Sonja McKay – Zéphérine Brunet, a French Canadian in Bytown

Among the settlers who populated Bytown, many were francophones. By examining the stories of her own francophone ancestors, Sonja McKay reveals a window through which we obtain a glimpse of what life would have been like for many French-Canadians during that era.

Sonja McKay is a retired public servant and social policy analyst, an amateur genealogist, and member of the Historical Society of Ottawa.

Zéphérine Brunet, a French Canadian in Bytown, 1830s-1850s

Among the settlers who populated Bytown between 1826 and 1855, there were many francophones who came from what is now Quebec. Some of them were my ancestors. I will describe the experiences of a few of them in this article.

Many French-Canadians arrived in Bytown to work in the growing lumber industry in the 1840s and ‘50s. As well, some highly-educated French Canadians came to Bytown (e.g. physicians, lawyers, religious officials, business owners and their families). Lucien Brault’s 1941 in-depth thesis on the history of Ottawa recounts that by 1851, there were 2,056 French Canadians in Bytown, out of a total population of 7,760. Over 25% of the population were francophones.

We know too, that the land and waterways around Ottawa had already long supported Indigenous families and nations – notably the Algonquin Anishinabe nation on whose traditional lands Bytown emerged. Bytown was not a beginning for the Ottawa region, but it was the beginning of my personal family history here.

This article tells the stories some of my francophone ancestors and their friends who came to Bytown in the 1830s and ‘40s. A key figure is Zéphérine Brunet, my great-great-grandmother. In learning bits of information about her and her family, we can see a glimpse of what life was like for labouring French Canadians in those days.

A quest to learning about the origins of my grandpère, Adonias Robillard

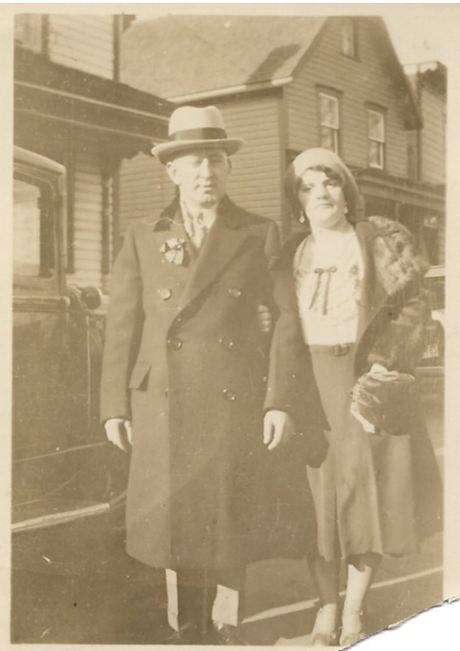

I never met my grandfather, Adonias Robillard, because he died before I was born. Adonias was born in 1893 in Ottawa, and he did metalworking until his death in 1955. My mother, Carmen, remembers him as a kind and loving father. Carmen grew up in a franco-Ontarian family in Eastview (now Vanier). Her mother Eva Létourneau was born near Québec City and migrated to Ottawa with her parents when her father obtained a civil service job in the federal government. The couple married in 1930. My family has few photos of Adonias – one was taken on his wedding day. It shows him dressed in his best outfit, probably standing outside his bride’s home on Friel Street in Lowertown Ottawa.

Figure 1: Adonias Robillard and Eva Létourneau, circa 1930. Photo courtesy Carmen McKay

Figure 1: Adonias Robillard and Eva Létourneau, circa 1930. Photo courtesy Carmen McKay

When I searched for more information about Adonias, I found that both of his parents were born in the Ottawa area (one in Gatineau) and all four of his grandparents were either born in Bytown or moved to the town before 1855.

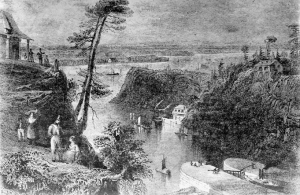

Bytown in the 1830s was in a period of transition from the building of the Rideau Canal in 1826-32 towards becoming a booming lumber town. Between 1835 and the mid-1840s, it seems there were more people than jobs in the lumber industry, and consequently conflict. It’s said that the Shiner’s War between mainly French-Canadian and Irish lumber workers took place then. There was no police force and no jail. What could go wrong?

1830s: Zéphérine Brunet, her family and friends

The earliest of my great-great-grandparents to arrive in Bytown was Zéphérine Brunet. She moved here with her parents in the year 1835, or possibly a year or two earlier, when she was just six years old.

Zéphérine’s approximate year of arrival in Bytown is decipherable because of records of her siblings (and her own) dates of birth and places of birth. The eldest of 9 children were born in St. Eustache (just north-east of Montreal) where her parents had married. Zéphérine and others were born in La Petite Nation (which includes what are now the towns of Papineauville and Montebello on the north side of the Ottawa River). Zéphérine was born in the summer of 1828. Her youngest two brothers were born in Bytown – one in 1835, the last in 1840. So, they were in Bytown by 1835.

Zéphérine’s father, Janvier Brunet, is identified as a “journalier” or labourer in various documents. The family migrated following employment opportunities, with mother Amable and children making a lively home wherever they went. It’s possible Janvier worked mainly in Bytown (rather than away in a lumber shanty), perhaps in a lumber yard, or assisting a merchant in the ByWard market.

