Rick Henderson – The Capital Builders

Rick Henderson is the great-great-great-great-grandson of Philemon Wright & Abigail Wyman and author of "Capital Chronicles".

Rick recounts the history of the region in four parts:

- The Curious Cast that Created Canada's Capital

- Bridging the Divide

- Canada's Capital - Set in Stone

- A Capital Route - Canal

Epi(b)logue - The Inglorious End of Two Glorious Men

Paul Weber – Stories in Song

Paul Weber is a bilingual singer-songwriter, guitarist, storyteller and videographer who likes to share Ottawa history in song.

In this 3½ minute video, Paul performs an ode to the workers who toiled on construction of the Rideau Canal, completed in 1832: Three Years on the Rideau Canal.

In this one-minute video, Paul finds remains of a bridge in the Rideau River, and traces that bridge back to first railroad to reach Bytown, the Bytown and Prescott Railway, the first train arriving on Christmas Day, 1854: Rideau River Train Bridge Ruins.

Andrew King – Boats, Taverns, and Beer

Andrew King is an Ottawa artist and historian and author of the Ottawa Rewind blog.

- Andrew recalls the steamships that once plied the Rideau Canal: The Lost Steamships of The Rideau Canal (May 22, 1832)

- Andrew unearths the Firth Tavern: Ottawa's First Pub (1819)

- Thirsty canal workers? Andrew combs through old maps to track down Bytown’s first brewery: Ottawa First Brewery (1831)

George & Iris Neville – Dr. A. C. Christie’s Travels 1830-1833

These transcriptions of Dr. Christie’s travel writings (1830-1833) along the Ottawa River and Rideau Canal provide a unique perspective into that early era.

From the HSO Bytown Pamphlet series:

107. Ottawa River Settlements in 1833 as described by Dr. Alexander J. Christie

Travel writings from 1833 by Dr. Alexander Christie. Reflecting on current events, Dr. Christie describes the settlements, land quality for agriculture, and lumbering and mineral resources of townships adjacent to the Ottawa River between Pointe-Fortune in the lower Ottawa River Valley and the McNab and Clarendon/Bristol settlements upriver. Transcriptions by George A. and Iris M. Neville.

072. Rideau Canal & Bytown Memoranda by Dr. A.J. Christie, Physician to the Rideau Canal Works

Memoranda of a journey from Kingston to Bytown made along the Route of the Rideau Canal, in February 1830. Written by Dr. A.J.Christie. Transcribed by George A. Neville & Iris M. Neville.

(Historical Language Advisory: Certain parts of the HSO pamphlet series may contain historical language and content that some may consider offensive, for example, language used to refer to racial, ethnic, and cultural groups. These items, their content and descriptions, reflect the time period in which they were created and the viewpoint of their author. The items are presented with their original text to ensure that attitudes and viewpoints are not erased from the record.)

John Morrison – The Rideau Canal - A Poem

John Morrison lived in Manotick from 1994 to 2005 where he spent many happy hours paddling the area waterways and viewed the river and the canal as his own little piece of heaven on earth.

The Rideau Canal

A curtain does fall, so majestic and proud

Such a natural wonder, so gracious a shroud

Like a powerful train of glory descends

As a continuous fall at the Outaouais end

A fire alights from the south it did spread

To the north like a plague through the heart it has bled

With a mawkish like cry for freedom and joy

But freedom’s best chance was a fraudulent ploy

From a flicker of flame to a firestorm bred

Death escalates through a life cycle of dread

And taming this shrew with its penchant for blood

Was a foolish man’s bait for poor Madison’s club

Yet a fire would spread in a harrowing scene

From a spark it would roar with a devilish scream

From Niagara, on east, to a Forty Mile Creek

To a nondescript farm and a Chateauguay sneak

From Queenstown to Lundy, Detroit and the Thames

The Boxer and Enterprise, surrender of Maine

Through Ohio and Plattsburg, to a Moravian town

The war it did rage for Miss Liberty’s crown

Cities would fall and the towns they would burn

First Newark then York; it was Washington’s turn

War’s firebrand eyes thrust farther to yield

And finally burn in an Orleans field

What came but a draw in this foolish man’s quest?

