bridge would carry a single-track railway line in the centre with two carriage roads and sidewalks for pedestrians.

Including its approaches, the bridge is 2,685 feet long with a clear span of 1,050 feet, the fourth longest bridge of this type in the world at that time. Five piers were constructed to support the structure with the deepest pier located in 70 feet of water. Messrs. McNaughton & Broder were awarded the contract for building the piers. The Dominion Bridge Company of Montreal won the contract for the bridge’s superstructure. The bridge was designed by a team of Canadian engineers led by G.C. Dunn.

Bridge engineers faced some difficult challenges in building the piers owing to sunken logs and sawdust littering the river bed. Before finding bedrock for pier two, workers had to go through eight feet of drowned boards and timbers. At pier three, sawdust thirty feet deep had to be removed using a “clam-shell” dredge. While there were federal laws against fouling waterways, the law apparently did not apply to the Ottawa River—a testament to the political strength of the Ottawa Valley timber barons.

After clearing away the debris at pier two, workers discovered that the bedrock was sharply sloped. To level the area, they blasted the stone using dynamite placed in holes and attached by wires to an electric battery on Nepean Point. Reportedly, the blasts were imperceptible until smoke and bubbles came to the surface of the river. Caissons, built of twelve-inch thick wooden boards, were installed around the work sites. Into them, workers poured cement to form the base of the piers. Ten thousand barrels of cement were used in building the five piers. Stone for the masonry work came from quarries in Rockland and Eganville.

The Ottawa Approach to the Inter-provincial bridge, Nepean Point,

The Ottawa Approach to the Inter-provincial bridge, Nepean Point,

William Topley/Library and Archives Canada, PA-009430.

Another challenge that workers faced was building the approaches to the new bridge, especially on the Ontario side of the River. Labourers carved out thirty-five feet from the face of the cliff at Nepean Point to form the roadbed. A considerable portion of Major’s Hill Park was also sacrificed to make the entrance into downtown Ottawa. As well, the stone abutments of Sappers’ Bridge were pierced to provide an entry for trains into the new central train station located beside the Canal. The stone abutments were replaced by iron and steel supports that allowed for room for the trains.

Given the engineering challenges, the extensive excavation work, and delays in obtaining needed supplies, the construction of the bridge took much longer than expected. There was also the occasional labour action. In January 1900, stone cutters downed tools when their wages were cut from $3 per day prevailing during the previous summer, to $2.50 per day at the beginning of December to only $2 per day.

Because of these delays, work was hurried to ensure that conditions for the Ottawa bonus were met. Despite the haste, however, there seems to have been few accidents, and the ones that did occur were relatively minor.

Whether or not the P.P.J.R. had met all the conditions to qualify for the City of Ottawa bonus of $150,000 in debentures became contentious. Some aldermen as well as the City’s engineer maintained that the railway had failed to meet an intermediate condition of spending a minimum of $50,000 on the construction by the middle of March 1898. Consequently, they wanted to withhold the bonus. The railway said otherwise and threatened to sue. In the event, the bonus was eventually paid. There was also controversy over the nature of the bonus. Since the time the bonus was originally agreed, interest rates had fallen from 4 per cent to 3 ½ per cent. This implied that market value of the debentures had increased significantly. Instead of $150,000, the bonus was effectively worth roughly $162,000. There were unfavourable comments in the press about the City’s financial acumen in promising to give the railway company marketable debentures rather than cash.

The small announcement of the first bridge transit,

The small announcement of the first bridge transit,

12 December 1900. The Ottawa Evening Journal.

Another hiccup along the way was a proposal by a consortium of investors led by the Hull & Alymer Electric Railway to build another bridge across the Ottawa River, with the Ottawa end coming out at roughly Bank Street. The idea was to provide electric streetcar service from Hull to the Ottawa shore of the Ottawa River. The proposal was warmly greeted by both the Hull and Ottawa city councils as well as the Ottawa Retail Merchants Association, especially as the backers of the bridge were not seeking public money. However, there was strong opposition from the Inter-provincial Bridge Company, which was owned by the P.P.J.R., that argued that the new bridge would divert business away from its bridge. As well, the Ottawa Electric Railway owned by Thomas Ahearn, complained that should the Hull streetcar company provide service to Ottawa, even just to the Ontario shore of the Ottawa River, its monopoly rights would be infringed. The proposed Bank Street bridge failed to get a charter from the federal government despite several attempts.

By December 1899, the Dominion Bridge Company was ready to start building the building’s superstructure with six barge loads of steel on site. Work moved rapidly from that point. By October 1900, Ontario and Quebec were connected and work was underway in building the roadbed. Venturesome youth were spotted making the dangerous journey across the iron work from one side of the bridge to the other. On 12 December 1900, the first test train made its way over the new bridge without mishap and without fanfare. Only a small announcement in the Journal newspaper celebrated the event. A month later, Chief William F. Powell of the Ottawa Police Force and his wife were the first to drive their carriage over the bridge. They were initially stopped by a bridge guard, but were subsequently allowed to proceed when the Chief identified himself. In mid-February 1901, the inter-provincial bridge was checked out first by Dominion inspectors and subsequently by the City of Ottawa’s inspector and aldermen. Having received a positive assessment, the bridge opened to the general public for the first time at noon, 5 March 1901.