The Brunet family knew another family that came to Bytown around the same time – the Brûlés. Both families spent a few years living in La Petite Nation east of Bytown on the north shore of the Ottawa river, a region named in reference to the Indigenous people that already lived there. That region of la Petite Nation was just beginning to be settled by Europeans in the early 1800s. Similarly to Bytown in the 1820s, there was not yet a permanent church or priest assigned to the area. Missionaries would travel to the area every few months. In fact, Zéphérine was not baptized until five months after her birth, probably due to the family’s distance from a priest.

The Brunet and Brûlé families may have held land leases in La Petite Nation, but I found no evidence of this. Possibly they were employed by leaseholders to cut trees, clear rocks or till the soil. Perhaps, once the trees were sold, they moved on. For whatever reason, both the Brunet and Brûlé families moved to Bytown in the 1830s.

My family’s picture starts to become more clear in the 1840s as more records of births, marriages, and deaths appeared in my family tree.

The 1840s

In 1843, a law was passed called the Vesting Act. This made the acquisition of land and establishment of public amenities more feasible in Bytown, where previously the residential lots had been merely available for lease to townsfolk. This encouraged people to invest more in building solid homes.

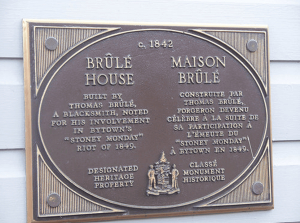

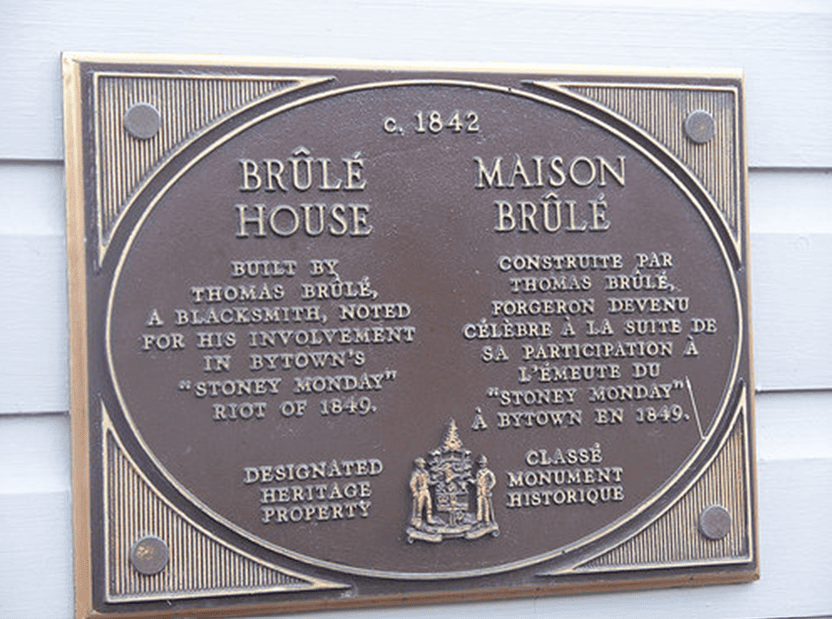

In this context, a still-standing heritage building on St. Patrick Street in Lowertown was built in approximately 1842 by Thomas Brûlé, a francophone blacksmith. Whether he began building it before or after the Vesting Act was passed, it seems likely he would have finished it as an owner of the lot, not just a tenant, as the building was solidly built enough to still stand today. Located at 288-290 St. Patrick Street, the building’s façade sits close to the street, and it has two front doors, indicating it formed two side-by-side homes. Behind the house one can glimpse a paved yard that once might have held a shed for a horse or a pig.

Figure 2: Brûlé House, 288-290 St. Patrick Street, 2024. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

Figure 2: Brûlé House, 288-290 St. Patrick Street, 2024. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

As the Brunet and Brûlé families’ children grew up, well, they got married. Zéphérine Brunet married Edouard Brûlé on July 1, 1846, in Bytown. Edouard was a brother of Thomas, and Thomas served as a witness. The marriage would have taken place in a wooden church, the precursor of today’s Notre Dame Cathedral. (Construction of the cathedral had begun in 1841, and the walls and roof were completed in 1846, but it was not quite ready to host services yet.) Edouard made a living in the logging industry, and may probably have spent significant time away from his wife. They had two daughters by 1849. As I’ll show below, it’s very likely they lived in the Brulé house with Thomas and his family.

As author Michael McBane described in his excellent 2022 book, Bytown 1847: Elisabeth Bruyère and the Irish Famine Refugees , Lowertown was a muddy, crowded place in the 1840s. Most homes were built of wood and the streets were not paved. There was no municipal plumbing or electricity. Many households kept animals such as horses and pigs in their yards, the latter to eat the leftover scraps and to be butchered for food. Cows were allowed to feed on local grass. Land not yet built on served as vegetable gardens in summer. Ice hauled from the river in winter was stored and sold in summer to cool food. Potable drinking water was scarce, and outbreaks of communicable diseases occurred.

