The Inter-Provincial Bridge, a.k.a. The Royal Alexandra Bridge

12 December 1900

During much of the nineteenth century, only one bridge spanned the mighty Ottawa River linking the burgeoning community of Bytown, later known as Ottawa, with its sister town of Hull on the northern shore. Initially, this was the wooden Union Bridge which was completed in 1828 close to the Chaudière Falls. That bridge collapsed a few years later and was superseded by the Union Suspension Bridge in 1843. This bridge became the main thoroughfare linking Ontario and Quebec for the rest of the century. Condemned in 1919, it was replaced by the Chaudière Bridge which is still in operation today.

In 1880, the Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway Company built a railway bridge across the Ottawa River close to Lemieux Island. Initially called the Chaudière Railway Bridge, its name was later changed to the Prince of Wales Bridge in honour of the eldest son of Queen Victoria, the future King Edward VII. (When this name change occurred is uncertain but it was no later than 1887.) However, the Prince of Wales bridge did not carry pedestrian or carriage traffic, and was far removed from the city centre.

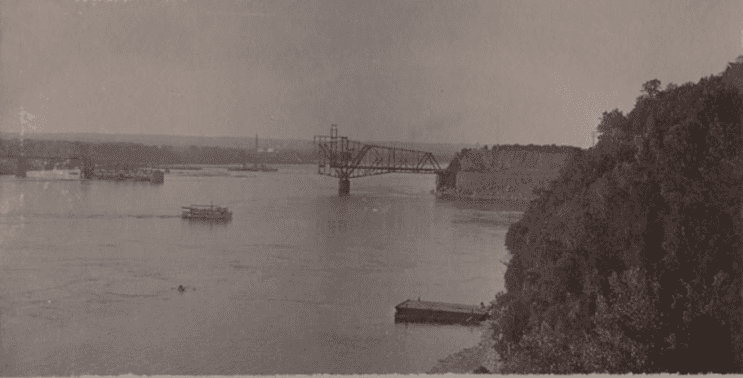

The Inter-provincial Bridge under construction, 1900, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4459589.

The Inter-provincial Bridge under construction, 1900, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4459589.

Discussion of a new interprovincial bridge to the east of the Union Suspension Bridge actually predated the construction of the Prince of Wales Bridge. In 1877, meetings were held at Ottawa’s City Hall on the construction of a railway and carriage road bridge linking Rockcliffe in Ontario with the small Quebec community of Waterloo on the north shore of the Ottawa. The plan was for the Ottawa & Toronto Railway Company to link its rails with the Montreal, Ottawa & Occidental Railway by way of the bridge. There were also plans to build a central depot near Elgin Street linking downtown Ottawa with the Rockcliffe bridge. But the scheme failed to gain political traction with the provincial or federal governments. Bridge supporters had hoped that governments would provide much of the $380,000 needed to fund construction.

In 1883, Sir Charles Tupper, the then Minister of Railways and Canals, put the kibosh on the proposal on the grounds that the road to the bridge had not been completed, and that the Quebec and Ontario governments had not provided any funding. Four years later, a similar proposal was mooted, with a bridge over the Ottawa at Rockland, Ontario. Supporters viewed it as an ideal Jubilee project to celebrate Queen Victoria’s golden anniversary on the throne with the suggestion that it be called the “Victoria Inter-provincial Bridge.” The idea went nowhere.

In 1890, the Pontiac & Pacific Junction Railway (P.P.J.R.) and the related Gatineau Valley Railway Company came up with a new proposal for an interprovincial bridge to link Ottawa to Hull at Nepean Point with a central depot to be built at the Rideau Canal. The price tag was estimated at roughly $800,000 including the cost of building the approaches to the bridge on both shores.

This idea was warmly greeted by important Ottawa citizens and groups, including former mayor Francis McDougal. Ottawa’s City Council, the Ottawa Board of Trade, and the Trades and Labour Council. Other communities in eastern Ontario and western Quebec later came out in support of the proposal. In 1894, the City of Ottawa taxpayers voted in favour of By-law 1,458 to give a “bonus” of $150,000 to the P.P.J.R. upon the completion of a bridge for railway, carriage and pedestrian traffic. Instead of cash, the City would hand over 30-year debentures paying an interest rate of 4 per cent. There were conditions, however. Most importantly, the inter-provincial bridge would have to be completed by July 1897.

Applications for grants also went to the Ontario, Quebec, and Dominion governments. High-powered deputations of railway and municipal officials lobbied members of legislatures. Ontario came through with $50,000 in April 1895, only a fraction of what was sought. The Quebec government chose not to provide any funds. After much delay, the Dominion government provided $212,000. In the meantime, the City of Ottawa twice extended its deadline for the railway to qualify for its $150,000 bonus.

With financing, both private and public, adequately secured, and the plans approved by the Department of Railways and Canals, work finally commenced in February 1898. The bridge would carry a single-track railway line in the centre with two carriage roads and sidewalks for pedestrians.

Including its approaches, the bridge is 2,685 feet long with a clear span of 1,050 feet, the fourth longest bridge of this type in the world at that time. Five piers were constructed to support the structure with the deepest pier located in 70 feet of water. Messrs. McNaughton & Broder were awarded the contract for building the piers. The Dominion Bridge Company of Montreal won the contract for the bridge’s superstructure. The bridge was designed by a team of Canadian engineers led by G.C. Dunn.

