Time immemorial and 7 October 1763

Canada is widely viewed as a young country, its history stretching back no more than a few hundred years to the arrival of French and British settlers to its shores. But this is a very blinkered view of things. The territory that we now call Canada was not terra nullius when the Europeans arrived, far from it. It was instead populated by a diverse group of Indigenous peoples with their own cultures, traditions and languages from the Pacific Ocean in the west, to the shores of the Arctic Ocean in the north, the Great Lakes in the south, and to the Atlantic Ocean in the east. Pre-contact population estimates vary widely, but modern estimates place the population of the Pacific Northwest alone at as much as 500,000. One, therefore, wonders what the population of the entire territory that was to become Canada might have been. Sadly, European traders and settlers brought diseases, such as smallpox, to which the native population had little or no resistance. Whole communities were virtually wiped out within a short period of time. By 1867, the Canadian Indigenous population had fallen to about 125,000 souls, out of a total Canadian population of about 3.7 million, and was to continue to fall for decades after.

Nobody could live in the Ottawa region until the glaciers of the Wisconsin glacial episode had retreated sufficiently to expose the territory. This occurred roughly 11,000 years ago. Recent archaeological work has found traces of humans dating back as much as 8,000 years. Excavations at several locations along the Ottawa River have uncovered many artifacts fashioned by the Laurentian people of the Archaic period. These included the discovery of spear throwers on Allumette Island in Quebec close to Pembroke, Ontario. These implements enabled hunters to propel spears with greater force than relying on muscle power alone. Also found were tools made of stone and bone, knives crafted from slate and copper, scrapers, harpoons, fish hooks, awls and finely-made needles, the latter requiring a high degree of sophistication to manufacture. On Morrison Island, also close to Pembroke, hundreds of grinding stones were found along with axes, drills, and adzes. These early residents were highly skilled and had a strong artistic sensibility. Many bone articles had been delicately engraved.

The archaeological record also shows a continuous human presence right in the National Capital Region since those early days, reflective of its strategic position at the confluence of three major river systems—the Ottawa which flows into the St. Lawrence and from thence to the Atlantic; the Gatineau which extends northward for almost 400 kilometres; and the Rideau which, via a series of portages, provides access southward to the Great Lakes. These waterways were major transportation and trade routes for indigenous peoples, and continued as such well after the arrival of European settlers at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Indeed, the Rideau Canal built in the late 1820s traced the well-travelled indigenous route from Lake Ontario to the Ottawa River.

Indicative of the importance of the region as a trading centre, archaeological digs in the National Capital Region have uncovered an extraordinary range of material brought many hundreds if not thousands of kilometres. These include quartzite from central Quebec, different types of chert (a type of rock) used for making tools from the Hudson Bay, Illinois, and Ohio, ceramics from south of the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron, and copper from the western edge of Lake Superior. Today’s Leamy Lake Park appears to have been a key stopping point with evidence indicating continuous seasonal occupation of the delta at the mouth of the Gatineau River for over 4,500 years. There, indigenous people from all over stopped to meet, trade, and enjoy the rich bounty of natural resources to be found there.

Ottawa First Nation family, J.G. de Sauveur, Engraving, 1801, Library and Archives Canada, 2937181.Other excavations, pioneered by Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, a prominent Bytown physician, identified in 1843 an “Indian burial ground” on the northern shore of the Ottawa River. He uncovered the remains of twenty individuals in communal and individual graves. Also found at this site were ashes from cremations. Recent investigations during the twenty-first century have confirmed the location of the site as Hull Landing, immediately opposite Parliament Hill, now the location of the Canadian Museum of History.

Ottawa First Nation family, J.G. de Sauveur, Engraving, 1801, Library and Archives Canada, 2937181.Other excavations, pioneered by Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, a prominent Bytown physician, identified in 1843 an “Indian burial ground” on the northern shore of the Ottawa River. He uncovered the remains of twenty individuals in communal and individual graves. Also found at this site were ashes from cremations. Recent investigations during the twenty-first century have confirmed the location of the site as Hull Landing, immediately opposite Parliament Hill, now the location of the Canadian Museum of History.

