Our final in-person speaker presentation of 2023 took place on the afternoon of November 12 and was again hosted by the Main Branch of the Ottawa Public Library. We were pleased to welcome Marc Aubin, author, community historian, former President of the Lowertown Community Association and member of the King Edward Avenue Task Force, who spoke to the 60 attendees about the devastating effects on the Lowertown community of urban renewal projects that took place between the 1950s and 1970s. He began by giving us a brief history and description of Lowertown.

Lowertown, which Marc explained had first been laid out by Colonel By in the 1820s, is bordered by the Ottawa River to the north, the Rideau River to the east, Rideau Street to the south and the Rideau Canal to the west. It was a working class community, primarily French Catholic, but with a significant Irish Catholic component, along with a Jewish community and the first Italian community in Ottawa. Sussex, Dalhousie and St. Patrick were the major local commercial streets, with the Byward Market and Rideau Street being frequented by all citizens of the city. It was a vibrant community, self-reliant and historically one that defended French language rights.

Following the Second World War, a planning policy known as “Urban Renewal” dominated the thinking around housing policy in the governments of western nations. The war had led to a decline in the condition of the housing stock, due to the diversion of the required materials to the war effort. The end of the war created an increased demand for housing from returning veterans starting families. Urban Renewal promoted the wholesale replacement of buildings in what it deemed as “blighted” areas with new social housing projects. It was believed that the clearing of these blighted areas would also yield social benefits by resolving issues including: immorality, vice, crime, juvenile delinquency, infant mortality, poor health and an apathetic population. The introduction of upgraded roadways was also a strong motivation. Not surprisingly, lower income neighborhoods were those chiefly targeted for these renewal projects. The City of Ottawa initially identified a number of communities, the National Capital Commission also being involved, and the affected communities had little to no options for appeal. One of these communities was Lowertown East.

Lowertown East is that section of Lowertown east of King Edward Avenue, covering about 186 acres and consisting of 3 sub-communities, Bishop’s Lots, (early smaller lots), Anglesea Square, (architecturally more similar to Lowertown West) and Macdonald Gardens, (a later community from the 1920s). In 1968 the population of the area was 9,400, 90% of which was French Catholic. There was also a strong Jewish presence and a study taken at that time found that 75% of the residents wanted to stay in the community.

The first large scale urban renewal project in Canada took place in Toronto starting in 1948. In 1956 Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation modified its policies to approve urban renewal projects, for which the City of Ottawa received funding in 1958. In 1962, the National Capital Commission expropriated the northern portion of Lowertown, destroying some 400 housing units. This was followed by the expansion of King Edward Avenue, cutting down 100 large elms, to support the new Macdonald-Cartier Bridge that opened in 1965. The City of Ottawa began expropriation in Lowertown East in 1967, continuing until 1977. In 1971 the first social housing project was opened in Lowertown East. The community had already begun to organize against these renewal projects, as early as 1965, as did other communities within Ottawa. In 1975 key members of the Housing Department resigned over a dispute relating to demolition policy with them Councillor Georges Bedard and Mayor Lorry Greenberg, bringing an end to Urban Renewal as a policy in the city.

The destruction of city centres across North America led to a backlash, Jane Jacobs being among the leaders of this movement. In Toronto, pressure from the public eventually forced Premier Bill Davis to cancel the proposed Spadina Expressway. Nationally, a 1968 Task Force led by Paul Hellyer concluded that between 70% - 80% of the buildings demolished under urban renewal projects could have been rehabilitated. As a result of these findings, Federal financial support of urban renewal projects ended in 1973.

Unfortunately for Lowertown East, it was the final project approved and one of the largest. Despite the efforts of resident committees to oppose the planned renewal, or to modify it, it proceeded without approval from the community. Between 1967 – 1977 there were 462 expropriations in Lowertown East, an estimated 1,400 families were forced to relocate at a cost of $31 Million ($250 Million in 2023 dollars). Among the issues identified by the community were: inconsistent / inadequate compensation, excessive rents in new buildings, the destruction of the French language character of the community, no provisions for elderly residents, an abandonment of a mixed income strategy leading to ghettoization. These concerns remained unaddressed.

There were a couple of positive outcomes of the urban renewal of Lowertown East. The community countered the planned redevelopment through the construction of three cooperative housing projects, the rebuilding of the Catholic Community centre and through the creation of a new French language High School, De La Salle Academy. There were however far more negative outcomes. These included the loss to the community of many of the more affluent and educated members, who fled to the suburbs or other parts of the city, the loss of the Irish and Jewish communities, the closure of the major churches and synagogues, the creation of a transient population who had little control over their own housing, the segmenting of the community by major roadways, the belief that the renewal had been an organized attempt to destroy the main Francophone community and a lingering distrust of municipal politicians and staff. Today, even though the community has regained much of its former strength through such organizations as the Lowertown Community Association, it still finds it difficult to achieve its community goals and finds itself fighting similar battles as it had in the past to preserve its heritage. The battle never ends.

Following Marc’s presentation, we were honoured to have Councillor Stephanie Plante answer a few questions. She promoted the idea of creating a Lowertown Museum, similar to those in other communities which are now part of Ottawa. She also spoke of the need for elected officials to obtain input on policies and programs that will affect them. She emphasized the responsibility of Councillors to seek out this input from those who may not normally provide it, due to their age, language, income or other factors.

Marc has written two books that relate to Lowertown:

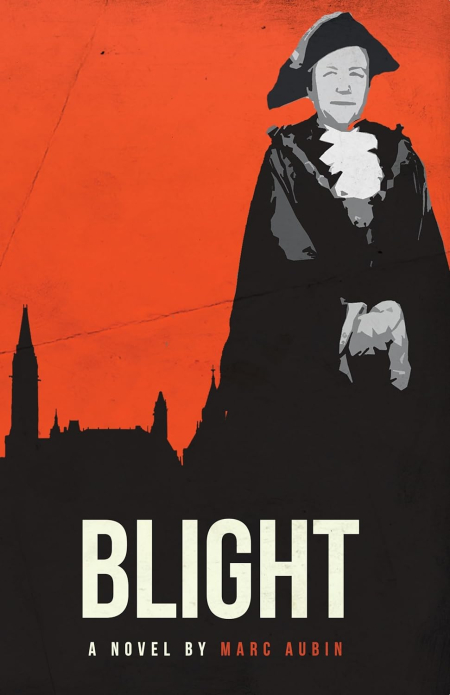

- BLIGHT, published by Crow’s Nest Books in 2018 is a “fictional” account of the struggles of an activist against City Hall. It is available at Blight by Aubin, Marc .

- CUNDELL STABLES, THE LAST STABLE IN LOWERTOWN. (With Karen Bailey)