Another event of the 1840s is worth noting here: Thomas Brûlé participated in the “Stoney Monday” riot in September of 1849, another violent episode in our city’s past. He and another man were charged with murdering the only person to die that day, but both were acquitted. It turned out no one saw who shot the victim, David Borthwick. The riot had erupted between people of different political views, which had coalesced into a dispute over whether to invite the Governor General to Bytown or not. I imagine the trouble Thomas found himself in worried his family greatly. In the end, he was free to resume his livelihood.

Figure 3: Plaque on Brûlé house 288-290 St. Patrick Street, Ottawa. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

Figure 3: Plaque on Brûlé house 288-290 St. Patrick Street, Ottawa. Photo credit: Sonja McKay

The 1850s – A husband’s death, a new marriage

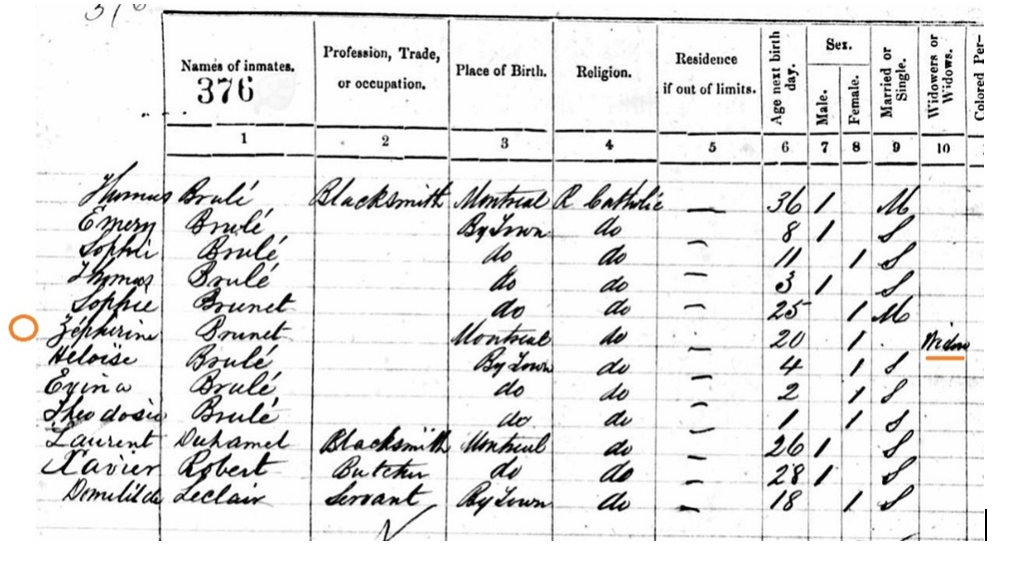

The 1851 census (taken in January 1852) shows that Zéphérine Brunet and her now three young children lived with Thomas Brûlé and his family -- see the orange circle in the census image, beside Zéphérine’s name, followed by her three daughters Heloise, Exina, and Theodosie. This residence must have been the 288-290 St. Patrick Street building, though no street addresses were given on the census. Sadly, Zéphérine was described as a widow. How could this be, I wondered?

Figure 4: Excerpt of 1851 Census showing those living with Thomas Brûlé. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

Figure 4: Excerpt of 1851 Census showing those living with Thomas Brûlé. Source: Library and Archives Canada.

Edouard had died a mere two months earlier, on November 14, 1851. A chilling note on the church register for his burial reads “tué par la chute d’un arbre” – Edouard was killed by a falling tree. It’s mainly because of this note that I assume Edouard worked in logging industry, and this was likely an accident in the forest while felling trees. The notation was written by father Damase Dandurand, a priest who arrived in Bytown in 1848 and who went on to serve the Roman Catholic community for the next 30 years. Thomas Brûlé was a witness to the ceremony.

This sad event had a silver lining, however, at least from my perspective. Edouard’s death paved the way for Zéphérine to remarry and have more children – one of whom became my great-grandmother Joséphine.

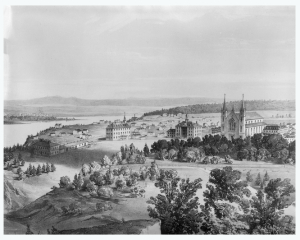

Zéphérine married her second husband, Eugène St. Jean, in Bytown on October 10, 1853. Eugène lived in Bytown, and he was from a town north of Montreal – St. Roch de l’Achigan. Again, the ceremony was performed by father Damase Dandurand, and Thomas Brûlé was a witness. The wedding likely took place inside the new Notre Dame cathedral, as it had been consecrated on September 4, 1853. Though the church’s decorate elements remained to be completed over the coming years, it already stood as solid beacon for the Roman Catholic community in the town.

Figure 5: Notre Dame Cathedral, Ottawa. Photo by Michel Rathwell, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 5: Notre Dame Cathedral, Ottawa. Photo by Michel Rathwell, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The couple had five children together – a son and four daughters. Their youngest child, Joséphine, grew up to become my great-grandmother (Adonias’ mother). By the 1860s, the family had moved to the northern side of the Gatineau River – just across the Ottawa river in Pointe-Gatineau. This is where Joséphine was born in 1866.

