24 February 1836

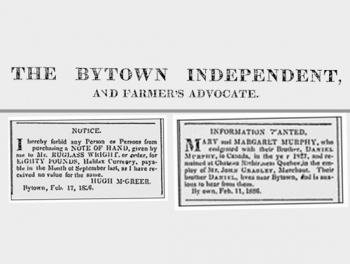

On 24 February 1836, the first edition of the first local newspaper appeared on the streets of Bytown, the small village that was destined to become Ottawa. That newspaper was called The Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate. Its banner on the front page under its name proudly read:

“Let it be impressed upon your minds, Let it be instilled in your children, that the Liberty of the Press is the Palladium of all your civil, political and religious rights.—Sumus.”

The newspaper’s proprietor and editor was James Johnson. An Irish Protestant, Johnson had come to Canada in 1815. In May 1827, he settled in Bytown, which had only been founded the previous year. Reportedly a blacksmith by trade, Johnson quickly became a man of considerable property, earning a living as a merchant and auctioneer in the rough, tough frontier community that was Bytown.

The establishment of a newspaper in the small community was no easy feat, and must have taken many months in put into effect. Johnson purchased his press in Montreal. He personally disassembled it and packed the pieces along with its moveable type in boxes for shipment to Bytown. Most likely, he sent the equipment via boat as there were no railways or good highways linking Bytown to the outside world.

The Prospectus of The Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate was dated December 16, 1835, indicating that Johnson had been working on the newspaper for several months before he released its first issue. He committed to publishing the newspaper every Thursday until demand was such that a semi-weekly publication was warranted. He intended “to advocate the national character and interest of every true Briton—Irishmen and their descendants first on the list.” In addition to being the spokesman for the Irish, Johnson promised to “promote the interests and prosperity of the County of Carleton and the Province [Canada West, i.e. Ontario] in general.” However, he also promised to take “the occasional peep into the affairs of our Sister [Canada East, i.e. Quebec]” since the prosperity of the two Provinces were tightly connected.

Johnson proclaimed that on “all occasions,” the newspaper will “uphold the King, and Constitution by enforcing obedience to the laws.” “May the Union Jack of Great Britain never cease to proudly wave over the Citadel of Quebec,” he declared. However, Johnson was very clear that his allegiance did not extend to the King’s ministers and officers, many of whom he believed incompetent and who put their own self-interest ahead of that of the citizens of the two Provinces. He said that they should be “turned adrift to gain a livelihood by their own industry.” Johnson added that “at all times,” would the newspaper speak out against “any misapplication of public monies, or malefaction with which public officers may be charged.”

One thing the newspaper would not do is to wade into religious controversies, except if “a wonton attack is made upon any body of Christians.” Johnson wrote “every man should be allowed to walk in his own peaceful ways without intolerance, as he is responsible for them to God alone.”

The cost of subscribing to the newspaper, which Johnson promised to publish on “good paper” of “a fair size,” was an expensive £1 or $4 per year, exclusive of postage payable semi-annually in advance. Rates for advertising in the newspaper were set at 2 shillings and sixpence for six lines for the first insertion, with every subsequent insertion set at 7 1/2d. Rates went up for larger advertisements. From six to ten lines, the initial rate was 3s. 6d. with subsequent insertions costing 10d. For submissions of great than ten lines, the rate would be 4d. per line for the first time, and 1d. per line for subsequent insertions.

That first edition had a run of about 500 copies, four pages long, which he produced with the help of John Stewart, his compositor. Johnson tried to deliver by hand all the copies of that inaugural issue of the Bytown Independent as he didn’t want to use the Post Office. Johnson, an irascible and opinionated man, was angry at Bytown’s Deputy Post Master and didn’t want to give him the business. “We have always been ill treated by the Deputy Post Master,” he raged. “To have him enlarge his bags for five hundred copies of the Bytown Independent would be unreasonable on our part.”

Johnson requested that friends and foes alike peruse the newspaper and if they didn’t agree with the paper’s politics they could return the issue by the post. Those who retained the issue would be placed on the Subscribers’ List—an early example of what today is called unsolicited supply. Johnson also advised recipients not to keep a copy out of compassion since if necessary he would seek reforms even if they affected “our best friend.”

Johnson pledged that at the end of the year if he was satisfied with himself, he would treat himself and any well-wishers to a bottle of something that would remain nameless.

Politically, Johnson pledged himself to being neither Whig (Reform) or Tory (Conservative). However, it is evident from the newspaper’s coverage of political events that Johnson was an ardent reformer. The newspaper’s account in its first issue of the evolving Canadian political scene provides a fascinating contemporary look into the turbulent period immediately prior to the Rebellions of 1837 when radical reformers took up arms against repressive, non-representative governments in Upper and Lower Canada.

