Ottawa Olde Forge Rug Hooking – Bytown200 Challenge

What a spectacular and creative way to help chronicle two centuries of Ottawa history!

We were thrilled when the enthusiastic members of the Ottawa Olde Forge Rug Hooking group approached the Historical Society of Ottawa in the fall of 2025, eager to join in answering the call and doing their part for the HSO 2026 Bytown200 Bicentennial Storytelling Challenge.

The history of rug-hooking, dating back to the same era as the birth of Bytown and the start of the Rideau Canal, was launched by creative crafters making use of scrap materials leftover in weaving mills in the UK and eventually here in North America.

The Bytown200-themed projects being artfully crafted by Ottawa Old Forge Rug Hooking members, will be displayed at City Hall on Heritage Day, February 17, 2026, and will be photographed and shared here on the HSO Bytown200 web page.

Below find samples of a few of their works – ranging from concept to completion.

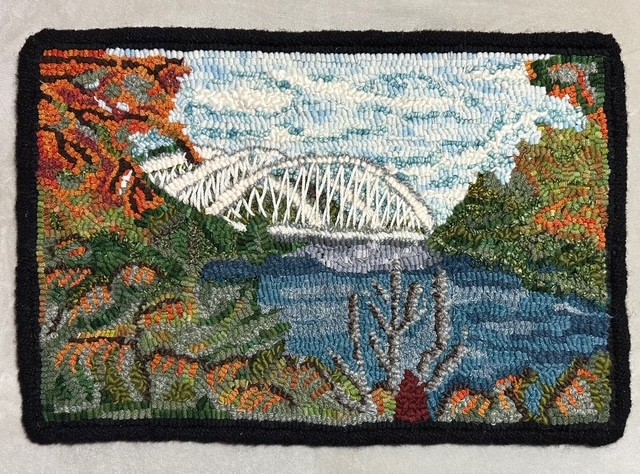

Pretoria Bridge by Lara Wellman

Pretoria Bridge by Lara Wellman

Lara Wellman : Pretoria Bridge

Aside from the Parliament Buildings, few landmarks are as iconic to Ottawa as the Rideau Canal. Built in 1915, Pretoria Bridge connects the Glebe with what was once known as Ottawa East. Now designated as a heritage structure, it stands as a cherished landmark that will continue to be enjoyed by Ottawans for generations to come.

Designed and hooked by Lara Wellman in 2024. Wellman was inspired to create this piece as a symbol representing her city.

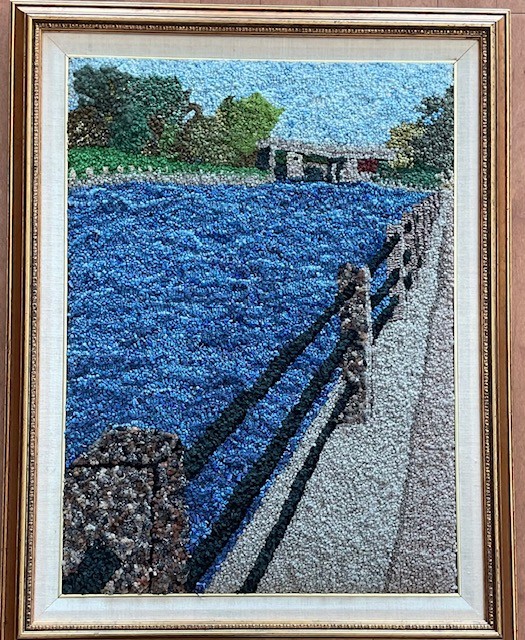

View of the Rideau Canal by Lara Wellman

View of the Rideau Canal by Lara Wellman

Lara Wellman : View of the Rideau Canal

Aside from the Parliament Buildings, few landmarks are as iconic to Ottawa as the Rideau Canal. This view of the canal is looking towards the Golden Triangle. The Bridge is for the Queensway to cross the canal.

Designed and hooked by Lara Wellman in 2023. Wellman was inspired to create this piece as a symbol representing her city.

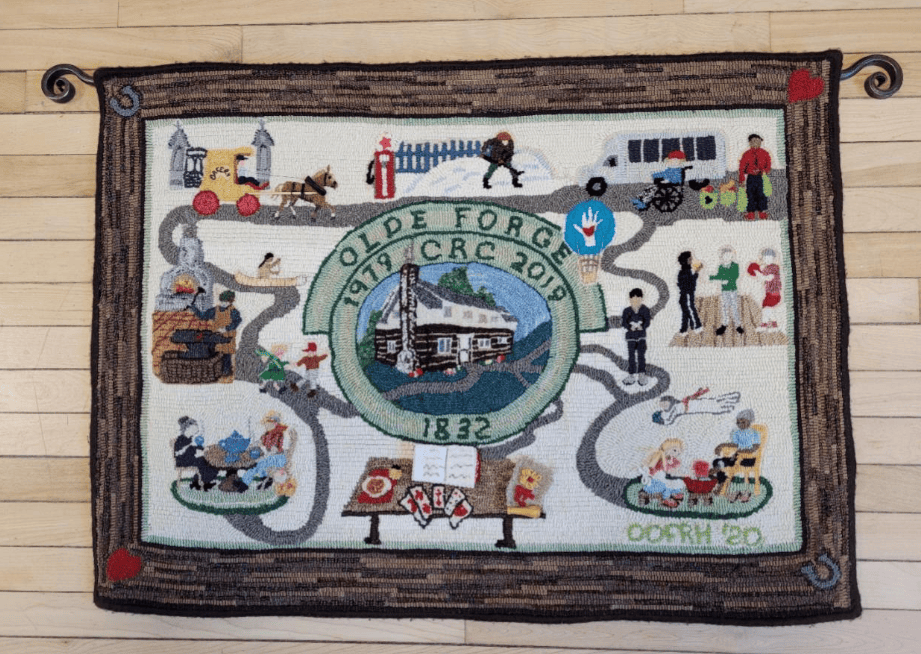

Olde Forge Community Resource Centre by members of the Ottawa Olde Forge Rug Hooking group.

Olde Forge Community Resource Centre by members of the Ottawa Olde Forge Rug Hooking group.

Olde Forge Community Resource Centre 40th Anniversary Commemorative Rug

The Olde Forge is an historic building in Ottawa’s west end, found just west of the junction of Carling Avenue and Richmond Road. Members of the Ottawa Olde Forge Rug Hooking Group made this rug to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the current residents of the Olde Forge, the Olde Forge Community Resource Centre. From its first role as a blacksmith’s shop and family home in 1832 to, decades later, a restaurant/tearoom, taxi service, gas station, tourist centre and, since 1980, a community resource centre, the building at the centre of the rug provided a wealth of inspiration for the rug’s design.

The original owner and builder of the Olde Forge, George Winthrop, is said to have arrived in Bytown from Montreal by canoe in 1832, much like Colonel By six years earlier and just as First Nations peoples had travelled since time immemorial. He built the log building and forge and ran a thriving business for many decades. The growing town of the era would have had a high demand for horseshoeing, wagon repairs, gates and many other implements made of iron. Fittingly, in 1992, it was designated a heritage property under the Ontario Heritage Act.

The rug hooking group took their name from the building where they first held regular meetings. It took an estimated 250+ hours of effort by 24 volunteers to plan and complete the rug in 2020. Nora Lee organized its design and construction, and Pat Bonn did most of the design. The story of the making of this rug was published in Rug Hooking Magazine in 2024.

Colonel By and the Memorial Cross overlooking the Rideau Canal by Nora Lee

Colonel By and the Memorial Cross overlooking the Rideau Canal by Nora Lee

Nora Lee: Colonel By and the Memorial Cross overlooking the Rideau Canal

Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers supervised the construction of the Rideau Canal. The construction was done by thousands of Irish, Scottish and French-Canadian labourers during the years 1826 to 1832. Conditions were harsh and both accidents and disease, notably malaria, killed about a 1000 workers and their families. The Rideau Canal Memorial Cross was unveiled in 2004. It can be found in Colonel By Valley, next to the canal below Major's Hill Park.

Vimy Memorial Bridge by Carol Pugsley

Vimy Memorial Bridge by Carol Pugsley

The Vimy Memorial Bridge—formerly known as the Strandherd–Armstrong Bridge—is a major modern crossing in Ottawa, completed in 2014. Spanning the Rideau River, it links Strandherd Drive in Barrhaven with Earl Armstrong Road in Riverside South, significantly improving east–west connectivity in the city’s south end. In recognition of its design and engineering excellence, the bridge received the prestigious Gustav Lindenthal Medal in 2015. Its name, proposed by two Royal Canadian Legion branches in Ottawa, commemorates the Battle of Vimy Ridge and reflects the city’s tradition of honoring Canada’s military history through its public landmarks.

Tawadina Lookout, Gatineau Park by Marion Agnew

Tawadina Lookout, Gatineau Park by Marion Agnew

Tawadina Lookout is a scenic viewpoint in Gatineau Park, Québec, perched along the Eardley Escarpment and reached by hiking trails such as the Wolf Trail. The lookout offers sweeping views over the Gatineau Hills and the Ottawa River Valley, making it a popular destination for hikers seeking both natural beauty and elevation. Surrounded by forest and exposed rock, Tawadina Lookout exemplifies the rugged landscape of the park and rewards a steady climb with one of its more expansive inland vistas.

