Exercise Tocsin B-1961

13 November 1961

Tensions had been mounting between the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact partners and the United States and its NATO allies. In April 1961, some twelve hundred Cuban exiles, backed by the CIA and supplied with American arms and landing craft, had made a failed attempt to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs and topple Fidel Castro. The Cuban Communist leader had come to power two years earlier after having deposed Fulgencio Batista, the corrupt and repressive, American-supported dictator.

The following month, Canada tested its civil defence plans in the event of a nuclear war. In cities across the country, the wailing of more than two hundred sirens warned Canadians to take cover. The Canadian Emergency Measures Organization issued a booklet to households indicating what they could do in the event of a nuclear attack. Called The Eleven Steps To Survival, Canadians were told:

Step 1: Know the effects of nuclear explosions

Step 2: Know the facts about radioactive fallout

Step 3: Know the warning signal and have a battery-powered radio

Step 4: Know how to take shelter

Step 5: Have fourteen days emergency supplies

Step 6: Know how to prevent and fight fires

Step 7: Know first aid and home nursing

Step 8: Know emergency cleanliness

Step 9: Know how to get rid of radioactive dust

Step 10: Know your municipal plans

Step 11: Have a plan for your family and yourself

In the introduction to the booklet, Prime Minister Diefenbaker stated: Your personal survival can depend on you following the advice that is given and the survival of many others may depend on how well you have heeded the advice contained therein. The government also provided plans on how to build a backyard bomb shelter.

Mid-August, East Germany began the construction of the Berlin Wall cutting off West Berlin by land, and denying an escape route to the West by East Germans seeking freedom. In early September, the U.S. military detected four, above-ground Soviet nuclear explosions. Subsequently, radioactive fallout, 320 times higher than background radiation levels, was detected in Ottawa. Federal Health Minister Jay Monteith warned that should such high levels of radiation be maintained, they “could well be a hazard to health.” At a state banquet in Moscow, Indian Prime Minister Nehru told Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev that it would be stupid to start a war. Khrushchev replied that the Soviet people did not want war but “could not look on calmly while Western powers make military preparations on a hitherto unparalleled scale.” With war rhetoric rising, Prime Minister Diefenbaker warned Canadians in early November that “war is not as improbable as we hope,” and that if comes, Canada will be a battleground. Earlier he had told the House of Commons that should there be an attack on Canada, he and his wife would not leave Ottawa for safety but would rather take cover in the bomb shelter at 24 Sussex Drive.