For power and glory are such meaningless guests

Whatever the gain from the lives that were lost

For the hawkish bent men who lied at great cost

And the curtain still fell, so majestic and proud

As if sensing the chaos, so soothing its sound

Like the rapturous strains of a torrent, transcends

To emerge as a call at the Outaouais end.

***

The years fell away, and the anger did wane

Rush-Baggot had calmed such a petulant strain

An American age brought prosperity’s peace

As a confidant pace of change was unleashed

But the land to the north so upright and proud

Was paranoid still to the south’s freedom sound

A country that cried for security’s calm

Yet stands all alone ‘against a threatening psalm

But this land full of lakes and rivers and streams

Was a natural course for a military dream

For fear set in stride a magnificent quest

To build a canal that was strategically blessed

While the mighty St Laurence was a natural draw

It was fraught with real danger from its rapid rock falls

And upstream it ran with a thunderous roar

Too close to the south with its threatening core

The Ottawa ran to St Laurence’s call

To strike from the north and a western landfall

An historical route that opened the west

Where the traders would meet at the curtain for rest

Two rivers did run from a common high ground

To the south and the north from Lake Rideau their sound

From the shallows and falls through the marshes and swamps

From King’s town to Wright’s town, two rivers as one

To build a canal through this wilderness screams

Of a madness and curse of the military’s dream

A task so immense, so daunting and brash

That only the British could fathom this task

But the British did find a man of the Corp

A Wellington man from the Peninsular War

A man who had held the Canadian Shield

So right for this task with indefatigable zeal

John By was a Colonel and a leader of men

Ahead of his time and a genius, well bred

An engineer’s man with a passionate streak

For simplicity’s beauty with its functional tweaks

With orders to build a navigable path

From the Outaouais south to Ontario’s wrath

To rise from a bay named the Entrance - way crept

Up flight after flight, like some nautical steps

A plan was developed and contracts were signed

Engineering so simple with symmetrical lines

Pure genius at work with a heavenly hand

To guide and instruct a magnanimous man

With Drummond and Redpath, Phillips, MacKay

Canadian contractors, strong men of their day

These artists of stone were men of their word

So forthright and loyal to the Colonel’s accord

The sappers and miners and mason’s stones lay

Stonecutters and woodmen, all of the trades

For comfort, their spirit; their love of the crown

Romantic and colourful, these men of the realm

But the marvelous work that was soon to unfold

Was dependent upon the poor labourer’s code

The back wrenching work to clear out the land

And dig such a ditch with just spades in their hands

Such men from hard times, forever were cursed

To fight for survival and work through their thirst

Through backbreaking strains as their calloused hands scream

As they toiled and they toiled for this military dream

The Frenchmen held sway with their skill and savvy

So noble these men and their role as navvies

Independence of mind with a will to succeed

Just pride in their work and their songs and their deeds

But an Irishman’s fate to arrive at this place

To rescue one’s life from some wretched like fate

The scourge of the earth in the Englishman’s eye

Forgotten at home, they severed all ties

For a pestilence spread to drive them afar

From an emerald isle to this devil’s back yard

Though beauty may rest on the eye from beyond

A hellish nightmare was reality’s song

Just rags on their backs with their wives by their side

With children so weak from starvation and pride

A thousand would fall from a dengue-ish like hue

And die from this work’s laborious flu

Poor brothers would cry as their graves had been marked

So blind to the danger and the peril from sparks

As the powder was set with a magical link

Their lives were extinguished from the death blast’s cruel drink

Yet the lakes and the streams, swift water, rock falls

Were captured and tamed by this engineer’s call

Magnificent feats what By had achieved

In this harsh, hellish wilderness, was hard to conceive

The entrance way blessed by a protestant prayer

The first stone was set by John Franklin with care

Not mindful as yet that his greatness was cast

To die in the Arctic from an arctic cold blast

The curse of Hog’s Back; an Isthmus scourge

The tranquility of Chaffey’s; Long Island was purged

At Burritt’s and Black, these rapids were tamed

And Merrickville’s beauty, a religious refrain

With names like Poonamalie, with its cedar incense

An Indian aura in a wilderness sense

Opinicon’s names and a Cranberry fog

The curse of the labourer to die in this bog

The dam at the falls known locally as Jones

Is a testament still to its magnificent stone

Block upon block in a crescent like stance

Like a rampart of genius or an engineer’s dance

The work underway, six years to progress

The locks were completed, and the dams were well dressed

Through steamy hot summers, through sweat and death’s fear

Through winter’s ice jams; hell’s nightmare those years

The locks and the dams, wastewater and weirs

The cut at the entrance, eight steps to the piers

The breadth of this work remains unfathomable, sealed

As a masterpiece set in the Canadian Shield.

