12 October 1872

Imagine waking up one morning to discover that all motor vehicles had stopped working—no buses, no cars, no trucks, and no airplanes. People wouldn’t be able to get to work or school unless they lived close by. There would be no deliveries of food and merchandise to stores. Farmers would be left with mounds of rotting produce in the field, while factories would grind to a halt owing to a dearth of spare parts and absent workers. Meanwhile, police, firefighters and other emergency response workers would be unable to respond to urgent calls for help. Government would cease to function (okay, there might be an upside). In short, it would be a nightmare.

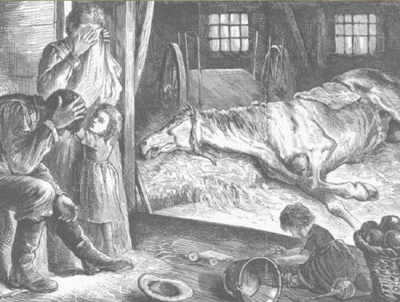

Rather than being a script worthy of a Hollywood post-apocalyptic movie, this effectively happened during the autumn of 1872, with disastrous consequences right across North America. It all started about fifteen miles north of Toronto during late September of that year. Horses in the townships of York, Scarborough and Markham began to sicken, coming down with a sore throat, a slight swelling of the glands, a severe hacking cough, a brownish-yellow discharge from the nose, a loss of appetite and general feebleness. Veterinaries hadn’t seen anything like it before. On 30 September, Andrew Smith, veterinary surgeon of the Ontario Veterinary College in Toronto, found fourteen stricken horses in one stable. Three days later, three-quarters of the horses in the district were infected.

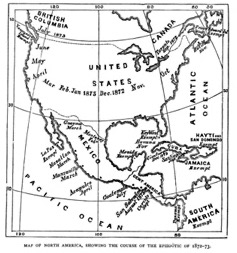

The disease quickly spread to Toronto and beyond. It was reported in Ottawa on 12 October, and within a month had reached the east coast. Only Prince Edward Island, cut off from the mainland, escaped the disease. Horses in the United States also began to sicken, the disease striking Buffalo and Detroit by 13 October, and spreading within days to all the major cities on the eastern seaboard. The illness was identified in Chicago on 29 October after a number of horses imported from Toronto a few days earlier fell ill. By mid-March 1873, the disease had reached all the way to California, in the process disrupting a war between the U.S. cavalry and Apache warriors underway in Arizona Territory. With their horses incapacitated, cavalrymen and warriors fought on foot. A year after the Toronto-area outbreak, the illness had spread south to Nicaragua in Central America. The epidemic became known as the “Great Epizootic,” since it was an epidemic than infected animals, or “Canadian horse distemper.”

The horses were ill with equine influenza which we now know is caused by two types of related viruses, equine 1 (H7N7) and equine 2 (H3N8). But at the time, it was widely believed that the disease was due to something in the air. The Ottawa Daily Citizen reported that it was the opinion of a well-known veterinary surgeon that the disease was caused by atmospheric influences, “probably having some connection with [] recent thunderstorms.” The disease was typically not fatal, having a mortality rate of 1-3 per cent though it reached 10 per cent in some areas. However, the morbidity rate approached 100 per cent. Horses were left incapacitated for up to a month, hobbling transportation across the continent.

Within ten days of its first appearance in Ottawa, the situation had become serious in the capital, with the disease having “assumed a violent form as to cause considerable anxiety to horse owners.” All public livery stables were affected, as were an increasing number of stables owned by private citizens. By 21 October, veterinaries were dealing with hundreds of cases each day. It was estimated that fewer than 50 horses in the Ottawa region were unaffected. The horse-drawn street railway service that provided public transit from New Edinburgh through downtown to LeBreton Flats was temporarily suspended when all but six of its horses came down with influenza. One died.

Within ten days of its first appearance in Ottawa, the situation had become serious in the capital, with the disease having “assumed a violent form as to cause considerable anxiety to horse owners.” All public livery stables were affected, as were an increasing number of stables owned by private citizens. By 21 October, veterinaries were dealing with hundreds of cases each day. It was estimated that fewer than 50 horses in the Ottawa region were unaffected. The horse-drawn street railway service that provided public transit from New Edinburgh through downtown to LeBreton Flats was temporarily suspended when all but six of its horses came down with influenza. One died.

