Poulins: Ottawa's Store of Satisfaction

2 February 1929

L. N. Poulin, Ltd, known to all as simply Poulin’s, ranked among the finest retail stores in Ottawa during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was known for excellent service, fair dealing, innovative advertising methods, and low prices. During its early years it billed itself as “Ottawa’s most progressive store.” Later, it styled itself as “Ottawa’s store of satisfaction.”

For forty years, the store stood at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets in the heart of the capital’s business district. Then, out of the blue, L. N. Poulin, its founder, announced in late 1928 that he was retiring and that the store would close. Within two months, the grand retailer was gone, shutting its doors for the last time on 2 February 1929 after a month-long “Retiring from Business Sale.” Other than his retirement—L. N. Poulin was 70 years of age at the time—no other reason was cited for the closure. Poulin rented his building on a long-term lease to Schulte-United Corporation of 485 Fifth Avenue New York, a thrusting, new firm that was opening “five and dime” stores across North America.

Poulin’s was started in 1889 by Louis Napoleon Poulin and his wife Mary Poulin (née McEvoy). Mme Poulin is given little credit for starting the firm in contemporaneous accounts (not surprisingly given the times) but her obituary noted that she was a considerable businessperson in her own right. L. N. Poulin was born in 1858 in a log home in Addison, Ontario, near Brockville. At age thirteen, he got a taste of retail selling by doing chores and odd jobs at Messrs. Nichols and Parker in the nearby town of Toledo. At sixteen, he took a train to Ottawa to make his fortune. Apparently, he had a return ticket to Brockville in his pocket should things go wrong. He didn’t need it.

In Ottawa, he found employment with Russell, Gardiner & Legatt, one of the largest merchant firms in the capital. He worked there, and at another firm, Stitt & Company, for eleven years before he and his wife struck out on their own in 1889; the couple had married in 1884. Most accounts of Poulin’s early years place his store in a small frame building at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets, a location that he occupied in bigger and bigger establishments for the next 40 years. However, there are newspaper references to a L.N. Poulin dry goods store at 99 Bank Street through the 1889-90 period. The company ran an advertisement for a “removals sale” in the Ottawa Evening Journal in early April 1890. This suggests that it was about then that the Poulins made the move to their permanent home at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets.

Mr. L. N. Poulin, Ottawa Citizen, 18 June 1923. Poulin, aided by two assistants, rented 600 square feet on the ground floor of the building from John A. Brouse for $50 per month. The budding dry goods firm only had $4,000 worth of stock. One of his first customers was reportedly Lady Macdonald, the wife of Sir John A. Macdonald.

Mr. L. N. Poulin, Ottawa Citizen, 18 June 1923. Poulin, aided by two assistants, rented 600 square feet on the ground floor of the building from John A. Brouse for $50 per month. The budding dry goods firm only had $4,000 worth of stock. One of his first customers was reportedly Lady Macdonald, the wife of Sir John A. Macdonald.

The firm was a success. In 1892, Poulin bought the Brouse property which also housed the Dymond shirt factory and the YMCA. Two years later, he took over two buildings to the west on Spark Street (the Bush-Bonbright store and National Manufacturing Company) and purchased a milk factory at the rear on O’Connor Street. In 1902, Poulin bought more property on Spark Street giving him 132 feet of frontage. In 1906, he expanded further, buying the Mills Hotel from the Misses Piggott to the rear of his property which gave him a uniform depth of almost 100 feet. Two years later he acquired the J.M. Garland property on O’Connor Street with a view to future expansion. In 1915, this became the store’s house furnishings annex.

By 1923, the store had more than 73,000 square feet of floor space, with stock valued at close to $500,000. It employed 245 people. That year, the enterprise expanded for the last time, demolishing the old annex and erecting a four-storey extension which added an additional 18,000 square feet of floor space. This new structure was integrated with the original main building. Looking to the future, it was constructed in a fashion that allowed for six more storeys to be added at a later date.

The store was noted for its innovative approach to advertising. One spectacular example of this occurred during the summer of 1904. Poulin’s announced its “Lucky Money Back Sale.” A date during a six-week period was selected at random by Mayor Ellis and place in a sealed envelope in the vault of the Bank of Ottawa. Neither the Mayor, the bank manager, or Mr. Poulin knew the selected date. All sales on that date would be refunded in full. Poulin advised customers to shop at his store every day of the sale to ensure being a winner. At the end of the sale, the sealed enveloped was open and the lucky date revealed—23 August, 1904. All customers on that date were given three days to return to the store with their sales receipts to “receive “the full amount of your checks in NEW, CRISP MONEY.”