***

The threat from the south was all but contained

For the status quo boundary was all that was gained

From the firestorm set in those years long ago

Extinguished for good as a friendship would grow

Poor tragedy’s mark on this cornerstone lay

On the heart of a man who held the Rideau at bay

Called back by a King who questioned his deed

A question of funds from some zealot to heed

An inquiry would set the tone through the years

To diminish By’s feats; he was ignored by his peers

His spirit would die from his countrymen’s chill

And not from the bog or the Isthmus ills

Yet his legacy flows for our nation to see

Wonderment still, a magnificent deed

To balance such beauty with a functional stream

Through a Canadian wilderness with just minimal means

But the jewel in the crown of this engineer’s quest

Was not the canal or a technical best

For a town that was born on the Outaouais scene

In this land full of lakes and rivers and streams

By the Barracks Hill shanty near the Sapper’s stone bend

A magnificent tower of peace would ascend

From a lower town swamp to an upper town’s view

A great city would grow with great values imbued

For this capital’s crown of achievement remains

From the peaceful green flow of the Rideau, contained

The seeds of a city and a national theme

To build a great country with the freedom to dream

And the curtain still falls, so majestic and proud

Like a sentinel’s call or a passionate bow

For the genius who toiled on the Outaouais scene

And left such a mark with this beautiful stream.

© 2007 John Morrison, Mill Bay BC

Curtis Wolfe – William Tormey

Curtis Wolfe researches local history and heritage and his writings have been featured in Lowertown’s Community Newspaper The Echo.

Curtis uncovers the history of a local street: What’s in a name? Uncovering the namesake of Tormey Street.

The HSO 2026 Bytown200 Bicentennial Storytelling Challenge

Let’s hear your stories about Bytown and the Rideau Canal as we begin to mark 2026, the 200th anniversary of the beginning of both!

All contributions are welcome. Selected submissions will be shared on a special webpage on the HSO website for all to access, including educators. Eligible contributions can be submitted in a variety of formats, including written or audio/video.

We hope to also incorporate selected contributions into our many other platforms – such as our blog, the HSO Capital Chronicle newsletter, website articles and the Ottawa Stories sections and potentially our pamphlet series. All will be shared through our social media platforms well.

We welcome stories that pertain to the Rideau Canal or Bytown (1826-1855) or the Ottawa area’s history beforehand, as well as stories exploring the impact that the establishment of both had on the lives and livelihoods of Indigenous people.

We welcome new as well as updated or previously-published materials for submission. Contributors will allow HSO the right to publish their materials while also retaining the right to do so themselves.

Contact us to learn more: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

We will also be happy to discuss any proposals for submissions you may have.

Have a look at our collection of stories: www.historicalsocietyottawa.ca/resources/bytown-200

Museum Club Visit to Merrickville

The third Museum Club outing took place on Thursday, July 18, 2024, when a dozen registered participants, and two “foundlings” received a guided tour of the Merrickville Blockhouse Museum from our host, Jane Graham, who is the President of the Merrickville & District Historical Society (MDHS). Jane explained that the Blockhouse was built in 1832 to defend the Rideau Canal but never served in its original role. Instead, it became the home of the first lockmaster, Sgt. Johnston, his wife and children. Over the years the Blockhouse has had many other uses including as a storage facility and a church. Eventually it fell into disrepair and was scheduled to be demolished in the early 1960s. It was saved by the community of Merrickville who raised funds and created the Merrickville & District Historical Society to restore and operate the Blockhouse. The work has since become more than the volunteers of the MDHS can realistically handle, so the Town of Merrickville has now assumed responsibility for the Blockhouse Museum.

After about an hour in the Blockhouse Museum, Jane led ten of us on a guided walking tour along the main street of Merrickville pointing out many of the historic buildings and telling us the stories behind each. Jane told us some of the details of the history of Merrickville itself, from its origin as a thriving industrial and commercial hub, through its decline into the mid twentieth century and its renaissance in the past few decades as a vibrant community and a haven for artists and artisans of all kinds. She also told us some colourful stories of a number of its more prominent early residents and of the plans of the MDHS to honour one of these, Harry McLean, with a statue. The weather was perfect for the walking tour and there was much to see and yet more that could be explored independently based on a walking tour guide that is available through their web site.

