22 February 1912

By the beginning of the second decade of the twentieth century, the automobile was no longer the delicate, temperamental curiosity that it was just a decade earlier. In ten years, the internal combustion engine used in most automobiles had been largely perfected. The one-cylinder vehicle, common at the turn of the century, which was noisy, slow and rough to drive, had evolved into a multi-cylinder machine that was, according to the Ottawa Evening Journal, not only a “thing of beauty” but “whisks by you on the street to the tune of a quiet purr, suggesting the passing of a contented cat.” Luxuriously appointed, such cars could go 50 miles per hour compared to less than 20 miles per hour achieved by vehicles a decade earlier, assuming of course drivers could find roads that were not potholed and heavily trafficked by pedestrians and horses.

For the majority of people, however, owing an automobile was a dream rather than a reality. Prices were high relative to incomes, especially during the years prior to the introduction of the assembly line that lowered production costs. In 1912, there were only 500 automobiles cruising the streets of the capital, up from a dozen ten years earlier. Demand was growing rapidly, spurred by the motor car’s many advantages over a horse-drawn vehicle. While the initial outlay for a car or truck was substantial, motor vehicles were more convenient, faster, and could carry heavier loads over longer distances, though winter motoring was problematic. Macdonald & Co., the concessionaire for Albion vans, advertised that the van “could do the work of six horses.” But the automobile’s appeal went far beyond the practical or the economic. In 1912, the Journal summed up the automobile’s almost irresistible appeal. “To own a motor car and enjoy the numerous pleasures that such affords is to own a kingdom. The driver’s seat is a throne, the steering wheel a sceptre, miles are your minions and distance your slave.”

Hundreds of small automobile companies sprang up across North America and Europe to meet the burgeoning demand for cars and trucks. Even Ottawa sported its own automobile manufacturer—the Diamond Arrow Motor Car Company. At its peak, the firm employed as many as twenty mechanics at its plant located at the corner of Lyon and Wellington Streets, just a short walk from Parliament Hill, with a showroom at 26 Sparks Street. Sadly, the firm only produced cars from 1910 to 1912, and disappeared without a trace like so many of the small, craft-style producers, a victim of strong competition, high costs, and the inability to take advantage of economies of scale.

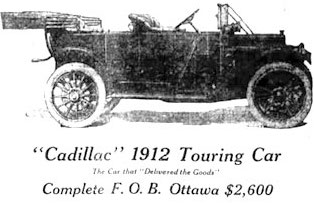

In mid-February 1912, Ottawa held its first automobile show, hosted by the Ottawa Valley Motor Car Association founded five years earlier. The show, which attracted thousands, was held in Howlick Pavilion at the Exhibition Grounds. (The Howlick Pavilion, also known as Howlick Hall or the Coliseum was knocked down in 2012 to make way for the redevelopment of Lansdowne Park.) Some 37 different automobile marques from Canada, the United States, and Europe were on display, ranging in price from an economical $495 to a princely $10,000. Some brands, such as Rolls-Royce, Ford, Oldsmobile and Cadillac, remain household names today. But most, like Jackson, Russell, Tudhope, and Hupp, are long forgotten except by auto historians and antique-car enthusiasts. Show goers were wowed by the latest advance in automobile technology, the self-starter. No longer did a car owner have to get out and manually crank the vehicle to get it started. The 1912 Cadillac also boasted electric headlights—a first in the motoring world. Up until then, car headlamps were filled with oil and acetylene, and had to be manually lit.

With a crowded field, dealers sought ways of standing out among their competitors. Messrs Wylie Ltd of Albert Street advertised that by buying a Tudhope, a Canadian-built vehicle, purchasers avoided the 35 per cent duty levied on the imported cars. Their advertisement argued that the $1,625 Tudhope should be compared “point to point” to imported cars selling for $2,300. The American-made Cutting, selling for $1,725, boasted of its “big, husky power plant;” the Cutting had participated in the first Indianapolis 500 in 1911.