Bridge engineers faced some difficult challenges in building the piers owing to sunken logs and sawdust littering the river bed. Before finding bedrock for pier two, workers had to go through eight feet of drowned boards and timbers. At pier three, sawdust thirty feet deep had to be removed using a “clam-shell” dredge. While there were federal laws against fouling waterways, the law apparently did not apply to the Ottawa River—a testament to the political strength of the Ottawa Valley timber barons.

After clearing away the debris at pier two, workers discovered that the bedrock was sharply sloped. To level the area, they blasted the stone using dynamite placed in holes and attached by wires to an electric battery on Nepean Point. Reportedly, the blasts were imperceptible until smoke and bubbles came to the surface of the river. Caissons, built of twelve-inch thick wooden boards, were installed around the work sites. Into them, workers poured cement to form the base of the piers. Ten thousand barrels of cement were used in building the five piers. Stone for the masonry work came from quarries in Rockland and Eganville.

The Ottawa Approach to the Inter-provincial bridge, Nepean Point,

The Ottawa Approach to the Inter-provincial bridge, Nepean Point,

William Topley/Library and Archives Canada, PA-009430.

Another challenge that workers faced was building the approaches to the new bridge, especially on the Ontario side of the River. Labourers carved out thirty-five feet from the face of the cliff at Nepean Point to form the roadbed. A considerable portion of Major’s Hill Park was also sacrificed to make the entrance into downtown Ottawa. As well, the stone abutments of Sappers’ Bridge were pierced to provide an entry for trains into the new central train station located beside the Canal. The stone abutments were replaced by iron and steel supports that allowed for room for the trains.

Given the engineering challenges, the extensive excavation work, and delays in obtaining needed supplies, the construction of the bridge took much longer than expected. There was also the occasional labour action. In January 1900, stone cutters downed tools when their wages were cut from $3 per day prevailing during the previous summer, to $2.50 per day at the beginning of December to only $2 per day.

Because of these delays, work was hurried to ensure that conditions for the Ottawa bonus were met. Despite the haste, however, there seems to have been few accidents, and the ones that did occur were relatively minor.

Whether or not the P.P.J.R. had met all the conditions to qualify for the City of Ottawa bonus of $150,000 in debentures became contentious. Some aldermen as well as the City’s engineer maintained that the railway had failed to meet an intermediate condition of spending a minimum of $50,000 on the construction by the middle of March 1898. Consequently, they wanted to withhold the bonus. The railway said otherwise and threatened to sue. In the event, the bonus was eventually paid. There was also controversy over the nature of the bonus. Since the time the bonus was originally agreed, interest rates had fallen from 4 per cent to 3 ½ per cent. This implied that market value of the debentures had increased significantly. Instead of $150,000, the bonus was effectively worth roughly $162,000. There were unfavourable comments in the press about the City’s financial acumen in promising to give the railway company marketable debentures rather than cash.

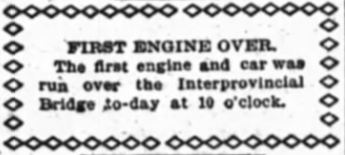

The small announcement of the first bridge transit,

The small announcement of the first bridge transit,

12 December 1900. The Ottawa Evening Journal.

Another hiccup along the way was a proposal by a consortium of investors led by the Hull & Alymer Electric Railway to build another bridge across the Ottawa River, with the Ottawa end coming out at roughly Bank Street. The idea was to provide electric streetcar service from Hull to the Ottawa shore of the Ottawa River. The proposal was warmly greeted by both the Hull and Ottawa city councils as well as the Ottawa Retail Merchants Association, especially as the backers of the bridge were not seeking public money. However, there was strong opposition from the Inter-provincial Bridge Company, which was owned by the P.P.J.R., that argued that the new bridge would divert business away from its bridge. As well, the Ottawa Electric Railway owned by Thomas Ahearn, complained that should the Hull streetcar company provide service to Ottawa, even just to the Ontario shore of the Ottawa River, its monopoly rights would be infringed. The proposed Bank Street bridge failed to get a charter from the federal government despite several attempts.

By December 1899, the Dominion Bridge Company was ready to start building the building’s superstructure with six barge loads of steel on site. Work moved rapidly from that point. By October 1900, Ontario and Quebec were connected and work was underway in building the roadbed. Venturesome youth were spotted making the dangerous journey across the iron work from one side of the bridge to the other. On 12 December 1900, the first test train made its way over the new bridge without mishap and without fanfare. Only a small announcement in the Journal newspaper celebrated the event. A month later, Chief William F. Powell of the Ottawa Police Force and his wife were the first to drive their carriage over the bridge. They were initially stopped by a bridge guard, but were subsequently allowed to proceed when the Chief identified himself. In mid-February 1901, the inter-provincial bridge was checked out first by Dominion inspectors and subsequently by the City of Ottawa’s inspector and aldermen. Having received a positive assessment, the bridge opened to the general public for the first time at noon, 5 March 1901.

More test trains ran over the bridge, including one consisting of four heavy locomotives drawing several cars bearing heavy loads of stone and steel. Weighing more than 400 tons, far beyond the weight of a usual train, the idea was to test the endurance of the bridge. Not even the slightest tremor was felt.

Another less felicitous milestone occurred on 14 April 1901 when the bridge experienced its first accident. An approaching train spooked a horse pulling a rig occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Lahaise, the owners of a furniture store on Rideau street. The horse galloped across the bridge towards Hull and crashed into a carriage driven by Mr. and Mrs. James Cudd who were out for a pleasure drive. Mr. and Mrs. Lahaise suffered shock and bruises when they jumped from their rig to safety. Pedestrians were also sent scurrying to safety to get out of the horse’s path. While the Lahaise carriage suffered no damage, the Cudds’ buggy sustained a badly twisted wheel and back axle.

