14 February 1915

One of the most curious events in Ottawa’s history occurred on Valentine’s Day night, Sunday 14 February 1915, six months after the start of the Great War. At roughly 10.30pm, the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, received an urgent telephone call from Mayor Donaldson of Brockville informing him that at least three German airplanes had crossed the St Lawrence River from Morristown, New York. The invaders, apparently seen by scores of Brockville citizens who were returning from Sunday evening church services, had just passed directly over the community travelling in a northerly direction, presumably towards the capital. One of the planes shone a powerful searchlight on the town, lighting up its main street. Reportedly, the planes dropped “fireballs,” or “light balls,” into the river on the Canadian side of the border. Many Brockville citizens become hysterical.

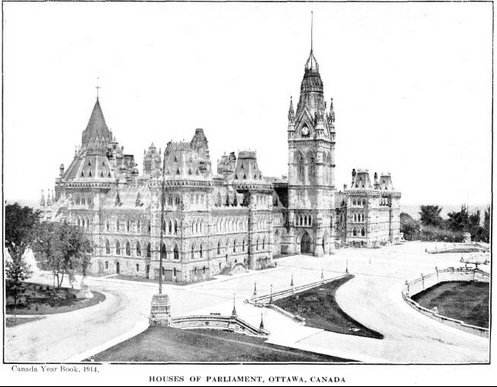

After receiving the mayor’s call, Borden immediately contacted the Canadian Militia. Meanwhile, Brockville’s chief of police telephoned Colonel Percy Sherwood, Commissioner of the Dominion police regarding the air invaders. At 11.15pm, Sherwood ordered Parliament Hill to be blacked out to avoid giving the raiders an easy target. While the phlegmatic Commissioner was not unduly apprehensive about the report of approaching enemy planes, he believed it expedient to take precautionary measures, including blacking-out key government buildings. The lights that illuminated the Centre block’s Victoria Tower when Parliament was in session were extinguished. The Royal Mint, which was also typically lit up at night, was similarly darkened. At Rideau Hall, home of the Governor General, the blinds were drawn. Although the Governor General was away inspecting troops in Winnipeg, his wife, the Duchess of Connaught, was in residence. Other buildings observed the black-out as news of the pending attack hit the streets. The Globe newspaper reported that the entire city of Ottawa was in darkness that night.

Centre Block, Houses of Parliament, Ottawa, 1914.Despite Ottawa being only 100 kilometres distant from Brockville as the crow flies, aviation experts told the Canadian authorities that it might take until midnight for the invaders to make their way to the capital owing to poor weather conditions, which included low clouds and rain. Recall that planes at that time were lucky to go much more than 100 kilometres per hour under favourable conditions. Smith Falls, Perth, and Kempville, which were on the expected flight path, were alerted, and told to keep a sharp look-out. But midnight came and went without any sign of the intruders.

Centre Block, Houses of Parliament, Ottawa, 1914.Despite Ottawa being only 100 kilometres distant from Brockville as the crow flies, aviation experts told the Canadian authorities that it might take until midnight for the invaders to make their way to the capital owing to poor weather conditions, which included low clouds and rain. Recall that planes at that time were lucky to go much more than 100 kilometres per hour under favourable conditions. Smith Falls, Perth, and Kempville, which were on the expected flight path, were alerted, and told to keep a sharp look-out. But midnight came and went without any sign of the intruders.

The next day, newspapers were full of stories on the putative air raid. The Globe’s headline screamed: “Ottawa In Darkness Awaits Aeroplane Raid. Several Aeroplanes Make A Raid Into The Dominion Of Canada.” In the streets of the capital, citizens experienced a frisson of excitement with the war apparently being brought to the city. The Ottawa Journal reported that “Ottawa feels first thrill of war,” and marvelled that usually reserved Ottawa citizens were stopping complete strangers on the street seeking news of the invaders. In the House of Commons, Sir Wilfrid Laurier rose and asked the Prime Minister for any information that he might be able to provide. Borden confirmed that he had received a telephone call from the Mayor of Brockville, and that he had communicated the news of the expected raid to the chief of the general staff, but he was “unable to give the point of departure of the aeroplanes in question.” That night, fearing that the previous night’s attack might have been aborted owing to bad weather and subsequently re-launched, government buildings were blacked out for a second night. Parliament sat as usual, but behind drawn curtains.

For two hours, Ottawa’s city council debated a motion submitted by St George Ward alderman Cunningham “that in view of the possibility of an air raid on the city hall while this august body is in session, Constable McMullen be instructed to pull down the blinds.” The Ottawa Journal wryly noted that the debate occurred under the glare of 61 electric lights which lit up the building. It also noted that the alderman frequently absented himself from the debate to climb the city hall tower to scan the skies for sight of the approaching planes so that he could be the first to warn his colleagues to take shelter in the cellar.