More test trains ran over the bridge, including one consisting of four heavy locomotives drawing several cars bearing heavy loads of stone and steel. Weighing more than 400 tons, far beyond the weight of a usual train, the idea was to test the endurance of the bridge. Not even the slightest tremor was felt.

Another less felicitous milestone occurred on 14 April 1901 when the bridge experienced its first accident. An approaching train spooked a horse pulling a rig occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Lahaise, the owners of a furniture store on Rideau street. The horse galloped across the bridge towards Hull and crashed into a carriage driven by Mr. and Mrs. James Cudd who were out for a pleasure drive. Mr. and Mrs. Lahaise suffered shock and bruises when they jumped from their rig to safety. Pedestrians were also sent scurrying to safety to get out of the horse’s path. While the Lahaise carriage suffered no damage, the Cudds’ buggy sustained a badly twisted wheel and back axle.

The cross-bridge train service from the Hull Station to Ottawa’s new Central Station was officially opened on 22 April 1901; scheduled service had in fact commenced four days earlier. For the big event, both bridge and train were decorated with flags and bunting. On board, were city dignitaries and railway officials. Mr. John Lauzon was the first official paying passenger. Souvenir badges were presented to all on board that inaugural seven-minute journey. Conductor Hoolihan was in charge, with engineer Mr. W. McFall. As the train rolled onto the bridge, Mr. Noe Valiquette, the proprietor of the Cottage Hotel, broke a bottle of wine on the locomotive. Huge crowds of spectators standing on the Dufferin Bridge, greeted the arrival of the train into Ottawa.

Alexandra Bridge today, by SimonP, Wikipedia.

Alexandra Bridge today, by SimonP, Wikipedia.

In August 1901, Ottawa’s Mayor William Morris suggested that the new inter-provincial bridge be called the Royal Alexandra Bridge in honour of the wife of King Edward VII. The bridge’s railway owners readily agreed with the suggestion. The bridge’s “christening” was planned for the following month when Their Royal Highnesses, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, (the future King George V and Queen Mary), came to Ottawa for the unveiling of a monument to Queen Victoria on Parliament Hill. It was proposed that the Duchess would press a button to illuminate the bridge. However, while the bridge was decked out in electric lights, which spelled out the words “Royal Alexandra Bridge” in twelve-foot letters on its side as part of the illumination of the City done specially for the Royal Visit, contemporary newspaper accounts don’t mention whether the Duchess turned the lights on. However, the royal couple did cross the bridge by carriage to visit Hull which was still recovering from the great fire of 1900.

When the Central Station, called Union Station from 1920, was closed for train traffic in 1966, the train tracks on the Alexandra Bridge were removed and the bridge converted entirely to vehicular and pedestrian traffic. In 1995, the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering designated the bridge as a National Historical Civil Engineering Site.

Today, the venerable Alexandra Bridge, the oldest bridge in service across the Ottawa River, is approaching the end of its life. Owned by the federal government, the decision has been made to replace the bridge with construction on its replacement to be completed by 2032.

Sources:

CSCE, 2022. Alexandra Bridge, Ottawa Ontario — Hull, Quebec.

National Capital Commission, 2021. Alexandra Bridge Replacement, December.

Montreal Gazette, 1995. “From The Queen City,” 11 April.

Ottawa Citizen, 1877. “The Inter-Provincial Bridge Scheme, 13 November.

——————, 1877. “The Inter-Provincial Bridge,” 14 November.

—————–, 1883. “Dominion Parliament,” 18 May.

—————–, 1887. “Queen’s Jubilee – Bridge Over The Ottawa,” 23 March.

—————–, 1895. “The Inter-provincial Bridge,”31 January.

—————–, 1997. “New Bridge For The Ottawa,” 22 November.

—————–, 1898. “Everything Arranged,” 11 January.

—————–, 1898. “Work Starts In A Few Days,” 1 February.

—————–, 1898. “Work On The Big Bridge,” 7 February.

—————–, 1898. “The First Pier Started,” 8 February.

—————–, 1900. “Work On Sapper’s Bridge,” 28 February.

—————–, 1900. “The New Bridge,” 17 November.

—————–, 1901. “Bridge Was Inspected,” 18 February.

——————, 1901. “Begun Three Years Ago,” 5 March.

——————, 1901. “The First Runaway,” 15 April.

——————, 1901. “Stood The Test,” 20 April.

——————, 1901. “Formally Opened,” 23 April.

——————, 1901. “Alexandra Bridge,” 8 August.

——————, 1901. “Alexandra Bridge,” 26 August.

——————, 1901. “The Duchess of Cornwall and York,” 21 September

Ottawa Evening Journal, 1887. “Cold Water,” 5 February 1887.

—————————–, 1893. “By-Law No. —,” 6 December.

—————————–, 1894. “Nepean Point Bridge,” 16 June.

—————————–, 1898. “Bank Street Bridge Defeated,” 14 April.

—————————–, 1898. “A Scene Of Great Activity,” 6 June.

—————————–, 1898. “A Stupendous Undertaking,” 15 October.

—————————–, 1900. “Train Over The New Bridge,” 12 December.

—————————–, 1901. “First To Drive Across,” 15 January.

—————————–, 1901. “To Be Named Alexandra,” 15 August.

Woodard, Rick. 2019. “Alexandra Bridge could be replaced within 10 years,” Global News, 19 March.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.