Poulin’s Sale, Ottawa Citizen, 9 July 1924.It was innovations like this, along with every-day good value and courteous service, that made the store an Ottawa landmark. So, imagine the feelings when Poulin announced that he was retiring and the store would close. The Ottawa Citizen described it as the passing of an institution. “It did not seem right nor did it seem natural.” It was not as if the store was unprofitable, or there were no heirs to carry on the family name. Indeed, the Poulins’ four sons, Edmond, Gidias, Fabien and Clement, all worked in the family firm. The closure also meant that almost three hundred employees lost their jobs. At a farewell dinner dance held for his workers a few days after the store’s shut its doors for good, Poulin said that his employees would be able to find new careers if they did their best.

Poulin’s Sale, Ottawa Citizen, 9 July 1924.It was innovations like this, along with every-day good value and courteous service, that made the store an Ottawa landmark. So, imagine the feelings when Poulin announced that he was retiring and the store would close. The Ottawa Citizen described it as the passing of an institution. “It did not seem right nor did it seem natural.” It was not as if the store was unprofitable, or there were no heirs to carry on the family name. Indeed, the Poulins’ four sons, Edmond, Gidias, Fabien and Clement, all worked in the family firm. The closure also meant that almost three hundred employees lost their jobs. At a farewell dinner dance held for his workers a few days after the store’s shut its doors for good, Poulin said that his employees would be able to find new careers if they did their best.

If the rationale for the closure appears somewhat mystifying, Poulin’s timing was impeccable. Less than nine months after the store went out of business, the Great Depression began. The Schulte-United Corporation, which had moved into the former premises of Poulin’s department store, failed two years later, a casualty of the economic catastrophe.

Closing out sale, Ottawa Citizen, 30 January 1929.

Closing out sale, Ottawa Citizen, 30 January 1929.

Another person who had impeccable timing was Walter P. Zeller of Kitchener, Ontario. In 1928, he had sold his small chain of Zeller’s department stores located mostly in southern Ontario to the Schulte-United Corporation which wanted to expand into Canada. When Schulte-United failed three years later, Walter Zeller bought the Canadian wing of the operations. These comprised his original Zeller’s stores and ten other outlets that Schulte-United had established in the interim, including the former Poulin’s department store location on Sparks Street.

Zeller’s became a fixture on Spark Street for more than seventy years. The very profitable chain of bargain stores was bought by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1978. Growing to roughly 350 stores by the year 2000, the Zeller’s chain began to lose ground to competitors. Profitability declined. In 2011, the U.S. department store chain Target bought the leases of most Zellers stores for $1.825 billion in its ill-fated effort to break into the Canadian retail market. It promised to run them under the Zeller’s brand for a “period of time.” The larger Zeller’s branches were eventually remodelled and converted into Target outlets. Smaller ones, like the elderly store on Spark Street, did not fit the Target style. It closed its doors in 2013. Two years later, Target closed all of its 133 Canadian stores after a disastrous foray into Canada.

The distinctive building once owned by L. N. Poulin was almost demolished in the early 1980s as part of a high-rise development plan. Notwithstanding a demolition permit granted by Ottawa’s City Council, the building was saved at the last minute, in part by a campaign orchestrated by Heritage Ottawa. It was sympathetically renovated by its then owners, the Hudson Bay Company. Consistent with its long heritage as a discount retail store, the edifice that was once Poulin’s Department Store, and later Zeller’s, now houses a Winners outlet.

As for the Poulins, after their retirement, the couple moved to a home at cottage community of Britannia. Louis Napoleon Poulin stayed active in Ottawa’s commercial life as a director of the electric and gas companies. He died at the age of 85 in 1941. His wife, Mary Poulin, died in 1949.

Sources:

Heritage Ottawa, 2017. Poulin’s Dry Good Store| Zellers Department Store, https://heritageottawa.org/50years/poulins-dry-goods-zellers-department-store.

Ottawa Citizen, 1904. “Thousands of Dollars in Cash Refunded to Our Customers,” 11 July.

——————, 1904. “Your Money Back,” 2 September.

——————-, 1923. “Rebuilding of L.N. Poulin, Limited, Store To Add Another Chapter To Fascinating Story of Expansion Of An Ottawa Firm,” 19 June.

——————, 1928. “L.N. Poulin Is Retiring After Splendid Career,” 29 December.