Huron cabin in winter, Gatineau Park by Marion Agnew

Huron cabin in winter, Gatineau Park by Marion Agnew

Huron Cabin: The Huron-Wendat played an important role in the early history of the Bytown area long before its founding in 1826. For centuries, they used the Ottawa River and its tributaries as major travel and trade routes, establishing camps and portages that later guided European movement through the region. Their knowledge of the land, waterways, and seasonal cycles shaped early exploration and settlement patterns and influenced relations between Indigenous peoples and newcomers. When Bytown emerged during the construction of the Rideau Canal, it did so on Indigenous land long known, used, and understood by the Huron-Wendat and other Algonquin-speaking peoples, whose presence formed an essential part of the area’s deeper historical foundation.

Notre-Dame Cathedral, Sussex Drive by Andre PInard

Notre-Dame Cathedral, Sussex Drive by Andre PInard

Notre-Dame Cathedral, Sussex Drive

Adapted logo with permission

Hooked by André Pinard

7 x 11 inches

Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica of Ottawa is one of the city’s oldest and most important religious landmarks. Founded in 1841 as a small wooden church serving the Catholic community of Bytown, it evolved as the settlement grew during the construction of the Rideau Canal. The present stone cathedral, begun in 1846 under Bishop Joseph-Eugène-Bruno Guigues, was built in the Gothic Revival style using local stone and later enhanced by its distinctive twin tin spires. Its richly decorated interior reflects the artistic and cultural influence of French and Irish Catholic communities. Designated a minor basilica in 1879 by Pope Leo XIII, Notre-Dame remains a key symbol linking Ottawa’s early history to the modern capital.

The basilica holds deep family significance for André, as generations of his family were married, baptized, and received their first communion there. Parish registers show that Émélia Pinard, born in Bytown on June 25, 1829, daughter of Louis Pinard and Catherine Alexandre, was baptized the same day. Although no church building yet existed and the parish had not been formally established, missionary clergy were already keeping records, marking the Pinard family’s early connection to Notre-Dame.

Girls on the Beach by Julie de Loë

Girls on the Beach by Julie de Loë

Hog's Back Falls: Girls on the Beach

Rug hooked by Julie de Loë – Completed January 2026

Materials used: burlap backing, wool cloth and 100% wool

Description: Pictured are Claire Johnson, Mary Maingot and Frances Clark swimming at Hog’s Back Park/Mooney’s Bay, April 30, 1954. To the far left, the white building and boat house where Paul’s Boat Lines found its beginnings.

City of Ottawa Archives MG393-NP-31052-001 CA004093

City of Ottawa Archives MG393-NP-31052-001 CA004093

Photo used with permission

Green Shoal Lighthouse by Julie de Loë

Green Shoal Lighthouse by Julie de Loë

Green Shoal Lighthouse

Rug hooked by Julie de Loë – Completed: January 2026

Materials used: Burlap Backing, wool cloth and 100% wool

Inspired by: Original photograph by Lou Bouchard Copyright 1964; Article and Drawing by Andrew King, Ottawa Rewind 2015/03/05.

Green Shoal is located in the middle of Ottawa River, about twelve kilometres downstream from Ottawa. It sits just north or the gap between Upper Duck Island and Lower Duck Island. Green Shoal Lighthouse was active into the early 1970s. The Green Shoal Lighthouse inspired the naming of the Beacon Hill neigbourhood as it was visible from the North part of this community.

Originally built in 1860, it received a new pier in 1900 and an updated light. It’s base is 20 feet in diameter and it rose to 23 feet above summer level of the river. The wooden tower stood 21 feet high and had a fixed white light. The light was 38 feet above the summer level of the river.

Today, only the steel-clad foundation remains standing in Ottawa River.

Keepers: George Barthgate (1860 – 1861), David Thomas (1861 – 1865), Mrs. D. Thomas (1865), Alfred Laberge (1866 – 1902), Albert Laberge (1902 – 1920), D. Mitchell (1920 – at least 1923).”

References: Annual Report of the Department of Marine, various years.

Log Driver's Waltz by Jule de Loë

Log Driver's Waltz by Jule de Loë

Log Driver’s Waltz

Rug hooked by: Julie de Loë - Completed: Jnuary 2026

Materials used: burlap backing, wool cloth and 100% wool

Description: The Log Driver’s Waltz is a known Canadian folk song, written by Wade Hemsworth. The song was recorded by many artists Kate & Anna McGarrigle, Mountain City Four, Captain Tractor and The Hidden Cameras to name a few. The lyrics were translated in French by Philippe Tatartcheff.

In 1979 the National Film Board released this animated film as part of its Canada Vignette series. One of the most-requested in the collection of the National Film Board of Canada, it celebrates log drivers and the lumber industry.

This rug was inspired by the film and used with kind permission from the National Film Board of Canada.

Man with Two Hats by Christine Tibelius

Man with Two Hats Designed and hooked by Christine Tibelius 2026

The statue is at Dow’s Lake in Ottawa in Commissioners Park, which is beside the lake. The statue is officially called The Man With Two Hats. It’s a bronze public sculpture about 4.6 m tall, showing a stylized human figure holding a hat in each hand. It was created by Dutch artist Henk Visch. The statue in Ottawa was unveiled on May 11, 2002 by Princess Margriet of the Netherlands.

The statue commemorates the role Canadian soldiers played in freeing the Netherlands from German occupation during the Second World War. Canada’s involvement meant a lot to the Dutch people, and as a sign of gratitude the Netherlands gifted this sculpture to Canada. There’s an identical statue in Apeldoorn, Netherlands (at the National Canadian Liberation Monument), and the two are symbolic “twins,” connecting the two countries across continents. The outstretched arms holding two hats can represent joy and celebration of freedom, the strong friendship between Canada and the Netherlands, and the shared history of liberation at the end of World War II.

Princess Margriet was actually born at the Ottawa Civic Hospital during the war — her mother stayed in Canada because the Dutch royal family was in exile — and that personal connection adds meaning to why the monument is in Ottawa.

Joanne Dickert’s project depicting John Ceprano’s rock sculptures along the Ottawa River.

Joanne Dickert’s project depicting John Ceprano’s rock sculptures along the Ottawa River.

Parliament Hill Peace Tower by Elaine Armstrong.

Parliament Hill Peace Tower by Elaine Armstrong.

Visit the OOFRH website to learn more about their organization: ottawarughooking.com

James Powell – Today in Ottawa's History

James Powell takes us back to the early days of the Rideau Canal and Bytown with stories about the Shiners’ War, the Stony Monday Riot, The ByWard Market, Bytown’s first newspaper, Bytown's journey to becoming Canada's capital... and more.

James is the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History giving a day-by-day account of local history.

The Chaudiere Bridges

One of the most pressing priorities for Lt. Colonel By and his engineering colleagues, was to span a bridge across the Ottawa River in order to transport essential supplies and workers from Wright’s Town urgently needed to begin construction of the Rideau Canal: The Chaudière Bridges, 28 September 1826

The Canal

James shares the story of one of the most remarkable engineering feats of its era – the construction of the Rideau Canal: The Canal, 29 May 1832

The Shiners’ War

For the better part of a decade, lawlessness reigned as Bytown’s citizens were terrorized by violent gangs of thugs known as the “Shiners”, cunningly manipulated by the ruthless and ambitious Peter Aylen, a man willing to fuel religious and linguistic division in his attempt to solidify his own unassailable Ottawa Valley timber empire: The Shiners’ War, 20 October 1835

Ottawa’s First Newspaper

500 copies of Bytown’s first newspaper hit the streets on February 24, 1836. James Powell flips through the pages of that first four-page edition and takes a peek at what its first subscribers would have been reading: Ottawa’s First Newspaper, 24 February 1836

The ByWard Market

James Powell traces the history of Lowertown’s almost two-century old ByWard Market: The Byward Market, 4 November 1838

Corporation of Bytown

John Scott was elected the first mayor of Bytown – twice. Initially incorporated in 1847, with John Scott elected as Bytown’s first mayor, Bytown’s charter was subsequently disallowed following a dispute with the Ordnance Department, the military administration that had become accustomed to being in charge since the days of Lt. Colonel John By. James Powell shares the story of how matters were eventually resolved and how, upon reinstatement of Bytown’s charter, John Scott was, for a second time, elected as Bytown’s first mayor: The Corporation of Bytown, 28 April 1847

Stony Monday Riot

In 1849, the Stony Monday Riot erupted in Lowertown between the Reformists and the Tories. Dozens of injuries and one death resulted when as the (mostly Protestant) Tories, furious over the impending visit of the Governor General, Lord Elgin, clashed with the (largely working-class Catholic) Reformists: Stony Monday Riot, 17 September 1849

Lord Elgin Visits Bytown:

Remarkably, Lord Elgin’s visit in 1853 -- only four years after the Governor General had been forced to cancel his visit following Bytown’s violent Stony Monday Riot -- resulted in Lord Elgin’s recommendation that Bytown to be chosen as the Province of Canada’s new capital: Lord Elgin Visits Bytown, 27 July 1853

Choosing Canada's Capital

Toronto, Kingston, Hamilton, Montreal and Quebec City were among Bytown’s rivals in the intensely-fought contest be chosen as the Province of Canada’s new capital. Bytown even went so far as to change its name to “Ottawa” in hopes of distancing itself from its (well-earned) reputation as a violent and uncivilized backwoods lumber town. James Powell retraces Bytown’s surprising journey to becoming Queen Victoria’s unexpected choice as Canada’s new capital: Queen Victoria Chooses Ottawa, 31 December 1857

Ottawa’s Centenary

In celebration of Bytown’s 100th anniversary in 1926, the Ottawa Journal published an article predicting what Ottawa might be like a century later, in 2026. Today, as we mark the 200th anniversary of the founding of Bytown, James Powell takes us back to 1926 for a look at those predictions and at how else our city celebrated our centenary: Ottawa’s Centenary, 16 August 1926

Lynn Gehl – Akikodjiwan

Lynn Gehl, PhD, author, activist and member of the Algonquins of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation, makes the case, in this 2018 article, that historic and current development has betrayed the "Asinabka" vision of the late Chief William Commanda and desecrates what should alternatively be preserved and honoured as our nation's potential "heart of reconciliation":

The Chaudière Falls (Akikodjiwan) and surrounding landscape have long been a sacred place for Algonquin and other First Nations. How has this been impacted over the past two centuries, since the arrival of Europeans in the Ottawa area?