We also know that the Chaudière Falls was a site of considerable spiritual significance to the Indigenous peoples of the region. In 1613, Samuel de Champlain described in his journal the “usual” ceremony that was celebrated at that site. He wrote that after the people had assembled, and a speech given by one of the chiefs, an offering of tobacco on a wooden plate was thrown into the roiling waters of the cauldron to seek the intercession of the gods to protect them from their enemies.

It was Samuel de Champlain who popularized the name for these indigenous peoples—the “Algoumequins” a.k.a. the Algonquins. But the people knew themselves as the Anishinabek, sometimes translated as true men, or good humans.

Following first contact with Europeans at the beginning of the seventeenth century, many eastern First Nations became embroiled in the seemingly endless conflicts between European powers for political and economic ascendancy in North America. The semi-nomadic Algonquins, who were superb hunters and trappers, became key partners with the French in the European fur trade. They supplied pelts from their own extensive territories in the Ottawa and St. Lawrence Valleys, or acted as middlemen for the Cree to the north. In exchange, the Algonquins received firearms that they used to defend themselves from their traditional rivals, the Iroquois First Nations, who were important allies of Dutch settlers to the south, and subsequently the English.

These European struggles culminated in the long conflict between England and France in the mid-eighteenth century, called the Seven Years’ War, which ultimately led to an English victory and France’s loss of its North American colonies with the exception of the important fishing centres on the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon located in the mouth of the St. Lawrence close to Newfoundland.

When Montreal capitulated in 1760 to English forces, the English agreed to a French condition of surrender that their indigenous allies could remain in their traditional territories and would not be molested. Three years later, in June 1763, France ceded its North American territories to the English under the Treaty of Paris.

On 7 October 1763, King George III issued a Royal Proclamation outlining how his new territories in North America would be administered and how relations with the Indigenous communities would be undertaken. The Proclamation stated: “And whereas it is just and reasonable, and essential to our interest and the Security of the Colonies, that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians, with whom We are connected, and who live under our Protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having ceded to, or purchased by Us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds.”

Another provision of the Proclamation forbade private purchases of land from Indigenous peoples, with this right reserved to the Crown. This provision set the basis for the negotiation of future treaties between the Crown and Canada’s indigenous peoples.

Notwithstanding this 1763 Royal Proclamation, Europeans quickly settled on indigenous territories. Following the American War of Independence, which ended in 1783, the Crown gave grants of land to Loyalist refugees coming north to Canadian territory according to their rank and service. These grants were given without the consent of the First Nations.

Here in the greater Ottawa area, Loyalists received grants of land on the Rideau River, including at such places as today’s Merrickville, Burritt’s Rapids, and Smiths Falls. Grants of land along the Ottawa River from Carillon westward to Fassett on the north shore in Quebec and at Hawkesbury in Ontario were also handed out.

In addition, European settlers began settling on indigenous territory in the National Capital Region in 1800 with the arrival of Philemon Wright in what is now the Hull sector of Gatineau. Initially hoping to farm, settlers almost immediately began to exploit the seemingly inexhaustible supply of pine for sale in the United Kingdom and later the United States. Settlement accelerated with the building of the Rideau Canal and the naming of Ottawa as the capital of Canada in 1857.

The clearance of vast tracks of land for farms, lumbering and urban development irrevocably altered the landscape of the Ottawa Valley. By the 1920s, less than four percent of the original, old growth forest was left. For the Algonquins, who had lived for untold centuries in harmony with nature, their way of life was also irrevocably changed. As no treaty had been made with the Crown, the Algonquin First Nations had been marginalized on their own territory. Canada’s capital continues to sit on unceded Algonquin territory in contravention of the 1763 Royal Proclamation.