Not much is known about Eugène St. Jean other than the interesting fact that he studied classics at the College de l’Assomption between 1839 and 1841 in Quebec. I imagine from this that he may have worked as a clerk or some other occupation which required education. Unfortunately, he too passed away before 1871 when Zéphérine appears in the 1871 census as a widow in Pointe-Gatineau.

Later, Zéphérine moved back to the Ottawa side of the river, showing how closely connected the two sides of the river were (as they are to this day). She married a third time, and lived to the ripe old age of 96.

Conclusion

This story focussed on the Bytown days of my family’s history. As we know, Bytown was renamed Ottawa in 1855, and soon was appointed by Queen Victoria to become Canada’s capital city. My family’s Ottawa story continued until my mother met my father in Ottawa. While I was raised primarily in an English-speaking household, I am proud of my francophone heritage and happy to share some of it with readers.

My heart is filled with gratitude to know that these relatives, and other settlers, survived in Bytown through the help they gave each other. It saddens me to know they also grieved the early deaths of loved ones, but this was common for the time. This story demonstrates in a concrete way how families survived by cooperating and sharing resources, and moving to where there was work. We can glimpse through them, much about what life in Bytown was like for its francophone settlers.

References:

Brault, Lucien (1941). Ottawa: Capitale du Canada de sesorigines à nosjours . PhD Thesis presented to University of Ottawa.

Brault, Lucien (1946). Ottawa Old and New. Ottawa Historical Information Institute. Available at the Ottawa Public Library.

Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française.Vie française dans la capitale. A virtual museum website about Ottawa’s francophone history. Bilingual. https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/ Accessed 2026-02-03.

McBane, Michael (2022).Bytown 1847, Elisabeth Bruyère and the Irish Famine Refugees.Available in bookstores and at the Ottawa Public Library.

Notre Dame Cathedral. https://notredameottawa.com/history . Accessed 2026-02-02.

André Pinard – Première réunion publique bilingue à Bytown

André Pinard takes us back to a pivotal moment in a period of cultural tension in Bytown. Read the story (in French): Première réunion publique bilingue à Bytown

André Pinard is originally from Ottawa's Lower Town. He pursued a career in education in Northern Ontario and the Ottawa region.

Marking Bytown's 200 Anniversary

Many thanks to CTV Ottawa and CFRA iHeart radio for highlighting our bicentennial celebrations planned for 2026.

Watch HSO spokesperson Ben Weiss on CTV Ottawa Morning discuss the Historical Society's bicentennial plans. And stay tuned to the end of the clip to see a 100-year old relic from the centennial celebrations in 1926 to compare civic festivities of yesteryear! Link to Ottawa turns 200 this year video.

Listen to Ben in conversation with Patricia Boal on CFRA iHeart radio: Marking Bytown's 200th anniversary audio clip.

Check out our Bytown 200 story collection: www.historicalsocietyottawa.ca/resources/bytown-200

Bryan D. Cook – William Pittman Lett: Ottawa’s First City Clerk and Bard

William Pittman Lett, who was 13 years old when the Rideau Canal opened, went on to witness and, through his poetry, chronicle the evolution of rough and tumble Bytown into the capital of a nation.

Now, for the first time ever, HSO member Bryan D. Cook’s biography of William Pittman Lett can be accessed digitally: Introducing William Pitman Lett : Ottawa's First City Clerk and Bard 1819-1892 along with Lett’s prolific collection of poetry spanning most of the nineteenth century, including Lett’s iconic “Recollections of Bytown and Its Old Inhabitants”.

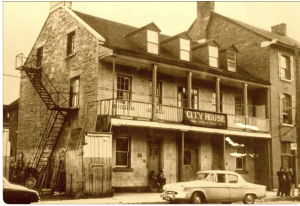

Chateau Lafayette Pre-History (1849-1863) – Ashley Newall

Bytown’s taverns were notoriously abundant in number – but the Chateau Lafayette (“The Laff”) boasts the distinction of being the only of those Bytown era drinking houses to still remain in operation today. Founded in 1849 as “Grant’s Hotel”, Reformers took refuge inside during Bytown’s infamous Stony Monday Riot of that year.

Ashley Newall takes us back to when the tavern known today as the Chateau Lafayette was in the “thick of things” when our city was known as “brawling, rioting, lusting, wenching Bytown”.

Ashley Newall is an Ottawa singer-songwriter-musician and history writer, whose stories can be found his Capital History (CapHistOttawa) social media pages, his ashleynewall.ca website and on Apt613.ca.

Défi Bytown200 de l'HSO: partage une histoire pour le bicentenaire en 2026

Les contributions en français sont les bienvenues!

Aidez-nous à souligner l’année 2026, le 200e anniversaire du début de la construction du canal Rideau et de la fondation de Bytown.

Nous invitons les récits portant sur le canal Rideau ou Bytown (1826-1855), sur l’histoire de la région d’Ottawa antérieure à ces événements, ainsi que sur l’impact de leur établissement sur la vie et les moyens de subsistance des Autochtones.

Toutes les contributions sont les bienvenues. Les textes sélectionnés seront publiés sur une page Web spéciale du site de l'HSO, accessible à tous, y compris aux enseignants. Les contributions admissibles peuvent être soumises sous différents formats, notamment par écrit ou en format audio/vidéo.

