James Powell

UFOs, a Cursed Box, and Science

You might be wondering what UFOs, a cursed box, and science have to do with each other. The answer: all can be found at the National Research Council of Canada on Sussex Drive. In mid-August, Steven Leclair, chief archivist at the NRC, kindly hosted a second group of HSO members on a tour of the NRC’s Sussex Drive facility. Leading us through this remarkable neoclassical structure built to the exacting specifications of Henry Marshall Tory in the 1930s, he pointed out its many architectural and design features. Most importantly, its offices can be easily converted into laboratories and back depending on need. They are also safely isolated from each other in case of an explosion! In fact, so well designed is the building that its laboratories continue to be used for scientific research today, more than 90 years after the building opened for business.

All was quiet in the building when we visited. Our footsteps provided the only sound as we passed down its yellow brick corridors. There was none of the usual hustle and bustle found in your typical office building. The only evidence of anybody working were white-coated scientists visible through glass-panelled doors. Signs posted beside each entrance provided scant clues to what was happening within. Truly this building is a “Temple of Science,” a moniker given to the NRC years ago by a visiting British dignitary.

In addition to the tour, Steve provided a wonderful lecture on the early years of the NRC. He talked about some of the inventions developed at the site, including an early voltage-controlled synthesizer called the Electronic Sackbut by Hugh Le Caine in the 1940s—the forerunner of the Moog synthesizer.

The last stop of the tour was Steve’s “holy of holies”—the archives. Up in his light-filled office on the top floor, Steve showed us treasures seldom seen by the public. This included a mysterious padlocked box. Recently rediscovered, the box had been hidden decades ago by an eccentric researcher who erroneously though he had made an important nuclear discovery. Fearful that his findings might fall into the wrong hands, he hid them in the box, saying that they could only be accessed by the NRC’s archivist when there was world peace. Any breach of these conditions would lead to a curse being placed on the opener. So far, Steve has withstood the temptation to peek inside.

Steve also told us that UFOs give him a lot of grief as the NRC is the repository of all Canadian reports of unidentified flying objects. So far, the NRC has been able to provide plausible explanations for the sightings. No sign of extraterrestrials has been found…yet.

Finally, Steve took the opportunity to tell us that the NRC’s archives are open to the public free of charge. All one need do is ask. Already, tens of thousands of documents and photographs have been digitized and are available on-line. Thanks to Steve’s efforts, these include documents and blueprints related to the fabled Avro Arrow aircraft, the acme of Canadian technical sophistication of the 1950s.

Thank you, Steve, for such an informative and engaging presentation and tour.

The Arrival of Traffic Lights

5 March 1928

It’s hard to imagine city driving without the ubiquitous traffic lights that govern the ebb and flow of cars, trucks, cyclists and pedestrians on our streets and avenues. For the most part, we take them for granted. But when a power failure temporarily puts out the lights, the resulting gridlock reminds us how much we rely on them to keep our roads safe and traffic flowing. In contrast, back in the days before the arrival of the automobile when life moved at a more leisurely pace, there was little in the way of traffic controls. Even whether one should keep to the left or to the right was uncertain. As well, everybody had the same right to use the streets and highways as long as one took care not to injure others. Intermingled among horse-drawn delivery wagons, hansom cabs and omnibuses were cyclists and pedestrians. Not only was jaywalking an unheard-of offence, people thought nothing of strolling down the centre of the street.

The pace of life began to quicken in the late nineteenth century with the introduction of electric streetcars. But the arrival of the automobile in large numbers early in the twentieth century was the real game changer. With the rules of the road ill-defined, city streets had become increasingly dangerous. Traffic control became a priority in all major cities. To gain an appreciation of the chaotic traffic conditions in a major North American city during the early 1900s, here is a link (San Francisco Street Scene) to a fascinating short film of a drive down Market Street in San Francisco just days before the famous earthquake devastated the city in 1906.

Traffic lights actually predate the automobile. In late 1868, gas-lit signals were installed at the intersection of Bridge, Great George and Parliament Streets close to the Houses of Parliament in London to help control heavy horse-drawn and pedestrian traffic. Adapted from railway signals by engineer John Peake Knight, the three semaphore signal arms stood on a pillar twenty-two feet high. The horizontal signal arms indicated “stop” and “proceed with caution.” At night, gas lights were used with coloured lenses. Similar to today, a red light indicated that traffic should stop and a green light “proceed with caution.” The lights and signals were manually controlled by a police constable who would also blow a whistle to indicate he was about to change them. Although the new invention was effective at controlling traffic, a month after its installation a gas leak led to an explosion that severely injured the attending constable. This effectively scuppered gas-powered traffic signals in London.

Fast forward to the early years of the twentieth century, manually-powered semaphore traffic signals were used in many American cities to help control traffic. Like their British counterpart, the arms indicated whether traffic should stop or go. Instead of gas, kerosene was sometimes used to light lamps at night, with the standard red or green lenses indicating “stop” and “go,” respectively. In 1923, the inventor Garrett Morgan of Cleveland successfully took out a U.S. patent (# 1,475,024) for a hand-cranked semaphore traffic signal that featured three positions: stop, go, and all stop so that traffic could give way to pedestrians. Morgan reportedly sold his invention for $40,000 to the General Electric Company, a considerable sum in those days.

Traffic lights as we know them date from 1912 when one Lester Wire of Salt Lake City, Utah, who was head of the city’s traffic squad, invented a two-colour, red-green system. Wire never patented his device though it was apparently employed in Salt Lake City. In 1913, James Hoge of Cleveland submitted a patent in the United States for an electric “Municipal Traffic Control System” that consisted of “traffic control boxes or signals at street intersections and other suitable points.” Hoge’s objective was to permit policemen to better control traffic in order to give priority to emergency vehicles. Lamps of different colours would be used with one colour (red) to indicate “stop” and another colour (white) to indicate “move.” He received his patent (# 1,251,666) on 1 January 1918.

The modern, three-colour (red, amber, and green), electric traffic light, first appeared on street corners in Detroit in 1920. Its inventor was William L. Potts, a police officer who, like others at that time, was concerned about worsening road safety owing to the increasing popularity of the automobile. Like Lester Wire before him, Potts did not patent his device, apparently because being a government employee he was not eligible to do so. Within a few years, Potts’s three-colour, electric traffic lights were being widely used in American cities.

Electric traffic lights came to Canadian streets in 1925, first in Hamilton, Ontario and shortly afterwards in Toronto as a means of reducing the number of police constables directing traffic at major intersections. Taking note of Toronto’s favourable experience with traffic lights, police magistrate Charles Hopewell wrote in late 1927 to Ottawa’s Mayor John Balharrie and City Council recommending traffic lights of the three-colour variety be installed as an experiment at three major intersections on Sparks Street—at Bank, Metcalfe, and O’Connor Streets. He recommended against installing lights at the intersection of Sparks and Elgin Streets owing to uncertainty over government plans for the area. The Dominion government had recently expropriated land in this area, including the site of the old Russell Hotel, with a view towards beautifying Ottawa, which included widening Sparks and Elgin Streets. At each of the three chosen intersections, four traffic lights would be installed on the existing “Whiteway” lamp poles. Hopewell recommended the “Co-ordinated Progressive System” of traffic lights made by the Canadian General Electric Company over equipment manufactured by the Northern Electric Company, a forerunner of Northern Telecom. He estimated the purchase and installation costs at approximately $2,600 (about $37,000 in today’s money). After consulting the Ottawa Hydro-Electric Commission, the annual electricity cost for running the twelve sets of traffic lights, each equipped with three 60 watt bulbs, was estimated at $640.