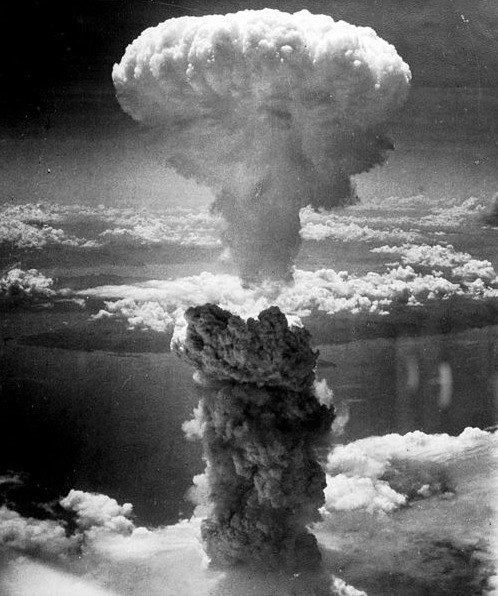

Atomic bomb explosion over Nagasaki, Japan, 9 August 1945, taken by Charles Levy

Atomic bomb explosion over Nagasaki, Japan, 9 August 1945, taken by Charles LevyDuring the morning of Monday, 13 November 1961, unidentified but presumed hostile submarines were detected in large numbers in the North Atlantic and in the Hudson Bay. Soviet tanker aircraft were also detected near the Aleutians. The Canadian armed forces increased it level of military alertness at 8.30am EST. This was stepped up to the next level at 10.30am and yet again at 12.30pm, sending staff to emergency centres across the country. Troops left possible target areas. At 2.30pm, key government officials and senior defence officers, including Defence Minister Douglas Harkness, Health Minister Monteith, Defence Production Minister Raymond O’Hurley, and Justice Minister Davie Fulton, were dispatched to Camp Petawawa, 150 kilometres north-west of Ottawa that was to become the government back-up centre in the event of war. (The underground, bomb-proof base in Carp now known as the Diefenbunker, which was designed to shelter the Governor General, the Prime Minister, and other senior government and military leaders in the event of nuclear war, was still under construction.)

At 6pm, the Canadian military was placed on maximum alert. Shortly afterwards, NORAD (North American Air Defense Command) radar spotted 36 hostile airplanes heading towards Canada between Greenland and Ellesmere Island. Another 20 were detected off the Aleutian Islands in the Pacific. At 6.50pm, Prime Minister Diefenbaker and six Cabinet colleagues went underground at 24 Sussex Drive where they issued an Order-In-Council invoking the War Measures Act. Defence Minister Harkness was appointed Acting Prime Minister and given almost dictatorial powers to respond if necessary. Diefenbaker also approved the signal to alert unsuspecting Canadians to the deteriorating military situation and to take shelter. He also prepared to address the nation across all radio and television stations in a special broadcast of the Emergency Measures Organization.

At precisely 7pm, more than 500 sirens from coast to coast, 45 in Ottawa alone, began a steady three-minute wail, their strident call telling citizens that a nuclear attack was expected. By that point, more than 110 “penetrations” of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line in Canada’s far north had been detected as Soviet bombers streaked across Canadian territory at 600 knots per hour. At 7.10pm, the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) gave Diefenbaker a fifteen-minute warning that a missile attack was underway. Air raid sirens across the country gave the “take shelter” warning, a three-minute rising and falling sound that announced a nuclear strike was imminent.

It total, two waves of Soviet bombers, the first of 150 aircraft, the second of 110 as well as two waves of missiles, mostly heading for U.S. targets, were detected. Fourteen Canadian cities were destroyed by five-megaton nuclear bombs, including Vancouver and Courtney in British Columbia, Edmonton and Cold Lake in Alberta, Fort Churchill, Manitoba, Frobisher, NWT, North Bay, Sault Ste Marie, and Welland in Ontario, Chatham, New Brunswick, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Goose Bay in Labrador, and Stephenville on the Island of Newfoundland. Ottawa was destroyed at 10.10pm, with the epicentre of the blast situated just north of Uplands Airport. Toronto and Montreal were hit at 10.45pm and 10.51pm, respectively. The Soviet attack on North America lasted until 4am the next morning. Some 30 U.S. cities were destroyed, including Detroit, hit by a ten-megaton bomb that also killed tens of thousands in neighbouring Windsor.

The corner of Sparks Street and Elgin Street, Central Post Office, c. 1961, before and after a nuclear attack on Ottawa, Canada Emergency Measures Organization, Government of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4717891 and 4717352.

The corner of Sparks Street and Elgin Street, Central Post Office, c. 1961, before and after a nuclear attack on Ottawa, Canada Emergency Measures Organization, Government of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4717891 and 4717352.

The death toll was staggering. The Army Operations Centre at Camp Petawawa estimated Canadian dead at roughly 2.6 million, including Prime Minister Diefenbaker, with an additional 1.6 million injured, many critically. Fire, radiation sickness, and exposure was expected to claims hundreds of thousands of additional lives in coming days and weeks. In the Ottawa region, the death toll was placed at 142,000 dead, 61,000 injured and 30,000 experiencing radiation sickness. On the upside, 90,000 people had been rescued though many thousands remained trapped in burning buildings and debris. Emergency teams of soldiers and hundreds of thousands of volunteers fanned out across the country to help the survivors. Jack Wallace, the Deputy Director of the Emergency Measures Organization noted that while the Saint Laurence Seaway system had been knocked out at Montreal, Welland, and Sault Ste Marie, the railway service could be quickly restored. While casualties were high, over 14 million Canadians had survived the multiple attacks. He also estimated that one half to two-thirds of industry could be quickly made operational and one-half of hydro power was still in commission. There was also sufficient food to feed all Canadians. Canada had come through the nuclear attack severely damaged but intact, with a nucleus of a national government still functioning at Camp Petawawa where fallout was considered light.