The first issue of the Bytown Independent took place against the backdrop of a change in the leadership of Upper Canada. Sir John Colborne had just been replaced by Sir Francis Bond Head as Lieutenant Governor. Colborne, a military man who had served under the Duke of Wellington during the Napoleonic War, was conservative by nature and served Upper Canada with an unostentatious style. He successively increased the population of Upper Canada through emigration from Britain and instituted a major public works programme to improve communications across the Province. However, while conscious of the need for constitutional reform, Colborne did nothing to address the provincial political grievances. While many moderates approved of his administration, radical reformers resented his treatment of the House of Assembly, the cost of assisting immigrants, and his use of public funds without the support of the legislature.

Johnson comments on Colborne were scathing and were often close to being libelous. He wrote:

“We can speak of Sir John’s administration from our own knowledge—not from rumours afloat; and we do say this of it, that it was the most puny, partial and political Government that ever any Colony was governed by.”

As well, Johnson, who called Colborne “a scanty head,” accused the Lieutenant Governor of interference in the 1832 by-election in Carleton County. He blamed the election of Hamnet Pinney (or Pinhey), a Tory, over George Lyon, a reformer, by Colborne’s appointment of a corrupt and biased returning officer.

In the newspaper’s first issue, Johnson published the first half of a letter of instructions to Sir Francis Bond Head from Lord Glenelg, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in London. (The second half was to appear in the second issue of the Independent.) The instructions refer to the mammoth Seventh Report of the Select Committee, which had been chaired by William Lyon Mackenzie, on the grievances of Upper Canada’s House of Assembly. The chief grievance was the “almost unlimited extent of the patronage of the Crown,” exercised by the Colonial minister and his advisers. Lord Glenelg made it very clear that he did not favour the appointment of public officials by the legislature, or by any form of popular election. He feared that such public officials would not work for the general good and “would be virtually exempt from responsibility.” Far better for the Lieutenant Governor to appoint able men who would not promote “any narrow, exclusive or party design.” Given the explosive contents of Glenelg’s letter, it was astonishing that Head released it to the press.

A lengthy response to Glenelg’s instructions written by William Lyon Mackenzie, which originally appeared in a Toronto newspaper, was also published. Mackenzie wrote that throughout the two Canadas there was a “general feeling of disappointment and regret.” He added:

“If Sir Francis appoints to Executive Council men…known for their ability, integrity, firmness and sincere attachment to reform principles, his path will be smooth and easy…but if His Excellency shall retain in office the avowed enemies of free institutions, men whom the basest governments of England ever knew, have made use of their minions to oppress our country, it will be our duty at once to demand his recall and insist that a government which is in itself the greatest of all grievances be made suitable to our wants.”

Unfortunately, Head went on to alienate reformers—his arrogance and ignorance a disastrous combination. Although Tories won the General Election in June 1836 owing to Head’s appeals of loyalty to the Crown, his actions against reformers led to rebellion. In late 1837, Mackenzie declared himself president of the short-lived Republic of Canada. But the insurrection quickly fizzled. Mackenzie fled to the United States while Head was recalled in disgrace. These events set the stage for the introduction of responsible government under the leadership of moderates such as Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine during the following decade.

In addition to giving a contemporary account of the political struggle between reformers seeking what Americans might call a “government by the people for the people,” and Tories desiring to preserve an autocracy run by the Governor, the Bytown Independent also provides a fascinating window into economic life of early 19th century Canada. During these years, it was unclear whether British North America would use pounds, shillings and pence or dollars and cents as its currency. British and America coins circulated side by side. Canadian banks, which had just began to circulate their own bank notes, issued paper money in both pounds and dollars, sometimes simultaneously in the form of dual denominated notes. This currency ambivalence can be seen by Johnson setting the price of an annual subscription to his newspaper at $4 dollars in one place and at 20 shillings (£1) in another. It wasn’t until 1857 that the Province of Canada (the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada united in 1841) finally chose dollars and cents—economic ties with its U.S. neighbour trumped political and emotional ties with Britain.

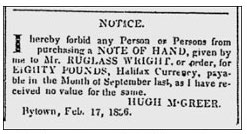

During the early 19th century, promissory notes (notes of hand) were often used as currency. Endorsed on the back, the notes would pass from person to person as money. Ruglass Wright, is probably Ruggles Wright, a son of Philemon Wright who founded Hull. Ruggles, a lumberman like his father, built the first timber slide to transport logs around the Chaudière Falls. In this case, Hugh McGreer is warning potential buyers of the note that he will not pay it if presented.