Although Council supported Hopewell recommendation to install traffic lights on Sparks Street, the Police Commission in December gave the contract to Northern Electric rather than Canadian General Electric. The cost of buying its automatic traffic control system with twelve sets of lights was under $1,800, much lower than Hopewell’s initial estimate. The funds to buy the equipment came out of unused resources in the police department’s 1927 budget. Of the twelve sets of traffic lights, eleven were mounted horizontally on existing light poles. The twelfth was mounted vertically to see which configuration of lights would be more visible.

Although newspapers optimistically reported that the traffic lights would be ready for Christmas, it took longer than expected for the hydro company to connect them. Finally, shortly before 8am on Monday, 5 March 1928, the new, automatic traffic lights on Sparks Street were switched on. The street lights were synchronized to facilitate travel down the street. They were on a 45-second cycle, with a twenty-second green light, followed by a five-second amber caution light, and a twenty-second red light. Twenty seconds were deemed sufficient time to allow streetcars to unload and load their passengers. Initially, the lights were in operation Monday through Saturday. Extra police were on hand that first day to assist the public in observing the rules. Magistrate Hopewell was also there to witness the lights in use for the first time. He returned at noon to check how things were running.

Overall, the introduction of traffic lights went smoothly, though the volume of traffic was unusually light that first day, possibly owing to cold weather. The street cars were running normally, however, allowing police officials to check the timing of the lights. Groups of people stood around the street corners to watch the lights change colour. A number of car drivers and streetcar operators drove through red lights, but police overlooked the infractions owing to people’s unfamiliarity with the new system. Police also stressed that pedestrians should obey the lights as well.

The pedestal street lights installed on Wellington Street in 1928, The Ottawa Evening Journal, 28 November 1928.Naturally, there were complaints. Some motorists didn’t like the location of the lights. Magistrate Hopewell said it would take at least a week for the traffic lights to prove their efficiency. In the meantime, the system would be studied and improved, if necessary.

The pedestal street lights installed on Wellington Street in 1928, The Ottawa Evening Journal, 28 November 1928.Naturally, there were complaints. Some motorists didn’t like the location of the lights. Magistrate Hopewell said it would take at least a week for the traffic lights to prove their efficiency. In the meantime, the system would be studied and improved, if necessary.

The new lights were judged to be a complete success, and were quickly rolled out to other important road junctures, including the Sparks and Kent and the Bank and Laurier intersections a few months later. The operation of the street lights was also extended to Sundays.

Wellington Street received its traffic lights in late 1928 at intersections with Elgin, Metcalfe, O’Connor, and Bank Streets. Instead of installing the lights on existing poles, new pedestal-type traffic lights were erected—a first in Canada. The lights, with top red, middle amber, and bottom light green, were mounted on pedestals with a two-foot base, standing over nine-feet high. The city had hoped to have the new traffic lights in operation earlier in the year, but delayed their installation pending approval from Prime Minister Mackenzie King who took a personal interest in plans to improve the Capital. The traffic lights were synchronized so that automobiles travelling at twenty miles per hour from the Château Laurier Hotel to Bank Street would not have to stop. The Ottawa Evening Journal proudly noted that Ottawa was the only city in North America, other than Buffalo, New York, to have an entire thoroughfare equipped with these new type of lights.

From then on, there was no looking back. Traffic lights, proven effective at controlling the flow of traffic and improving road safety, were here to stay.

Sources:

About Money, 2016. “Garrett Morgan 1877-1963,” http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2012/03/the-origin-of-the-green-yellow-and-red-color-scheme-for-traffic-lights/.

Bio, 2016. “Garrett Morgan Biography,” http://www.biography.com/people/garrett-morgan-9414691#cleveland-tunnel-explosion.

Brown, J. E., General Manager, Ottawa Hydro-Electric Commission to Mr. C.E. Pearce, Board of Control, 1927. “Letter,” 24 October.

City of Ottawa, 1927. “Minutes,” Traffic Control System, 6 December.

Globe and Mail, 2015. “First electric traffic signal installed 101 years ago,” 5 August.

History, 2016. “First electric traffic signal installed,” This Day in History, August 5. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-electric-traffic-signal-installed.

Hopewell, Charles, Police Magistrate, to Mayor and Board of Control, 1927. “Letter.” 3 October.

——————————————————-, 1927. “Letter.” 5 December.

Idea Finder, 2007, “Traffic Lights,” http://www.ideafinder.com/history/inventions/trafficlight.htm.

Mark Traffic, 2016. “Traffic Lights Invented by William L. Potts,” http://www.marktraffic.com/traffic-lights-invented-by-william-l-potts.php.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1927. “Traffic Lights Installed For Holiday Rush,” 12 December.

————————————, 1928. “New Automatic Signal System In Operation.” 5 March.

————————————, 1928. “Wellington St. Traffic Lights Now Are Likely,” 27 April.

————————————, 1928. “Traffic Lights To Operate Sundays,” 7 May.

————————————, 1928. “Ottawa To Get Latest Types Signal Lights,” 28 November.

Today I Found Out, 2016. “The Origin of the Green, Yellow and Red Color Scheme For Traffic Lights,” http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2012/03/the-origin-of-the-green-yellow-and-red-color-scheme-for-traffic-lights/.

U.S. Patent Office, 1918. “Municipal Traffic Control Signal of J. B. Hoge, Patent Number 1251666,” 1 January, https://www.google.com/patents/US1251666.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Tea with Adrienne Clarkson

In January 2024, Andrea Bissonnette, Ben Weiss and myself had an extraordinary experience—the opportunity to sit down with Madame Adrienne Clarkson at the Château Laurier Hotel to have tea and chat about her past and Ottawa history more generally. For those who might need a reminder, after a stellar career as a journalist, Madame Clarkson was Canada’s governor general from 1999 to 2005, and the Historical Society of Ottawa’s patron.

The story began in the spring of 2023 when Andrea contacted the Historical Society of Ottawa regarding an old family photograph album that had originally belonged to her grandmother, Marie Albina Guilbeault. Andrea had inherited it following the passing of her mother, and offered the photos to the Society.

Although the Society no longer maintains a photo archive, we agreed to go through the album, scan photographs of interest, and then send the collection to the City of Ottawa Archives. Among Andrea’s fascinating photos was a picture of her great-grandfather, Arthur Guilbeault, who was a mayor of Eastview (Vanier) in the 1920s, and another of Zoë Laurier, the wife of Sir Wilfrid Laurier.