Following our walking tour, which lasted just over an hour, we said good bye to Jane and retreated to the Mainstreet Restaurant, across the street from the Blockhouse, where the ten of us were warmly greeted. The large menu offered many tasty choices and their own lager was enjoyed by a number of our party. After lunch, the group dispersed, some browsing, and buying, in Merrickville’s fascinating array of shops.

Museum Club provides an opportunity for its participants to make new connections or in some cases discover existing connections they did not know they already had. The latter occurred on our Merrickville trip when a casual lunchtime discussion revealed that one of the participants knew the grandparents of another, even though the two participants had never met and the grandparents live in south-western Ontario. As they both agreed, it is a small world.

One of the goals of the Museum Club is to strengthen the relationships between the Historical Society of Ottawa and other organisations involved in the exploration of our local history or in preservation and conservancy. To this end, a partnership is now being established between the HSO and the MDHS whereby the MDHS will send the HSO electronic copies of their newsletters and invitations to their speaker series presentations and the HSO will reciprocate, providing more opportunities for the members of both organizations.

The Final Demise of the Last Remnant of Dow’s Great Swamp

Most of us think of “Dow’s Swamp” as having disappeared during the construction of the Rideau Canal, two centuries ago, leaving us with what we know today as “Dow’s Lake”.

But did you know that a remaining southern portion of Dow’s Swamp continued to thrive until Ottawa’s ever-expanding urban footprint brought about the final destruction of this vital and vibrant vestige of wetland in the 1950s?

Long-time naturalist and plant ecologist Joyce Reddoch reminds us of our tragic loss of that precious remnant of primaeval ecosystem, as is illustrated in the attached collection of articles, including a post-mortem of her own, published in a journal of the Ottawa Field Naturalists’ Club almost a half century ago.

Scientific studies show that this now-gone swamp – a low trough between Dow’s Lake and the Rideau River, bounded on the west by the old CPR track and on the east by the old Bronson Avenue – was a lake from about 7,000 until about 3,000 years ago when bog and swamp forest began to form, finally becoming tree-covered 1,000 to 1,500 years ago.

(A swamp is generally a wetland or peatland with standing water or water gently flowing through pools or channels. The water is rich in nutrients and the vegetation is characterized by a dense cover of deciduous or coniferous trees and shrubs, herbs and mosses. Oft-misunderstood and underappreciated, our swamps are crucial to maintaining biodiversity.)

John MacTaggart, Colonel By’s chief engineer observed of Dow’s Swamp in 1829 that “the cedar-trees… grow as thickly in the swamp as they possibly can grow, an average fourteen inches thick and seventy feet high”.

In the century+ old Ottawa Field Naturalists’ Club’s earlier days, this remaining southern remnant of Dow’s Swamp was cherished as a seemingly inexhaustible refuge for sightings of rare and flourishing flora and fauna, including rare and endangered orchids, rare butterflies, birds and frogs and other wildlife.

The terrain of Dow’s Swamp, as it still existed earlier last century, was well-described by renowned Canadian forester/zoologist C.H.D. Clarke as he noted the birds he had spotted “there, among the cedars, willows, alders and elms, in tangled glades that led over sodden ground to beds of cattails”.

More than a dozen species of native orchids had been excitedly recorded in this now-disappeared remnant of the Dow’s Swamp wetland complex. Alder flycatchers, Lincoln's sparrows, white-throated and clay-coloured sparrows, rusty blackbirds, ruby-crowned kinglets, veeries, vireos, scarlet tanagers, waterthrushes, warblers, Carolina and marsh wrens, purple finches and black ducks were among the sometimes-scarce birds that Dr. Clarke and other avid naturalists would add to their observation lists.

Through these attached articles, Dr. Reddoch invites us to better understand that swamps, in their undamaged state, are ecosystems crucial to the maintenance of ecological diversity (and for maintaining ground water levels) – not dismal, stagnant, fetid places as per our popular misconceptions.

(Even mosquitoes – such as those who had likely persuaded the Dow family to abandon their allotment in 1826 – perform crucial roles as plant pollinators and food for birds.)