The cross-bridge train service from the Hull Station to Ottawa’s new Central Station was officially opened on 22 April 1901; scheduled service had in fact commenced four days earlier. For the big event, both bridge and train were decorated with flags and bunting. On board, were city dignitaries and railway officials. Mr. John Lauzon was the first official paying passenger. Souvenir badges were presented to all on board that inaugural seven-minute journey. Conductor Hoolihan was in charge, with engineer Mr. W. McFall. As the train rolled onto the bridge, Mr. Noe Valiquette, the proprietor of the Cottage Hotel, broke a bottle of wine on the locomotive. Huge crowds of spectators standing on the Dufferin Bridge, greeted the arrival of the train into Ottawa.

Alexandra Bridge today, by SimonP, Wikipedia.

Alexandra Bridge today, by SimonP, Wikipedia.

In August 1901, Ottawa’s Mayor William Morris suggested that the new inter-provincial bridge be called the Royal Alexandra Bridge in honour of the wife of King Edward VII. The bridge’s railway owners readily agreed with the suggestion. The bridge’s “christening” was planned for the following month when Their Royal Highnesses, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, (the future King George V and Queen Mary), came to Ottawa for the unveiling of a monument to Queen Victoria on Parliament Hill. It was proposed that the Duchess would press a button to illuminate the bridge. However, while the bridge was decked out in electric lights, which spelled out the words “Royal Alexandra Bridge” in twelve-foot letters on its side as part of the illumination of the City done specially for the Royal Visit, contemporary newspaper accounts don’t mention whether the Duchess turned the lights on. However, the royal couple did cross the bridge by carriage to visit Hull which was still recovering from the great fire of 1900.

When the Central Station, called Union Station from 1920, was closed for train traffic in 1966, the train tracks on the Alexandra Bridge were removed and the bridge converted entirely to vehicular and pedestrian traffic. In 1995, the Canadian Society for Civil Engineering designated the bridge as a National Historical Civil Engineering Site.

Today, the venerable Alexandra Bridge, the oldest bridge in service across the Ottawa River, is approaching the end of its life. Owned by the federal government, the decision has been made to replace the bridge with construction on its replacement to be completed by 2032.

Sources:

CSCE, 2022. Alexandra Bridge, Ottawa Ontario — Hull, Quebec.

National Capital Commission, 2021. Alexandra Bridge Replacement, December.

Montreal Gazette, 1995. “From The Queen City,” 11 April.

Ottawa Citizen, 1877. “The Inter-Provincial Bridge Scheme, 13 November.

——————, 1877. “The Inter-Provincial Bridge,” 14 November.

—————–, 1883. “Dominion Parliament,” 18 May.

—————–, 1887. “Queen’s Jubilee – Bridge Over The Ottawa,” 23 March.

—————–, 1895. “The Inter-provincial Bridge,”31 January.

—————–, 1997. “New Bridge For The Ottawa,” 22 November.

—————–, 1898. “Everything Arranged,” 11 January.

—————–, 1898. “Work Starts In A Few Days,” 1 February.

—————–, 1898. “Work On The Big Bridge,” 7 February.

—————–, 1898. “The First Pier Started,” 8 February.

—————–, 1900. “Work On Sapper’s Bridge,” 28 February.

—————–, 1900. “The New Bridge,” 17 November.

—————–, 1901. “Bridge Was Inspected,” 18 February.

——————, 1901. “Begun Three Years Ago,” 5 March.

——————, 1901. “The First Runaway,” 15 April.

——————, 1901. “Stood The Test,” 20 April.

——————, 1901. “Formally Opened,” 23 April.

——————, 1901. “Alexandra Bridge,” 8 August.

——————, 1901. “Alexandra Bridge,” 26 August.

——————, 1901. “The Duchess of Cornwall and York,” 21 September

Ottawa Evening Journal, 1887. “Cold Water,” 5 February 1887.

—————————–, 1893. “By-Law No. —,” 6 December.

—————————–, 1894. “Nepean Point Bridge,” 16 June.

—————————–, 1898. “Bank Street Bridge Defeated,” 14 April.

—————————–, 1898. “A Scene Of Great Activity,” 6 June.

—————————–, 1898. “A Stupendous Undertaking,” 15 October.

—————————–, 1900. “Train Over The New Bridge,” 12 December.

—————————–, 1901. “First To Drive Across,” 15 January.

—————————–, 1901. “To Be Named Alexandra,” 15 August.

Woodard, Rick. 2019. “Alexandra Bridge could be replaced within 10 years,” Global News, 19 March.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Canal Basin: Going, Going, Gone

14 November 1927

Readers may be surprised to learn that the Rideau Canal of the twenty-first century is considerably different from the Rideau Canal of the nineteenth century. In the old days, the Canal was very much a gritty, working canal. While it had its share of pleasure boats that plied its length, commerce was its main function. At its Ottawa end, barges, pulled by horses and men along canal-side tow paths, were drawn to warehouses that stretched from the Plaza at Wellington Street to the Maria Street Bridge (the predecessor of the Laurier Avenue Bridge). Lumber, coal and other materials were piled high along its banks awaiting delivery. Consequently, the Rideau Canal was anything but a scenic port of entry into the nation’s capital. Later, railroads and train sheds replaced the warehouses on the eastern side when the Central Depot, the forerunner of Union Station (currently the Ottawa Conference Centre and soon to be the temporary home of the Senate), opened in 1896. While practical, this was not an aesthetic improvement.