Has the historic and ongoing development of the Chaudière district (Chaudière Falls and Chaudiére, Albert, and Victoria Islands) been emblematic of our nation's disregard for Indigenous rights and jurisdiction?

Akikodjiwan - The Destruction of Canada’s Heart of Reconciliation

Prior to colonization, the Algonquin Anishinaabeg relied on the land and waterways now known as the provinces of Ontario and Quebec and the Ottawa River. Through the gifts they provided, the Algonquin achieved mino-pimadiziwin (the good life).

It was through Nanaboozo’s hardship of living without a father, his process of seeking revenge and learning forgiveness, that human beings understand reconciliation. The Spirit of the West Wind gave the First Sacred Pipe to his son Nanaboozo, instructing him about the rituals of reconciliation that include ceremony and prayer as the practices of reunion between father and son, peoples, and nations.

“During the historic treaty process British officials ignored the Algonquin because our very territory was becoming the heart of Canada.”

While many people think this Nanaboozo story is a romantic belief that lacks rationality, it is much more. Sacred beliefs that value the natural world are far more sustainable and intelligent than the destruction that manifests through the current economic paradigm, resulting in the polluting of our land and waterways with such things as plastic, sewage, chemicals, and radioactive particles.

During the historic treaty process British officials ignored the Algonquin because our very territory was becoming the heart of Canada. Through subjugating the Algonquin, the colonizers were able to appropriate Algonquin territory and centralize their Parliament base.

Many people today think Canada is in a better place with Indigenous nations. This is not so. Through the power gained from pilfering Indigenous land and water rights, Canada continues to divide the Algonquin through practices such as obfuscating and spinning what Canada’s treaty responsibilities are.

“In a world of economic power that lacks an understanding of the importance of preserving what is sacred, Algonquin jurisdiction and human rights continue to be pushed aside.”

Akikodjiwan and Akikpautik (Pipe Bowl Falls), located in the Ottawa River just upstream from Canada’s Parliament, are the very land and waterscapes where Creator placed the First Sacred Pipe. Through colonization Akikpautik was eventually dammed, and the islands that make up the larger Akikodjiwan landscape are now called Chaudière, Albert, and Victoria Islands. It was Grandfather William Commanda’s vision to have this sacred place restored. His Asinabka plan was endorsed and promised by many.

Unfortunately, despite Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s rhetoric of respecting a “nation-to-nation” relationship and calling for “reconciliation,” the current Liberal government is permitting the further desecration of this sacred place. I offer here a timeline of the continued destruction of the ultimate place of reconciliation inscribed by Creator.

1613: Samuel de Champlain records the Anishinaabeg offering tobacco to Akikpautik (Pipe Bowl Falls), also called Asticou meaning “the boiler.” Champlain translates this as “Chaudière.”

1806: Philemon Wright’s lumber industry begins within Algonquin traditional territory in the Ottawa River Valley.

1854: The Government of the Province of Canada approves an Order-in-Council reserving the Chaudière Islands and adjacent area of the Ontario shoreline for public purposes.

1856: Leases are issued so the lumber industry can harness the water’s energy for their sawmills. These lots are on Chaudière, Albert, and Victoria Islands.

1880: J.R. Booth now holds most of the lease interests on the Islands.

1908: A large ring dam is constructed extending from Chaudière Island over the entire span of the falls. Eventually E.B. Eddy takes over its operation for pulp and paper manufacturing purposes.

1913: William Commanda is born and becomes a respected knowledge holder and Grandfather. Eventually he has a vision about re-naturalizing Chaudière Falls and the Islands. He wants the sacredness of Akikpautik returned to its natural form and the islands housed with a park, an Indigenous centre, and a peace-building meeting site for all peoples. He calls his plan “Asinabka.”

1936: Prime Minister Mackenzie King commissions Jacques Gréber to create a master plan that will govern the development of the National Capital Region.6 It was completed in 1950. Gréber concludes the most effective improvement will be the central park at the Chaudière Falls.

1958: The National Capital Commission (NCC) is established to implement Gréber’s Master Plan.

1969: The NCC purchases 40 per cent of E.B. Eddy’s operations. As a condition the NCC gains first call on E.B. Eddy’s remaining property.

1990: Plans are announced regarding an Indigenous Centre on Victoria Island.

1998: Grandfather Commanda consults with the NCC, Douglas Cardinal, Algonquin communities in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, and Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples regarding his Asinabka Plan.

Domtar purchases E.B. Eddy’s operations. This does not mean Domtar purchased the land and waterscape.

2003: Grandfather Commanda asks the NCC and Domtar to produce the deeds to the Islands; nothing materializes.

2004: The Ministry of Canadian Heritage grants Grandfather Commanda $50,000 to further conceptualize his Asinabka Plan.

2006: The NCC endorses Asinabka and allocates $35 million toward it.

Grandfather Commanda prophesizes, “It is a vision for the revitalization of this Sacred Site, Asinabka, at the circular Chaudière Rapids, Akikpautik: The Pipe Bowl Falls.”

Stephen Harper is elected as prime minister and opens the doors for corporate development in respect to the Islands.

2007: Domtar closes their paper mill operation.

2010: The City of Ottawa endorses Grandfather Commanda’s Asinabka Plan.

2011: With great sadness, Grandfather Commanda passes into the spirit world.

2012: Domtar places their interests up for sale. The NCC applies for funds but the treasury board refuses.

Canada permits the transfer of the Ring Dam to Energy Ottawa, a municipally owned power company.

2013: Windmill Development Group publicly announces interest in the Islands, discussing the need for re-zoning for their condominium and commercial development project.

2014: The Circle of All Nations reports that the Service Ontario Land Registry indicates Chaudière Island is not owned by Domtar.

Ottawa City council votes in favour of Windmill’s application to re-zone the islands from “parks and open space” to “downtown mixed use.”

Kitigan Zibi First Nation releases a statement: “Our traditional territory has always been and continues to be, Unceded. We hereby put Canada, Québec and Ontario on notice that [the] status quo, in which our Aboriginal title lands are taken up by governments and industry, is not acceptable.”

Douglas Cardinal, Romola V. Thumbadoo-Trebilcock, Richard Jackman, Larry McDermott, and Lindsay Lambert file an appeal to the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) regarding the re-zoning.

2015: Windmill re-names their project as “Zibi.”21 Chief Gilbert Whiteduck argues the use of the Algonquin word is cultural appropriation.

May 2015: The City of Ottawa files a motion requesting the OMB dismiss the five appeals regarding the re-zoning due to a lack of planning grounds. This would result in the denial of a full hearing.

June 2015: The OMB pre-hearing begins with member Richard Makuch presiding.

August 2015: The Ottawa Citizen reports that Domtar sells their operations to Windmill. This involves land that Domtar has never proven they own.23 The Service Ontario Land Registry identifies Windmill as leasing the land from Domtar.

The OMB pre-hearing resumes. The appellants argue consultation is required, and that the re-zoning was a departure from the Gréber and Asinabka Plans.

The City and Windmill argue the appellants lack planning grounds, Chaudière Island is no longer an Indigenous cultural site of significance because of the industrial era, and all the land is in private hands. Wolf Lake, Timiskaming, Eagle Village, and Barriere Lake First Nations call for the protection of Akikodjiwan.

November 2015: Makuch dismisses the five appeals on the grounds that the re-zoning conforms to the City’s plan, the appellants failed to raise legitimate planning grounds. He also argues there was adequate consultation with Pikwàkanagàn First Nation and the organization known as the Algonquins of Ontario. In this way he imposes colonial provincial borders on the process of justice thus denying the rights of the larger Algonquin Nation that spans the Ottawa River and includes the Algonquin located in Quebec, both status and non-status Algonquin.

Justin Trudeau is sworn in as prime minister claiming to respect the “nation-to-nation relationship” and genuine “reconciliation.”

The Assembly of the First Nations of Québec and Labrador pass a resolution to protect Akikodjiwan.

Despite Algonquin and settler opposition, Energy Ottawa begins drilling a water channel deep into the bedrock of Chaudière Island27 for additional hydroelectric generation.