Nous espérons également intégrer les contributions sélectionnées aux nombreuses autres plateformes de l’HSO, telles que le blogue de l’HSO, le bulletin Capital Chronicle de l’HSO, les articles et la section « Histoires d’Ottawa » de notre site web, et potentiellement la série de brochures de l’HSO. Tous les textes seront également diffusés sur nos réseaux sociaux.

Visitez la page principale du Le défi de narration du bicentenaire de Bytown200 de l'HSO 2026 pour en savoir plus. Comme pour tout le contenu de notre site web, veuillez cliquer sur le bouton « FR » (en haut de la page) pour la traduction française :

www.historicalsocietyottawa.ca/hso-news/the-hso-2026-bytown200-bicentennial-storytelling-challenge

Visitez la page de notre Collection de récits du bicentenaire de Bytown200 HSO 2026 pour découvrir notre collection de contes en constante expansion :

James Powell – Today in Ottawa's History

James Powell takes us back to the early days of the Rideau Canal and Bytown with stories about the Shiners’ War, the Stony Monday Riot, The ByWard Market, Bytown’s first newspaper, Bytown's journey to becoming Canada's capital... and more.

James is the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History giving a day-by-day account of local history.

The Chaudiere Bridges

One of the most pressing priorities for Lt. Colonel By and his engineering colleagues, was to span a bridge across the Ottawa River in order to transport essential supplies and workers from Wright’s Town urgently needed to begin construction of the Rideau Canal: The Chaudière Bridges, 28 September 1826

The Canal

James shares the story of one of the most remarkable engineering feats of its era – the construction of the Rideau Canal: The Canal, 29 May 1832

The Shiners’ War

For the better part of a decade, lawlessness reigned as Bytown’s citizens were terrorized by violent gangs of thugs known as the “Shiners”, cunningly manipulated by the ruthless and ambitious Peter Aylen, a man willing to fuel religious and linguistic division in his attempt to solidify his own unassailable Ottawa Valley timber empire: The Shiners’ War, 20 October 1835

Ottawa’s First Newspaper

500 copies of Bytown’s first newspaper hit the streets on February 24, 1836. James Powell flips through the pages of that first four-page edition and takes a peek at what its first subscribers would have been reading: Ottawa’s First Newspaper, 24 February 1836

The ByWard Market

James Powell traces the history of Lowertown’s almost two-century old ByWard Market: The Byward Market, 4 November 1838

Corporation of Bytown

John Scott was elected the first mayor of Bytown – twice. Initially incorporated in 1847, with John Scott elected as Bytown’s first mayor, Bytown’s charter was subsequently disallowed following a dispute with the Ordnance Department, the military administration that had become accustomed to being in charge since the days of Lt. Colonel John By. James Powell shares the story of how matters were eventually resolved and how, upon reinstatement of Bytown’s charter, John Scott was, for a second time, elected as Bytown’s first mayor: The Corporation of Bytown, 28 April 1847

Stony Monday Riot

In 1849, the Stony Monday Riot erupted in Lowertown between the Reformists and the Tories. Dozens of injuries and one death resulted when as the (mostly Protestant) Tories, furious over the impending visit of the Governor General, Lord Elgin, clashed with the (largely working-class Catholic) Reformists: Stony Monday Riot, 17 September 1849

Lord Elgin Visits Bytown:

Remarkably, Lord Elgin’s visit in 1853 -- only four years after the Governor General had been forced to cancel his visit following Bytown’s violent Stony Monday Riot -- resulted in Lord Elgin’s recommendation that Bytown to be chosen as the Province of Canada’s new capital: Lord Elgin Visits Bytown, 27 July 1853

Choosing Canada's Capital

Toronto, Kingston, Hamilton, Montreal and Quebec City were among Bytown’s rivals in the intensely-fought contest be chosen as the Province of Canada’s new capital. Bytown even went so far as to change its name to “Ottawa” in hopes of distancing itself from its (well-earned) reputation as a violent and uncivilized backwoods lumber town. James Powell retraces Bytown’s surprising journey to becoming Queen Victoria’s unexpected choice as Canada’s new capital: Queen Victoria Chooses Ottawa, 31 December 1857

Ottawa’s Centenary

In celebration of Bytown’s 100th anniversary in 1926, the Ottawa Journal published an article predicting what Ottawa might be like a century later, in 2026. Today, as we mark the 200th anniversary of the founding of Bytown, James Powell takes us back to 1926 for a look at those predictions and at how else our city celebrated our centenary: Ottawa’s Centenary, 16 August 1926

Richard Collins – The Evil that Men Do

Richard Collins joined HSO in 2018, when he moved to Ottawa. Although his heritage walking tour business has sent him back to the GTA, he remains part of HSO, as the newsletter editor.

Richard recounts how canals have evolved, in Ottawa and elsewhere.

If Shakespeare had been around to write an article for HSO’s 2026 Bytown200 Bicentennial Storytelling Challenge (stiff competition for the rest of our contributors), two characters would have played a prominent role.