Thankfully, this horrific scenario was just that…a scenario called Exercise Tocsin B-1961 that played out on 13 November 1961 as part of Canada’s test of its emergency civil defences. However, all the events described leading up to the test are factual. While the test may seem fanciful to today’s Gen. “Xers” and Millennials, for those who grew up in the 1950s and 60s, it was very real. The Cold War was a time of great worry and stress. Exercise Tocsin B-1961 was held exactly one year before the Cuban missile crisis when the world held its breath as the United States and the Soviet Union played a high-stakes game of “chicken,” where one false movement by either side could have led to a global nuclear holocaust.

Sources:

Canadian Civil Defence Museum Association, “Steps to Survival,” http://civildefencemuseum.ca/.

Emergency Measures Organization, 1961. Eleven Steps to Survival, Ottawa: Queen’s Printer.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1961. “Tocsin B Alarm Goes Off Accidentally In Ottawa,” 13 November.

————————-, 1961. “Nuclear War Test: PM Among ‘Casualties’ As Toll Tops 3-Million,” 14 November.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1961. “Stupid To Start War Nehru Tells Khrushchev,” 7 September.

————————–, 1961. “Don’t Want War,” 7 September.

————————–, 1961. “War Not Impossible, PM Warns,” 10 November.

————————–, 1961. “Attack Warning Study Alarms Inside Buildings,” 13 November.

————————–, 1961. “Exercise Tocsin, Ottawa ‘Destroyed,’ 175,000 Toll.

————————–, 1961. “Cabinet Met Underground,” 15 November.

————————–, 1961. “Government Counts Tocsin Toll,”

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Tunney's Pasture: The Story Behind Ottawa's Field of Dreams

Join Dave Allston as we take a look at the history of Tunney's Pasture.

Tunney’s Pasture - The Story Behind Ottawa’s Field of Dreams

If there’s one area of Ottawa that seems devoid of history, it’s easy to imagine Tunney’s Pasture being that place, but our September 29th guest speaker, Dave Allston managed to add some humanity to the story of an area famous for its dehumanizing buildings and wide, vacant parks. Tunney’s Pasture has a much richer history than you might expect.

Dave is a long time resident of Ottawa’s west end, and maintains a website, The Kitchissippi Museum, dedicated to telling the stories of communities like Hintonburg, McKellar Park, and Britannia.

A number of developers in the early decades of the 1900s had dreams of building neighbourhoods in Tunney’s Pasture but these failed. A few factories moved into the area, close to the railway tracks, but otherwise the area remained as its present name suggests: acres and acres of pasture. When a small community finally did develop during the Depression it was an isolated collection of shacks, forgotten by following generations. These homes remained in dwindling numbers until the late 1950s when they were finally removed by the federal government when the office development went up. Dave’s presentation included some touching photos of the poor families that managed to eek out an existence in homes without heat, electricity, and running water. At a time when even Ottawa’s finer neighbourhoods were suffering through a deep Depression, the residents of Tunny’s Pasture had a particularly sad tale to tell. Yet as Dave noted in his presentation, the people in his collection of rare photos all seem to be smiling.

It makes you think that perhaps Tunney’s Pasture was not so bad a place at all. Certainly Dave’s presentation proved that Ottawa’s enclave of office towers has an interesting past.

Visit Dave’s website at kitchissippimuseum.blogspot.com for more stories about Tunney’s Pasture and of Ottawa’s other west end communities.

Check out the HSO YouTube channel for a video of Dave's full presentation.