March 2016: The appellants appear in the Ontario Divisional Court (ODC) seeking leave to appeal the OMB decision. Justice Charles T. Hackland dismisses them on the grounds the OMB made no errors of law.

June 2016: In protest, more than five hundred people, both settler and Indigenous, walk from Victoria Island to Parliament Hill.

October 2016: Appellants appeal again to the ODC regarding Hackland’s dismissal. A panel of three judges denies the appellants.

December 2017: Although it is said the Tsilhoqot’in decision ushered in a new paradigm regarding Indigenous rights of consent versus consultations, on December 15, 2017, the Government of Canada approved a series of land transfers between the National Capital Commission, Public Services and Procurement Canada, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, and Windmill Dream Zibi for lands on islands in the Ottawa River. This happened without the consent of the larger Algonquin Nation, which includes the status and the non-status in both Quebec and Ontario.

February 2018: As of February 5th, 2018 the Service Ontario Land Registry assigns Windmill Dream Zibi Ontario Inc. parcels of land on Chaudière Island and Albert Island.

Contrary to what the City of Ottawa, Windmill Development, and the Ontario Municipal Board argued, the appellants rested their arguments on legitimate planning grounds: Jacques Gréber’s Master Plan and Grandfather William Commanda’s Asinabka Plan.

Both plans long pre-dated Windmill’s project, yet in a world of economic power that lacks an understanding of the importance of preserving what is sacred, Algonquin jurisdiction and human rights continue to be pushed aside. Clearly the Liberal government’s rhetoric of respecting a nation-to-nation relationship and seeking genuine reconciliation is a bold-faced lie.

Author Lynn Gehl © 2018, Lynn Gehl Ph.D. All rights reserved.

(Published in the Watershed Sentinel)

Reprinted with permission of the author.

Lynn Gehl, PhD., is a member of Pikwàkanagàn First Nation. She is the author of two books: 2014’s The Truth That Wampum Tells: My Debwewin on the Algonquin Land Claims Process with Fernwood Publishing; and 2017’s Claiming Anishinaabe: Decolonizing the Human Spirit with the University of Regina Press.

Here is a link to the full article: https://watershedsentinel.ca/articles/akikodjiwan/

Follow this link to view more of Lynn Gehl's work: www.lynngehl.com

Listen to the February 2026 HSO presentation with Lynn Gehl: Algonquin Anishinaabeg of the Ottawa River Valley: Yesterday Today Tomorrow

Dr. Gehl recommends these resources as further reading:

Matchewan, J-M. (1992, February 4). Algonquin Nation as Represented by Barriere Lake, Kipawa, Timiskaming and Wolf Lake. Retreived from https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/aanc-inac/R5-648-1992-eng.pdf

Di Gangi, P. (2018, April 30). Algonquin Territory: Indigenous title to land in the Ottawa Valley is an issue that is yet to be resolved. Canada’s History. Retrieved from https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/politics-law/algonquin-territory

Dumont, A. (South Wind). (2013, December 28). The Kettle of Boiling Waters: Chaudière Falls, Algonquin Territory. Albert Dumont.Retrieved from http://albertdumont.com/the-kettle-of-boiling-waters-chaudiere-falls-algonquin-territory/

Gehl, L. (2016, November 15). Deeply flawed process around Algonquin land claim agreement. Policy Options.Retrieved from https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/november-2016/deeply-flawed-process-around-algonquin-land-claim-agreement/

Gehl, L. (2018b, March 8). Akikodjiwan: The Destruction of Canada’s Heart of Reconciliation. Watershed Sentinel. Retrieved from https://watershedsentinel.ca/articles/akikodjiwan/

Huitema, M.E. (2000). “Land of Which the Savages Stood in no Particular Need”: Dispossessing the Algonquins of South-Eastern Ontario of Their Lands, 1760-1930 . Master of Arts thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON. Retrieved from https://iportal.usask.ca/record/6234

Jury, E.M. (1966). Tessouat (Besouat); Tessouat (Le Borgne de l’Île); Tessouat (Tesswehas, Le Borgne de l’Île) Paul. Dictionary of Canadian Biography (Vol. 1) (pp. 638-641). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Here they are online.

- https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tessouat_1603_13_1E.html

- https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tessouat_1636_1E.html

- https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/tessouat_1654_1E.html

Matchewan, N. (2008). Blockades: Algonquins of Barriere Lake Defend the Forest, 1989-2008. In First Nations Strategic Bulletin. Volume 6, Issue 1, September – October 2008. (pp. 28-29). Retrieved from https://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/300/first_nations_strategic_bulletin/2008/v06n02.pdf

Pasternak, S. (2009, October 26). They’re Clear Cutting Our Way of Life: Algonquins Defend the Forest. Upping the Anti. Retrieved from https://uppingtheanti.org/journal/article/08-theyre-clear-cutting-our-way-of-life/

Pugliese, K. (2005). ‘So, where are you from?’ Glimpsing the history of Ottawa-Gatineau’s Urban Indian Communities. Master’s thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON. Retrieved from https://repository.library.carleton.ca/concern/etds/0v838113m

Sarazin, G (1992). 220 Years of Broken Promises. In B. Richardson (Ed.), Drumbeat: anger and renewal in Indian country (pp. 167-200). Toronto: Summerhill Press. (original work published 1989)

Whiteduck, K. (2009). Our Majestic Forests: An Aboriginal View of Algonquin Park. In D. Euler & M. Wilton (Eds.), Algonquin Park: The Human Impact (pp. 36-54). Espanola, ON: OJ Graphix Inc.

http://www.asinabka.com/geninfo.htm

https://qshare.queensu.ca/Users01/gordond/planningcanadascapital/greber1950/

https://ricochet.media/en/101/ottawa-city-council-approves-rezoning-sacred-algonquin-site

http://rabble.ca/news/2016/06/condominium-development-threatens-protection-algonquin-sacred-site

Jean-Luc Pilon – Paddling through the Past

What vast history existed here in the Ottawa area, long before the establishment of Bytown and the Rideau Canal? Renowned archaeologist/anthropologist Dr. Jean-Luc Pilon helps us reveal our area’s past.

In this episode of the HSO/Rogers TV series, "Time Travelling with the Historical Society of Ottawa", Dr. Jean-Luc Pilon shares "An Archaeologist's Perspective: Uncovering the Ottawa Area's Ancient Past": https://www.historicalsocietyottawa.ca/resources/videos/time-travelling-with-jean-luc-pilon-an-archaeologist-s-perspective-uncovering-the-ottawa-area-s-ancient-past

In this fascinating 45-minute video, “Paddling through the Past”, Dr. Pilon leads us on an inspiring exploration of the clues that are all around us: https://youtu.be/uBUP6OXNd08?si=LT990dWPkTdcEakd

Dave Allson: Ottawa’s Shoreline - Built from Garbage

Dave Allston is a ‘trash talker’. Specifically, on the afternoon of Saturday, January 27, 2024, he talked to the Historical Society of Ottawa at our first in-person presentation of 2024 on how the Ottawa River shoreline was reshaped during the early 1960s using garbage. Dave is the senior asset manager (heritage) at National Defence and also an author, columnist, researcher, and runs the blog, The Kitchissippi Museum. He was making his 3 rd presentation to the Society. The session, which was hosted by the Main Branch of the Ottawa Public Library, received a record turnout of 113 attendees, who were captivated by Dave’s account.

Dave explained to us that in 1959 the City of Ottawa was facing a major problem. The two municipal dumps, one on Riverside Drive and the other on Raven Road, were both reaching capacity and would need to be closed within two years. A solution was urgently needed. Likely inspired by Toronto’s redevelopment of their waterfront and similar work in other cities, in February 1959 the Ottawa Works Commissioner, Frank Ayers, recommended to the Board of Control that Nepean Bay, which lay just to the west of the current site of the Canadian War Museum, could be used as their new landfill site. The Board directed him to approach the National Capital Commission with the idea. Their response was immediate and enthusiastic. The NCC had envisaged creating a giant beach along the Ottawa River along with a large playground and other recreation facilities, but had no clear plan for how to proceed. The City’s proposal was approved in one week. The scheme, part of the NCC’s implementation of the Greber Plan, would eventually also encompass Lazy Bay just north of Laroche Park and Bayview Bay between the Lemieux Island Bridge and the Chief William Commanda Bridge.

The plan was simple. Build a causeway across the mouth of the bay that would both seal it off from the river and provide a roadway for the garbage trucks to dump their loads. They would then pump out the water from behind the causeway; the bay was only 4 or 5 feet deep. Ignore the many feet of water-rotted sawdust that covered the bottom of the bay, a by-product from the lumber industry. Then fill the whole thing with garbage, finally to be covered by rock and a thick layer of soil. Presto, 50 acres of new land created and a temporary end to the garbage crisis. Work commenced on the causeway in the early months of 1962 and the dump was opened during the week of March 4, 1963.

There would be a massive amount of rock required to build the causeway, which would extend west to Lazy Bay. Dave explained that fortunately, there were other major projects underway in Ottawa at that time, which both provided the necessary rock for the causeway and a convenient disposal solution for the other projects. Tunnelling for the Ottawa Interceptor and Outfall Sewer project would create millions of tons of rock. The tunnels ran from Booth Street under Wellington past the Chateau Laurier and east through to the new sewage disposal plant at Green’s Creek. At this time, Ottawa pumped all its raw sewage directly into the Ottawa River. The new treatment plant would partially treat this sewage, the City feeling that it was not worth the additional expense to fully treat the sewage as the communities upstream continued to pump their sewage into the river untreated. A second excavation project to entrench what is now the OC Transpo’s Trillium Line and take it underneath Dow’s Lake, also provided rock for the causeway. Finally, the major excavation project involved in the construction of the National Arts Centre would provide the fill needed to cover all the garbage once the dump was full.