It took us some months to go through the album in detail. In January, Ben Weiss read a number of newspaper clippings, snipped by Andrea’s grandmother, about her son, Andrew (André) Bissonnette, who was Andrea’s father. Representing the Ottawa Technical Institute, Andrew had won third prize in a Rotary Club public-speaking contest held on April 1, 1955 at the Château Laurier Hotel. Perusing the articles more closely, Ben recognized the name of the second-place winner—16-year-old Adrienne Poy, the young immigrant girl from Hong Kong who was to become Canada’s 26 th governor general.

Ben contacted Madame Clarkson’s office and offered to send the newspaper clippings to her as a gift. Instead, Madame Clarkson graciously volunteered to receive them in person as she was soon to be in Ottawa to give an address on leadership at Carleton University.

After meeting at the City of Ottawa Archives where Andrea officially donated her grandmother’s photographs, Andrea, Ben and I trooped down to the Château Laurier, expecting a brief meeting with Madame Clarkson. Instead, she spoke with us for more than an hour. It seemed like she would have happily chatted longer had it not been for another appointment (which turned out to be with none other than Randy Boswell, the well-known journalist, professor and Society member!).

Madame Clarkson was delighted to receive the clippings and recalled the Rotary contest in detail. In the lead-up to the event, she had practised under the direction of her English teacher, Mr. Mann. She entered the Rotary inter-school contest by winning a similar public-speaking event at her school, Lisgar Collegiate. Madame Clarkson said that Mr. Mann had had a profound influence on her, giving her skills that had served her well through her life.

The topic of her young Adrienne Poy’s twelve-minute presentation was “The Problem of China.” She also had to speak extemporaneously for two minutes on the postal system. She clearly impressed the judges and the reporters covering the event. Indeed, her speech garnered more press coverage that that of the first-place winner, Tony Reynolds from Glebe Collegiate, who spoke on “Moral Rearmament.” Madame Clarkson recalled that “moral rearmament” had been a popular, neo-fascist philosophy during the 1950s. (A 1967 article that appeared in The Harvard Crimson called the movement simplistic, anti-intellectual, emotional, and irrational.) Madame Clarkson said that her second-place finish had come as a disappointment; she had hoped to take first place. Indeed, there had been a general feeling that she had performed better than Reynolds but lost owing to her gender. In the 1950s, women did not come first.

Responding to a question from Andrea, Madame Clarkson admitted that while she knew Andrea’s father, Andrew Bissonnette, she did not know him well. She gave Andrea a hug when Andrea revealed that she had never met her father as he had tragically died while her mother had been three months pregnant with her. To talk to somebody who had known her father, even a little bit, was very special.

Madame Clarkson went on to speak about her early life in Ottawa after her family arrived as refugees from Hong Kong in 1942. Her first recollection was falling off the steps of a streetcar. Landing in a snowbank, three-year old Adrienne Poy was fortunately uninjured. She also recalled that her mother didn’t know how to cook when they first arrived in the city. Francophone neighbours taught her how to prepare Western food. Later, Mrs. Poy learnt how to cook Chinese cuisine at a Chinese restaurant. Subsequently, the Poy family ate Chinese food on weekdays and Western food on weekends.

She also described the social and religious divides in Ottawa at the time—English versus French, Irish versus Francophones in Lowertown, and Catholics versus Protestants. One thing she did not experience was anti-Chinese bias, possibly because there were so few Chinese in Ottawa owing to the 1923 exclusion law that barred most Chinese from emigrating to Canada until 1947. But, even within Ottawa’s small Chinese community—just two Chinese restaurants—there was a divide between those who had owned land back in China and those with a water, or fishing background. Her mother would not allow young Adrienne to bring home Chinese children with a fishing heritage.

One thing that was strong in the Poy household was their attachment to the Anglican Church. Madame Clarkson’s parents had been married in Hong Kong by Bishop Ronald Hall, who became famous for the ordination of Florence Li, the Anglican Church’s first woman priest, in 1944. After living in an apartment on Sussex Avenue, the Poy family later moved to Laurier Avenue west to be closer to Christ Church Cathedral where her parents were active members.

When asked about why her family remained in Canada after the war, Madame Clarkson said that her parents had considered going back to Hong Kong. Indeed, many Hong Kong friends were expecting and hoping that they would return. However, her father, William Poy, was concerned about the future of the British colony given the rise of Mao Zedong, fearing that Hong Kong could not last more than two years after Mao’s takeover of mainland China. While his fears later proved to be mistaken, the family stayed in Ottawa.

Noting that her upcoming birthday fell on the Chinese New Year, Ben asked Madame Clarkson if that had any significance for her. She laughed, saying that it did for her mother. Mrs. Poy spent the last three weeks of her pregnancy in bed in the hope that her child would be born a “rabbit” instead of a “tiger.” Failing in that endeavour, she despaired that young Adrienne’s character would be too forceful, making it difficult for her to find a husband.

Madame Clarkson also talked about senior government positions. She said she had turned down an offer to become a senator as she felt that she didn’t have the temperament for the job. While she could do committee work, it wasn’t her preferred type of activity. The role of governor general was more in keeping with her leadership skills. One position she has particularly enjoyed is being Colonel-in-Chief of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, a role she has had since 2007. Madame Clarkson noted that she was only the third Colonel-in-Chief since the formation of the regiment in 1914, and is proud to be the first Canadian.

With her assistant indicating that it was 3:30pm, and time for her next appointment, Andrea, Ben and I gave our thanks and said our goodbyes. Before going, Ben gave Madame Clarkson a copy of Dorothy Phillips’ book on the Duke and Dutchess of Devonshire, Victor and Evie, British Aristocrats in Wartime Rideau Hall as well as Bill Galbraith’s work on Lord Tweedsmuir titled John Buchan: Model Governor General. He also gave honorary membership certificates to both Madame Clarkson and Andrea. We hope that both are able to join us for future events.

Banish the Fly!

1 July 1912

The best way of getting rid of Mr. Fly is to get rid of his boarding house and his breeding house—the rubbish heaps, the old barrel, the exposed manure pile, or whatever is usually found in a neglected city back yard. Ottawa Journal, 1913.

Musca domestica, the pesky housefly. Easily identified by the four black stripes on its thorax, the housefly, which measures about 5 to 7 millimetres, in length, can be found throughout the world wherever humans live. Indeed, the housefly has made a “career” of feasting on the detritus of humans and their domesticated animals. After mating, the female of the species lays her eggs in batches of 100 or more on rotting vegetable or animal matter, including carrion or feces. After a day or so, the larvae hatch and begin feeding. They mature in as little as two weeks depending on temperature conditions. A female housefly can live for about a month and can produce as many as 500 eggs during her lifetime. In the absence of avian and insectile predators, as well as humans armed with rolled up newspapers, two amorous flies can produce a gazillion descendants during a summer. Thankfully, this is not the case.

While houseflies play an important ecological role in recycling organic wastes, their habit of feasting on the garbage in the bin at the side of the house, or the dog poop in the backyard, before skittering over granny’s lemon chiffon cake is not an endearing feature. Consequently, they have long been considered a vector for the spread of disease. Their persistence and apparent clairvoyance are other annoying behavioural features. Who hasn’t futilely tried to discourage a determined fly from walking all over one’s arms or legs?