Queen Victoria Chooses Ottawa

31 December 1857

Almost everybody knows that Queen Victoria selected Ottawa as Canada’s capital. But few are aware that the city’s selection was anything but a genteel affair. In fact, the Queen was only asked to help after years of sterile political wrangling between contending factions in Parliament. There were more than 200 votes on the issue. Even after the Queen had made her choice, it didn’t go down well with some and was challenged in Parliament. At the end of the day, Canadian legislators only narrowly ratified the Queen’s decision; a change of three votes from yea to nay would have nixed it.

It all began with the merger of Upper and Lower Canada to create the united Province of Canada in 1841 consisting of Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec), each equally represented in Parliament, under the joint leadership of a premier from each of the two Canadas. The Governor-General, Lord Sydenham, convened the first opening session of the united parliament at Kingston on 14 June 1841. While Kingston residents were delighted to be living in the de facto capital of Canada, others were less enamoured with Lord Sydenham’s choice. Canada East representatives had hoped that either Quebec or Montreal would have been chosen as both were far larger in population and had more to offer in the way of amenities for debate-weary members of parliament. However, Canada West was insistent on hosting the new capital. As Kingston satisfied Canada West’s requirement, Canada East representatives reluctantly acquiesced on the grounds that at least it wasn’t Toronto.

But Toronto-area MPs weren’t satisfied either. They submitted a bill calling for Parliament to meet alternatively in the old capitals of Toronto and Quebec City. This bill passed though the outcome satisfied few. MPs agreed in 1842 to examine three resolutions each favouring a different city as the permanent capital—Montreal, Toronto, or Bytown, as Ottawa was then called. All motions were defeated, with Bytown receiving the fewest votes, only 6 for against 57 opposed.

In 1843, Canada’s Attorney General moved that Montreal be chosen as the capital. This motion passed on a vote of 55 to 22. Toronto and Quebec City were rejected as being too far from the geographic centre of the newly united Province of Canada. Bytown too failed despite its favourable geographic attributes—it bordered both provinces, was pretty much equidistant between Toronto and Quebec, and was located at the mouth of the militarily important Rideau Canal, safely distant from the United States. But politicians and bureaucrats looked in horror at the idea of decamping to an isolated “Arctic lumber village,” with a population of perhaps 5,000. Its tumbledown wooden buildings offered few creature comforts, especially in the midst of a harsh Canadian winter. Cosmopolitan Montreal was a far better choice. There, public servants could enjoy the social and commercial attractions of a well-established city that boasted a population ten times that of Bytown. It was also located on the St. Lawrence, Canada’s vital trade route to the Atlantic.

In November 1844, after months of renovations to St. Anne's Market to accommodate Parliament, the capital moved from Kingston to Montreal. Montreal had seemingly won the day. However, less than five years later, Montreal blotted its copy book when a mob protesting the passage of the Rebellion Losses Act that compensated “rebels” as well as “loyalists” for property destroyed in the 1838 Rebellion burnt down Canada’s Parliament buildings. Reconvening in Toronto, politicians decided against returning to unstable Montreal and instead agreed once again that Parliament would alternate between Toronto and Quebec City. This was a patently nutty decision given the difficulty and cost of moving Parliament and its supporting bureaucrats and files every few years—the Grand Trunk Railway linking Toronto to Quebec had yet to be built.

In 1854, Sir Richard Scott, the mayor of Bytown and later member of the Legislative Assembly for Ottawa, renewed the campaign to make Bytown the capital. In 1856, Canada’s Attorney General moved for a definitive selection of a permanent capital. MPs were given a choice between Toronto, Hamilton, Quebec, Montreal, Kingston, and newly re-named Ottawa. In a veritable blizzard of motions for and against each city, Quebec City emerged the victor by a vote of 64 to 56. The lower house also voted in favour of providing £50,000 ($250,000) to fund the construction of new legislature buildings. Unfortunately, the Legislative Council (equivalent to today’s Senate) refused to support the funding. No funding meant no capital for Quebec City.