The quality of the Canal’s water during the late nineteenth century was also considerably different than that of today. While we sometimes complain about the turbid nature of the water and the summertime weeds that choke stretches of the waterway and parts of Dow’s Lake, this is nothing compared to the complaints of residents of the 1880s. Then the Canal literally stank. The sewer that drained the southern portion of Wellington Ward, the neighbourhood located between Concession Street (Bronson Avenue) and Bank Street flowed into the Canal at Lewis Street. The smell was particularly bad in spring when the effluent that had entered the Canal through the winter thawed. Reportedly, the stench of festering sewage was overpowering. So bad were the conditions, the federal government forced the municipal authorities to fix things. After considerable delay, a proper sewer was constructed.

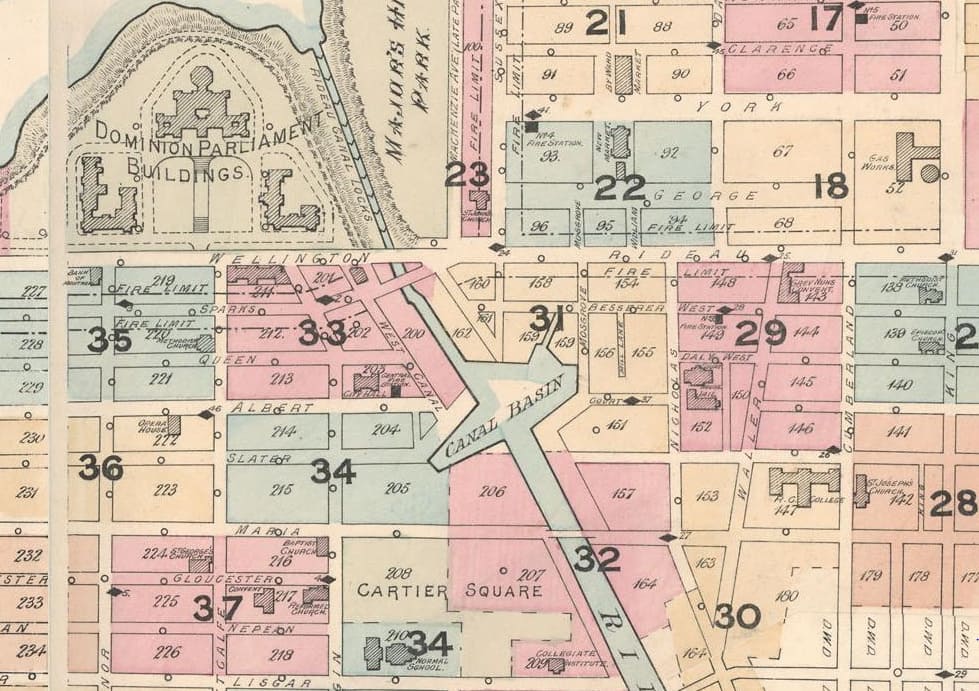

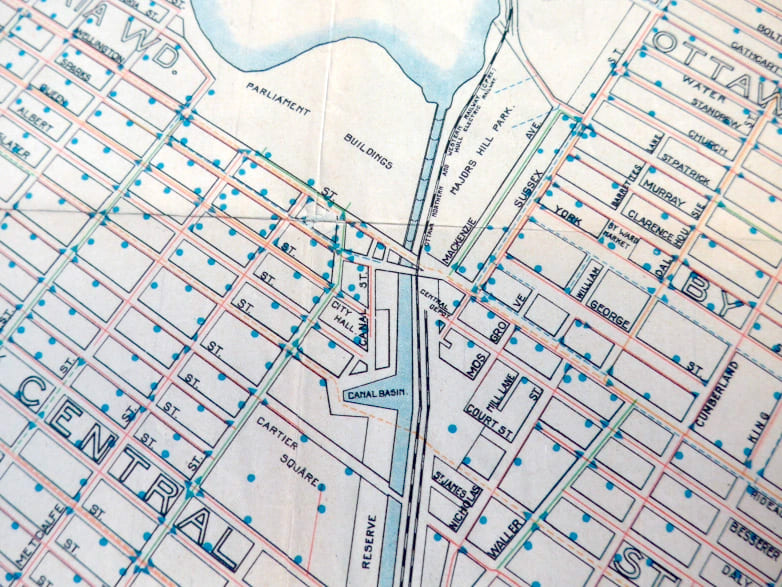

Detail of 1888 Map of Ottawa, City of Ottawa Archives. Note the Canal Basin. By now, only a rump of the By-Wash remained.The other not so delightful feature of the waterway was its flotsam and jetsam. Stray logs—a hazard to navigation—was the least of the problem. Prior to the first annual Central Canada Exhibition held in Ottawa in 1888, one concerned citizen pointed out the many nuisances to be found by boaters on the Canal. These included several carcasses of dead dogs floating in the Deep Cut (that portion of the Canal between Waverely Street and today’s city hall) and a bloated body of a horse bobbing in the water opposite the Exhibition grounds. The citizen also groused about the “vulgar habit” of people swimming in the Canal without “bathing tights.” He didn’t comment on the advisability of canal swimming given the horrific water quality.

Detail of 1888 Map of Ottawa, City of Ottawa Archives. Note the Canal Basin. By now, only a rump of the By-Wash remained.The other not so delightful feature of the waterway was its flotsam and jetsam. Stray logs—a hazard to navigation—was the least of the problem. Prior to the first annual Central Canada Exhibition held in Ottawa in 1888, one concerned citizen pointed out the many nuisances to be found by boaters on the Canal. These included several carcasses of dead dogs floating in the Deep Cut (that portion of the Canal between Waverely Street and today’s city hall) and a bloated body of a horse bobbing in the water opposite the Exhibition grounds. The citizen also groused about the “vulgar habit” of people swimming in the Canal without “bathing tights.” He didn’t comment on the advisability of canal swimming given the horrific water quality.