With the closure of the Riverside Drive landfill on March 9, 1963, all city garbage was sent to the new site, which was expected to have a lifespan of two years. The city even placed ads in the newspaper to encourage their citizens to bring their own garbage to the new dump. Dave revealed that there were other factors at play that would dramatically shorten the life of the new landfill. The National Capital Commission had begun an urban renewal project in LeBreton Flats in 1962 and as residents of the area moved away, their former homes and businesses remained empty. It didn’t take long until this proved to be a problem, encouraging squatters, cases of arson and a range of other undesirable activities. As such, the NCC began demolishing the structures as soon as they became vacant, and as the new city dump in Nepean Bay was handy, the remains were carted there. The result was that the dump filled quickly and was closed on February 1, 1964, less than a year after it opened.

By this time the NCC had abandoned their grandiose beach plans in favour of simple parkland, other uses, and a parkway, now known as the Kichi Zībī Mīkan. This meant excavation of thousands of tons of the recently buried garbage and transferring it west to either Bayview Bay or Lazy Bay. Although the parkway provided a scenic drive and a much needed west – east link, it also separated the communities from the river and areas that had traditionally formed part of their neighborhood.

Dave reminded us that this all happened over the span of a few years some 60 years ago and that today few are even aware that this took place. This is true even for some members of the National Capital Commission. As new development is proposed and eventually undertaken in these areas, such as the construction of a number of embassies on Lazy Bay Commons, do the planners know what to expect? Will the solution to our garbage crisis of 1959 come back to haunt us in the years ahead, and, as we face the same problem again, what lessons are to be learned from our response back then?

Earlier on the morning of January 27, 2024, CBO-FM featured an interview between Dave and the host of their program “In Town and Out”, Giacomo Panico. The interview carries additional information on the topic and can be heard at: Ottawa River shoreline made out of garbage | In Town and Out with Giacomo Panico | Live Radio | CBC Listen.

Uncovering Our Region’s Ancient Past

The Historical Society of Ottawa was honoured to welcome back Dr. Jean-Luc Pilon as the featured speaker at the April 12, 2023, speaker series session, hosted by the Main Branch of the Ottawa Public Library. Dr. Pilon is a renowned archeologist, long-time curator of Central Canada archaeology at the Canadian Museum of History, an educator, and was the first recipient of the J.V. Wright Lifetime Achievement Award from the Ontario Archaeological Society.

Dr. Pilon, who had spoken to us in November 2016, led us through some of the history of archeological activities in the Ottawa area along with the views of some individuals, organizations and governments. He pointed out that Europeans immediately grasped the importance of this location, Champlain making note of it in his journal in 1613. A Royal Proclamation of 1763 offered a degree of protection to Indigenous lands west of the Appalachian Mountains, but land grants from the Crown and later questionable Crown treaties and purchases, such as the Rideau Purchase of 1819, served to strip the Indigenous peoples of their land and heritage. Philemon Wright noted the objection of the local Indigenous population as he expanded his own enterprises in the area in the early 1800s, especially logging in support of the Napoleonic Wars. Later, about 1843, Dr. Edward van Courtland, a local medical doctor, naturalist and archeologist, identified a major ceremonial and burial site in the area, collecting many artifacts from his find. Archeology, at that time, had little concept of context and would from today’s perspective be more closely associated with looting than science. In describing the site, Dr. Courtland failed to mention on which side of the Ottawa River it fell, leading to a misunderstanding about the location of his discovery that was to endure and propagate for over 170 years. Writing for the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1901, Gertrude Kenny provided an anecdotal account of the Indigenous culture that had existed in the area for hundreds of years, but provided no sources for her account. Dr. Pilon noted many others who found artifacts or provided their own interpretations.

Dr. Pilon described how the artifacts flowed to and through a series of museums including the Bytown Mechanics Institute, the Literary and Scientific Society of Ottawa, the Geological Survey of Canada, and now the Canadian Museum of History. The artifacts that have been collected in the valleys of the Ottawa and Rideau rivers have a story to tell. Implements of stone quarried from deposits in Labrador, the Hudson Bay / James Bay and New York State areas, copper from west of Lake Superior, pottery of the Middle Woodland period, virtually identical to that found in the Lake of the Woods area, speak to a broad-based and sophisticated trading network with a critical hub in the Ottawa / Gatineau area that had been active for more than 4,500 years before the arrival of European settlers. The meeting of the Gatineau, Rideau, and Ottawa rivers made this an ideal location for the exchange of goods and ideas, while the presence of the Chaudière Falls, also known as Akikodjiwan, made this a significant spiritual location as well.

During excavations associated with the renovation of the Centre Block of the Parliament Buildings, a stone knife, dated between 2,500 and 4,000 years old was discovered. The knife has been returned to the stewardship of the Algonquin Anishinabe peoples and it is expected that it will be displayed in the Center Block when it reopens.

Dr. Pilon reminded us that as we think about our city, we must remember that this was a center of commerce and culture for thousands of years before anything we see today.

Following Dr. Pilon’s presentation, we were privileged to be joined by several students from Anishinàbe Odjìbikan. Anishinàbe Odjìbikan is an Indigenous Archaeological Field School that provides First Nations students from Pikwakanagan and Kitigan Zibi the phenomenal opportunity to take part in archaeological digs along the shorelines and uncover and better understand their own ancestral past. Jenna and Kyle gave us some background to their program,. Planned in 2019, it, like most things, was delayed by Covid. In 2021, 8 students, 4 from each community participated, while in 2022, 16 students, 10 from Kitigan Zibi and 6 from Pikwakanagan took part. Their hope is to continue the program for at least another three years. The program has strong support from the communities, financial support from the federal government and archeological mentoring from the National Capital Commission. It is hoped that some financial independence can be achieved through access to bid on government contracts.

Jenna and Kyle explained some of the differences between their approach and that of traditional archeology, which has largely ignored First Nation’s voices and their traditional knowledge. They explained that while recovering their own people’s artifacts, they adopt appropriate cultural practices, such as ceremonies to thank the land for its care of the items before and after their recovery and the renewed use of the recovered items as they had been originally intended. In recovering the artifacts, the students and their communities recognize that they are also recovering their own heritage, allowing them their own interpretation not one from a colonial perspective. These artifacts also provide an undeniable proof of the occupation of this land by indigenous peoples for thousands of years before the arrival of the first colonists.

Jenna and Kyle expressed the urgency of their undertaking. Climate change, high water levels and urbanization are damaging and destroying potential sites. They see this program as critical in providing the skills and trained individuals needed to perform the work ahead.

Following their presentation, the students displayed a number of the artifacts they had uncovered and responded to many questions posed by audience members who came down to the stage for a closer look and a chat.

This in-person session, the most popular this season with over 90 people attending, left all of us with a thirst to learn more about the earlier history of the land on which we live and the peoples to whom it belongs.

Artifacts presented by Anishinàbe Odjìbikan.

Artifacts presented by Anishinàbe Odjìbikan.

Dr. Jean-Luc Pilon has shared this excellent video, a guided tour as he explores the heart of our region: Paddling through the past - Ottawa-Gatineau's Ancient Cultural Landscape.

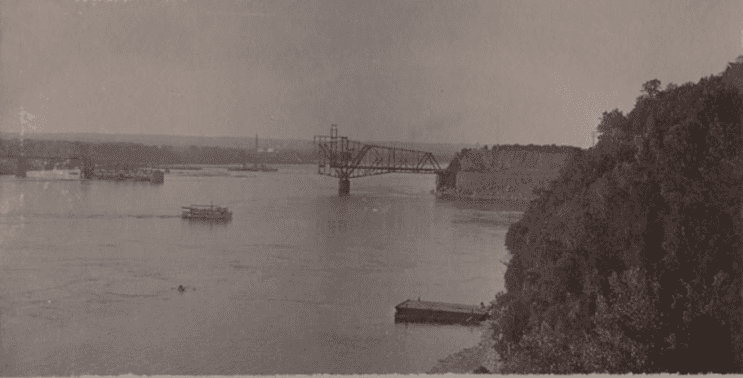

The Inter-Provincial Bridge, a.k.a. The Royal Alexandra Bridge

12 December 1900

During much of the nineteenth century, only one bridge spanned the mighty Ottawa River linking the burgeoning community of Bytown, later known as Ottawa, with its sister town of Hull on the northern shore. Initially, this was the wooden Union Bridge which was completed in 1828 close to the Chaudière Falls. That bridge collapsed a few years later and was superseded by the Union Suspension Bridge in 1843. This bridge became the main thoroughfare linking Ontario and Quebec for the rest of the century. Condemned in 1919, it was replaced by the Chaudière Bridge which is still in operation today.