The political impasse continued into 1857. In a series of motions, Ottawa garnered only 11 supporters out of a 130-member house though no other city could attract a majority. To break the impasse, a resolution asking Queen Victoria to make the choice passed the Legislative Assembly, though only over stiff opposition by members who considered royal mediation as undermining the Canadian government’s newly-gained responsibility for domestic affairs. The mayors of Toronto, Montreal, Ottawa, Kingston and Quebec City subsequently received letters from the Governor-General, Sir Edmund Head, asking them to prepare papers setting out their respective cities’ merits.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1854. Photo by Roger Fenton.This set in motion feverous activity in candidate cities. In Ottawa, the City Council set up a special meeting of leading citizens, including Sir Richard Scott and Mr. R. J. Friel, to draft a memorial to the Queen setting out Ottawa’s many advantages. Other cities did likewise. Kingston, Montreal and Quebec also sent delegations to London to lobby for support. In the end, Ottawa won the day, a choice favoured by the Governor General. Some say that Ottawa also received unofficial support from Lady Head, the G-G’s wife, who apparently was a good friend of the Queen. The story goes that the Heads had been invited to a picnic lunch in Ottawa held at what would later become Major’s Hill Park. Enchanted with the area and its wonderful river views, Lady Head, an amateur watercolourist, made a number of sketches that she shared with the Queen. Ottawa apparently had other high placed supporters, including Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s Consort.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1854. Photo by Roger Fenton.This set in motion feverous activity in candidate cities. In Ottawa, the City Council set up a special meeting of leading citizens, including Sir Richard Scott and Mr. R. J. Friel, to draft a memorial to the Queen setting out Ottawa’s many advantages. Other cities did likewise. Kingston, Montreal and Quebec also sent delegations to London to lobby for support. In the end, Ottawa won the day, a choice favoured by the Governor General. Some say that Ottawa also received unofficial support from Lady Head, the G-G’s wife, who apparently was a good friend of the Queen. The story goes that the Heads had been invited to a picnic lunch in Ottawa held at what would later become Major’s Hill Park. Enchanted with the area and its wonderful river views, Lady Head, an amateur watercolourist, made a number of sketches that she shared with the Queen. Ottawa apparently had other high placed supporters, including Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s Consort.

The Queen received all the documents by October 1857. After reviewing the material sent to her and consulting with her advisers, she selected Ottawa. Her decision was officially relayed to Canada’s Governor General by Henry Labouchere, the Colonial Secretary, in a letter dated 31 December 1857.

This did not end the debate, however. A motion asking the Queen to reconsider her decision was introduced in July 1858 by the opposition led by The Globe newspaper’s radical editor George Brown. The opposition motion passed the House by a vote of 64 to 50. Then things got really weird. The defeated Conservative-led government of John A. Macdonald and George Étienne Cartier, his Canada East confederate, resigned, howling that the opposition motion was an affront to the Crown. With George Brown and his Canada East ally, Antoine-Aimé Dorion, assuming power, it looked like Ottawa’s hopes to be the capital were to be dashed. But the Brown-Dorion government fell after only four days.

J. A. Macdonald, 1858. Unknown photographer.Under the legislative rules of the day, newly appointed Cabinet ministers were obliged to resign their parliamentary seats and seek re-election before assuming their positions. Brown’s newly minted ministers duly resigned following their appointments. In a snap vote of no confidence, Macdonald and Cartier defeated the new Brown-Dorion administration shorn of its Cabinet ministers. When the Governor General refused to call a general election, Brown resigned, and Macdonald and Cartier were asked back to form a government.

J. A. Macdonald, 1858. Unknown photographer.Under the legislative rules of the day, newly appointed Cabinet ministers were obliged to resign their parliamentary seats and seek re-election before assuming their positions. Brown’s newly minted ministers duly resigned following their appointments. In a snap vote of no confidence, Macdonald and Cartier defeated the new Brown-Dorion administration shorn of its Cabinet ministers. When the Governor General refused to call a general election, Brown resigned, and Macdonald and Cartier were asked back to form a government.