——————, 1929. “Schulte-United Will Have a Fine Store in Capital,” 2 March.

——————, 1931. “Walter P. Zeller Heads Zellers Ltd, Formerly Schulte-United,” 7 November.

—————–, 1941. “Late L. N. Poulin, Noted Figure In Commercial Life,” 9 July.

Ottawa Journal, 1890. “No Bankrupt Stock,” 3 April.

——————-, 1924. “Mr. L.N. Poulin Host to His Employes (sic),” 10 January.

——————-, 1928. “Retiring after Forty Years of Business Here,” 29 December.

——————-, 1939. “7,000 Members of Poulin Families Join in Unique Celebration,” 19 August.

——————-, 1949. ‘Mrs. L.N. Poulin Dies,” 4 June.

Reuters, 2011. Target to enter Canada with Zellers deal, own plans, 13 January, https://www.reuters.com/article/target-canada/update-2-target-to-enter-canada-with-zellers-deal-own-plans-idUSN1326316220110113.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

James Powell: The Assassination of D’Arcy McGee

Our guest speaker for May 12, 2021 was James Powell, who is a long-time member of the Ottawa Historical Society, and a director on the HSO board.

For his presentation James spoke about one of the most tragic heroes in Canada’s history. Thomas D’Arcy McGee was murdered near his Sparks Street apartment on a chilly April evening in 1868. James talked about McGee’s early life in Ireland and his brief stay in the United States. While in the US he visited Canada, and it was here that McGee felt Ireland’s poor could find opportunities unavailable at home. Feeling that union of the French and English cultures would cultivate equality for all people, he promoted a greater Canada, thus becoming a Father of Confederation in the two years prior to his murder. It’s sad to think that a man who saw so much promise in Canada would be one of the few in this country’s history to be the target of a political assassination.

James also told the story of the man put on trial for McGee’s murder, and gave us an account of the suspicion surrounding Patrick Whalen’s conviction and execution.

You can watch the full presentation on McGee via our YouTube channel.

The Assassination of D'Arcy McGee

At our May 12th 2021 meeting, James Powell, HSO director and author of the popular blog "Today in Ottawa's History", took the audience back in time to the assassination of Thomas D'Arcy McGee, one of the Fathers of Canadian Confederation.

Ottawa's Greatest Store

6 September 1870

Sparks Street used to be the beating heart of Ottawa commerce, home to several major local department stores that had their roots in the late nineteenth century. These included L. N. Poulin’s Dry Goods store, R.J. Devlin & Company, Murphy-Gamble, and Bryson, Graham Ltd. One by one they disappeared into history. Most were bought out by larger chain stores before they too succumbed as shoppers flocked to exciting new suburban shopping centres with ample parking facilities that were closer to where people lived. But back during the early twentieth century when Sparks Street was at its zenith, the place to shop was Bryson, Graham Ltd, then known as “Ottawa’s Greatest Store.”

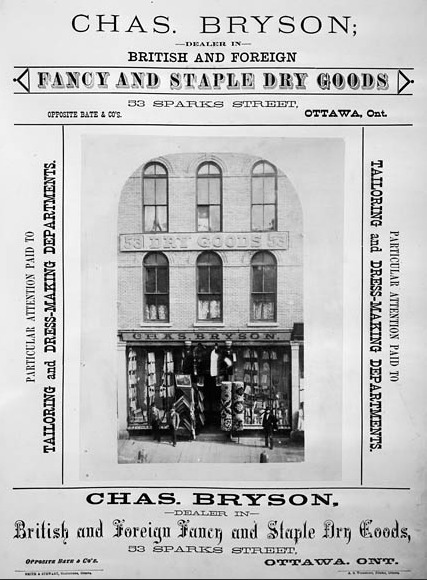

Charles Bryson’s Dry Goods Store, 53 Sparks Street, 1875, William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, PA-002237.It opened for business on 6 September 1870 as Patterson & Bryson at 53 Sparks Street on the south side of the Street (later renumbered as 110 Sparks Street). The firm was named after its two principals, Joseph H. Patterson and Charles B. Bryson. Initially, there wasn’t much going for the modest dry-goods business. With the main commercial streets in Ottawa at that time being Rideau, Sussex and Wellington, the store had an unpromising location. Business was tough during those early years. Indeed, in 1873, the partnership ended, with Patterson decamping to New York City to establish a dry goods business there. Bryson, a country boy from Richmond who had come to Ottawa in 1864 and learnt the dry-good business working at the firm T. Hunt & Sons, soldiered on alone. The split-up appeared to have been relatively amicable, or at least any hard feelings healed over time. On the firm’s silver anniversary in 1895, Patterson sent Bryson from New York a souvenir of their first day in business. Concealed inside twenty-five nested envelopes was the first 5-cent piece the store took in. On one side was engraved “P & B” with “6th Sept., 1870” inscribed on the other.