In 1880, the Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway Company built a railway bridge across the Ottawa River close to Lemieux Island. Initially called the Chaudière Railway Bridge, its name was later changed to the Prince of Wales Bridge in honour of the eldest son of Queen Victoria, the future King Edward VII. (When this name change occurred is uncertain but it was no later than 1887.) However, the Prince of Wales bridge did not carry pedestrian or carriage traffic, and was far removed from the city centre.

The Inter-provincial Bridge under construction, 1900, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4459589.

The Inter-provincial Bridge under construction, 1900, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4459589.

Discussion of a new interprovincial bridge to the east of the Union Suspension Bridge actually predated the construction of the Prince of Wales Bridge. In 1877, meetings were held at Ottawa’s City Hall on the construction of a railway and carriage road bridge linking Rockcliffe in Ontario with the small Quebec community of Waterloo on the north shore of the Ottawa. The plan was for the Ottawa & Toronto Railway Company to link its rails with the Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway by way of the bridge. There were also plans to build a central depot near Elgin Street linking downtown Ottawa with the Rockcliffe bridge. But the scheme failed to gain political traction with the provincial or federal governments. Bridge supporters had hoped that governments would provide much of the $380,000 needed to fund construction.

In 1883, Sir Charles Tupper, the then Minister of Railways and Canals, put the kibosh on the proposal on the grounds that the road to the bridge had not been completed, and that the Quebec and Ontario governments had not provided any funding. Four years later, a similar proposal was mooted, with a bridge over the Ottawa at Rockland, Ontario. Supporters viewed it as an ideal Jubilee project to celebrate Queen Victoria’s golden anniversary on the throne with the suggestion that it be called the “Victoria Inter-provincial Bridge.” The idea went nowhere.

In 1890, the Pontiac & Pacific Junction Railway (P.P.J.R.) and the related Gatineau Valley Railway Company came up with a new proposal for an interprovincial bridge to link Ottawa to Hull at Nepean Point with a central depot to be built at the Rideau Canal. The price tag was estimated at roughly $800,000 including the cost of building the approaches to the bridge on both shores.

This idea was warmly greeted by important Ottawa citizens and groups, including former mayor Francis McDougal. Ottawa’s City Council, the Ottawa Board of Trade, and the Trades and Labour Council. Other communities in eastern Ontario and western Quebec later came out in support of the proposal. In 1894, the City of Ottawa taxpayers voted in favour of By-law 1,458 to give a “bonus” of $150,000 to the P.P.J.R. upon the completion of a bridge for railway, carriage and pedestrian traffic. Instead of cash, the City would hand over 30-year debentures paying an interest rate of 4 per cent. There were conditions, however. Most importantly, the inter-provincial bridge would have to be completed by July 1897.

Applications for grants also went to the Ontario, Quebec, and Dominion governments. High-powered deputations of railway and municipal officials lobbied members of legislatures. Ontario came through with $50,000 in April 1895, only a fraction of what was sought. The Quebec government chose not to provide any funds. After much delay, the Dominion government provided $212,000. In the meantime, the City of Ottawa twice extended its deadline for the railway to qualify for its $150,000 bonus.

With financing, both private and public, adequately secured, and the plans approved by the Department of Railways and Canals, work finally commenced in February 1898. The bridge would carry a single-track railway line in the centre with two carriage roads and sidewalks for pedestrians.

Including its approaches, the bridge is 2,685 feet long with a clear span of 1,050 feet, the fourth longest bridge of this type in the world at that time. Five piers were constructed to support the structure with the deepest pier located in 70 feet of water. Messrs. McNaughton & Broder were awarded the contract for building the piers. The Dominion Bridge Company of Montreal won the contract for the bridge’s superstructure. The bridge was designed by a team of Canadian engineers led by G.C. Dunn.

Bridge engineers faced some difficult challenges in building the piers owing to sunken logs and sawdust littering the river bed. Before finding bedrock for pier two, workers had to go through eight feet of drowned boards and timbers. At pier three, sawdust thirty feet deep had to be removed using a “clam-shell” dredge. While there were federal laws against fouling waterways, the law apparently did not apply to the Ottawa River—a testament to the political strength of the Ottawa Valley timber barons.

After clearing away the debris at pier two, workers discovered that the bedrock was sharply sloped. To level the area, they blasted the stone using dynamite placed in holes and attached by wires to an electric battery on Nepean Point. Reportedly, the blasts were imperceptible until smoke and bubbles came to the surface of the river. Caissons, built of twelve-inch thick wooden boards, were installed around the work sites. Into them, workers poured cement to form the base of the piers. Ten thousand barrels of cement were used in building the five piers. Stone for the masonry work came from quarries in Rockland and Eganville.

The Ottawa Approach to the Inter-provincial bridge, Nepean Point,

The Ottawa Approach to the Inter-provincial bridge, Nepean Point,

William Topley/Library and Archives Canada, PA-009430.

Another challenge that workers faced was building the approaches to the new bridge, especially on the Ontario side of the River. Labourers carved out thirty-five feet from the face of the cliff at Nepean Point to form the roadbed. A considerable portion of Major’s Hill Park was also sacrificed to make the entrance into downtown Ottawa. As well, the stone abutments of Sappers’ Bridge were pierced to provide an entry for trains into the new central train station located beside the Canal. The stone abutments were replaced by iron and steel supports that allowed for room for the trains.

Given the engineering challenges, the extensive excavation work, and delays in obtaining needed supplies, the construction of the bridge took much longer than expected. There was also the occasional labour action. In January 1900, stone cutters downed tools when their wages were cut from $3 per day prevailing during the previous summer, to $2.50 per day at the beginning of December to only $2 per day.

Because of these delays, work was hurried to ensure that conditions for the Ottawa bonus were met. Despite the haste, however, there seems to have been few accidents, and the ones that did occur were relatively minor.

Whether or not the P.P.J.R. had met all the conditions to qualify for the City of Ottawa bonus of $150,000 in debentures became contentious. Some aldermen as well as the City’s engineer maintained that the railway had failed to meet an intermediate condition of spending a minimum of $50,000 on the construction by the middle of March 1898. Consequently, they wanted to withhold the bonus. The railway said otherwise and threatened to sue. In the event, the bonus was eventually paid. There was also controversy over the nature of the bonus. Since the time the bonus was originally agreed, interest rates had fallen from 4 per cent to 3 ½ per cent. This implied that market value of the debentures had increased significantly. Instead of $150,000, the bonus was effectively worth roughly $162,000. There were unfavourable comments in the press about the City’s financial acumen in promising to give the railway company marketable debentures rather than cash.

The small announcement of the first bridge transit,

The small announcement of the first bridge transit,

12 December 1900. The Ottawa Evening Journal.

Another hiccup along the way was a proposal by a consortium of investors led by the Hull & Alymer Electric Railway to build another bridge across the Ottawa River, with the Ottawa end coming out at roughly Bank Street. The idea was to provide electric streetcar service from Hull to the Ottawa shore of the Ottawa River. The proposal was warmly greeted by both the Hull and Ottawa city councils as well as the Ottawa Retail Merchants Association, especially as the backers of the bridge were not seeking public money. However, there was strong opposition from the Inter-provincial Bridge Company, which was owned by the P.P.J.R., that argued that the new bridge would divert business away from its bridge. As well, the Ottawa Electric Railway owned by Thomas Ahearn, complained that should the Hull streetcar company provide service to Ottawa, even just to the Ontario shore of the Ottawa River, its monopoly rights would be infringed. The proposed Bank Street bridge failed to get a charter from the federal government despite several attempts.

By December 1899, the Dominion Bridge Company was ready to start building the building’s superstructure with six barge loads of steel on site. Work moved rapidly from that point. By October 1900, Ontario and Quebec were connected and work was underway in building the roadbed. Venturesome youth were spotted making the dangerous journey across the iron work from one side of the bridge to the other. On 12 December 1900, the first test train made its way over the new bridge without mishap and without fanfare. Only a small announcement in the Journal newspaper celebrated the event. A month later, Chief William F. Powell of the Ottawa Police Force and his wife were the first to drive their carriage over the bridge. They were initially stopped by a bridge guard, but were subsequently allowed to proceed when the Chief identified himself. In mid-February 1901, the inter-provincial bridge was checked out first by Dominion inspectors and subsequently by the City of Ottawa’s inspector and aldermen. Having received a positive assessment, the bridge opened to the general public for the first time at noon, 5 March 1901.

More test trains ran over the bridge, including one consisting of four heavy locomotives drawing several cars bearing heavy loads of stone and steel. Weighing more than 400 tons, far beyond the weight of a usual train, the idea was to test the endurance of the bridge. Not even the slightest tremor was felt.

Another less felicitous milestone occurred on 14 April 1901 when the bridge experienced its first accident. An approaching train spooked a horse pulling a rig occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Lahaise, the owners of a furniture store on Rideau street. The horse galloped across the bridge towards Hull and crashed into a carriage driven by Mr. and Mrs. James Cudd who were out for a pleasure drive. Mr. and Mrs. Lahaise suffered shock and bruises when they jumped from their rig to safety. Pedestrians were also sent scurrying to safety to get out of the horse’s path. While the Lahaise carriage suffered no damage, the Cudds’ buggy sustained a badly twisted wheel and back axle.