The physical geography of the Rideau Canal was also different back then. Patterson’s Creek was much longer in the nineteenth century than it is today; its western end became Central Park in the early twentieth century. There was also Neville’s Creek that flowed through today’s Golden Triangle neighbourhood and entered the Canal close to Lewis Street. The Creek, which was described as a cesspool in the 1880s, was filled in during the early twentieth century.

But the biggest difference was the existence of a large canal basin located roughly where the Shaw Centre and National Defence are today on the eastern side of the Canal and the National Arts Centre and Confederation Park are on the western side. This basin, which was lined with wooden docks, was used for mooring boats, turning barges, and picking up and delivering cargo and passengers.

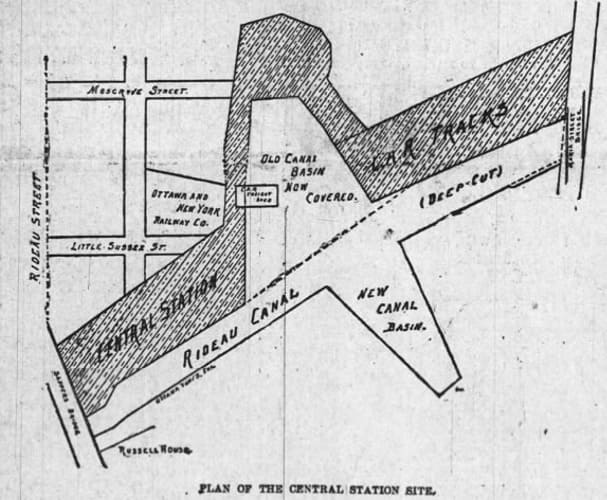

Diagram of the Rideau Canal and the covered eastern Canal Basin, 1897

Diagram of the Rideau Canal and the covered eastern Canal Basin, 1897

The Ottawa Evening Journal, 30 October 1897.Before the Canal was constructed, the canal basin was originally a beaver meadow from which a swamp extended as far west as today’s Bank Street. Following the Canal’s completion in 1832, which included digging out the basin, a small outlet or creek called the By-Wash extended from the north east side of the basin. It was used to drain excess water from the Canal. Controlled by a sluice gate, the By-Wash flowed down Mosgrove Street (now the location of the Rideau Centre), went through a culvert under Rideau Street, re-emerged above ground on the northern portion of Mosgrove Street, before heading down George Street, crossing Dalhousie Street on an angle to York Street, and then running along what is now King Edward Street to the Rideau River. In addition to controlling the Canal’s water level, the By-Wash was used by Lower Town residents for washing and fishing. In 1872, the City successfully petitioned the federal authorities who controlled the Rideau Canal to cover the By-Wash. It was converted into a sewer with only a small rump remaining close to the canal basin that was used as a dry dock.

Detail of Map of Ottawa, circa 1900, City of Ottawa Archives. Note that the eastern Canal Basin has disappeared.Big changes to the canal basin started during the last decade of the nineteenth century. John Rudolphus Booth, Ottawa’s lumber baron and owner of three railways, the Ottawa, Arnprior & Parry Sound Railway (the O.A. & P.S.), the Montreal & City of Ottawa Junction Railway, and the Coteau & Province Line Railway & Bridge Company (subsequently merged to form the Canadian Atlantic Railway–CAR), received permission from the Dominion government to bring trains into the heart of Ottawa. Hitherto, his railways provided service to the Bridge Street Station in LeBreton Flats and to the Elgin Street Station, both a fair distance from the city’s centre. In early March 1896, Booth, through his O.A. & P.S. Railway, acquired from the government a twenty-one year lease for the

Detail of Map of Ottawa, circa 1900, City of Ottawa Archives. Note that the eastern Canal Basin has disappeared.Big changes to the canal basin started during the last decade of the nineteenth century. John Rudolphus Booth, Ottawa’s lumber baron and owner of three railways, the Ottawa, Arnprior & Parry Sound Railway (the O.A. & P.S.), the Montreal & City of Ottawa Junction Railway, and the Coteau & Province Line Railway & Bridge Company (subsequently merged to form the Canadian Atlantic Railway–CAR), received permission from the Dominion government to bring trains into the heart of Ottawa. Hitherto, his railways provided service to the Bridge Street Station in LeBreton Flats and to the Elgin Street Station, both a fair distance from the city’s centre. In early March 1896, Booth, through his O.A. & P.S. Railway, acquired from the government a twenty-one year lease for the

east bank of the Rideau Canal from Sapper’s Bridge (roughly the location of today’s Plaza Bridge) to the beginning of the Deep Cut for $1,100 per year “for the purpose of a canal station and approaches thereto.” Lease-holders of properties between Theodore Street (today’s Laurier Avenue East) and the canal basin were told to vacate. After building a temporary Central Depot at the Maria Street Bridge on the Theodore Street side, Booth subsequently extended the line across the canal basin to a new temporary Central Station at the Military Stores building at Sappers’ Bridge.