Sustained efforts to rid cities of the much-hated housefly took place during the early years of the twentieth century in major Eastern US cities, such as Cleveland, as well as in major cities in Canada, including Toronto, Montreal, Hamilton, and Ottawa. The objective was to curb the spread of disease, particularly tuberculosis, typhoid, and infant diarrhea, believed to be spread by houseflies.

Such efforts had many elements. First, cities introduced bylaws requiring their citizens to take steps to minimize the breeding grounds of flies by collecting and covering manure piles. Recall the prevalence of horses during this period; cars had yet to replace them to any significant degree. As one horse can produce ten kilograms of manure daily, equine waste disposal was a major problem. Much was simply left on the streets, thereby attracting flies. Second, public health organizations distributed literature to households on the habits of houseflies, their impact on public health, and how to kill them or, barring that, keeping food uncontaminated and homes pest-free. Third, children, often the Boy Scouts, were mobilized to kill the bugs and to spread the word; the rationale being to harness youthful zeal, and to educate the next generation who might be more open that their parents to new health ideas. Recall that the germ theory of disease was still relatively new during the early twentieth century. Many people still thought bad smells, called miasmas, were the cause of disease. The idea that flies could transmit disease by just walking on food was a novel concept for many.

In July 1912, the Montreal Daily Star hosted a “Swat the Fly” contest in Montreal, offering prizes totally an amazing $350—a huge sum at that time, equivalent to close to $10,000 today—with first prize being $25. The contest was open to all children, both boys and girls. The contest was a huge success. Nearly one thousand Montreal children answered the call, swatting approximately 25 million flies, and, more importantly, spreading the word about household hygiene. Their tally, which far exceeded the paltry tally of 1.5 million flies caught by Toronto kids, as well as those of cities south of the border, earned Montreal the title of “world fly-swatting champion.”

Ottawa Evening Citizen, 15 June 1912Ottawa also took up the anti-fly challenge. In May 1911, city council passed a bylaw requiring downtown stables to contain manure in bins with tight covers or to be connected to the sewers. At the time, the Ottawa Citizen estimated that as many as three-quarters of downtown stables were not doing this. As well, the enforcement of existing hygiene laws appears to have been lax owing to the cost of regular inspections. The newspaper opined that “the greatest single step towards the elimination of the house fly in Ottawa will be when all stable within the city limits whether by careful inspection, or otherwise, are compelled to follow the simple and easily kept rules which other cities have imposed thereon.”

Ottawa Evening Citizen, 15 June 1912Ottawa also took up the anti-fly challenge. In May 1911, city council passed a bylaw requiring downtown stables to contain manure in bins with tight covers or to be connected to the sewers. At the time, the Ottawa Citizen estimated that as many as three-quarters of downtown stables were not doing this. As well, the enforcement of existing hygiene laws appears to have been lax owing to the cost of regular inspections. The newspaper opined that “the greatest single step towards the elimination of the house fly in Ottawa will be when all stable within the city limits whether by careful inspection, or otherwise, are compelled to follow the simple and easily kept rules which other cities have imposed thereon.”

In June 1912, it was announced in the Ottawa Citizen that there would be an anti-fly contest in the nation’s capital running for two weeks beginning Dominion Day. Ottawa’s new slogan for the period was “Banish the Fly!” The contest was organized by the Public Health Committee of Ottawa’s local Council of Women in co-operation with the city’s department of health. The Council provided nine prizes with a total value of $25, with the event open to both boys and girls under fifteen years of age. The boy or girl killing the most houseflies would win $10, with second place earning $5. There were also three third-place prizes of $2 each and four fourth-place prizes of $1. Captured flies were to be turned over to the office of Dr. Shirreff, the city’s chief medical officer, at City Hall, for inspection and counting. Children could use any sort of container in which to bring their “catch.” Any method of fly-catching was acceptable except apparently for the use of “tanglefoot paper.” The newspaper said that the competition was “a new and vital form of educating people to a danger long overlooked or neglected,” and hoped that the campaign would get a good response so that “Ottawa will this summer be a most unpopular resort for the fly.” A similar “Swat the Fly” contest was also launched in Hull.

Consistent with doctors’ recommendations, the newspaper advised kids to catch flies outside before they had a chance to come inside and spread disease. Homeowners were told to equip all windows and doors with screens to keep out the pest, and to move rubbish and refuse away from back doors. The Citizen also recommended poison as the most efficacious means of killing flies. Helpfully, the newspaper provided recipes. The first was an innocuous mixture of the yolk of one egg, 1/3 cup of sweet milk, one level tablespoon of sugar, and one level tablespoon of pepper. Alternatively, it recommended a mixture of two tablespoons of formalin and 16 ounces of equal parts of water and milk. Regardless of the mixture used, the Citizen said that it should be placed in shallow plates, with a piece of bread floating in the middle to allow more room for the flies to land on. As a testimonial to the effectiveness of the formalin trap, it cited a Professor R. J. Smith of North Carolina who apparently caught 40,000 flies in a calf barn during a 16-hour period using the recipe.

One thing the newspaper neglected to mention, however, was the dangers of formalin. A lethal dose for an adult human is about 30 millilitres, the amount recommended by the newspaper in its fly poison recipe. Used for embalming purposes and in dilute amounts as an anti-bactericide, formalin, a colourless liquid, releases formaldehyde gas which is both flammable and poisonous. Dangerous to have around the house, and not something one would want children to handle, woe betide any thirsty household pet that might be attracted to the milk and bread mixture.

Despite the exhortations of the Citizen, the “Banish the Fly” contest got off to a slow start. More than a week into the campaign, only nine boys and one girl had entered. The city kept a running tally of each participant’s “kill” and issued receipts. Half way in, John Cooney of 138 Besserer Street was in the lead with a total of 20,000 flies out of a total of 46,500 turned into City Hall.

In case you were wondering, health department clerks didn’t laboriously count each fly. Instead, the flies, which were brought into city hall in bottles, envelopes, matchboxes, and even a talcum power can, were weighed. Their weight in grammes was then multiplied by 200 to get an approximate number of houseflies.

Public announcement, Public Health Committee of Ottawa’s Local Council of Women, Ottawa Citizen, 28 April 1915.Additional participants trickled in. By the close of the competition, twenty-two children—seventeen boys and five girls—brought a total of 458,300 flies to the Department of Health. In first place was eleven-year-old Roy Judd of 136 Besserer Street who had killed 61,700 flies. His preferred method was poison. In second place was Mortimer Thompson of 164 Hopewell Avenue. Ethel Moffat (age 12 years), of 143 Kent Street took the third position, and was the highest-scoring girl. John Cooney (age 10 years), who had been initially leading the competition came in fourth with 40,700 flies. John Cooney and Roy Judd, the ultimate winner, were next door neighbours. The youngest competitor was Clyde Swan of 201 Division Street (Bronson Avenue). The five-year old collected an impressive 7,600 flies.