Old Ottawa City Hall, Elgin Street, site of the first leg of the Maxwell Challenge

Old Ottawa City Hall, Elgin Street, site of the first leg of the Maxwell Challenge

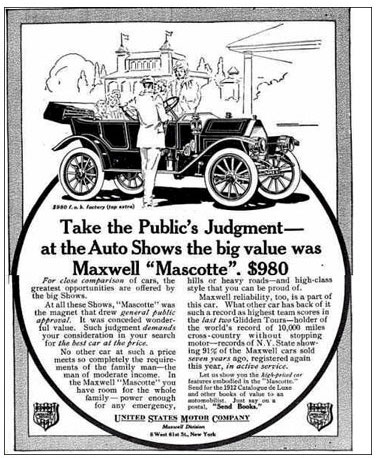

William James Topley, Library & Archives Canada, Mikan No. 3325359Mr F.D. Stockwell, the eastern Canadian distributor of Maxwell motor cars, manufactured by the United States Motor Company, believed action spoke louder than words. To prove the superiority of his automobile, he loaded his Maxwell touring car with twenty boys and drove it up the steps of Ottawa’s City Hall—a considerable feat given the number of steps and the sharp incline. He then drove the car through the deep snow surrounding the building, and pulled a standard car, allegedly twice the weight of his Maxwell, out of a hole. Leaving City Hall, he repeated his stunt on Parliament Hill, driving up the main walkway and up the steps leading to the front of the Centre Block. He again demonstrated the Maxwell’s ability to plough through deep snowdrifts—an important selling feature for cars at the time since few streets and highways were cleared of snow.

After a copycat repeated the stair trick within a half hour of Stockwell’s stunt, and another competitor called the Stockwell’s actions “cheap advertising,” Stockwell retorted that both had ignored “the snow tests.” He then issued the following challenge.

If there is a man in Ottawa selling a touring car from $1,000 to $10,000 (any standard stock touring car, 5 to 7 passengers, not a stripped chassis or runabout), who will drive his machine up the terrace at the City Hall through the snow bank (not doing the path cut through by the Maxwell) we will immediately deposit $100 against one or more cars depositing a like amount for a contest to take place immediately at the Parliament grounds, or anywhere there is a field of good, deep snow.

The proceeds of the bet would got to the charity of the winner’s choice.

Stockwell invited all of Ottawa to come and see who would “meet the Maxwell at the snow plow game.” While he conceded that there were other good cars, he noted that the Maxwell was the only car that for two consecutive years had completed the Glidden tour with a perfect score. The Glidden tour was an American long-distance, automobile, endurance event that began in 1905. The 1911 tour, held in October of that year, was 1,476 miles long from New York to Jacksonville, Florida. It was the most gruelling event up to that time, with the course running along treacherous roads and across streams. Recall this was long before the United States had constructed its inter-state highway system.

Maxwell Car Advertisement, 1912 (US market)

Maxwell Car Advertisement, 1912 (US market)

History of Early American Automobile Industry, 1891-1929The gauntlet was thrown down at 12.30pm on Thursday, 22 February in front of the Ottawa City Hall. Only the Peerless Garage Company, located at 344-348 Queen Street, the distributor of Cadillac, arrived to pick it up. The judges of the challenge were: Mr R. King Farrow, Mr E. H. Code and Alderman Dr Chevrier. What transpired was not exactly what Stockwell, the Maxwell distributor, had in mind.

At City Hall, the Cadillac went first, easily going up and over the building’s terrace without stopping. Stockwell, the driver of the Maxwell, refused to do likewise, but instead shouted out to the other participant “Come up where we will find some real snow at the Parliament Buildings.” The challenge was immediately accepted. On Parliament Hill, the Maxwell went first, having the choice of where to drive. Unfortunately, the automobile had gone only a few yards before it got stuck in a snowbank. Then, it was the Cadillac’s turn. Starting approximately fifteen feet from where the Maxwell had began, the Caddy drove five to seven times further across the snow-covered lawn in from the Centre Block, thereby winning the $100 wager. The Peerless Garage Company donated its winnings in equal amounts of $25 to four Ottawa charities—the “Protestant Home for the Aged” on Bank Street, the “Protestant Orphans’ Home” on Elgin Street, the “St Patrick’s Orphans’ Home” on Laurier Avenue West, and the “Perely Home for Incurables” located on Wellington Street.