Dow’s Swamp is a lost ecological gem that Joyce Reddoch urges us never to forget.

(As we mourn the loss of this one small urban-enclosed portion of primaeval wilderness, one can only reflect on the impact post-contact settlement has had across our nation, not only on the long-existing flora and fauna, but also on the Indigenous people, upon this land their lives and livelihoods had vitally depended.)

Here are the articles that Joyce has kindly provided for us to read and learn more:

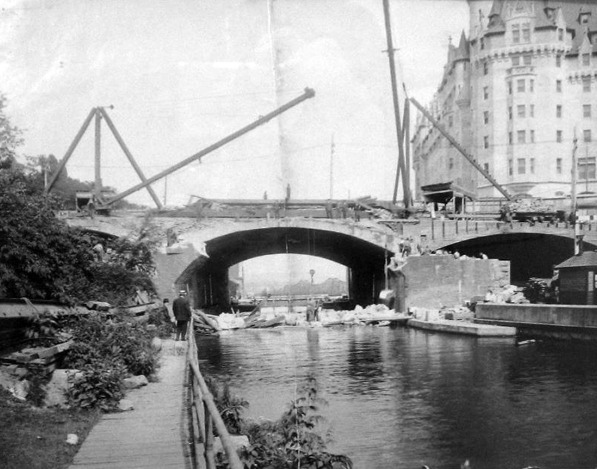

Sappers' Bridge

23 July 1912

It ended with a crash that sounded like a great gun going off, the noise reverberating off the buildings of downtown Ottawa. After faithfully serving the Capital for more than eighty years, Sappers’ Bridge finally succumbed to the wreckers in the wee hours of the morning of Tuesday, 23 July 1912. However, the old girl didn’t go gently into that good night. It took seven hours for the structure to finally collapse in pieces into the Rideau Canal below. After trying dynamite with little success, the demolition crew rigged a derrick and for hours repeatedly dropped a 2 ½ ton block onto the platform of the bridge before the arch spanning the Canal gave way. Mr. O’Toole the man in charge of the demolition, said that the bridge was “one of the best pieces of masonry that he [had] ever taken apart.”

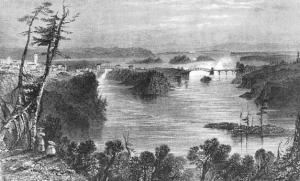

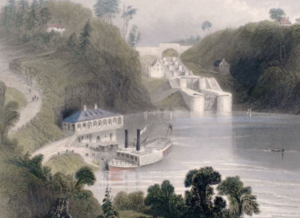

View of the Rideau Canal and Sappers’ Bridge – Painting by Thomas Burrowes, c. 1845, Archives of Ontario, Wikipedia.The bridge, the first and for many decades the only bridge across the Rideau Canal, dated back to the dawn of Bytown. In the summer of 1827, Thomas Burrowes, a member of Lieutenant Colonel John By’s staff, gave his boss a sketch of a proposed wooden bridge to span the Rideau Canal, which was then under construction, from the end of Rideau Street in Lower Bytown on the Canal’s eastern side to the opposing high ground on the western side. Colonel By accepted the proposal but opted in favour of building the bridge out of stone rather than wood. Work got underway almost immediately, with the foundation of the eastern pier begun by Mr. Charles Barrett, a civilian stone mason, though the vast majority of the workers were Royal Sappers and Miners. On 23 August 1827, Colonel By laid the bridge’s cornerstone with the name Sappers’ Bridge cut into it. The arch over the Canal was completed in only two months. On the keystone on the northern face of the bridge, Private Thomas Smith carved the Arms of the Board of Ordnance who owned the Canal and surrounding land. The original bridge was only eighteen feet wide and had no sidewalks.

View of the Rideau Canal and Sappers’ Bridge – Painting by Thomas Burrowes, c. 1845, Archives of Ontario, Wikipedia.The bridge, the first and for many decades the only bridge across the Rideau Canal, dated back to the dawn of Bytown. In the summer of 1827, Thomas Burrowes, a member of Lieutenant Colonel John By’s staff, gave his boss a sketch of a proposed wooden bridge to span the Rideau Canal, which was then under construction, from the end of Rideau Street in Lower Bytown on the Canal’s eastern side to the opposing high ground on the western side. Colonel By accepted the proposal but opted in favour of building the bridge out of stone rather than wood. Work got underway almost immediately, with the foundation of the eastern pier begun by Mr. Charles Barrett, a civilian stone mason, though the vast majority of the workers were Royal Sappers and Miners. On 23 August 1827, Colonel By laid the bridge’s cornerstone with the name Sappers’ Bridge cut into it. The arch over the Canal was completed in only two months. On the keystone on the northern face of the bridge, Private Thomas Smith carved the Arms of the Board of Ordnance who owned the Canal and surrounding land. The original bridge was only eighteen feet wide and had no sidewalks.