Everybody thought that Macdonald and his new ministers would also resign their seats and seek re-election, leaving the new Conservative government at Brown’s mercy. But, taking advantage of another Parliamentary rule that allowed ministers to change portfolios within a 30-day period without having to seek re-election, Macdonald simply appointed the ministers in his old government to different Cabinet posts before reshuffling them back to their original positions. Macdonald, temporarily Postmaster General, ended up as Deputy Premier rather than Premier in the new government. It seems that the Governor General was worried about the optics of Macdonald regaining the premiership and insisted that Cartier become Premier, at least officially. This sneaky, or brilliant (depending on your point of view), political manoeuvre became known as “The Double Shuffle.” With Brown-Dorion out and MacDonald-Cartier back in, Ottawa’s prospects were restored.

There was one more vote to ratify Queen Victoria’s decision. Held in early 1859, the vote in favour of Ottawa squeaked through with a majority of only five votes.

Sources:

City of Ottawa, 2014. A Virtual Exhibit: Ottawa Becomes the Capital, http://ottawa.ca/en/residents/arts-culture-and-community/museums-and-heritage/virtual-exhibit-ottawa-becomes-capital-0.

Joseph Edmund Collins, 1883. Life and Times of the Right Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald, Rose Publishing Company, Toronto.

Gwyn, Richard, 2007. The Man Who Made Us: The Life and Times of Sir John A. Macdonald. vol 1: 1815-1867. Random House Canada.

Hamnett P. Hill, K.C., 1935. “The Genesis of our Capital,” Bytown Pamphlet Series #3, Ottawa Historical Society.

The Ottawa Evening Citizen 1925. “How Ottawa Was Chosen The Capital of The Dominion,” 25 June.

——————, 1930. “When Queen Victoria Made Ottawa Capital,” 22 May.

Public Works and Government Services Canada, 2013. “Parliament Hill, Pre-construction, 1826-58,” http://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/collineduparlement-parliamenthill/batir-building/hist/1826-1858-eng.html.

Image: J. A. Macdonald, 1858, unknown, File:John A Macdonald in 1858.jpg - Wikipedia

Image: Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1855, Roger Fenton, http://www.robswebstek.com/2009/04/queen-victoria-prince-albert-1855.html.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Canada's First Woman Senator

20 February 1930

At roughly 3.30 pm on Thursday, 20 February 1930, two newly-appointed senators to Canada’s Upper House of Parliament were introduced and took their seats. They were the Hon. Robert Forke of Pipestone, Manitoba, and the Hon. Cairine Mackay Wilson of Ottawa, Ontario. In and of itself, this event was not unusual, senators are routinely appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister when vacancies result from retirement or death. What made this occurrence special was that it was the first time a woman had taken a seat in Canada’s Senate. Only four months earlier, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London had ruled that women were indeed “eligible persons” to sit in Canada’s Upper House, overturning an early judgement to the contrary by Canada’s Supreme Court.

The elevation of Cairine Wilson to the Senate, announced a few days earlier on 15 February 1930, did not come as a great surprise. Her name had been mooted as a likely candidate almost immediately after the Privy Council had made its ruling. On her appointment, Prime Minister Mackenzie King said that “the government [had availed] itself of the first opportunity to meet the new conditions created by the finding of the Privy Council as to the eligibility of women for the Senate.” However, her appointment was almost stillborn as her husband was apparently opposed to her taking paid employment, and had informed the Governor General that she would decline the nomination. She quickly set the record straight and accepted the Prime Minister’s nomination over her husband’s objections.

Press reports of her appointment were positive, though they focused more on her personal attributes and family connections rather than her qualifications. Wilson was described as a tall women, still in her 40s, with a “dignified bearing.” She was “highly educated, tactful, and had unaffected manners,” with “dark hair and bright blue eyes.” The bilingual mother of eight lived at 192 Daly Avenue in Ottawa, though she and her husband were in the process of renovating and moving to the old Keefer manor house in Rockcliffe. The family also owned a summer residence in St Andrews in New Brunswick. Newspapers speculated on how she would be addressed when she entered the Senate, and on what she would wear. One newspaper article thought that she would bring to the Senate, “the feminine and hostess touch.”