Maxwell’s Stockwell immediately issued a second “Maxwell Challenge.” In a letter to the Evening Journal, he admitted that the Cadillac was a good car, and that “it proved a good snow plow, and was cleverly driven.” After adding that the Cadillac cost $600 more than the Maxwell, and that its wheels were two inches higher, Stockwell attributed the Maxwell’s loss to the “misfortune” of having run into a snowbank deposited by a plough before the car got to the open field. After being pulled off the snowbank, he said that the Maxwell had been able to pass the Cadillac that had foundered in deep snow, “its wheels suspended and running freely in the air.” Consequently, Stockwell claimed that the Maxwell was still the champion. He then sent a letter to the Peerless Garage asking for a rematch “on a course which will permit both cars to enter freely the open field, then let the best car win.” He then handed a $100 wager to the sporting editor of the Citizen newspaper, asking him as well as representatives of the Evening Journal and the Ottawa Free Press to act as judges. When the Cadillac representative refused the challenge, Stockwell upped the wager to $150 from him, against $125 from Cadillac, and set the date of the second challenge to the following Saturday afternoon, 25 February, to take place on the snow-covered lawns of Parliament Hill.

Advertisement, 1912 Cadillac, a winner of the first Maxwell challenge, 22 February 1912

Advertisement, 1912 Cadillac, a winner of the first Maxwell challenge, 22 February 1912

The Evening JournalThere was no sign of Cadillac that Saturday afternoon. With the field to himself, Stockwell demonstrated the proficiency of the Maxwell motor car in front of a large crowd of spectators. The Journal reported that the automobile entered the field near the foot of the main steps and slowly circled the field, ploughing gracefully through every ice and snow obstacle. “The Maxwell cut through the biggest drifts on Parliament Hill with consummate ease and was only forced to stop through a broken chain grip.” Stockwell then drove the car down the main walkway “amidst enthusiastic applause” from an appreciative audience.

So, who won the Maxwell Challenge? Clearly, the Cadillac won the first challenge. But, Maxwell achieved at least a moral victory through its subsequent, uncontested challenge match. However, in the highly competitive world of the automobile, Cadillac was the ultimate victor, becoming a North American synonym for luxury and success. The Maxwell, on the other hand, disappeared shortly after the First World War, a victim of the post war depression and large debts. The Maxwell Motor Car Company was purchased by Chrysler in 1921. The last Maxwell was produced in 1925 and was replaced by the Chrysler Four.

Sources:

71st Revival AAA Glidden Tour, 2016. History, 1904-1913.

Bowman, Richard, 2016. Maxwell: First Builders of Chrysler Cars.

Evening Journal (The), 1910. “First Made In This City,” 29 August.

—————————, 1912. “Ottawa, A Popular Motor Car Centre,” 10 February.

—————————-, 1912. Cutting Cars, 1912. “Gather ’round—Come Close—Listen!,” 10 February.

—————————-, 1912. “Motor Car Driving A Recreation In Ottawa,” 10 February.

—————————-, 1912. “A Maxwell Challenge, $100,” 21 February.

—————————-, 1912. “Stockwell Motor Company of Montreal Issued Challenge,” 23 February.

—————————-, 1912. “Cadillac Easily Defeats Maxwell,” 23 February.

—————————–, 1912. “Re that Automobile Competition, Maxwell Challenge No. 2, 23 February.

—————————–, 1912. “The Maxwell Challenge Was Not Accepted,” 26 February.

Macdonald & Company, 1912. “The Albion,” The Evening Journal, 10 February.

Messrs Wylie Ltd, 1912. “What does 35% duty add to the value of a Car?” The Evening Journal, 10 February.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.