Charles Bryson’s Dry Goods Store, 53 Sparks Street, 1875, William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, PA-002237.It opened for business on 6 September 1870 as Patterson & Bryson at 53 Sparks Street on the south side of the Street (later renumbered as 110 Sparks Street). The firm was named after its two principals, Joseph H. Patterson and Charles B. Bryson. Initially, there wasn’t much going for the modest dry-goods business. With the main commercial streets in Ottawa at that time being Rideau, Sussex and Wellington, the store had an unpromising location. Business was tough during those early years. Indeed, in 1873, the partnership ended, with Patterson decamping to New York City to establish a dry goods business there. Bryson, a country boy from Richmond who had come to Ottawa in 1864 and learnt the dry-good business working at the firm T. Hunt & Sons, soldiered on alone. The split-up appeared to have been relatively amicable, or at least any hard feelings healed over time. On the firm’s silver anniversary in 1895, Patterson sent Bryson from New York a souvenir of their first day in business. Concealed inside twenty-five nested envelopes was the first 5-cent piece the store took in. On one side was engraved “P & B” with “6th Sept., 1870” inscribed on the other.

Things began to pick up in the 1880s after Bryson welcomed Frederick Graham into the business which by this point had moved to 152 Sparks Street. Like his colleague, Graham was a country boy. He had come to Ottawa to sell agricultural equipment for William Arnold on Wellington Street. Dissatisfied with his career choice, he joined Bryson in 1880 and very quickly proved his worth. After only a year, he was offered a piece of the business and became a junior partner. Bryson, Graham & Company was born. It was a partnership that was to last close to fifty years. Bryson took charge of the management of the company while Graham took responsibility for buying. In 1882, Graham became part of the family as well, marrying Miss Margaret Bryson, Charles Bryson’s sister.

During the early 1880s, the duo introduced a radical innovation to Ottawa—“One Price for All.” Hitherto, Ottawa residents haggled with merchants for all their purchases, a process that wasted valuable time and typically left somebody dissatisfied. At the same time, Bryson and Graham advertised “Maximum Value for the Money.” Initially, this novel approach to selling cost the partners business, but the general public quickly caught on.

In one possibly apocryphal story set sometime in the 1880s, ten lumbermen entered Bryson Graham to purchase their gear for the coming logging season. They picked out goods worth $650, a very large sum back in those days. The foreman offered to pay $600. The salesman refused. The foreman then asked if he would throw in a vest for each of the workers. Again, the salesman refused. A pair of braces? Again, the answer was no. The group left the store in a huff, repairing to “The Brunswick” for a drink. They later came back, their leader indicating that they would pay the $650 if the salesman threw in a collar button for each of the men. Again, the salesman refused. When called over, Bryson backed up his salesman and explained the store’s pricing policy to the lumbermen. Giving up and paying the full amount, the foreman admitted that he had bet $10 that he could beat down the store. He added that “it was worth more than $10 to find there is one honest price store in Ottawa.”

The reputation of Bryson and Graham for integrity and straight dealing was the backbone of their company. Over the next fifty years, the company prospered mightily. In 1883, the company expanded eastward, leasing the adjoining store. In 1887, the firm added home furnishings when it acquired the stock and premises of Shouldbred & Company, followed by the acquisition of the stock of dress-goods and silks from Mr John Garland. In 1890, John Bryson, the brother of Charles opened a grocery store in the Bryson-Graham premises. This business was later formally consolidated into the family enterprise. This was a gutsy step. The grocery business in Ottawa had previously been an albatross for other department stores. In 1892, the firm bought the china and crockery business of Mr Sam Ashfield in the neighbouring store. Two years later, the company expanded yet again and acquired the entire block when it took over the corset business of yet another neighbour, Mrs Scott. On their silver anniversary in 1895, the firm built a factory extension to Queen Street.

To mark twenty-five years of progress and expansion, the store’s staff gave Charles Bryson a gold-mounted ebony cane. They also presented a testimonial to their boss reading “…under your control, we are happy to labour, and hope that our constant efforts and devotion to business will meet with your appreciation. With great pleasure do we take this opportunity to congratulate you on your past success, and to say that we are proud to see your business house classed amongst the most important and successful houses of the Dominion.”