Reportedly, one of the first civilians to cross Sappers’ Bridge was little Eliza Litle (later Milligan), the six-year old daughter of John Litle, a blacksmith who had set up a tent and workshop where the Château Laurier Hotel stands today. Apparently, Eliza was playing close to the Canal bank on the western side when she was frightened by some passing First Nations’ women. She ran screaming towards Sappers’ Bridge which was then under construction. A big sapper picked Eliza up and carried her over a temporary wooden walkway and dropped her off at her father’s smithy.

Back in those early days, there were two Bytowns. Most people lived in Lower Bytown. It had a population of about 1,500 souls, mostly French and Irish Catholics. The much smaller Upper Bytown, which was centred around Wellington Street roughly where the Supreme Court is situated today, had a population of no more than 500. This was where the community’s elite lived, mainly English and Scottish Protestants. The two distinct worlds, one rowdy and working class, the other stuffy and upper class, were linked by Sappers’ Bridge. While the bridge joined up Rideau Street on its eastern side, there was only a small footpath on its western side. The path wound its way around the base of Barrack Hill (later called Parliament Hill), which was then heavily wooded, past a cemetery on its south side that extended from roughly today’s Elgin Street to Metcalfe Street, until it reached the Wellington and Bank Streets intersection where Upper Bytown started. It wasn’t until 1849 that Sparks Street, which had previously run only from Concession Street (Bronson Avenue) to Bank Street, was linked directly to Sappers’ Bridge. During the 1840s, that stretch of path to Sappers’ Bridge was a lonely and desolate area. It was also dangerous, especially at night. It was the favourite haunt of the lawless who often attacked unwary travellers. Many a score was settled by somebody being turfed over the side of the bridge into the Canal. People travelled across Sappers’ Bridge in groups: there was safety in numbers.

Bytown, which became Ottawa in 1855, quickly outgrew the original narrow Sappers’ Bridge. In 1860, immediately prior the visit of the Prince of Wales who laid the cornerstone of the Centre Block on Parliament Hill, six-foot wide wooden pedestrian sidewalks supported by scaffolding were added to each side of the existing stone bridge. This permitted the entire 18-foot width of the bridge to be used for vehicular traffic.

But only ten years later, the bridge was again having difficulty in coping with traffic across the Rideau Canal. There was discussion on demolishing Sappers’ Bridge and replacing it with something much wider. The Ottawa Citizen opined that such talk verged on the sacrilegious as Sappers’ Bridge was “an old landmark in the history of Bytown.” The newspaper also thought that it was far too expensive to demolish especially as the bridge had “at least another century of wear in it.” It supported an alternative proposal to build a second bridge over the Canal.

In late 1871, work began on the construction of that second bridge across the Canal linking Wellington Street to Rideau Street, immediately to the north of Sappers’ Bridge. It was completed at a cost of $55,000 in 1874. It was called the Dufferin Bridge after Lord Dufferin, Canada’s Governor General at that time. Another $22,000 was spent on widening the old Sappers’ Bridge on which were laid the tracks of the horse-drawn Ottawa Street Passenger Railway.

Despite the upgrade, Ottawa residents were still not happy with the old bridge. Sappers’ Bridge was a quagmire after a rainstorm. On wag stated that “It is estimated that the present condition of the bridge has produced more new adjectives that all the bad whiskey in Lower Town.” One Mr. Whicher of the Marine and Fisheries Department was moved to write a 24-verse parody of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem The Bridge about Sappers’ Bridge. In it, he referred to “many thousands of mud-encumbered men, each bearing his splatter of nuisance.” He hoped that a gallant colonel “with a mine of powder, a pick and a sure fusee (sic)” would blow it up. His poem was well received when he recited it at Gowan’s Hall in Ottawa.