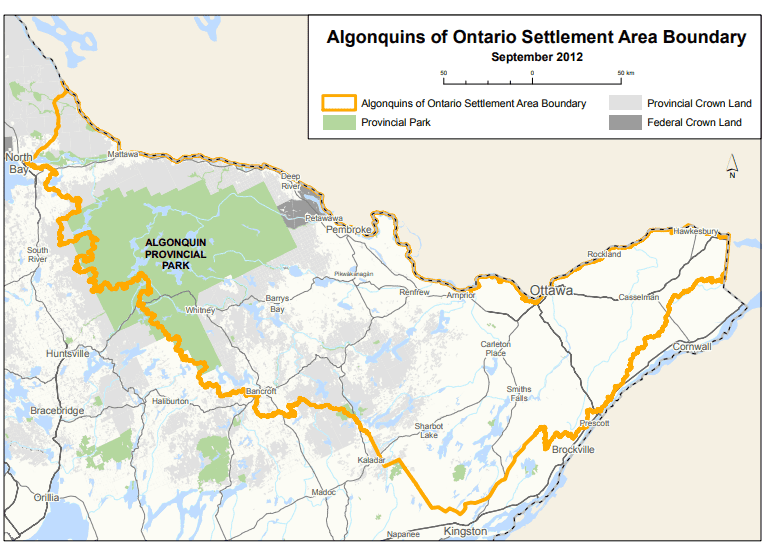

Territorial claims of the Ontario Algonquins, Province of Ontario.

Territorial claims of the Ontario Algonquins, Province of Ontario.

Today, there are ten recognized Algonquin First Nations with a total population of about 11,000. Nine Algonquin communities are in Quebec—Kitigan Zibi, Barriere Lake, Kitcisakik, Lac Simon, Abitibiwinni, Long Point, Timiskaming, Kebaowek, and Wolf Lake. The tenth, Pikwakanagan, is located in Ontario. There are three additional Ontario First Nations that are related by kinship—the Temagami, the Wahgoshig and the Matchewan.

In October 2016, the Algonquins of Ontario reached an agreement-in principle-with the federal government and the government of Ontario to settle all land claims covering some 36,000 square kilometres of land in the watersheds of the Ottawa and Mattawa with a population of 1.2 million. Algonquin territorial claims in Quebec were not covered by the agreement. The agreement-in-principle is viewed as a major milestone towards reconciliation and renewed relations. If ratified, the agreement would lead to the transfer of 117,500 acres of provincial Crown land to Algonquin ownership, the provision of $300 million by the federal and provincial governments, and the definition of Algonquin rights related to lands and natural resources in Ontario. No land will be expropriated from private owners. The agreement would be Ontario’s first, modern-day, constitutionally protected treaty. As of time of writing (2021), a final agreement had not yet been reached.

Sources:

Algonquins of Ontario, 2021. Our Proud History.

Belshaw, John Douglas, 2018. “Natives by Numbers,” Canadian History: Post Confederation, BC Open Textbook Project.

Boswell, Randy & Pilon, Jean-Luc, 2015. The Archaeological Legacy of Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 39: 294-326.

Di Gangi, Peter, 2018. Algonquin Territory, Canada’s History, 30 April.

Hall, Anthony, J. 2019. Royal Proclamation of 1763, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 7 February 2006.

Hele, Carl. 2020. Anishinaabe, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 16 July.

Ontario, Government of, 2021. The Algonquin Land Claim.

Neville, George A. 2018. Loyalist Land Grants Along the Grand (Ottawa) River 1788, Bytown Pamphlet, No. 103, Historical Society of Ottawa.

Pelletier, Gérard, 1997. “The First Inhabitants of the Outaouais; 6,000 years of History,” History of the Outaouais, ed. Chad Gaffield, Laval University.

Pilon, Jean-Luc & Boswell, Randy, 2015. “Below the Falls; An Ancient Cultural Landscape in the Centre of (Canada’s National Capital Region) Gatineau,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 39 (257-293).

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.