Innovations and expansion continued during the store’s second twenty-five years. In 1898, Bryson, Graham & Company was the first in Ottawa to use the “comptometer,” the first successful, key-driven, calculating machine. It was used for adding and calculating work, sales checks, statements and invoicing. In 1909, the partnership was transformed into a limited liability company. Two years later, the company erected a large warehouse on Queen Street to store its extensive inventory.

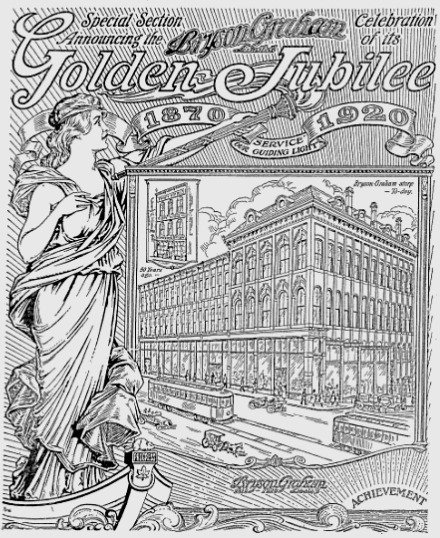

Cover to the Special Supplement in Celebration of Bryson-Graham’s Golden Anniversary, The Ottawa Citizen, 28 February 1920.In 1917, the long and successful partnership of Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham came to an end with the former’s death. Graham became the company’s president, with Mr James B. Bryson, the son of Charles, as vice-president. In 1920, the Ottawa Citizen newspaper celebrated the golden anniversary of the company with a supplement dedicated exclusively to the department store, its history, and its successes. The newspaper opined that the secret of the retailer’s success was the character of Charles Bryson—“his untiring efforts, his forceful personality and his integrity.” The paper also re-published his obituary that stated that Bryson “was a gentleman in business as in his private life; a kind employer, a devoted friend, a real Christian.” The newspaper stated that the many friends of “Ottawa’s Greatest Store” hoped that “the next fifty years will witness an expansion proportionate to that of those gone by.”

Cover to the Special Supplement in Celebration of Bryson-Graham’s Golden Anniversary, The Ottawa Citizen, 28 February 1920.In 1917, the long and successful partnership of Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham came to an end with the former’s death. Graham became the company’s president, with Mr James B. Bryson, the son of Charles, as vice-president. In 1920, the Ottawa Citizen newspaper celebrated the golden anniversary of the company with a supplement dedicated exclusively to the department store, its history, and its successes. The newspaper opined that the secret of the retailer’s success was the character of Charles Bryson—“his untiring efforts, his forceful personality and his integrity.” The paper also re-published his obituary that stated that Bryson “was a gentleman in business as in his private life; a kind employer, a devoted friend, a real Christian.” The newspaper stated that the many friends of “Ottawa’s Greatest Store” hoped that “the next fifty years will witness an expansion proportionate to that of those gone by.”

This wish was not granted. Three years later, in 1923, Frederick Graham died, and the venerable company on Sparks Street passed fully into the hands of the next generation of Brysons and Grahams. James Bryson took over as president and W.M. Graham stepped into the vice-president’s position. For a time, Bryson-Graham continued to do well, but its years of expansion were over. It had apparently transitioned into a comfortable middle age. While it continued to provide a wide range of quality goods to Ottawa customers at reasonable prices, the drive and determination of its founders were gone.

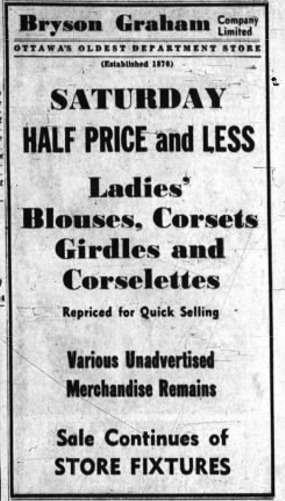

Bryson-Graham’s Last Advertisement, The Ottawa Journal, 17 April 1953Business suffered through the lean years of the Depression and World War II. By the late 1940s, the company was dowdy and old fashioned. In May 1950, Ormie A. Awrey, who had been vice-president and general manager of the firm for the previous eleven years acquired control of the business from the children of the late Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham, buying 85 per cent of the company for $1 million. He later bought the remaining shares. Awrey promised to carry on the traditions of the old firm, but the retailer continued to decline. Parts of the old building were rented out to other retailers, including Bata Shoes, Swears and Wells, and Dolcis. In February 1953, he sold the Bryson-Graham block in February 1953 to J. B. and Archie Dover of Dover’s Ltd for only $310,000. After holding a clearance sale of its stock and fittings, Bryson-Graham, now billed as “Ottawa’s Oldest Department Store,” closed for good on 18 April 1953, ending an 83-year presence on Sparks Street.