Initially, the railway crossed the basin on trestles, leaving the basin underneath intact while Booth dredged the western side of the canal basin and built replacement docks—the quid pro quo with the government for removing the eastern basin’s docks. It seems that the government was reluctant to allow Booth to fill in the eastern portion of the basin until the western portion had been deepened, fearing that any unexpected rush of water might be larger than the locks could handle leading to flooding. By mid-March 1896, 75 men and 25-35 horses were hard at work excavating the site. The Central Depot at Sappers’ Bridge was completed in 1896, and was promptly the subject of dispute between Booth and his railway competitors who also wished to use a downtown station. There was rumours that if the Canadian Pacific Railway could not come to terms with Booth, it would build a railroad on the western side of the Canal with a terminus on the other side of Sappers’ Bridge across from the Central Station. Fortunately, with government prodding an accommodation was made. Initially covered over with planks, the western portion of the Canal Basin was subsequently filled in. A new Central Station, later renamed Union Station, opened in 1912.

Rideau Canal, circa 1911. The western Canal Basin is on the left. Union Station and the Château Laurier are under construction.

Rideau Canal, circa 1911. The western Canal Basin is on the left. Union Station and the Château Laurier are under construction.

Department of Mines and Technical Surveys, Library and Archives Canada, PA-023229.

If the eastern Canal Basin was sacrificed to the railway, the western Canal Basin was the victim of the automobile. This time, the Federal District Commission (FDC), the forerunner of the National Capital Commission, was responsible. Consistent with its plan to beautify the nation’s capital, the FDC in cooperation with the municipal authorities decided to extend the Driveway from the Drill Hall to Connaught Plaza (now Confederation Plaza) at a cost of $150,000. These funds also covered the construction of two connections with Slater Street, a subway at Laurier Avenue, new light standards, landscaping, and a new retaining wall for the Rideau Canal. Again, firms with warehouses at the Canal Basin, including the wholesale grocers L.N. Bate & Sons and the wholesale hardware merchant Thomas Birkett & Son, were forced to relocate. By the end of April 1927, workmen using steam shovels and teams of horses were hard at work filling in the western Canal Basin. Huge piles of earth were piled up near the Laurier Street Bridge ready to be shifted into the basin. On 14 November 1927, the last renovations to the Rideau Canal commenced with the construction of the new retaining wall from Connaught Plaza to the Laurier Street Bridge. With that, the old Canal Basin, which had served Ottawa for almost 100 years, vanished into history.

Sources:

Colin Churcher’s Railway Pages, 2017. The Railways of Ottawa.

Daily Citizen (The), 1895. “Central Station Site,” 1 August.

Evening Citizen (The), 1898. “The New Line.” 11 June.

Evening Journal (The), 1888.” The City Sewerage,” 19 April.

—————————, 1888, “The By-Law,” 27 April.

—————————, 1888. “Canal Nuisances,” 28 May.

—————————, 1895. “Notice to Quit,” 3 October.

—————————, 1895. “Now For The New Basin,” 9 November.

—————————, 1896. “Now For The Depot,” 4 February.

—————————, 1896. “Basin Widening Begun,” 4 March.

—————————, 1896. “Pushing It Ahead,” 11 November.

—————————, 1896. “For The New Station,” 23 May.

—————————, 1897, “Picked From Reporter’s Notes,” 20 October.

————————–, 1897, “Special C.P.R. Depot All Talk,’ 30 October.

————————–, 1898, “The Central Station,” 7 November.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1925. “History of Early Ottawa,” 10 October.

————————–, 1927, “Start Filling Basin Of Rideau Canal,” 26 April.

————————–, 1927. “Artist’s Conception of Park Scheme Proposed by The Prime Minister,” 11 June.

————————–, 1927, “The Railways And he Central Station,” 1 November.

————————–, 1934. “Understanding Shown In Letters Between King Ministry and Ottawa Concerning Beautification of City,” 6 January.

————————–, 1935. “Ottawa’s Beauty Developed On Broad Lines,” 10 December.

————————-, 1949. “Ottawa’s Vanished Water Traffic,” 15 September.

Ottawa, Past & Present, 2014. “Aerial View of the Rideau Canal 1927 and 2014,”.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Arrival of the Iron Horse

25 December 1854

An iconic image of the Industrial Revolution is the train, powering across the countryside, with clouds of smoke and steam billowing from its locomotive’s smokestack. Not only a new, rapid form of communication, the train embodied the scientific and technological discoveries of the age, the heavy industries needed to make and power it, and the innovative manufacturing techniques required to turn out the miles of iron rails on which it ran. Within twenty years of the inauguration of the world’s first steam-powered, interurban rail line between Liverpool and Manchester in 1830, Europe and the Americas were in the grip of a railway mania, similar to the “dot com” bubble of the 1990s. Hundreds of railway companies were formed; many went bust, though not before leaving behind a massive railway infrastructure legacy. The railway transformed the economies of the world, linking distant communities and opening new markets. In the Americas, the railway provided European settlers with access to virgin territory to exploit (and native communities to despoil), and, in the case of Canada, gave birth to a nation that spanned a continent.

The first Canadian railway was constructed in 1836 in Lower Canada, now Quebec. The Champlain and St Lawrence Railroad ran between La Prairie on the St Lawrence to St Jean on the Richelieu River, a navigable waterway that debouches into Lake Champlain. The railway cut hours off the long journey between Montreal and New York City. Railway building began in earnest in Canada following the Guarantee Act of 1849 under which the Province of Canada government offered cheap financing to companies building railways of at least 75 miles in length. Additional government financing was forthcoming after the 1852 Municipal Loan Act. In 1850 there was less than 110 kilometres of railroad laid down in Canada. Ten years later, there was more than 3,200 kilometres.