Ottawa, 1910

The scheme devised by the two antagonists was there in plain text, on the front page of the Ottawa Citizen, complete with portraits of the perpetrators displayed prominently. The two had come to Ottawa, from CPR’s home base in Montreal, not to praise the Rideau Canal, but to bury it.

Thomas Shuaghnessy was president of Canadian Pacific, and his general manager (and brainchild of the plan) was David McNicoll. (The town of Port McNicoll, on Georgian Bay, is named in his honour, although in Port McNicoll’s case, he was a proponent of marine transportation; not an opponent of it, as we was with the Rideau Canal.)

The part played by the Ottawa Citizen was to help it’s readers understand the logistics, for better or worse, behind Canadian Pacific’s logic to drain the Rideau Canal, pave the basin and lay railway tracks along the razed waterway to a new station that Grand Trunk had recently proposed to build beside the east bank of the canal, on the south side of Rideau Street.

Welland, 1972

I was eleven when I heard of similar news about the canal in my hometown. The province’s Department of Highways had put forward a plan to drain the soon-to-be abandoned section of the Welland Canal through its namesake city and build in the channel a new high-speed highway to whisk people efficiently from the QEW to the frantic urban centre of metropolitan Port Colborne – a city that, even today, hardly warrants a 400-series highway. (No disrespect to the people of Port Colborne – I have two cousins there – but the town has only 20,000 people.)

At Queen’s Park, opponents of the Ministry of Transportation’s plans were skeptical. The residents in Welland were furious. As a kid, I was just confused. Like the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, Welland’s man-made waterway was the historical and spiritual heart of a city that owes its very existence to the canal. Why would anyone want to take that away?

Ottawa, 2018

While leading a walking tour of the locks at the base of Parliament Hill a few years ago, I was asked by a man from Thorold about which of the two canals is the older; the one we were touring or the one in his backyard. The answer is a bit convoluted. William Hamilton Merritt completed the Welland Canal in 1829; three years before the Rideau Canal opened. But that canal was almost entirely destroyed through the 1850s when the Province of Canada Board of Works (the predecessor of the same department that contemplated the Rideau’s fate, in 1910) gradually replaced that first canal with a wider one, with bigger locks; naturally using the path of the existing canal. (Part of historic Lock 5 is still there, but you have to blaze a trail through bush to get to it. The ruins sit underneath Highway 406.) Yet, against the odds (and, as we’ll see, the wishes of Canadian Pacific), the Rideau Canal remains today, and still in use, as it was nearly 200 years ago. The size of the locks is the same now as the day Colonel John By approved the paperwork for their construction. This makes the Rideau the oldest surviving canal in Ontario.

The current Welland Canal is its fourth, and largest, iteration. The Welland locks make the Rideau’s locks look like teacups. (The three continuous locks at Thorold – Locks 4, 5 and 6) are three times the length of all eight adjacent locks in Ottawa.) It’s fascinating to watch ocean-going ships climb what is essentially the engineered equivalent of Niagara Falls (11 km to the east) but still, the Welland Canal lacks the charm and the heritage of the Rideau Canal.

Mississauga, 2025

(I hope my relatives in Welland don’t read this.)

Ottawa, 1910

When he took over as CPR’s general manager in 1903, McNicoll went on a mission to correct the mistakes he felt Ottawa’s earliest railway had made when building their line into Ottawa; something that his 1910 plan intended to correct.

The earliest of these – the Ottawa & Prescott Railway (by 1910, it was CPR’s Sussex line) – chose a terminal near the mill complexes at New Edinburgh. This alignment secured a lucrative source of freight tonnage, but left passengers bound for central Ottawa well east of their destination; with a long horsecar connection back into town. Fifteen years later a second line into Ottawa – the Canada Central (CPR’s Ellwood line, in 1910) – established a terminal at LeBreton Flats. It was also a good source of freight traffic, but this time passengers were trapped well west of the city centre, and a horsecar ride into town.

Meanwhile, CPR’s competition – Grand Trunk – had already chosen a route into Ottawa, along the east side of the Rideau Canal, that brought its trains right into the heart of city; just a few blocks away from Parliament Hill. McNicoll could have considered the option of sharing GTR’s line, but that meant writing monthly rent cheques to the competition. The better plan, in McNicoll’s view, was to pay one flat fee to buy the Rideau Canal from the Dominion government and use its right-of-way into the city centre. Misleading tales of summertime cholera outbreaks from stagnant canal water, or ice jam-induced spring floods, or military obsolescence, or declining traffic were all part of McNicoll’s pitch to diss the canal and motivate the seller.

The canal path was necessary to get passengers into central Ottawa from a line CPR had built on its own, in 1898 (the M&O Line), to be the shortest, fastest way between Ottawa and Montreal. The proposed Rideau Canal connection would also be the fast way west, to Toronto, too. To link the nation’s capital to its two biggest cities (something GTR had already done), McNicoll needed the canal’s right-of-way, come hell or stagnant water.

Rochester, 1908

McNicoll’s plan to drain the Rideau Canal and encase it in a concrete straitjacket was monumental, but not unprecedented. CPR’s plan for Ottawa had an an eerie (if you’ll allow the bad pun) similarity to events taking place in Rochester, New York.