Bryson-Graham’s Last Advertisement, The Ottawa Journal, 17 April 1953Business suffered through the lean years of the Depression and World War II. By the late 1940s, the company was dowdy and old fashioned. In May 1950, Ormie A. Awrey, who had been vice-president and general manager of the firm for the previous eleven years acquired control of the business from the children of the late Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham, buying 85 per cent of the company for $1 million. He later bought the remaining shares. Awrey promised to carry on the traditions of the old firm, but the retailer continued to decline. Parts of the old building were rented out to other retailers, including Bata Shoes, Swears and Wells, and Dolcis. In February 1953, he sold the Bryson-Graham block in February 1953 to J. B. and Archie Dover of Dover’s Ltd for only $310,000. After holding a clearance sale of its stock and fittings, Bryson-Graham, now billed as “Ottawa’s Oldest Department Store,” closed for good on 18 April 1953, ending an 83-year presence on Sparks Street.

The Bryson-Graham building today, corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets, July 2017, Nicolle Powell

The Bryson-Graham building today, corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets, July 2017, Nicolle Powell

Today, the Bryson-Graham building at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets still stands. The ground floor is occupied by Nate’s Delicatessen.

Sources:

Elder, Ken, 2009. Bryson, Graham & Co., Ottawa Canada, http://www.eeldersite.com/Bryson-_Graham_-_Co.pdf.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1920. “Bryson-Graham Ltd Celebrates Its Golden Jubilee, 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Silver Anniversary of Store,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Character of Founder Largely Responsible For Store’s Success,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Battery of Comptometers Used in Bryson-Graham’s Stores,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Hard Work One Secret Of The Success Won By Messrs. Bryson-Graham,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “One-Price Policy Was Introduced In Ottawa By Bryson-Graham Co.” 28 February.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1895. “A Five Cents With A History,” 10 September.

————————–, 1935. “The Shops of the Capital, What they Were and Are,” 10 December.

————————–, 1950. “O.A. Awrey Acquires Control of Bryson Graham Ltd,” 5 May.

————————–, 1953. “Dovers Buy Bryson Blok,” 12 February.

————————–, 1953. “$10,000, Bryson-Graham Sale Heads May Property Deals,” 4 July.

Urbsite, 2012, Sparks Street Department Stores: Bryson Graham and Company, http://urbsite.blogspot.ca/2012/10/sparks-department-stores-bryson-graham.html.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

A Walk Down Sparks Street

20 May 1960

By the end of the 1950s, Sparks Street, Ottawa’s premier shopping district, home to major department stores, such as Murphy-Gamble, Morgan’s, and Woolworth’s, as well as jewellery boutiques, restaurants, and banks, was in decline. Shop fronts were starting to look shabby and dated. Competition from newfangled suburban shopping centres with lots of free parking was taking its toll. But the removal of the last street cars in May 1959 offered the street’s merchants the opportunity to buck the trend. Forming the Sparks Street Development Association, their solution was a pedestrian mall, an idea first suggested years earlier by Jacques Greber, the hyperactive French urban design consultant to the federal government charged with beautifying the city. Business owners hoped that a mall would boost customer traffic and commerce.

Overcoming the initial reluctance of City Hall, and opposition from Ottawa’s fire chief who was concerned about access in the event of fire, a temporary pedestrian mall, designed by Walter Balharrie, was officially opened by Mayor George Nelms on Friday, 20 May 1960. To add a note of glamour, the first Miss Dominion of Canada, “pretty Eileen Butter” of Ancaster, Ontario shared the podium with city and mall dignitaries. The street had actually been closed to vehicular traffic the previous Saturday evening so that workmen could paint patterns on the repaved roadway; install fifty potted trees, put in yellow, moulded, fibreglass benches, erect canopies, and install temporary flower beds. The National Gallery of Canada also loaned the mall a statue by prominent sculptor, Louis Archambeault, titled “Iron Bird.” Another Mall attraction was the introduction of outdoor cafés.