Born in 1885, Wilson came from a wealthy and socially prominent Montreal family that had strong ties to the Liberal Party of Canada. Her father, Robert Mackay, a director of many leading Canadian firms including the Bank of Montreal and the Canadian Pacific Railway, had been appointed to the Senate in 1901 by his good friend Sir Wilfrid Laurier, a position he held until his death in 1916. Cairine Wilson’s husband, Norman Wilson, had been a Liberal member of parliament for Russell County in Eastern Ontario prior to their marriage in 1909. She herself was a Liberal Party activist, having chaired the first meeting of the Ottawa Women’s Liberal Club in 1922, and was Club president for the following three years. In 1928, she was a key organizer of the National Federal of Liberal Women of Canada.

Perhaps surprisingly, given her political credentials, Cairine Wilson had not been active in the suffrage movement, nor had she been involved in the legal suit, known as the “Persons Case,” that challenged the exclusion of women from the Senate. However, in her first Senate speech, given in French to honour her natal province, she saluted the “valiant work” of the five women, Emily Murphy, Henrietta Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney and Irene Parlby, commonly referred to as the “Famous Five,” who made her appointment possible. She also expressed “profound gratitude to the Government for having facilitated the admission of women to the Senate by referring to the courts the question of the right to membership.” She added that she had not sought the “great honour of representing Canadian women in the Upper House,” but desired to eliminate any misapprehension that “a woman cannot engage in public affairs without deserting the home and neglecting the duties that Motherhood imposes.”

The “Persons Case,” launched by the “Famous Five” in 1927, was a landmark decision in Canadian jurisprudence that not only opened the door for women to participate more fully in public life, but also determined how Canada’s Constitution, the British North America Act, now called the Constitution Act 1867, should be interpreted. Although women were given the vote in federal elections in 1920, with Agnes McPhail of the Progressive Party of Canada elected in the 1921 General Election in the Ontario riding of Grey Southwest, women were still barred from sitting in the Senate on the grounds that the BNA Act referred only to male senators. Successive governments did nothing to change the law despite evincing support for women’s rights.

After years of frustration, the “Famous Five” petitioned the federal government in 1927 to refer the issue to the Supreme Court for its judgement. After some discussion on the exact wording of the question, the government did so, with the Supreme Court reaching its decision on 24 April 1928. The Justices unanimously ruled against admitting women into the Senate. While they agreed there was no doubt that women were “persons,” the Justices contended that women were not “qualified persons” within the meaning of Section 24 of the BNA Act. In contrast, women could become members of the House of Commons as Parliament had the authority under Section 41 of the Act to determine membership and qualifications of Commons’ members, a latitude that did not extend to senators.

The Justices argued that under English common law women were traditionally subject to a legal incapacity to hold public office, “chiefly out of respect to women, and in a sense of decorum, and not from want of intellect, or their being for any other reason unfit to take part in the government of the country.” While the word “person” was often used as a synonym for human being, and there was legal precedent that allowed for the word to be interpreted as either a man or a woman, such an interpretation was deemed inapplicable to this case. The Justices argued that it was important to examine the use of the word in light of circumstances and constitutional law. When the BNA Act was drafted in 1867, it was clear that the drafters intended that only men would be “qualified persons” as this was the convention of the time. The section, which listed the qualifications of members of the upper house, had also been clearly modelled on earlier provincial statutes, and under those statutes women were not eligible for appointment. This restrictive interpretation of the word “person” was underscored by the use of the pronoun “he” in the relevant sections of the Act. The Justices argued that had the BNA Act’s drafters intended to allow women to become senators, something that was inconsistent with common law practices of that time, they would have explicitly included women in the definition of “qualified persons” rather than rely on an obscure interpretation of the word “person.”