The Ottawa Daily Citizen recommended that infected horses should be kept warm in well-ventilated stables and fed soft food, such as oatmeal, boiled oats, or gruel. To promote an appetite, the newspaper suggested that owners try to temp sick horses with a carrot or apple. It also recommended cleaning out stables with bromo-chloralum, a deodorant and disinfectant. According for an advertisement for the product, it protected against “atmospheric influences which contribute to the spreading of disease.”

Small-town Ottawa got off lightly. Big U.S. cities like New York City and Boston, where horses were crammed together in dirty, multi-storied, urban stables, fared far worse. In New York City, more than 30,000 horses sickened within the course of a few days. At least 1,400 animals died of the disease. City transit failed, a major inconvenience for people living in the suburbs. Businesses and draymen, who transported goods on flat-bed wagons, were reported to be the worst affected. In Boston, oxen were brought in to replace sick horses on some transit lines. Tragically, on 9 November 1872, a fire started in a hoop-skirt factory in downtown Boston. In normal circumstances, it would have been easily contained. However, with all its horses down with the flu, the fire service was unable to respond in time, and the fire quickly got out of control. More than 775 buildings housing in excess of 1,000 businesses were destroyed. As many as twenty people perished.

Epizootic Map of North America showing the spread of epizootic

Epizootic Map of North America showing the spread of epizootic

A. Judson, 1873. "History and Course of the Epizootic Among Horses Upon the North American Continent, 1872-73"The economic consequences of the disease as it spread across the continent were immense. In addition to cities coming to a virtual standstill for close to a month, traffic on the important Erie Canal from New York to Buffalo came to a halt as the horses that pulled the barges sickened. Even railways were affected as they ran out of coal that was shipped to rail terminals by horse-drawn wagons. Things got so bad that the United States was forced to import healthy horses from Mexico. Many economists believe that the Great Epizootic set the stage for the “Panic” of 1873, an economic depression that lasted for six years. The disease underscored the fragility of an animal-dependent economy.

The epidemic was the first disease whose advance was closely tracked across a continent. In the process, it became abundantly clear that “atmospheric conditions” had nothing to do with the contagion. A study of the disease debunked the idea that “cold, heat, humidity, season, climate, or altitude” or any other “unrecognized atmospheric conditions” had any bearing on the disease. Rather, the disease was spread “by virtue of its communicability.” Everywhere the disease struck was in contact with other places by means of horses or mules. Supporting this conclusion was the fact that isolated places, such as Prince Edward Island in the east or Vancouver Island in the west, were spared the disease; PEI was cut off due to bad winter weather, while a quarantine against the importation of horses was established on Vancouver Island. This analysis helped overturn the “miasma” theory of disease, which attributed illnesses to poisonous vapours, in favour of the “germ theory” of disease. It also set the stage for a better understanding of how disease is transmitted among humans, something that would become of vital importance less than fifty years later with the spread of the Spanish flu, a similar human disease that conservatively killed fifty million people at the end of World War I.

Sources:

Churcher, C. 2014, “Local Railway Items from Ottawa newspapers—1872,” The Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1872. “Ottawa City Passenger,” 19 October.

——————–, 2014, “Local Railway Items from Ottawa newspapers—1872,” The Ottawa Free Press, 1872, “Ottawa City Passenger,” 23 October.

Facts on File, 2014. Great Epizootic, Entry 602.

Judson, Adoniram, B. M.D., 1873. “History and Course of the Epizootic Among Horses Upon The North American Continent, 1872-73,” American Public Health Association, Public Health, Reports and Papers, 1873.

Heritage Restorations, H2012. “The Great Epizootic of 1872,” SustainLife Quarterly Journal, (Fall), Ploughshares Institute for Sustainable Culture.

Horsetalk, 2014. “How Equine Flu brought the US to a standstill,” 17 February.

Murnane, Brigadier Dr. Thomas, 2014. James Law, America’s First Veterinary Epidemiologist and The Equine Influenza Epizootic of 1872, The Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation.

Passing Strangeness, 2009. The Great Epizootic, 13 May,.

The Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1872. “Epizootic,” 21 October.

The Public Ledger, 1872. “The Epizootic in the United States,” 16 November.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.