But it took another thirty-five years before the government contemplated doing just that. As part of Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s plan to beautify the city and make Ottawa “the Washington of the North,” the Grand Trunk Railway began in 1909 the construction of Château Laurier Hotel on the edge of Major’s Hill Park, and a new train station across the street. Getting wind of government plans to build a piazza in the triangular area above the canal between the Dufferin Bridge and Sappers’ Bridge in front of the new hotel, Mayor Hopewell suggested that Sappers’ Bridge might be widened as part of these plans in order to permit the planting of a boulevard of flowers and rockeries to hid the railway yards from pedestrians walking over the bridge. He also added that public lavatories might be installed beneath the piazza.

Demolition of Sappers’ Bridge, 1912. The arch of Sapper’s bridge is gone leaving only the broken abutments and rubble in the Canal. The newly built Château Laurier hotel in in the background on the right. Dufferin Bridge is in the centre of the photograph. Bytown Museum, P799, Ottawahh.In the event, the federal government decided to demolish Sappers’ Bridge. Both the Dufferin and Sappers’ Bridges were replaced by one large bridge—Plaza bridge. This new bridge was completed in December 1912. The piazza over the Canal was also built. It was bordered by the Château Laurier Hotel, Union Station, the Russell House Hotel and the General Post Office. A straw poll conducted by the Ottawa Citizen newspaper of its readership, favoured naming the new piazza “The Plaza.” However, the government, the owner of the site, had other ideas. It decided on calling it Connaught Place, after Lord Connaught, the third son (and seventh child) of Queen Victoria who had taken up his vice-regal duties as Canada’s Governor General in 1911.

Demolition of Sappers’ Bridge, 1912. The arch of Sapper’s bridge is gone leaving only the broken abutments and rubble in the Canal. The newly built Château Laurier hotel in in the background on the right. Dufferin Bridge is in the centre of the photograph. Bytown Museum, P799, Ottawahh.In the event, the federal government decided to demolish Sappers’ Bridge. Both the Dufferin and Sappers’ Bridges were replaced by one large bridge—Plaza bridge. This new bridge was completed in December 1912. The piazza over the Canal was also built. It was bordered by the Château Laurier Hotel, Union Station, the Russell House Hotel and the General Post Office. A straw poll conducted by the Ottawa Citizen newspaper of its readership, favoured naming the new piazza “The Plaza.” However, the government, the owner of the site, had other ideas. It decided on calling it Connaught Place, after Lord Connaught, the third son (and seventh child) of Queen Victoria who had taken up his vice-regal duties as Canada’s Governor General in 1911.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the beautification of downtown Ottawa continued. The Federal District Commission, the forerunner of the National Capital Commission, expropriated the Russell Block of buildings and the Old Post Office to provide space for a national monument to honour Canada’s war dead. The war memorial was officially opened in 1939 by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. In the process, Connaught Place was transformed into Confederation Square.

Little now remains of the old Sappers’ Bridge. Hidden underneath the Plaza Bridge is a small pile of stones preserved from the old bridge with a plaque installed by the NCC in 2004 in honour of Canadian military engineers. The bridge’s keystone with the chiselled emblem of the Ordnance Board was also saved from destruction. For a time it was housed in the government archives building but its current location is unknown.

Sources:

Ross, A. H. D. 1927. Ottawa Past and Present, Toronto: The Musson Book Company.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1871. “editorial,” 3 May.

————————, 1972. “A Dirty Bridge,” 10 April.

————————, 1874. “Sappers’ Bridge,” 9 October.

————————, 1913. “‘Connaught Place’, Cabinet’s Choice of Name for Area Formed By Union of Sappers’ and Dufferin Bridges,” 24 March.

————————, 1925. “Muddy Sappers’ Bridge In the Seventies,” 18 July.

———————–, 1928. “Girl of Six Was the First Female To Cross Sappers’ Bridge Over Canal,” 23 June.

The Ottawa Evening Journal, 1910. “Widening of the Bridges,” 3 June.

———————————–, 1912. “Early Days In Bytown Some Reminiscences,” 27 April.

———————————–, 1912. “When Ottawa Was Chosen The Capital of Canada,” 4 May.

———————————–, 1912. “Bridge Is Blown Down,” 23 July.

———————————–, 1914. “Notable Stones In the History Of The Capital,” 16 March.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.