The Famous Five, with the support of the Government, took the case to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, at the time the highest appellant court of Canada. On 29 October 1929, the Judicial Committee overturned the Supreme Court’s judgement ruling that women were indeed “qualified persons” to sit in Canada’s Senate. Speaking on behalf of the Committee, Lord Chancellor Viscount Sankey said that the “exclusion of woman from all public offices is a relic of days more barbarous than ours.” Standing the question on its head, he asked why the word “person” should not include women. He put forward a “living tree” interpretation of Canada‘s Constitution, viewing it as something organic “capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits.“ Consequently, the Committee interpreted the Act in “a large and liberal” fashion rather than by “a narrow and technical constraint.“ Lord Sankey’s “living tree” doctrine subsequently became, and continues to be, the basis of how Canada’s Supreme Court interprets the Constitution to this very day.

Cairine Wilson went on to have a long and distinguished career in the Senate. She was the first woman to chair a Senate Standing Committee, presiding over the Public Works and Grounds Committee from 1930 to 1947. She chaired the important Immigration and Labour Committee from 1947 to 1961, a time when Canada was welcoming hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Europe each year despite its population being less than half of what it is today. In 1957 alone, Canada welcomed more than 280,000 immigrants, of which more than 37,000 were refugees who had fled Hungary after the failed Hungarian Revolution. In 1955, she was appointed Deputy Speaker in the Senate.

As chair of the Canadian National Committee on Refugees, a position she held from 1938 to 1948, Wilson controversially went against her own government’s support for British and French efforts to appease Nazi Germany in the late 1930s. She was also an outspoken opponent of anti-Semitism, and fought (sadly with only limited success) to open Canada’s doors to Jewish refugees fleeing fascism in Europe. In 1945, she became the honorary chair of the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada founded by Lotta Hitschmanova. The USC Canada became one of Canada’s leading non-governmental organizations, providing food, educational supplies, and housing to refugees, notably children, in war-ravaged Europe during the late 1940s and 1950s. It continues to be active today in developing countries. France made Wilson a knight of the Legion of Honour for her humanitarian efforts.

Cairine Wilson died on 3 March 1962, still an active senator. A secondary school in Orleans, Ontario, now a part of Ottawa, is named in her honour.

As a postscript to this story, it took the federal government four years to nominate the second woman to the Senate. Iva Fallis was appointed in 1935 by the Conservative government of R.B. Bennett. In 2009, the “Famous Five” were posthumously made senators. As of September 2015, 32 of 83 senators were women.

Sources:

About.com. 2015. Cairine Wilson, goo.gl/EvnXVt.

Canadian Human Rights Commission, 2015. Reference to Meaning of Word “Persons” in Section 24 of British North America Act, 1867, (Judicial Committee of the Privy Council), Edwards c. A.G. of Canada [1930] A.C. 124, goo.gl/whJ2mZ.

Hughes Vivian, 2001/2002, “How the Famous Five in Canada Won Personhood for Women, London Journal Of Canadian Studies, Volume 17.

Parliament of Canada, 2015. Wilson, The Hon. Cairine Reay, goo.gl/Tk89Qs

Senate of Canada, 1930. Debates, 16th Parliament, 4th Session,Vol. 1.

The Evening Citizen, 1930. “Woman Senator Is Appointed By Gov’t of Canada,“17 February.

———————–, 1930. “Canada’s First Woman Senator Is Well Qualified By Her Talents And Training For Part She Is Called To,” 17 February.

University of Calgary, 1999. Global Perspectives on Personhood: Rights and Responsibilities: the “Persons” Case, goo.gl/xiFHvh.

Supreme Court of Canada, 2015. Judgements of the Supreme Court of Canada, Reference re meaning of the word “Persons” in sec. 24 of British North America Act, 1928-04-24, goo.gl/xF9uuc.

Image: Cairine Wilson, Shelburne Studios, Library and Archives Canada, C-0052280.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.