The Mall was well received by the general public. Immediately prior to its opening, the Ottawa Citizen enthused that “the public is becoming as proud of Sparks Street as a housewife is of her newly-washed sparkling windows” and that the “promenade will finish the job,” making the street a “place to dream in as well as to shop.” A New York expert lauded the Mall saying that it was the best planned and most well conceived of the several malls he had studied. He also opined that it would be a “great stimulant” to the local economy and would revitalize the city.

Sparks Street was reopened to traffic in early September 1960. But with the mall experiment deemed a success, a fact confirmed by a survey which indicated that supporters vastly outnumbered opponents, the temporary mall returned the following six summers. It became a permanent feature of the Ottawa cityscape in 1967, Canada’s centennial year. That year, the Sparks Street Mall, the first permanent pedestrian mall in North America, was made resplendent with fountains, sculptures, trees, plants, kiosks and canopies at a cost of $636,000. With the Canadian Guards Band striking up “God Save the Queen,” the new permanent Mall was officially opened on 28 June by Mayor Don Reid. Unfortunately, technical glitches meant that only one of the three fountains on the Mall was operational, and there was no sign of the planned rock garden. Proposed infra-red heating elements to be located under the canopies to keep pedestrians warm in winter were also not installed owning to cost considerations.

Although the establishment of the Mall may have slowed the decline of Sparks Street as a commercial and shopping district, urban blight continued. One by one, the major department stores closed their doors. The opening in 1983 of the downtown Rideau Centre, a major indoor shopping centre with ample parking, provided a major blow to Mall fortunes. Sparks Street retail sales plunged, as tourists and residents alike took their business to the Centre’s modern shopping facilities located in close proximity to the Byward Market’s many restaurants and nightclubs. Stalwarts, such as Birks Jewellers, also decamped to the Rideau Centre, leaving the Mall’s shopping façade snaggle-toothed.

In an effort to rejuvenate the Mall, governments and area merchants spent $5.5 million in 1986 to perk up things. Granite sidewalks, traditional lamp standards, and pavilions housing pay phones and mall directories were installed. The remodelling was not well received. The pavilions were bulky and obstructed the view of the Mall’s distinctive architecture. One heritage expert called them “gimmicky.” The improvements also did not address the Mall’s comparative disadvantages, including inadequate parking facilities and the lack of major anchor stores. It continued to be eclipsed by the Rideau Centre where people could shop in comfort during Ottawa’s cold winter months, and by suburban shopping centres which were conveniently located to where people lived. Street merchants also complained that their landlord—the federal government—which had expropriated many of the buildings on Spark Street owing to their proximity to Parliament Hill and their historic nature, was unresponsive to their needs and slow to act.

The decline of Sparks Street continued through the 1990s and 2000s. Shops continued to close. Much of an entire block of shops on the south side of the street between Bank Street and O’Connor Street was bulldozed in 2003 to make way for the CBC Ottawa Broadcast Centre. While care was taken to ensure that the Spark Street side of the new Centre was consistent with its low-rise neighbours, the new building did little to enhance Mall shopping. Moreover, with its principal entrance on Queen Street, pedestrian traffic declined. Extensive renovations by the federal government to the former Metropolitan Life building (now the Wellington building), as well as to the historic Beaux Arts former Bank of Montreal building has kept much of Sparks Street a building site for years. Now that the Bank of Canada headquarters at the western end of Sparks Street is under renovation, it will remain that way until at least 2017. As a final insult, in 2013, Zellers and Smithbooks, street features for decades, closed, leaving much of the Mall a shopping wasteland.

Today, the Mall is a shadow of its former self. Although its outdoor cafés, including a new microbrewery and restaurant at 240 Sparks, provide some life during the summer months, as do special events, such as the annual Buskers’ Festival or Ribs’ Fest, there is little shopping to attract people, residents or tourists, the rest of the year. Hopes for an urban renewal now centre on the possible construction of a boutique hotel and condominiums on the Mall.

Sources:

Rubenstein, H. 1992. Pedestrian Malls, Streetscapes and Urban Spaces, John Wiley & Sons Inc.

The Globe and Mail, 1960. “Mall and Tulips Open Ottawa Tourist Season,” 20 May.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1960. “Prospects for Spring,” 7 May.

—————–, 1960. “The Sparks Street Mall,” 9 May.

—————–, 1960. “Official Opening of the Sparks Street Mall, 20 May.

—————–, 1961. “The Sparks Street Mall,” 1 February.

—————–, 1961. “Providing for Fire Safety on the Sparks Street Mall,” 13 March.

—————–, 1961. “The Sparks Street Mall,” 1 September.