The cross-bridge train service from the Hull Station to Ottawa’s new Central Station was officially opened on 22 April 1901; scheduled service had in fact commenced four days earlier. For the big event, both bridge and train were decorated with flags and bunting. On board, were city dignitaries and railway officials. Mr. John Lauzon was the first official paying passenger. Souvenir badges were presented to all on board that inaugural seven-minute journey. Conductor Hoolihan was in charge, with engineer Mr. W. McFall. As the train rolled onto the bridge, Mr. Noe Valiquette, the proprietor of the Cottage Hotel, broke a bottle of wine on the locomotive. Huge crowds of spectators standing on the Dufferin Bridge, greeted the arrival of the train into Ottawa.

Alexandra Bridge today, by SimonP, Wikipedia.

Alexandra Bridge today, by SimonP, Wikipedia.

In August 1901, Ottawa’s Mayor William Morris suggested that the new inter-provincial bridge be called the Royal Alexandra Bridge in honour of the wife of King Edward VII. The bridge’s railway owners readily agreed with the suggestion. The bridge’s “christening” was planned for the following month when Their Royal Highnesses, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, (the future King George V and Queen Mary), came to Ottawa for the unveiling of a monument to Queen Victoria on Parliament Hill. It was proposed that the Duchess would press a button to illuminate the bridge. However, while the bridge was decked out in electric lights, which spelled out the words “Royal Alexandra Bridge” in twelve-foot letters on its side as part of the illumination of the City done specially for the Royal Visit, contemporary newspaper accounts don’t mention whether the Duchess turned the lights on. However, the royal couple did cross the bridge by carriage to visit Hull which was still recovering from the great fire of 1900.

When the Central Station, called Union Station from 1920, was closed for train traffic in 1966, the train tracks on the Alexandra Bridge were removed and the bridge converted entirely to vehicular and pedestrian traffic. In 1995, the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering designated the bridge as a National Historical Civil Engineering Site.

Today, the venerable Alexandra Bridge, the oldest bridge in service across the Ottawa River, is approaching the end of its life. Owned by the federal government, the decision has been made to replace the bridge with construction on its replacement to be completed by 2032.

Sources:

CSCE, 2022. Alexandra Bridge, Ottawa Ontario — Hull, Quebec.

National Capital Commission, 2021. Alexandra Bridge Replacement, December.

Montreal Gazette, 1995. “From The Queen City,” 11 April.

Ottawa Citizen, 1877. “The Inter-Provincial Bridge Scheme, 13 November.

——————, 1877. “The Inter-Provincial Bridge,” 14 November.

—————–, 1883. “Dominion Parliament,” 18 May.

—————–, 1887. “Queen’s Jubilee – Bridge Over The Ottawa,” 23 March.

—————–, 1895. “The Inter-provincial Bridge,”31 January.

—————–, 1997. “New Bridge For The Ottawa,” 22 November.

—————–, 1898. “Everything Arranged,” 11 January.

—————–, 1898. “Work Starts In A Few Days,” 1 February.

—————–, 1898. “Work On The Big Bridge,” 7 February.

—————–, 1898. “The First Pier Started,” 8 February.

—————–, 1900. “Work On Sapper’s Bridge,” 28 February.

—————–, 1900. “The New Bridge,” 17 November.

—————–, 1901. “Bridge Was Inspected,” 18 February.

——————, 1901. “Begun Three Years Ago,” 5 March.

——————, 1901. “The First Runaway,” 15 April.

——————, 1901. “Stood The Test,” 20 April.

——————, 1901. “Formally Opened,” 23 April.

——————, 1901. “Alexandra Bridge,” 8 August.

——————, 1901. “Alexandra Bridge,” 26 August.

——————, 1901. “The Duchess of Cornwall and York,” 21 September

Ottawa Evening Journal, 1887. “Cold Water,” 5 February 1887.

—————————–, 1893. “By-Law No. —,” 6 December.

—————————–, 1894. “Nepean Point Bridge,” 16 June.

—————————–, 1898. “Bank Street Bridge Defeated,” 14 April.

—————————–, 1898. “A Scene Of Great Activity,” 6 June.

—————————–, 1898. “A Stupendous Undertaking,” 15 October.

—————————–, 1900. “Train Over The New Bridge,” 12 December.

—————————–, 1901. “First To Drive Across,” 15 January.

—————————–, 1901. “To Be Named Alexandra,” 15 August.

Woodard, Rick. 2019. “Alexandra Bridge could be replaced within 10 years,” Global News, 19 March.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

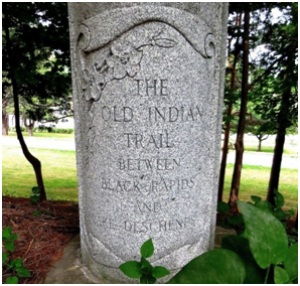

Mapping the Ottawa Valley’s Ancient Indigenous Trails

HSO Presentation Wednesday, November 17, 2021

Imagine going online 500 years ago to find something on Google Maps. You’d see no grid of streets with familiar, mostly British names; no array of colourful icons directing you to coffee shops or LRT stations. What you’d have seen then is a vast wilderness broken only occasionally by a few narrow, meandering paths. These trails were winding, not because the trail makers were lost, but because the trail makers were following the path of least resistance. To the Anishinabe traders, trappers and hunters, it made more sense to go around a steep hill rather than over it. It was easier and safer to go out of your way to cross a river at its narrowest or calmest point.

The Indigenous trails that criss-crossed the Gatineau and Ottawa valleys were ignored in later centuries by civil engineers and town planners who preferred their roads to be as straight as possible, regardless of the lay of the land. As a result, the early trailways of the Ottawa area have all but vanished, but thanks to Dr. Peter Stockdale, they’re coming back to life.

Peter is continuing his research to find the routes used by the Anishinabe, to have these trails marked with informative plaques, and where possible turned back into public trails for recreational use. Peter is the founder of Kichi Sibi Trails.

In his research, Peter has confirmed that there are different types of Indigenous trails. Portage trails cross the highland between watersheds. Ritual trails were often challenging walks that lead to remote vistas were the solstice and equinox events could be watched. There are also possible “war paths” that the Anishinabe of this area may have used as much for defence as for attack. Peter is still looking into the heritage of these types of trails.

We were also fortunate to have Barb Sarazin and Merv Sarazin join in on Peter’s discussion. Barb and Marv are current councilors of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan First Nation. Barb told a personal tale about her family and how they came to be involved in the affairs of the First Nation. Merv talked about his preferred way to get around; which is by canoe. Although land trails that Peter has been investigating were necessary to get to final destinations, the rivers and streams were the main highways for Anishinabe travelers. Merv has been making canoes since we was a child.

Find out more about the ongoing work that Peter and his team at Kichi Sibi Trails have undertaken at the Kichi Sibi Trails Facebook page.

Check out the HSO YouTube channel for a video of the full presentation.

The Grand Chaudière Dam

16 October 1868

We have in our very midst unrivalled water powers, and it would argue the utmost lack of energy, the blindest fatuity, were they to remain undeveloped. “Impressions of Ottawa,” Ottawa Citizen, 6 November 1860.

The mighty Ottawa River, also known as the Kichissippi in Algonquin and the Outaouais in French, stretches more than 1,100 kilometres. Its source is Lac Capitmichigama in central Quebec from which it runs west to Lake Timiskaming before heading south to form the boundary between Ontario and Quebec, passing through the National Capital Region on its way to meet the St. Lawrence at the Lac des Deux Montagnes in Montreal. Its watershed covers an area of more than 146,000 square kilometres.

For countless generations, the Ottawa was a key transportation and trading route for the Indigenous peoples of this land. Later, it became the route for European explorers and settlers into Canada’s interior. Led by native guides, Samuel de Champlain explored the Ottawa River in 1613. It subsequently became an important thoroughfare for French voyageurs and coureurs des bois trading manufactured goods with the First Nations for beaver and other pelts which were in high demand in Europe. Later still, loggers and lumbermen of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, who were exploiting the ancient forests of the Ottawa Valley, relied on the river to transport logs and square timber (logs that had been stripped of their bark and roughly squared) to markets.

With a vertical descent of 365 metres, the Ottawa River is turbulent and fast-flowing even today despite more than 50 dams and hydro facilities constructed along its main branch and tributaries. According to the Ottawa Riverkeeper, the Ottawa is one of the most regulated rivers in Canada. Nonetheless, it remains a magnet for white-water canoers and rafters.

For nineteenth century lumbermen trying to bring rafts of logs down the Ottawa, its rapids and falls were a nightmare, posing dangers to life and limb. However, the entrepreneurs of Ottawa and Hull saw the potential for profit from those same rapids and falls if they could be harnessed to produce the motive power necessary to drive the big saws that processed the raw lumber. By damming the Ottawa, mill owners could channel the flow of water through their mills. A tamed river also meant a safer river for the log drivers.

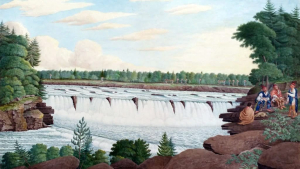

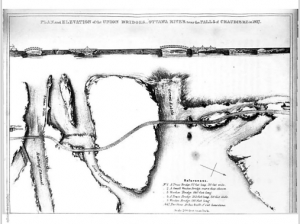

One of the major obstacles on the Ottawa River was the Chaudière Falls, known as the Giant Kettle in English. In 1829, Ruggles Wright, the son of Philemon Wright who founded Hull, built a timber slide on the Quebec side of the river to permit logs and rafts of timber to bypass the falls. Three years later, another slide was constructed by George Buchanan on the Ontario side of the river. To build the slide, a dam was constructed that ran roughly parallel to the shore to divert water into a channel. (The dam can be seen in an 1832 plan of the first Union Bridge across the Ottawa River by Joseph Bouchette.)