When no planes appeared, people started to look for other explanations. Quickly, suspicion focused on some Morristown youths, described as “village cut-ups,” who admitted to having sent up three “fireworks balloons” from the American side of the St Lawrence at about 9pm which exploded in the air above Brockville. Giving credence to this story, the remains of balloons with firework attachments were subsequently recovered from the ice on the St Lawrence two miles east of the town, as well as from the grounds of the Brockville Asylum, now called the Brockville Mental Health Centre. The ostensible reason for sending up the balloons was to commemorate the centenary of the end of the war of 1812. More likely it was a prank aimed at scaring Canadians.

Officials in Ottawa didn’t readily believe these reports. The Dominion Observatory reported that the wind that night was consistently coming from the east. It contended that as Morristown is directly opposite Brockville, any balloons sent up from the Morristown area would have travelled to the west, and certainly not in the direction the airplanes were said to have taken. The press also reported that militia authorities were in contact with Washington, and that a thorough inquiry had been set in motion to locate the airplanes’ base of operation.

Across the Atlantic in England, which had experienced its first German Zeppelin air raid just three weeks earlier, the phantom air raid on Ottawa was a source of merriment. By chance, the night after the Ottawa scare, the lights of Parliament at Westminster suddenly went out. Making a reference to the Ottawa raiders, William Crooks, Labour MP for Woolwich cheekily called out in the darkness” “Hello, they’re here!” The House of Commons cracked up with laughter.

So what really happened that Valentine’s Day night? How plausible was an attack on Ottawa?

It wouldn’t have been the first time that armed raiders had crossed the U.S. border into Canada. There were precedents. Less than fifty years earlier, the Fenians, an Irish extremist group, made a number of military forays into Canada across the U.S. border. The Ottawa Journal also claimed that German sympathizers in the United States had contemplated action against Canada during the early days of the war in 1914, going so far as to set up training bases in the United States with the objective of “making a descent upon Canada to destroy canals and railways” before being told to desist by U.S. authorities. Less than two weeks prior to the supposed air raid on Ottawa, Werner Horn, a German army reserve lieutenant, tried to blow up the Vanceboro international bridge between St Croix, New Brunswick and Vanceboro, Maine in an attempt to disrupt troop movements.

British B.E.2c, manufactured by the British Air Factor, Vickers, Bristol, circa. 1914.However, an air raid on Ottawa by German sympathizers seems highly unlikely. While on a sharp upward development trajectory, aviation was still primitive in early 1915, the first powered flight having taken place only eleven years earlier. Even at the front in France, airplanes were then mostly used for reconnaissance. Typical of that era, the British military airplane, the B.E.2c, could stay aloft for only three hours.

British B.E.2c, manufactured by the British Air Factor, Vickers, Bristol, circa. 1914.However, an air raid on Ottawa by German sympathizers seems highly unlikely. While on a sharp upward development trajectory, aviation was still primitive in early 1915, the first powered flight having taken place only eleven years earlier. Even at the front in France, airplanes were then mostly used for reconnaissance. Typical of that era, the British military airplane, the B.E.2c, could stay aloft for only three hours.

The most likely explanation is the toy balloon story, combined with a bad case of war jitters. As suggested by one of the newspapers, the searchlight beam that reportedly lit up Brockville could be explained by a fortuitous flash of lightning while the balloons were above the city. However, the fact that the Dominion Observatory was adamant in its view on the wind direction that night fuelled fears that the bombers were real.

Certain modern-day investigators have a whole different explanation—UFOs. The story of Ottawa’s phantom air raid has featured in a number of books on the paranormal, including The Canadian UFO Report: The Best Cases Revealed. To add grist to the paranormal mills, the same night Ottawa prepared for an air raid, strange lights and planes were apparently spotted over other Ontario towns.

Sources:

Colombo, John Robert, 1999. Mysteries of Ontario, Hounslow Press.

House of Commons, 1915. “Reported Appearance of Aeroplanes,” Twelfth Parliament, Fifth Session, Volume One, 15 February.

Rutkowski, Chris & Dittman, Geoff, 2006. The Canadian UFO Report: The Best Cases Revealed, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

The Globe, 1915. “Ottawa In Darkness Awaits Aeroplane Raid,” 15 February.

————————, 1915. “Were Toy balloons and not Aeroplanes!” 15 February.

The Ottawa Journal, 1915. “House To Be Dark Again To-night,” 15 February.

————————, 1915. “Wind From East; Fact That Casts Doubt On Toy Balloon Story; But It Seems Most Likely Explanation,” 15 February.

———————-, 1915. “The Air Raid That Didn’t,” 15 February.

———————–, 1915, “Brockville Statement,” 15 February.

———————–, 1915. “Laughing at Ottawa,” 16 February.

Unikoshi, Ari, 2009. The War in the Air, http://www.firstworldwar.com/airwar/summary.htm.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. 2007. “The Phantom Invasion of 1915,” Rootsweb, Quebec-Research Archives, http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/QUEBEC-RESEARCH/2007-04/1176680122.

Images:

Statistics Canada. Parliament, 1914. http://www65.statcan.gc.ca/acyb07/acyb07_2014-eng.htm.

British B.E.2c, circa 1914, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Aircraft_Factory_B.E.2.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.