Public announcement, Public Health Committee of Ottawa’s Local Council of Women, Ottawa Citizen, 28 April 1915.Additional participants trickled in. By the close of the competition, twenty-two children—seventeen boys and five girls—brought a total of 458,300 flies to the Department of Health. In first place was eleven-year-old Roy Judd of 136 Besserer Street who had killed 61,700 flies. His preferred method was poison. In second place was Mortimer Thompson of 164 Hopewell Avenue. Ethel Moffat (age 12 years), of 143 Kent Street took the third position, and was the highest-scoring girl. John Cooney (age 10 years), who had been initially leading the competition came in fourth with 40,700 flies. John Cooney and Roy Judd, the ultimate winner, were next door neighbours. The youngest competitor was Clyde Swan of 201 Division Street (Bronson Avenue). The five-year old collected an impressive 7,600 flies.

While anti-fly campaigns were launched in the years that followed, this was the only Banish the Fly contest held in Ottawa. Although the housefly population was barely dented, reviews were positive in that it helped to educate people about the relationship between public cleanliness and public health.

Whether the humble housefly deserved the opprobrium heaped upon it during the early twentieth century is less clear. According to Valarie Minell et al, the authors of Swatting Flies for Health: Children and Tuberculosis in Early Twentieth-Century Montreal, the housefly had been “vilified.” Indeed, today the house fly is generally viewed a nuisance rather than a major transmitter of disease. This probably reflects the fact that in urban areas there are now few horses and other forms of livestock, outhouses are a thing of the past, and kitchen waste is picked up weekly for composting. With fewer feeding grounds and hatcheries, housefly numbers are likely much smaller today than a hundred years ago. Nonetheless, Musca domestica is reportedly a carrier of hundreds of different forms of bacteria. Many of these bacteria are pathogenic to humans and can cause many diseases, including dysentery, tuberculosis, typhoid, and polio. To this long list, recent research has shown that the house fly can be a carrier of the bacteria H. pylori that can cause stomach ulcers.

So, the next time you spot a housefly, swat it.

Sources:

Khamesipour, F., Lankarani, K. B., Honarvar, B. & Kwenti, T. E., 2018. “A systemic review of human pathogens carried by the housefly (Musca domestica L.), BMC Public Health, Article No. 1049.

Minnell, Valerie. & Poutanen, Mary-Anne, “Swatting Flies for Health: Children and Tuberculosis in Early Twentieth-Century Montreal,” Urban History Review, Vol. 36, No.1 Fall 2007.

Ottawa Journal, 1911. “No Title,” 22 March.

——————-, 1911. “The Sanitary Inspection,” 12 June.

——————-, 1913. “One City Conquers Mr. Fly.

Ottawa Citizen, 1911. “Anti-Fly Bylaw,” 29 October.

——————, 1912. “Premium On Flies,” 7 June.

——————, 1912. “The Anti-Fly Campaign Gives Boys And Girls Chance To Earn Money,” 15 June.

——————, 1912. “Here He Is! Swat Him!” 1 July.

——————, 1912. “After Hull Flies,” 4 July.

——————, 1912. “Early Swatting,” 10 July.

——————, 1912. “An Educative Campaign,” 10 July.

——————, 1912. “Fly Campaign,” 11 July.

——————, 1912. “Fly Swatters Who Win Prizes,” 16 July.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Victorian Order of Home Helpers, a.k.a. The VON

10 February 1897

By early 1897 Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee was fast approaching. Across Canada, communities and governments were trying to decide on how best to mark this historic event. On 10 February 1897, a public meeting was held under the auspices of the National Council of Women of Canada in the assembly hall of the Normal School on Elgin Street to discuss a proposal to establish the Victorian Order of Home Helpers as a means of honouring the Queen’s long reign. This idea was consistent with the Queen’s wish that celebrations be connected with efforts to alleviate the suffering of the sick and poor. The Council’s president was the Countess of Aberdeen, the wife of the Governor General. Lady Aberdeen, born Ishbel Marie Marjoribanks, was a woman of extraordinary energy and ability. An early feminist, she had founded a number of charitable organizations in her native Scotland that focused on poor women. Following her husband’s appointment as Canada’s Governor General, she founded in 1894 the National Council of Women of Canada, and was the Council’s first president.

Lady Aberdeen, 1898, Library and Archives CanadaThe idea of a national organization of “Home Helpers” originated in western Canada, possibly at a meeting of the Vancouver local council of women and Lady Aberdeen. Another report suggested that the idea came from the local council of Victoria, and was later forwarded to the National Council of Women. Regardless, Lady Aberdeen was an early supporter and quickly became identified with the proposal.

Lady Aberdeen, 1898, Library and Archives CanadaThe idea of a national organization of “Home Helpers” originated in western Canada, possibly at a meeting of the Vancouver local council of women and Lady Aberdeen. Another report suggested that the idea came from the local council of Victoria, and was later forwarded to the National Council of Women. Regardless, Lady Aberdeen was an early supporter and quickly became identified with the proposal.

The public meeting at the Normal School was well attended. With the Governor General and senior government officials present, including the Premier, Wilfrid Laurier, Lady Aberdeen addressed the assembly. She stressed the debt owed by women to Queen Victoria—“no section of Her Majesty’s subjects have more cause to sing the praises of this glorious epoch than the members of Her Majesty’s own sex.” She noted that new possibilities had opened up for women during the Queen’s reign. The Queen has demonstrated that a woman can “have an intimate knowledge and grasp of the affairs of state whilst at the same time being a model of all womanly, wifely, and motherly virtues and charms.”

Speaking about the proposed scheme, Lady Aberdeen said Home Helpers would need to have a practical knowledge of midwifery, first aid, home-keeping, simple home sanitation, and the preparation of food for invalids. She thought that a “Home Helper” would be “constantly visiting homes in need—would be giving advice, cheering the home and doing various acts of mercy and kindness.” Successful applicants, who would have to pass an examination set by the medical profession, would be supplied with a uniform and the badge of the Order.

She estimated that $1 million was needed to ensure that funds would be available in perpetuity. Local women’s councils would undertake collections in co-operation with others. The Bank of Montreal agreed to receive subscriptions.

At the public meeting, Wilfrid Laurier, moved the following resolution, seconded by Clifford Sifton, the Minister of the Interior:

That this meeting heartily approves of the general character of the scheme described as the Victorian Order of Home Helpers as a mode of commemoration by the Dominion of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, and that a fund be opened for the carrying out thereof.

Despite governmental support, Lady’s Aberdeen’s Order of Home Helpers met mixed reviews, especially from members of the medical profession. Although doctors in Montreal, including Professor Craik, the dean of McGill’s medical school, supported the plan, it was rejected by others, including the Ontario Medical Association, as being impractical and even dangerous. Many feared that well-meaning but otherwise under-qualified women would be sent out to administer to the sick.

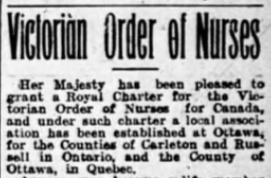

In part as a way to alleviate these concerns, the name of the scheme was quickly changed to the Victorian Order of Nurses (VON). The plan was also tweaked to make it clear that only highly-qualified nurses would qualify for the Order. The VON’s objectives were also clarified. They were: i) to provide skilled nurses in sparsely settled regions of the country; ii) to provide skilled nurses to attend sick poor people in their own homes; iii) to provide skilled nurses to attend cases in cities at fixed charges for persons of small incomes; iv) to provide cottage hospitals or small lying-in rooms in homes; and v) to train nurses to carry out these objectives. Nurse salaries, estimated at $400-500 per year, would be paid by the Order, with any fees collected by nurses from those who could afford them to be sent to the Order.