There is also a reference in the newspaper to “bons”–a form of alternative paper scrip, usually of small denomination issued by merchants which could be used to buy goods in the issuer’s store. Bon stood for “Bon pour,” French for “Good for.”

As well, there is a fascinating reference to “Halifax Currency.” Halifax Currency denoted a way of converting pounds into silver dollars. (It was called Halifax currency after the city where it originated.) One pound, Halifax currency, converted into four silver dollars, or 5 shillings equalled $1. The issuer of a promissory note specified Halifax currency because of the existence of other conversion ratings. For example, in York Currency, which was still in use in parts of Upper Canada in 1836, one silver dollar was worth 8 shillings. To avoid confusion and being short-changed on repayment, it was a sensible precaution to specify the type of currency being used in financial contracts.

Among the advertisements in the newspaper’s first issue are notices from the Post Office listing the times when letters destined for various communities in Upper and Lower Canada had to be received by the Post Office and when letters were delivered at Bytown from these communities. A long list of names of people with mail waiting for them at the Post Office was also provided along with the amount of postage due by them. As these were the days before postage stamps, the recipient of a letter paid the delivery fee. G.W. Baker, the Post Master, warned that unless the amounts were paid by April 5th, the letters would be sent to the dead letter box in Quebec.

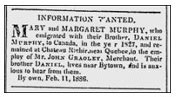

Bytown Independent Personal Ad - 24 February, 1836

The first personal advertisement. One must wonder whether Daniel Murphy ever reconnected with his sister.

In another advertisement, Mr. William Northgraves, a watch and clock maker with an office “nearly opposite the Butcher’s Shambles in Lower Bytown,” announced to Bytown residents that from long experience he had acquired “a perfect knowledge of the practical as well as the theoretical part of the science” and was ready to clean and repair all kinds of watches and clocks. Among other things, he could also repair mathematical and surgical instruments, and make all kinds of fine screws. As a side line, he bought old gold and silver.

Two advertisements were placed in the newspaper by Alexander J. Christie. The first he inserted in his capacity as Secretary of the Ottawa Lumber Association announcing a meeting to be held on March 1st at 10 am at J. Chitty’s Hotel to promote the prosperity of the lumber trade. The second was a request for tenders to clear one hundred acres of land close to Bytown.

Christie must have taken a keen liking in the newspaper. He purchased the The Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate from James Johnson after its second issue. The sale must have surprised the small Bytown community. Christie was a Tory who had helped Hamnet Pinhey win the disputed 1832 Carleton County by-election. Dr. Christie, as he was generally known, was a medical practitioner of uncertain qualifications who had been appointed coroner in 1830 for the Bathurst District in which Bytown was situated. He was also appointed a public notary by Sir John Colborne. Consequently, he represented everything that Johnson had railed against in his newspaper.

Christie relaunched the newspaper a few months later as the Bytown Gazette, and Ottawa and Rideau Advertiser. In his prospectus, Christie claimed that “he comes forward unfettered by a blind adherence to any party.” However, the Gazette’s coverage of political events had a strong Tory bias. After Dr. Christie’s death in 1843, his family held onto the newspaper for a short time and then sold it. During the 1850s, the Gazette was owned by William F. Powell. Subsequently, a Mr. J. McLaurin became the paper’s proprietor. In 1861, McLaurin was charged with practising medicine without a licence. The newspaper appears to have folded about this time.

Bytown regained a local reformist newspaper with the establishment of The Packet in 1843 by William Harris. The Packet was to be renamed The Ottawa Citizen in 1851 and remains the most prominent newspaper in the city to this day.

Sources:

Ballstadt, Carl, 2003. “Christie, Alexander James,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 7. University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed 27 July 2018.

Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate (The), 24 February 1836.

House of Assembly of Upper Canada, 1835, The Seventh Report from the Select Committee on Grievances, chaired by W. L. Mackenzie, Esq., M. Reynolds: Toronto.

Ottawa Citizen, 1851. “The Bytown Gazette And The Solicitor of the Late Corporation,” 26 April.

—————–, 1851. “The Bytown Gazette,” 3 May.

—————-, 1861. “Police Intelligence,” 12 March.

—————-, 1861. “The Liberty of the Press Interfered,” 16 April.

Powell, James, 2005, History of the Canadian Dollar, Bank of Canada.

Wilson, Alan, 2003. “Colborne, John, Baron Seaton,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed 27 July 2018.

Wise, S. W., 1972. “Head, Sir Francis Bond,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed 27 July 2018.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.