29 August 1892

During the late nineteenth century, electricity was the cutting-edge, new technology, and Ottawa was Canada’s high-tech capital, thanks to two factors—the entrepreneurial skills of Thomas Ahearn, and the city’s proximity to the Chaudière Falls. In 1887, Ahearn and his partner, Warren Soper started the Chaudière Electric Light and Power Company. The company began producing relatively inexpensive hydroelectricity at the Falls, thereby helping to power Ottawa’s manufacturing sector and lighting Ottawa’s homes and shops with the new-fangled incandescent lights invented by Thomas Edison. The duo also later operated Ottawa’s electrified urban transit system, the Ottawa Electric Street Railway, whose carriages were electrically heated.

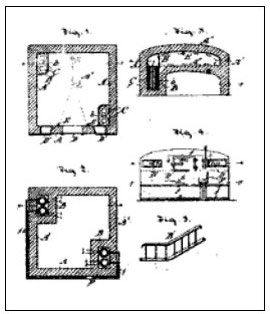

A pictorial description of Thomas Ahearn's electric oven.

A pictorial description of Thomas Ahearn's electric oven.

Canadian Patent Office, 1892In August 1892, the Canadian Patent Office issued three patents to Thomas Ahearn. Sandwiched between his electric water bottle and his electric flat iron, was patent no. 39,916 for an improved electric oven. It was described as “An oven having in its hearth inclosed (sic) pits in which electric heaters are placed.” Just like modern ovens, the interior of Ahearn’s oven was lit by incandescent lamps that allowed a person to monitor whatever was being cooked through a glass window.

While Thomas Ahearn did not invent the first electric oven, there is no doubt that the first dinner entirely cooked using electricity took place in Ottawa on 29 August 1892 at the Windsor House hotel. According to a bemused Ottawa Journal journalist, “a complete repast, comprising a number of courses” was cooked “by the agency of chained lightning.” The hotel proudly proclaimed on its menu that “Every item … has been cooked by the electric heating appliance invented and patented by Mr T. Ahearn of Ahearn & Soper of this city and is the first instance in the history of the world of an entire meal being cooked by electricity.” Even the soup, sauces, and after-dinner coffee and tea were prepared using Ahearn’s electric heaters.

The dinner, or more accurately the feast of some thirty different items, consisted of:

One hundred guests were invited by the hotel’s proprietor, Mr Daniels, to enjoy the banquet. The guest list included Ottawa’s Mayor Olivier Durocher, Warren Soper, as well as the presidents of the Ottawa Electric Railway and the Chaudière Electric Light and Power Companies. Also in attendance were numerous newspaper reporters that ensured widespread publicity. The meal was prepared at the electric tram sheds owned by Ahearn and Soper, and rushed by a special carriage to the hotel located several blocks away. The meal included a twenty-one pound roast of beef, a thirteen pound roast of veal, and three big turkeys that were cooked simultaneously in the cavernous Ahearn oven; apparently, the oven could accommodate twice that amount.

After the meal, which was acclaimed as a huge success, with everything “cooked to perfection,” the guests boarded another special tram and taken to view the oven at the tram sheds. There, Thomas Ahearn, who had stayed back to supervise his oven’s operation, provided an explanatory lecture. The arched brick oven was six feet wide with two Ahearn electric heaters installed in the bottom, powered by electricity generated by the Chaudière Electric Light and Power Company. The “current consumed by the two [heaters] was 43 amperes at 50 volts.” The inside of the oven measured four feet by four feet. Peepholes, covered with heavy plate glass, permitted the chefs to observe the progress of the cooking without having to open the door. A major selling feature was the even cooking of the oven—“no scorching in one part and half-done-ness in another part” said the Evening Journal. As a vote of confidence in the new electric oven, Mr Daniels, the owner of the Windsor House hotel, ordered one of Ahearn’s newly patented ovens to be installed in the hotel’s kitchen.

A few weeks later, there was another, even larger scale, demonstration of Ahearn’s Electric Cooking Oven at the Central Canada Exhibition held in Ottawa. As part of a display of Ahearn electrical products, including electric home heaters, coffee boilers, and special restaurant heaters, a local baker, Mr R.E. Jamieson, used the oven to bake buns, twelve pans at a time, that he sold to the crowds at twenty-five cents each. This was an extraordinary price. A multi-course meal at the Café Parisien on Metcalfe Street could be had for only forty cents. The Electrical Engineer, a New York-based electrical trade journal, quipped that the expression “‘Went off like hot cakes’ now reads in Ottawa ‘went off like electric cakes.’”

The Ahearn oven that the baker used was slightly different from the one used for the Windsor House banquet, having three heating elements instead of two. The extra element was needed to provide additional heat to offset heat loss through the frequent opening of the door in the cooking of multiple rounds of buns. The oven was also equipped with a pyrometer, turn-off switches, interior lights, and a clock. The oven was the hit of the Fair. Thomas Ahearn was awarded a special gold medal for his display of electrical devices.

While Thomas Ahearn and Warren Soper were successful entrepreneurs, making fortunes from their electrically-based, business empire, the Ahearn electric oven proved to be a dud. It was too bulky to be easily used as a household appliance. As well, few homes or businesses were wired for electricity. Even where electricity was available, electric ovens, being energy gluttons, were expensive to operate, and were not initially competitive with the more familiar wood, coal, or gas ovens. It wasn’t until the 1930s that electric ovens became widely accepted.

Sources:

Canadian Patent Office Record and Registrar of Copyrights and Trade Marks, 1893. No, 39,916, Electric Oven, Four Électrique. Vol. 20, Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau.

Daily (The) Citizen, 1892. “Café Parisien,” 8 October.

Electricity, 1893. An Electric Banquet, 14 September, 1892, Volume 3, July 20, 1892 to January 11, 1893.

Electrical (The) Engineer, 1892. Electric Cooking At Ottawa, Can., Volume 14, July-December.

Electrical Review, 1893. A Course Dinner Cooked By Electricity, Volume 21-23, August 27, 1892 to February 18, 1893.

Evening (The) Journal, 1892. “An Electric Banquet,” 30 August.

Innovateus, 2013. Electric Stove.

Library and Archives Canada, 2006. Made in Canada, Patents of Invention and the Story of Canadian Innovation, Thomas Ahearn.

Mayer, Roy. 1997. Inventing Canada: One Hundred Years of Innovation, Vancouver: Raincoast Books.

National Academy of Engineering, 2015. Great Engineering Achievements of the 20th Century.

Images:

Patent No. 39,916, Ahearn Electric Oven, The Canadian Patent Office Record And Registrar of Copyrights and Trade Marks, Vol. 20, Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau, 1893.

Thomas Ahearn’s Oven in Operation, Canada Central Fair, Ottawa, October 1892, The Electrical Engineer, “Electric Cooking at Ottawa, Can.,” Volume 14, July-December, author unknown

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.