Discussions to bring the “iron horse” to the Ottawa valley began in 1848. In May of that year, The Packet, the precursor of The Ottawa Citizen, began to enthusiastically promote the building of a railway between Bytown, later to become Ottawa, and Prescott, a small community on the St Lawrence River. Prescott was immediately opposite Ogdensburg, New York which was to be the terminus of a railway linking the St Lawrence River to New York City and Boston. As the only way in or out of Bytown during winter was by sleigh, a rail link from Bytown to Prescott offered the tantalizing possibility of an all-season transportation route for exporting lumber cut from Ottawa valley forests to the important U.S. markets, one that was much speedier and less costly than using the Rideau Canal or the Ottawa River that were locked in ice for four months of the year.

Prescott’s leading citizens held an exploratory meeting with engineers and surveyors in June 1848. A similar meeting took place at the Court House in Bytown the following month. Receiving wide support from both communities, the Bytown and Prescott Railway was incorporated by an act of the Provincial government on 10 May 1850. A prospectus was issued describing the length of the line, its likely location, and its construction and outfitting costs, estimated at £150,000-200,000 (£1=C$4.87). To make it pay, annual revenues of £21,000-30,000 were needed. The possibility of extending the line eastward to link up with the Lachine to Montreal railway was also mooted. The line’s chairman was John McKinnon, the son-in-law of Thomas McKay, whose company helped to build the Rideau Canal, and who was a major lumber mill owner in New Edinburgh, a village he started.

Through the winter of 1850-51, the surveyor, Walter Shanly, with two assistants, mapped out four possible routes from Prescott to Bytown, covering more than 300 miles on snowshoe. On 7 April 1851, Shanly gave his report to the president and directors of the railway company. While stressing the preliminary nature of his survey, he favoured a route to the east of the Rideau River that took the tracks from Prescott through Spencerville, Oxford, Kemptville, Osgoode, Manotick, and Gloucester, before arriving in Bytown. While the terminus at Prescott on the St Lawrence was not controversial, the location of the Bytown terminus was. Some shareholders favoured a spot beside the Rideau Canal Basin (roughly where Confederation Park and the Shaw Centre is located today), while others wanted to build the station on land originally set aside for the military between Nepean Point and the Rideau Falls. The latter option was chosen. It was perhaps not entirely coincidental that the train would conveniently pass in front of Thomas MacKay’s lumber mills. With hindsight, Lebreton Flats, which later was to become the centre of Ottawa’s lumber industry, would have been a much better location, but at the time the area was largely undeveloped.

Funds to build the railway were raised partly by subscription from private shareholders, partly from municipalities, and partly through loans raised in England and Canada. Unfortunately for the railway’s backers, the line, only 52 miles long, was too short to qualify for the provincial subsidy. However, Bytown kicked in £15,000 in equity, and, after the 1852 Municipal Loan Act was passed, provided a massive loan guarantee of £50,000. Tiny Prescott, with a population of only 2,000, provided another £8,000 in capital and £25,000 in loan guarantees. The township of Gloucester chipped in a further £5,000 in equity financing. The links between the towns that provided support, the railway’s largest shareholders, and the railway’s most prominent advocate were unhealthily close, at least by today’s standards. Robert Bell, editor and later owner of the Ottawa Citizen, was the railway’s secretary, as well as a Bytown councilman. John McKinnon, the company’s president, was the reeve of Gloucester.

Workers started to clear land for the railway in early September 1851, with the official ground-breaking ceremony held on 9 October, 1851. A celebratory parade started in front of the railway office on Rideau Street and made its way down Sussex Street. On hand for the big event, were Bytown’s mayor, members of the Town Corporation, the directors and officers of the Bytown and Prescott Railway, a senior magistrate, the area’s member of parliament, the county sheriff, and the “Sons and Cadets of Temperance” in full regalia. That evening, McKinnon and the directors hosted a self-congratulatory dinner at “Doran’s,” a top Bytown hotel. Notwithstanding the presence of temperance followers in the afternoon parade, copious amounts of champagne and wine was consumed, leading to a “number of jovial songs…sung in the course of the evening.”

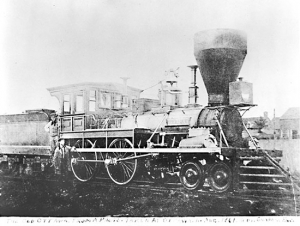

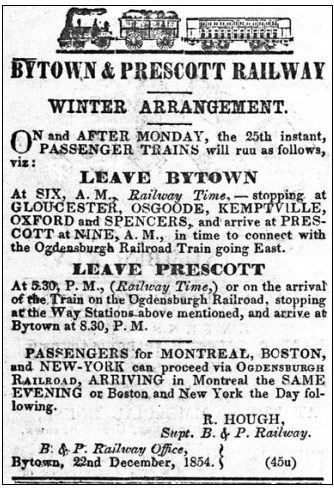

Advertisement that appeared in The Ottawa Citizen, 23 December 1854Construction was initially slow but for the most part straightforward; Shanly had done a good job siting the tracks. The most difficult part was crossing a swamp north of Prescott. Here, engineers laid down a wooden causeway as a bed for the train tracks. Once the rails arrived from England from the Ebbw Vale Iron Company in late 1853 and early 1854, the pace of construction picked up. The railway company laid down a narrow 4 ft 8 1/2 in. gauge track, commonly used in the United States and elsewhere, rather than the broad 5 ft 6 in. “provincial” gauge typically used in Canada at that time. The carriages and locomotives were sourced in the United States, with the first locomotive, the “Oxford” delivered by barge in May 1854. Two more, the “St Lawrence and the “Ottawa,” arrived in July. Immediately, the locomotives and carriages were put into service, servicing Kemptville by August, and Gloucester, just three and a half miles from Bytown, by 11 November.