Construction began two years earlier on a project to direct the Erie Canal south of the city. In the meantime, even while the old canal through the city was still in use, Rochester’s city fathers were drafting plans to drain the soon-to-be disused section and convert it to a subway (sort of) to give the city’s streetcars – inbound from the suburbs – a car-free path downtown. (The original Erie Canal is older, although only by a few years, than either the Welland or Rideau.) Looking through editions of the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle from that period, there seems to have been little opposition to removal of the historic canal. I guess it wasn’t really all that historic at the time. Heritage preservation wasn’t as strong an initiative in 1910 as it is today. Lift bridges, seemingly more often up than down (something I remember from my youth) delayed traffic, but residence, and D&C’s editor, seemed to welcome the canal’s end.

But Ottawa’s a different story.

Ottawa 1910

Opposition was strong here. That is to say that there was unity in Ottawa between residents, businesses and local politicians, to save the Rideau Canal. The position itself was weak.

The only case the community had, to stop CPR from moving ahead with its plan, was the cultural heritage defense. Long before Queen Victoria selected Ottawa as the capital of Canada, the Rideau Canal planted the seed that geminated into a city. It was seminal, it was scenic, it was serene. But by 1910, the Rideau Canal had become nearly useless.

CPR’s defense for its railway plan was that the Rideau Canal had outlived its purpose. McNicoll declared that public opposition to the closing of the Rideau Canal was “a matter of sentiment, not business.”

Frustratingly, McNicoll was right. Traffic had been on the decline on the Rideau Canal for over a decade. The Ottawa Journal (an opponent of CPR’s plan) commented on a report by the Department of Railways and Canals which seemed to state that there had been a “substantial increase” in marine traffic on the canal, and that passages in 1909 had been the highest in 15 years.

But that statement was a bit misleading, whether by choice or by ignorance. It’s true that traffic had been up on the “Ottawa District” of the the Department’s network, but that geographic district also included the tonnage stats for the Carillon Canal and Grenville Canal (the chain of locks and channels along the Ottawa River, eastward to Montreal) since all tonnage passing through these two canals, as well as the Rideau, north of Smith’s Falls, was reported to the Ottawa office of the Department of Customs and Excise. More than two-thirds of the district’s registered tonnage traveled through the Ottawa River canals; not the Rideau Canal.

Passenger traffic through Ottawa (Locks 1 to 8), Hartwells (Locks 9 and 10) and Hog’s Bank (Locks 11 and 12) in 1909 was down to 19,498 passages from a 1905 peak of 24,394.

It’s easy to play with the numbers, and McNicoll did. Annual traffic flow on the Rideau Canal typically, unpredictably, rose and fell frenetically over the years, like mercury in an Ottawa thermometer in springtime. Good harvests or bad on Ottawa Valley farms – alone of all other commodities shipped on the canal – could adjust the number of freight passages by integers, year by year. A busy year of road construction could send aggregates tonnage up that year, followed by a season with no tonnage at all, once the new roads projects were completed. Even in recent memory, a global pandemic slashed traffic on the recreational canal. And just when recovery seemed in sight, traffic flow was stalled by rising gas prices, which sent boaters looking for a cheaper pastime, in the meantime. Using Covid-era lingo, business on the Rideau Canal has always been ‘hardwired’ to the unpredictable economy around it. The numbers favoured CPR in 1910, but what of the future?

If the data was open to interpretation, and sudden change, McNicoll had stronger defenses. He claimed that the Rideau Canal no longer served any strategic need. This statement is true, but like the commercial traffic, McNicoll’s military claim is also a bit on the misleading side.

Bytown, 1826

McNicoll hesitated to note that the naval traffic that was supposedly down had, in fact, never been “up”. The Rideau Canal was not a vital link in Canada’s military defense strategy. Of course, one reason for that is the fact that the canal opened 18 years after Canada’s last war with the US. And if war were to flare up again, the possible quick capture of Kingston (the southern entrance into the canal) by the Americans would quickly turn the canal from a strategic defense for Canadians into an effective invasion route for Americans, with the canal’s other end being the primary target the invaders’ advance; Canada’s seat of government.

It wasn’t Britain’s might that Canada was looking for in building the Rideau Canal. They needed the army’s experience. The well-established chain of command of the British Army was essential to progress and completion of such a demanding project. The men of the Corps of Royal Engineers and the Royal Sappers & Miners had the skills to build a canal. Blasting through granite required expertise with explosives; which made the Royal Regiment of Artillery the right appointment for the task of building dams. And with nearly 250 years of empire on its CV, the project overseer – the British Ordnance Department – could shame amazon.com when it came to logistics. If the canal were to be built today, contractors with a wide array of logistical skills would make a bid for the project but the army got the Rideau Canal contract because there were no private contractors in Upper Canada in 1826. (A recent project to naturalize the former Cuyahoga Canal in Cleveland was undertaken by the United States Army Corps of Engineers because the army outbid the private competitors.)

Ottawa, 1910

Not that any of this history mattered to McNicoll. He hadn’t come to Ottawa to convince the locals. He needed to convince the politicians that destroying the Rideau Canal was good for the home field. The city would certainly feel the effects hardest, whichever way Parliament chose, but either way, the feds had the final decision. A wrong decision could make it the governing party’s Waterloo.