—————–, 1967. “Pedestrians take Over Mall,” 25 June.

—————-, 1969. “Sparks Street Mall, Chronology of Events,” 2 June.

—————-, 1986. “$5.5 million Facelift for Sparks St Approved,” 29 October.

—————-, 1987. “The Mall Needs More than a New Suit,” 13 January.

Urbsite, 2010. Sparks Street Mall Turns Fifty.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Origins of Street Names

January 1820

Considering how many people in Ottawa are new to the city, it seemed reasonable to do a little research and find out who, or what, some of the oldest Ottawa streets are named after. Many persons who contributed to the foundation and growth of our City are not well known, and I understand both City staff and the Historical Society of Ottawa have developed tentative plans to make early Bytowners or Ottawans better known. This is a project deserving support! No article of this size can hope to do much more than scratch the surface of this topic. So only a few streets are covered.

Much has been said and written about the proper use of Lebreton Flats which contained Lebreton Street. These were named after Charles LEBRETON (1779-1848) who was a native of Jersey and one of Nepean Township's earliest settlers. He came to our area from Newfoundland and served with distinction in the War of 1812. With a partner, he purchased Lebreton Flats in 1820 and, in 1826 got into a legal wrangle with Colonel By and the Governor General, Lord Dalhousie over the price he wanted for his land. He spent a good deal of money defending the legality of his land ownership against the government of the day He retained his land, but the Rideau Canal was built elsewhere probably because Dalhousie and By rather disliked him after the court battle. Was sour grapes involved in the location of the canal?

Nicholas SPARKS (1792-1862) for whom Sparks Street is named is much better known,. but the extent of his good works in Ottawa is less known Sparks came to Canada in 1816, from Ireland, to avoid religious strife. He married the widow of Philemon Wright Jr. in 1826. He owned a sawmill and vast timber rights in the area. In 1821, for the equivalent of $500 he purchased land that extended from what is now Wellington St. to Laurier Avenue West and from Waller Street to Bronson Avenue. He sold part of his land to construct the Rideau Canal, but, because of the price he asked, another 96 acres were expropriated much to his chagrin!

Perhaps wishing to avoid religious strife in Canada, he donated land for churches to both the Anglicans and the Presbyterians. Sparks went on to serve for many years in local government. Sparks named a street on his land after a friend, Daniel O' CONNOR, who became Treasurer of the Dalhousie District (later Ottawa-Carleton) and another after his son-in-law, James SLATER Slater Street was first named Waugh Street, after a local merchant Caldwell Waugh., James Slater came to Canada about 1830, married Sparks' daughter in 1847 and went on to be, successively, Provincial Land surveyor, Superintendent of the Rideau Canal and Chairman of the Ottawa School Board.

Robert BELL (1821-1873) was a promoter of railway construction, a land surveyor and eventually, a journalist. He bought the Bytown Packet in 1849 and two years later changed the name to the Citizen, He sold the paper in 1865 to I. B. Taylor. One of the people from whom he bought the paper, Henry J. FRIEL (1823-1869) served as Mayor of Bytown in 1854 and Mayor of Ottawa in 1857, 1863, 1868 and finally, 1869 Pictures of both Bell and Friel are available at the City Archives.

More streets named after prominent Ottawa residents

In Lower Town, Bruyere Street is named after Mother Elizabeth BRUYERE (1818-1876) the founder of the Grey nuns and the Ottawa Hospital (1845) She also established an orphanage, a hospice and an asylum for destitute women. GUIGUES Street is named after Monsignor Joseph-Eugene—Bruno Guigues (1805-1874), Ottawa's first Roman Catholic Bishop. He founded what became the University of Ottawa on land donated by Louis BESSERER.

Further west, BRONSON Avenue was named after Erskine Henry Bronson, a prominent businessman, whose father Henry Bronson had founded a local lumbering firm. Speaking of lumbering, who else could BOOTH Street be named after other than J. R. Booth “the Ottawa Valley Lumber King”.

These are only a few of the origins of Ottawa street names. The City of Ottawa Archives is working on identifying many more.

Cliff Scott, an Ottawa resident since 1954 and a former history lecturer at the University of Ottawa (UOttawa), he also served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Public Service of Canada.

Since 1992, he has been active in the volunteer sector and has held executive positions with The Historical Society of Ottawa, the Friends of the Farm and the Council of Heritage Organizations in Ottawa. He also inaugurated the Historica Heritage Fair in Ottawa and still serves on its organizing committee.