In 1854, at the behest of the mill-owners and lumbermen of Bytown, the Department of Public Works of the Provincial Government, constructed a 640-foot dam with log booms on the south side of the Chaudière Falls. It extended from the pier built by George Buchanan at the head of his timber slide to Russell Island above the Falls. The purpose of the dam was threefold. First, it would provide a more constant supply of water during the low water summer months. Second, it would furnish a 140-acre pool of calm water for the storage of logs waiting to be processed in the adjacent mills. Previously, only a day’s worth of logs could be stored. Third, it would reduce the loss of timber inadvertently going over the Falls. It was reported that £3,000 pounds worth of logs was lost annually owing to the timber cribs getting into the wrong channel. There was no mention of the fate of the men driving the logs.

A second dam with booms was also constructed on the north side of the river to ensure a constant supply of water for the Hull mills. According to the Citizen, “There is no limit to the extent of the commerce that may be created by the mills and factories that can be put into motion by the water of the Chaudière.”

Despite the hyperbole, the newspaper was on to something. Between 1856 and 1860, the timber industry expanded rapidly with Messrs. Perley, Booth, and Eddy joining timber pioneers such as Messrs. Baldwin, Bronson, Harris, and Young. The mill-owners sought more River “improvements” to expand their capacity. Reportedly, the lumber barons, to whom the government had leased water rights, were “exceedingly irritated and annoyed” to go with out water for their mills during the low water summer months while at the same time “a mighty volume of water [was] plunging over the Falls.” With many mills forced to close for part of the year, there was a loss of profit, especially as mill owners tried to keep skilled workers on payrolls as long as possible fearing that they might leave the region if they were laid off. Even so, many found themselves temporarily unemployed during the low water months—a serious condition as there was no unemployment insurance. The Citizen opined that “fathers of families, others younger—the hope and strength of the country—[were] standing idle, in want of work…while the mighty volume of the Ottawa rushed by the silent mills uncurbed and useless to man.”

Mr. Baldwin proposed that the government build a submerged dam across the main channel a few hundred yards above (west of) the Chaudière Falls, to divert the river towards the lumber mills. However, excess water would continue to flow over the dam during periods of high water and avert spring flooding. The government was not convinced. To allay governmental concerns about potential flooding, Baldwin suggested lowering Russell Island, located at the south end of the proposed dam, by six feet to provide an additional area of discharge during periods of high water. During low water, it would stand above the waterline and would act as an auxiliary dam. He figured that the water running over the lowered island during the spring freshet would offset the obstruction caused by the proposed dam. Still unconvinced, the Department of Public Works refused to fund the project and demanded the backers of the project, should they go ahead themselves, provide bonds of indemnity to compensate landowners who might be flooded by the dam.

With the capital for the venture provided by “a large party of the leading residents of the city and others,” the project went ahead under the supervision of Mr. John O’Connor during the fall of 1868. The submerged dam was 350 feet long and 75 feet wide at the base, tapering to 24 to 48 feet wide at the top. It was built of strong crib-work filled in with stone and braced with longitudinal timbers faced with 5-inch thick planks upon which guard timbers were attached using iron bolts. Guard piers protected each end of the dam. Reportedly, workers excavated 8,000 tons of rock, presumably from Russell Island. The project costed roughly $10,000, and was completed in five weeks using a workforce of 200 men.

The Grand Chaudière Dam was inaugurated on 16 October 1868, a day which the Citizen said would be “long remembered in the annals of the lumber interest of the valley.” The paper also praised the “enterprise of our American citizens—by whom the majority of the milling establishments at the Chaudière are owned.”

A few days later, sixty of the leading citizens of Ottawa assembled on Russell Island for a celebration to mark the completion of the dam, “and pledge a bumper to the health of the builder, and prosperity to the trade.” Chairing the gathering was Richard Scott, the Liberal member of the legislative assembly who represented Ottawa in the Ontario legislature. Other attendees included, Joseph M. Currier, the Conservative member of parliament for the City of Ottawa, Mayor Henry Friel, and a number of Dominion Government cabinet ministers despite the government’s earlier opposition to the project. Samuel Tilley, the Minister of Inland Revenue, apologized for the absence of Sir George Cartier and others who could not attend owing to important engagements elsewhere. James Skead, a prominent area businessman and senator, argued that similar works like the Chaudière dam were needed elsewhere on the Ottawa River.

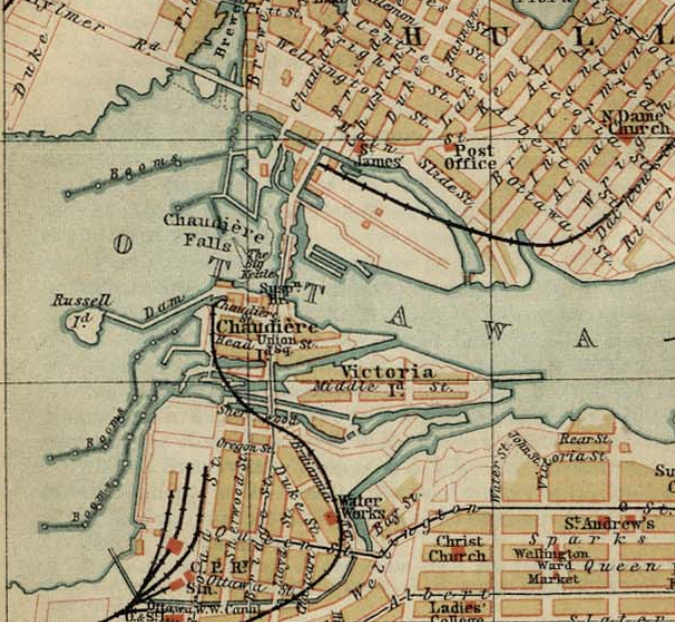

Map of the Chaudière area before the construction of the Chaudière Ring dam in 1908. The 1854 dam between Chaudière Island and Russell Island can be seen in the middle left of the map. The Grand Chaudière Dam is not visible.The impact on timber production owing to the construction of the Grand Chaudière Dam was considerable. Reportedly, the small mill owned by Mr. Young increased its monthly production by 1 million feet of lumber, the product of 5,000 standard logs, during the first dry season after the completion of the dam. Extrapolating these figures to include the much larger operations of Messrs. Baldwin, Bronson, Booth and Perley, the Citizen calculated that a total of 13 million additional feet of lumber were produced every month during the dry season. With a dry season averaging three months, the value of increased production amounted to an estimated $507,000 dollars—a huge sum. As well, there was no flooding during the spring freshet as feared by the government. The expectations of the dam’s backers were more than fully met.

Map of the Chaudière area before the construction of the Chaudière Ring dam in 1908. The 1854 dam between Chaudière Island and Russell Island can be seen in the middle left of the map. The Grand Chaudière Dam is not visible.The impact on timber production owing to the construction of the Grand Chaudière Dam was considerable. Reportedly, the small mill owned by Mr. Young increased its monthly production by 1 million feet of lumber, the product of 5,000 standard logs, during the first dry season after the completion of the dam. Extrapolating these figures to include the much larger operations of Messrs. Baldwin, Bronson, Booth and Perley, the Citizen calculated that a total of 13 million additional feet of lumber were produced every month during the dry season. With a dry season averaging three months, the value of increased production amounted to an estimated $507,000 dollars—a huge sum. As well, there was no flooding during the spring freshet as feared by the government. The expectations of the dam’s backers were more than fully met.

With the mills working at full capacity from the beginning to the end of the milling season, the Citizen wrote: The completion and successful working of the dam may be said to be the crowning point of numerous victories over great natural obstructions and difficulties. The vast water power which has for ages been conserved in the Chaudière Falls, has now been utilized to an extent which few of the last generation ever dreamt of, and which but few of the present generation, who thoroughly understood the difficulties, could, a few years ago, have supposed could be realized.

Today, the Grand Chaudière Dam, which permitted a huge expansion of the Ottawa timber business during the second half of the nineteenth century, is long gone. It was replaced by the Chaudière Ring Dam in 1908 which massively expanded the hydro-electric generating capacity of the Chaudière Falls, and provided the bulk of Ottawa’s electricity during the early twentieth century.

Sources:

Haxton Tim & Chubbuck, Don, 2002, Review of the historical and existing natural environment and resource uses on the Ottawa River, Ontario Power Generation, www.ottawariverkeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/tim_haxton_report.pdf.

Ottawa Citizen, 1854. “No Title,” 29 July.

——————, 1854. “Ottawa Improvements,” 7 October.

——————, 1854. “Public Works On The Ottawa,” 28 October.

——————, 1868. “Inauguration Of The Great Chaudiere Dam,” 23 October.

——————, 1869. “The Pubic Works on the Ottawa And Its Tributaries,” 12 August.

——————, 1869. “The Lumbering Interests Of Ottawa, 16 August.

Ottawa Riverkeeper, 2019. Dams, www.ottawariverkeeper.ca/home/explore-the-river/dams/.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Tunney’s Pasture - The Story Behind Ottawa’s Field of Dreams