Waterloo, 1815

Wellington is a name associated with victory, but that same name proved to be McNicoll’s downfall.

Ottawa, 1910

If sending the last drops of Rideau Canal water down “The Wash” (today, the alignment of King Edward Avenue) and over the Rideau Falls wasn’t enough to raise concern, then digging a tunnel under Wellington Street from the Sappers’ Bridge to CPR’s existing station in Lebreton Flats raised a few eyebrows. This was the expensive chapter in McNicoll’s plan, and it seemed so unnecessary. If only McNicoll could let go of his contempt for Grand Trunk and share the station it was building across from (and along with) the Chateau Laurier, then the cost of the Wellington tunnel could have been avoided, and CPR’s passenger wouldn’t still be stuck in the outer reaches of civilization (Lebreton Flats) waiting for a streetcar connection to the Chateau Laurier.

If McNicoll had let go of the weak part of his plan, the rest of it might have come to pass. (McNicoll died six years later. His successor, Edward Beatty arranged to share GTR’s tracks east of the canal, and its central station in 1920.)

Utrecht, 1969

What would Ottawa be like today if CPR had had its way, and the Rideau Canal was no longer the cultural artery in a city with many historic veins? Utrechtites (or whatever you call people from Utrecht) asked that same question 50 years ago. Canals had been coursing the flat terrain of the Netherland centuries before the first one was built in Canada, but a canal in Utrecht was drained in 1969 to build an eight-lane highway through the centre of the city. After a generation of regret (and declining population in the once trendy Binnenstad district) the people of Utrecht decided they wanted their canal back.

It was a double-whammy defense for canal restoration in Utrecht. The Dutch love their heritage and they’ve grown to hate their highways. Voters demanded a new master plan for the city which (in addition to more cycling paths instead of roads) placed a focus on restoring the Catharijnesingel (the Dutch also love long words) and installing recreational amenities alongside the restored waterway. Conversion started in 2015 and was completed in 2020.

The Catharijnesingel canal started out 800 years earlier as a defensive moat at the perimeter of the old city, but was widened in small stages through the 1810s an ’20s. Like the Erie diversion around Rochester, the Catharijnesingel supplanted the Oudegracht (“old moat”) to the east, which ran through the centre of old Utrecht, but which had become too hemmed-in to be widened to meet the requirements of larger boats; like the original canal through Rochester. So, while Americans were building the first large canal on this continent, ancient Utrecht got a new canal and kept its old one as a scenic feature of the old downtown. Now that’s civic devotion to canals.

Ottawa, 2026?

If McNicoll had gotten his way in 1910, would support in Ottawa to restore the Rideau Canal be as strong today as it was in Utrecht, 20 years ago? I’m inclined to believe that Ottawa folk love the canal they have . . . because they have it. But experience tells me that they’d miss the railway (and mostly roadway) access that would have to go to bring the Rideau Canal back to life, so long after its 1910 demise. (Or, let's say “1920 demise”, given the amount of time it takes the government to decide anything . . . which was, incidentally, McNicoll’s biggest concern in 1910.) In my past walking tours, every time I mentioned the possibility of closing Colonel By Drive, parallel to the canal, to put back the railway tracks that were there up to 1966 (so that trains could reach the “re-repurposed” Grand Trunk station – currently the home of the Senate), the response from those on my tours usually ranged from cautious consideration to rabid rejection.

Unlike Shakespeare, who left you no doubt when his play was coming to an end by killing off all the characters, I’ll leave the conclusion of this story on the near-death of the Rideau Canal to you by asking you what I asked the people on my tours. Would you be willing to sacrifice Colonel By Drive to bring trains back into the city centre. And . . . if Canadian Pacific had succeeded in 1910, would you be willing to sacrifice the roads and rails that were put in its place to get back a long-forgotten canal?

uOttawa CRCCF – Vie Française dans la Capitale

The goal of French Life in the Capital is to tell Canadians an untold Ottawa story about the participation of Francophones in building the nation's capital. An outcome of Chantier Ottawa, an initiative coordinated since 2011 by the Centre de recherche en civilisation canadienne-française (CRCCF) with the participation of over fifteen French Canadian specialists, the exhibition presents archival documents of diverse origins about Ottawa’s Francophone population, its institutions, its achievements, and its ambitions at various times in its history.

Join us in exploring the role of the Francophones in early Bytown, with these excerpts from the University of Ottawa’s excellent “Vie française dans la capitale” website:

Bytown and its First French Canadians

https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/espace/bytown_and_its_first_french_canadians-eng

Lowertown’s First Resident

https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/espace/lowertowns_first_resident-eng

From Loggers to Merchants

https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/espace/loggers_merchants-eng

First Families

https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/espace/first_families-eng

Religious Beginnings in Bytown

https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/espace/first_families-eng

A Political Space is Born

https://www.viefrancaisecapitale.ca/pouvoir/political_space_born-eng

Kevin Ballantyne – Peter Aylen & The Shiners’ War

As part of his “Forgotten Ottawa” series of short video presentations, Kevin shares the story of the “Shiners”, whose reign of terror held the residents of early Bytown in their grip for almost a decade: www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6AzE8AhMsM