Despite these changes, opposition continued. Many doctors believed that it would be better if physicians and surgeons were paid bonuses to go out to frontier districts, or if funds were used to expand existing hospitals. Others doubted whether “even a very strong-minded female,” would be physically up to the rigours of a north-western winter if called out in the middle of the night.

Lady Aberdeen and other officials worked hard speaking to groups across the country to drum up support for the Victorian Order of Nurses and to dispel rumours that only minimally trained nurses would be hired. They also stressed that instead of replacing doctors, the nurses would, to the extent possible, be working under their direct supervision. This helped. In Winnipeg, the Manitoba Morning Free Press, which had been a fervent opponent to the scheme, was converted. Instead of believing that the Victorian Order of Nurses was “a well-meaning fad” that was “ill-digested, unwise and impractical,” as it had earlier opined, it concluded that “as the scheme becomes better known and its aim better understood, opposition and indifference will disappear.” The paper chided Winnipeg doctors for not attending a public meeting where details of the scheme were presented.

Some criticisms became very personal. The Halifax Herald attacked Lady Aberdeen. It wrote that the proper commemoration of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee was being “frustrated through Lady Aberdeen’s inability to mind her own business.” It was a “thoroughly quixotic scheme” and that “we expect our Governors-General to so govern their own families as to keep them out of mischief.” The New York Evening Post said that Lady Aberdeen was not popular in Canada, being “too clever and too advanced for Canadians.” Instead of paying attention to “etiquette and raiment,” she was “too much interested in ‘movements.’” Clearly the sight of an independent woman striving to make a difference in a male-dominated world was too much to stomach for some members of the public.

Given such criticisms, Lady Aberdeen must have received a much welcomed confidence boost when the British Medical Association and Lord Lister, the father of antisepsis, endorsed the Victorian Order of Nurses. She must have been similarly gratified when Florence Nightingale, the most famous nurse of all time, also came out in favour of her scheme.

Newspaper clipping announcing the granting of a Royal Charter to the Victorian Order of Nurses, The Ottawa Evening Journal, 3 June 1898.Here in Ottawa, weekly meetings were held through the spring of 1897 in the Governor General’s office in the Departmental building on Parliament Hill to get the VON up and running. A provisional management committee was established, comprised of some high-powered people, including Lady Ritchie, the wife of Canada’s Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Bishop of Ottawa, and Sir Henri Joly de Lotbinière, a former premier of Quebec, later to become the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. Four trustees were also appointed to manage the money that began to flow to the Order. Sandford Fleming, a resident of Ottawa and the father of world-wide standard time, was one of the trustees. In late April 1897, the VON was officially endorsed by Ottawa citizens at another public meeting at the Normal School. The indefatigable Lady Aberdeen presided.

Newspaper clipping announcing the granting of a Royal Charter to the Victorian Order of Nurses, The Ottawa Evening Journal, 3 June 1898.Here in Ottawa, weekly meetings were held through the spring of 1897 in the Governor General’s office in the Departmental building on Parliament Hill to get the VON up and running. A provisional management committee was established, comprised of some high-powered people, including Lady Ritchie, the wife of Canada’s Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Bishop of Ottawa, and Sir Henri Joly de Lotbinière, a former premier of Quebec, later to become the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia. Four trustees were also appointed to manage the money that began to flow to the Order. Sandford Fleming, a resident of Ottawa and the father of world-wide standard time, was one of the trustees. In late April 1897, the VON was officially endorsed by Ottawa citizens at another public meeting at the Normal School. The indefatigable Lady Aberdeen presided.

Slowly the money began to roll in. Subscriptions began at 5 cents. Both the great and small contributed. Sir Donald Smith (later Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal), the president of the Bank of Montreal and the man who hammered in the last spike on the Canadian Pacific Railway, donated $5,000, and pledged another $5,000 as soon as donations of $100,000 had been made by others contributing $1,000 or more. Meanwhile, fourteen children, the oldest aged 12, at a francophone school near Ottawa sent in their allowances. Their teacher attached a letter to Lady Aberdeen saying “The children of my school cannot pass this occasion to do something for Queen Victoria. Not being rich but having the will to aid the poor, they send you the amount enclosed.” The letter listed the names and ages of the children.

Although the scheme came nowhere near reaching the goal of $1 million, a huge sum back in those days, it received enough in donations and pledges, about $250,000, for it to proceed. On Jubilee Day, 22 June 1897, Lord Aberdeen, the Governor General officially announced the formation of the Victorian Order of Nurses as a lasting tribute to Queen Victoria.

Miss Charlotte MacLeod, First Chief Superintendent of the Victorian Order of Nurses, 1898, Library and Archives Canada.

Miss Charlotte MacLeod, First Chief Superintendent of the Victorian Order of Nurses, 1898, Library and Archives Canada.

The VON hit the ground running. Within its first year, Lady Aberdeen had acquired the home of Alderman Davis of Ottawa at 578 Somerset Street for the Order’s headquarters. VON training homes were also established in Ottawa, Toronto, Montreal and Halifax. Miss Charlotte MacLeod, who had worked with Florence Nightingale, was named as the VON’s Chief Superintendent. In the spring of 1898, four nurses were sent to help administer to the sick in the Yukon. At this time, tens of thousands of people were travelling to the Klondike in the great gold rush. Disease, owing to poor sanitation, was rampant. Lady and Lord Aberdeen bid the nurses au revoir with a dinner at Rideau Hall on the eve of their departure on their month-long journey to Dawson City.

In early June 1898, it was announced that the Victorian Order of Nurses had received a Royal Charter for Canada as well as a local charter for an Ottawa chapter for the counties of Carleton and Russell in Ontario, and the country of Ottawa in Quebec. Life membership in the Ottawa chapter was set at $100, with an annual membership costing $5. Quickly, Ottawa had 18 life members and 40 annual members. A meeting was also held in the committee room of the Ottawa City Hall to elect a board of management. With the now Sir Sanford Fleming in the chair, an all-woman, twelve-person board was elected. Prominent among them were Lady Laurier and Lady Ritchie.

In late 1898, Lord Aberdeen’s tour of duty as Governor General came to an end. But before the vice-regal couple left Ottawa, Lady Aberdeen received a letter from Colonel Evens, the commandant of the Yukon military contingent expressing his and his soldiers’ “sincere appreciation” for the services of the Victorian Order nurses. “The work of the Victorian Order in Dawson is a great one, and the opening of the new hospital was providential. Their presence with the force has been invaluable…I don’t know how we should have fared without them.”

In 2017, one hundred years after its founding, the Victorian Order of Nurses had 5,000 employees and 9,000 volunteers, and provided 75 home care, support and community services in more than 1,200 Canadian communities.

Sources:

Halifax Herald (The), 1897. “A Halifax Opinion,” in The Ottawa Evening Journal, 25 May.

