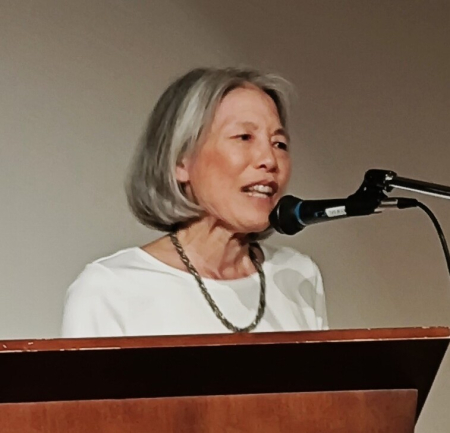

On the afternoon of April 26th, 2025, members of the Historical Society of Ottawa, along with many members of the general public, gathered at the Main Branch of the Ottawa Public Library for the presentation of the 2024 / 2025 François Bregha Storyteller awards. Following the ceremony, the large crowd, numbering some 75, settled in to listen to one of the recipients, Denise Chong, speak to us about many of the aspects of being a non-fiction writer.

Denise Chong, an Order of Canada recipient, is the highly acclaimed author of five non-fiction books. These are: “The Concubine's Children” (1994); “The Girl in the Picture: The Kim Phuc Story” (1999); “Egg on Mao: The Story of an Ordinary Man Who Defaced an Icon and Unmasked a Dictatorship” (2009); “Lives of the Family: Stories of Fate and Circumstance” (2013) and “Out of Darkness: Rumana Monzur's Journey through Betrayal, Tyranny and Abuse” (2024). Prior to her career as a writer and historian, Denise studied economics at the University of British Columbia, later receiving her M.A. from the University of Toronto in 1978. She moved to Ottawa to work as an economist in the federal government and in 1981 became a senior economic advisor to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau until his retirement in 1984.

Denise began her presentation with a brief summary of part of The Concubine's Children, which is the story of her own family. She explained that her grandfather, Chan Sam, came to Canada in 1913 to find work and send money home to his wife, Huangbo, who remained in China. Life in Vancouver was lonely, so in 1924, Chan Sam sent to China for a concubine, a second wife, May-ying, who was 17. They had two daughters together, Ping and Nan, before returning to China. Discovering that she was pregnant again, May-ying sought information from a blind soothsayer and was told that she would have a son this time. Believing that it would be better for their son to be born in Canada, Chan Sam and May-ying left their two daughters in China with Huangbo returning to Vancouver in 1930. Shortly thereafter, a third daughter, Hing, was born to the couple. This was a great disappointment for May-ying. Hing went on to have five children of her own, one of these being Denise.

Denise explained that her interest in her own history had been sparked by a couple of old photos. Her desire to understand the story behind the photos lead to her research, her trip to China, and eventually to the book. A similar thirst was initiated when she was offered an opportunity to do a quick biography of Kim Phuc. She knew, however, that the only way she could write one was to really dig into the full story. Research in countries like China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh is fraught with danger as such governments are not anxious to have challenging stores told ad have the inclination and means to suppress investigation. Denise told us of some of the tricks she has used, such as memorizing the map of a village so she would not look like a tourist or recording her covert research notes in the form of a travel journal and by conducting interviews while walking along public pathways.

Memory, Denise reminded us, is the pond from which the non-fiction writer must try to catch much of their information. Memory can be a flawed source, fragmentary, sometime manipulated, and sometimes contradictory. Different people may have different, but equally valid, memories of the same event and the writer must try to sift out what really took place. Denise pointed out that the act of asking promotes a rethinking of events and that for the most important questions, the initial time asking often yields the least contaminated responses.

Denise spoke to us of how the non-fiction writer uses the story of an individual or a single incident to tell a larger story. As such, the story of one family can represent the history of a community or of a collective experience, the story of one girl can tell the broader story of the horror of war, one man’s act of defiance can reveal an entire culture of oppression and an attack on one woman can expose not only systemic domestic violence but courage and triumph as well.

There are strong parallels in the writing of fiction and non-fiction, Denise explained, the only real difference being that the non-fiction writer does not create their characters and events. Their obligation remains to create a compelling narrative. One of the ways this is done is by inhabiting the characters, walking where they walked, seeing what they saw, feeling what they felt and doing, as much as is possible, what they did. She gave us the example of filling eggs with honey and throwing these against the second storey of her own house so she would have the feel of the egg in her hand and the sense of force and motion of hurling eggs, so she could accurately reflect this in her book “Egg on Mao: The Story of an Ordinary Man Who Defaced an Icon and Unmasked a Dictatorship”.

As Denise concluded her session, she let the audience know the final piece in becoming a successful non-fiction writer. Apart from all the research, work and skill that goes into a book, luck plays a large part. Her publisher had only intended to print a couple of hundred copies of The Concubine's Children, believing that these would sell in and around Vancouver. Instead it became an international best seller, and is now even being adapted for TV in China. The great success of her first book meant that other opportunities were presented to her and her initial success gave her the power to tell those stories in the way she felt they should be told.