Advertisement that appeared in The Ottawa Citizen, 23 December 1854Construction was initially slow but for the most part straightforward; Shanly had done a good job siting the tracks. The most difficult part was crossing a swamp north of Prescott. Here, engineers laid down a wooden causeway as a bed for the train tracks. Once the rails arrived from England from the Ebbw Vale Iron Company in late 1853 and early 1854, the pace of construction picked up. The railway company laid down a narrow 4 ft 8 1/2 in. gauge track, commonly used in the United States and elsewhere, rather than the broad 5 ft 6 in. “provincial” gauge typically used in Canada at that time. The carriages and locomotives were sourced in the United States, with the first locomotive, the “Oxford” delivered by barge in May 1854. Two more, the “St Lawrence and the “Ottawa,” arrived in July. Immediately, the locomotives and carriages were put into service, servicing Kemptville by August, and Gloucester, just three and a half miles from Bytown, by 11 November.

When the first train arrived in Bytown is a bit controversial. An advertisement placed by the railway in the Ottawa Citizen, dated 14 December 1854, informed its Bytown customers that “trains will start from the Montreal Road near the Rideau Bridge, at the East end of Bytown, at 7 o’clock, A.M. (Railway time).” Simultaneously, the railway discontinued its temporary stage coach service from Bytown to the Gloucester train station. The place of embarkation was just outside Bytown’s city limits. Most authorities place the date of the first train as Christmas Day, 1854, based in part on a later newspaper advertisement which said the train would leave Bytown at 6am, Railway time, staring on 25 December (see above). However, in a speech given eleven years after the event, President Bell of the Railway said the date of the first train was 29 December. Differences in timing may relate to when the Rideau Bridge was finally ready for rail traffic, whether the train carried freight or passengers, or the fog of memory. The official opening of the line occurred on 10 May 1855, exactly five years after the railway company was incorporated. Its name was also changed from the Bytown and Prescott Railway to the Ottawa and Prescott Railway to reflect the city’s new name.

Like many similar ventures of the period, the railway never lived up to the hopes of its shareholders and creditors, and was quickly in financial difficulty. An economic depression in the late 1850s cut into the revenues of the heavily-indebted line. The railway’s Ottawa station was also inconvenient for much of the city’s growing lumber industry located in Lebreton Flats. The building of other rail lines meant more competition and lower prices. At the Ottawa & Prescott’s annual general meeting in May 1863, a faction of shareholders tried to seize control of the failing company; an unseemly brawl ensued. Subsequently, with the railway bankrupt, the company’s senior creditors, most importantly, the Ebbw Vale Iron Company, assumed control. Shareholders and junior creditors, including the municipalities, got nothing. Following a corporate re-organization, the line re-emerged in 1867 as the St Lawrence and Ottawa Railway. In 1881, the Canadian Pacific Railway took over the line, and began using it as a feeder link to its main east-west route. Declining traffic during the 1950s led to the closure of the line, and its rails pulled up. Much of the route was converted into a recreational path. In downtown Ottawa, the Vanier Parkway was constructed where the old Bytown & Prescott Railway used to run. A portion of the old line’s route is still used today by Ottawa’s “O” train.

Sources:

Churcher, Colin, 2005. The First Railway in Ottawa, http://www.railways.incanada.net/Articles/Article2005_1.html.

——————, 2005. First Trips and Early Excursions in the Ottawa Area, http://www.railways.incanada.net/circle/excursions.htm#B&Psod.

Elliot. S. R., 1979. Bytown & Prescott Railway, Bytown Railway Society.

Pilon, Henri, 1972. “Robert Bell (1821-73),” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bell_robert_1821_73_10E.html.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1851. “Report, Bytown and Prescott Railway Office, Prescott,” 26 April.

———————-, 1851, “no title,” [official opening of the Bytown and Prescott Railroad], 11 October.

———————-, 1854, “Bytown & Prescott Railway,” 16 December.

———————-, 1854, “Bytown & Prescott Railway,” 23 December.

———————-, 1862. “Railway Celebration,” 23 August.

———————-, 1863, “The Railway Meeting, Disgraceful Scenes!” 22 May.

The Packet, 1848, “The Ogdensburg Railway,” Bytown, 13 May.

————-, 1848. “Proceeding of a Meeting of the Inhabitants of the town of Prescott,” 19 June.

————–, 1848. “Most Important Intelligence – Prescott & Bytown Railroad,” 24 June.

————–, 1848. “Prescott and Bytown Railroad from Prescott Telegraph,” 24 June.

————–, 1848, “Bytown & Prescott Railroad,” 7 July.

————–, 1850. “Prospectus of the Bytown & Prescott Railroad, 30 November.

————–, 1851. “Public Meeting in Gloucester.” 19 April.

————–, 1854, “Bytown & Prescott Railroad, 6 May.

Vanier Now, 2013. The History of the Vanier Parkway-Part One: Bytown and Prescott Railway Company, http://vaniernow.blogspot.ca/2013/02/the-history-of-vanier-parkway-part-one.html.

Images: Churcher, Colin, “All Change at Prescott,” picture of the Ottawa & Prescott Railway’s locomotive “Ottawa,” circa 1861, https://churcher.crcml.org/Articles/Article2008_01.html

Bytown & Prescott Railway Advertisement, The Ottawa Citizen, 23 December 1854.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.