Manitoba Morning Free Press, 1897. “Victorian Nurses,” 23 April.

————————————-. 1897. “The Victorian Fund,” 28 May.

————————————-, 1897. “Victoria Order,” 28 May.

————————————-, 1897. “Order of Nurses,” 28 May.

————————————-, 1897. “Victorian Order Of Nurses,” 31 May.

————————————-, 1897. “The Victorian Order,” 2 June.

————————————, 1897. “The Victorian Order,” 7 June.

————————————, 1897. “The Doctors And The Victorian Order,” 8 June.

The New York Evening Post, 1897. “Victorian Order of Nurses,” in the Vancouver Daily World, 12 August.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1897. “Victorian Home Helpers,” 11 February.

————————————-, 1897. “Some Explanations,” 3 March.

————————————-, 1897. “Getting Organized,” 19 March.

————————————-, 1897. “Citizens Will Meet,” 21 April.

————————————-, 1897. “Victorian Nurses,” 24 April.

————————————-, 1897. “Ottawa Is In Line,” 26 April.

————————————-, 1897. “Victorian Order of Nurses,” 14 June.

————————————-, 1897. “The Scheme Unpopular,” 13 July

————————————-, 1897. “Eager To Help, 20 July.

————————————-, 1898. “Klondike Nurses,” 28 March.

————————————-, 1898. “Music For Rideau Hall,” 31 May.

————————————-, 1898. “Victorian Order of Nurses,” 3 June.

————————————-, 1898. “Home For V.O.N.” 7 June.

————————————-, 1898. “Women’s Council,” 12 July.

————————————. 1898. “Victorian Nurses In The Klondike,” 1 October.

Vancouver Daily World, 1897. “Women Helpers,” 22 February.

—————————–, 1897. “Taking Practical Form,” 26 March.

—————————–, 1897. “Cablegram from Sir Donald Smith” 28 June 1897.

—————————–, 1897. “Victorian Order Of Nurses,” 1 October.

—————————–, 1898. “Training Home For Nurses,” 27 July.

VON Canada, 2017. http://www.von.ca/.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Fisher's 'Folly'

27 November 1924

By 1918, it had become apparent that the three principal hospitals serving Ottawa—the Water Street Hospital, established by Élisabeth Bruyère in 1845 as the Hotel-Dieu Hospital, the Carleton County Protestant General Hospital located on Rideau Street that opened in 1851, and St. Luke’s Hospital on Frank Street established in 1890—had become overstretched. The city’s population had grown considerably and continued rapid growth was expected. As well, its health facilities were increasingly being used by suburban communities. In May 1918, the Boards of the Protestant and St. Luke’s hospitals agreed at a joint meeting that they should send a “memorial” to Ottawa City Council noting the inadequacy of the city’ current hospital facilities and recommending the construction a new, large and modern 500-bed hospital.

The inadequacy of Ottawa’s health care system was dramatically revealed just a few months later with the arrival of the Spanish influenza epidemic in September 1918. Area hospitals were overwhelmed. Health officials were forced to open emergency hospitals, often in schools, in an attempt to deal with the overflow of cases. Before the epidemic petered out, there were roughly 10,000 flu cases and close to 600 deaths in Ottawa out of a population of less than 110,000.

The influenza pandemic had hardly ebbed when on 13 February 1919 more than 100 leading Ottawa citizens, supported by prominent community organizations, presented the two hospitals’ petition. Among a new hospital’s advocates were Mr. J.R. Booth, the lumberman, Sir George Burn, the head of the Bank of Ottawa, Mr. A.J. Freiman, the owner of Freiman’s department store on Rideau St, Warren Soper, one of Ottawa’s electrical barons, and Senator Belcourt, a noted francophone Liberal senator. Organizational support came from the Ottawa Board of Trade, the Rotary Club, the Retail Merchants’ Association, the Trade and Labour Council, the Ottawa Chapter of the Council of Women, the May Court Club, and the Women’s Canadian Club. The proposal called for the construction of a new 500-bed hospital at a cost of $1.5 million. The directors of the Protestant General and St. Luke’s indicated their willingness to merge and turn over all of their assets and properties to the city if the new municipal hospital was built.

Given such high-powered supporters, City Council, led by Mayor Harold Fisher who was a strong advocate for a new hospital, moved swiftly. Less than two weeks later, Council asked the province for authority to raise $1.5 million in debentures to pay for the new hospital. Over time, the authorized amount increased to $2.75 million as the initial estimates proved to be too low. Another $750,000 was needed for equipment. Prominent residents also provided additional funding. R.M. Cox, a lumberman, left almost $500,000 in his will to the new hospital. Hiram Robinson bequested $100,000 to fund a 70-bed children’s wing, while ex-alderman W.G. Black left $100,000 for the maintenance of the hospital grounds.

As one would expect, the site for the new hospital was contentious. Three successive reports through 1919 looked at potential locations which included Regan’s Hill in Sandy Hill, the Slattery-Bower property in Ottawa East, and Dow’s Lake at the corner of Bronson Street and Carling Avenue. In the end, the final report narrowed the choices down to two—the Protestant Hospital site on Rideau Street and Reid Farm out on the fringes of the city across from the Experimental Farm. The Boards of both the Protestant General and St. Luke’s Hospital unanimously supported the Reid Farm location. While somewhat distant from downtown, though only twelve minutes by car from the Post Office on Sparks Street (now the site of the War Memorial), it offered fresh, country air—a major consideration in these years before air conditioning. As well, the population of the western part of the city was growing rapidly, something that was expected to continue over the coming decades.

After considerable debate, City Council voted 16-4 in early November 1919 to purchase a 23.5-acre portion of Reid Farm for the new Civic Hospital. The price tag was $77,850. The minority on Council who voted against the site were primarily concerned about the distance of the hospital from the bulk of the city’s population, as both the Protestant General and St. Luke’s would close when the new Civic Hospital opened its doors. Alderman Pinard, the leader of the minority, said that while he accepted the point that Reid Farm might be the right site in fifty to one hundred years, one had to also consider the present.

Interestingly, there is no contemporaneous reference in either the Ottawa Citizen or the Ottawa Journal newspaper to “Fisher’s Folly,” the moniker later widely given to the Civic Hospital. While Mayor Fisher was indeed in favour of locating the hospital in Reid Farm, so was most of City Council as well as the hospitals. While there was some community opposition, there was no widespread skepticism as the name suggests. The first reference in the press to “Fisher’s Folly” didn’t seemingly occur until 1959. Subsequent retellings of the Civic Hospital story picked up on this catchy though likely misleading name.

Reid Farm, located in Hintonburg, was bounded by the train tracks to the north (now the Queensway), Fairmont Avenue in the east, Parkdale Avenue in the west and Carling in the south. Reportedly some 200 acres of land was purchased from the Crown in 1829 by one John Anderson who offered to sell 100 acres to John Reid. They tossed a coin to decide who would take the southern or the northern portion. Anderson won the toss and opted for the northern half leaving Reid with the southern portion. Reid and his wife came to settle on the land in 1832, having bought farm implements and oxen. The couple initially lived in a log house before constructing a stone building. At that time, the farm was located in a virtual wilderness, with only a rough trail leading through the woods to Richmond Road. Robert Reid lived on the farm until his death in 1889 when it passed to his son, Robert Jr. and his daughter Agnes, who in turn sold the land to the city and developers. Robert Junior died in 1923 and his sister Agnes, the last of the Reid family, in 1925.

Excavation work on the new Civic Hospital began in July 1920. The architects for the project were Stevens & Lee of Toronto, a firm that had built a number of hospitals across Canada, including Halifax’s Children’s Hospital, the General Hospital in Kingston, and the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. General contractors were Ross-Meagher Co. and Alex I. Garvock.

While the hospital was initially expected to open its doors by the end of 1921, there were a number of delays, caused in part by labour issues and supply problems, which pushed the deadline out until the end of 1924. The enterprise was also massive, employing more than 300 workers. Two million bricks were used along with 250,000 terra cotta blocks. It was calculated that there were seven miles of walls.

The new Civic Hospital opened on 27 November 1924 with the Hon. Lincoln Goldie, the Provincial Secretary and Registrar of Ontario, officiating. Also present for the big day was Ottawa Mayor Champagne and former mayor Harold Fisher who was now the Liberal MLA for Ottawa West. He was also a member of the Board of Trustees for the new hospital. Fisher said that it was the greatest day of his life. More than 1,000 guests attended the opening ceremonies. Over the following three days, the general public came to view the new, state-of-the-art hospital facilities.

The Civic Hospital campus comprised of five buildings. The main building was designed in the shape of an “H” with open courts facing both north and south. On the ground floor was the admitting department, the entrance for ambulances, the X-ray department, the isolation unit, as well as the psychiatric and hydro-therapy departments. There was a special admitting department for maternity cases as well as a dedicated elevator to take expectant mothers to the 80-bed maternity ward. There was also a children’s department with playrooms.

The 550-bed hospital had public, semi-private and private wards, with the largest ward having 16 beds. Each bed was equipped with a washstand with hot and cold running water and a mirror. Screens provided privacy. Private patients had private lavatories, with a bath shared between every two rooms. Private patients could also have a telephone for an additional fee. There were two sunshine rooms and three large airing balconies for patients. The top (sixth) floor was the location of the operating and surgical departments with four major operating rooms, an eye-operating room, a plaster room and rooms for other ancillary activities, including sterilization, workrooms and service. Natural lighting was provided for the operating rooms by means of high, vertical, sash windows. The floors in the building were covered in jasmine-coloured “Battleship” linoleum. Western and southern facing walls were painted in tints of French grey while northern and eastern walls were painted a buff colour.

Four other buildings were linked by underground tunnels to the main building. To the north was a service building which housed the principal kitchen, hospital stores, and staff dining rooms. Its upper floors were used as accommodation for resident staff. North of the service building was the power house that provided electricity and refrigeration. There were also boilers for central heating and laundries. A nurses’ home faced Parkdale Avenue, providing single rooms for all nurses along with parlours, entertainment and living rooms. Finally, there were a building for servants, quarters for carpenters and painters, as well as an incinerator.

Shortly after the Civic Hospital opened for business, the old Protestant General and St. Luke’s hospitals were closed as was the old Ottawa Maternity Hospital located at the end of Rideau St. near the Cummings Bridge and the adjacent Lady Stanley Institute nursing school. Beginning at 9:30am on 17 December 1924, forty-four patients from the Protestant General were ferried over to the Civic. Those bedridden arrived by ambulance, while ambulatory public ward patients were transported by bus. Private and semi-private patients came by taxi. The first patient to be admitted to the Civic was Donald MacIvor from Niagara Falls, a veteran patient of the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment. Patients from St. Luke’s were transferred several days later.

Fast forward a hundred years, work is underway to replace the now aging Civic campus of The Ottawa Hospital with a new hospital that will meet the needs of Ottawa residents into the 22nd century. As was the case in 1919, there has been considerable controversy about the location of the new hospital. A proposal to site it on the other side of Carling Avenue across from the existing hospital met with widespread opposition since it meant carving out land from the Central Experimental Farm—a National Historic Site and a treasured part of the greenbelt. A new site close to Dow’s Lake, which had been the previous location of Agriculture Canada’s Sir John Carling building imploded in 2014, was subsequently chosen with The Ottawa Hospital signing a 99-year lease with the federal government. The principal access to the new hospital complex will be via Carling Avenue.

Fittingly, construction of the $2.8 billion dollar, 641-bed hospital is expected to begin in 2024, one hundred years after the first Civic Hospital opened its doors. The new hospital is expected to be operational in 2028.

Sources:

New Civic Development for the Ottawa Hospital, 2021, https://newcivicdevelopment.ca/.

Ottawa Citizen, 1919. “Three Reports Made. Final Choice Narrowed Down To Farm And Protestant Hospital.

——————, 1919. “Hospital Board Favor Reid Farm,” 3 November.

——————, 1919. “Council Decides On Reid Farm As Site Of Hospital,” 4 November.

——————, 1923. “Death Of Robt. Reid, An Ottawa Pioneer,” 9 October.

——————, 1924, “Gives An Idea Of Its Immense Size,” 28 November.

——————, 1924. “Group Of Five Buildings Is Comprised In Civic Hospital,” 28 November.

——————, 1924. “Capital City’s Facilities For Care Of The Sick Unsurpassed As Result Of Its Construction,” 28 November.

——————, 1924. “Patients In Comfort To Civic Hospital,” 17 December.

——————, 1925. “Was Last Survivor Of Pioneer Family,” 11 March.

——————, 1985. “Ottawa Civic Hospital,” 25 April.

——————, 1989. “Civic turns 65 today,” 17 December.

Ottawa Journal, 1919. “Leading Citizens Ask For Modern Municipal Hospital,” 14 February.

—————–, 1924. “Civic Hospital Movement Initiated Six Years Ago Has Interesting History,” 28 November.

—————–, 1924. “Easy To Operate Civic Hospital Up To Capacity,” 28 November.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Hatpins & Defiance: The Battle in Ottawa against Regulation 17

Members and guests who attended the October 2022, in-person, HSO presentation at the Auditorium of the Main Branch of the Ottawa Public Library were treated to a tour de force by Jean-François Lozier, Curator at the Canadian Museum of History. Jean-François told a story that, while familiar to Ottawa’s Francophone community, is mostly unknown in the city’s Anglophone community—the “Battle of the Hatpins” or la battaille des épingles. In this David-Goliath struggle, Francophone parents, in particular mothers, fought the Government of Ontario in 1916 to have their primary-aged children attending the Guigues School taught in French.

Jean-François began his account by providing useful background on the French presence in Ontario, noting that many Francophone families had moved to Ontario during the late 19th century, especially to the eastern part of the province, including Ottawa. While wanting their children to learn the language of the English majority, Francophone also parents desired that French be the language of instruction in “bilingual schools.”

Under the British North American Act of 1867, the provinces were assigned responsibility for education, with the proviso that they provide separate schools for Roman Catholics outside of Quebec, and for Protestants in Quebec. Using its constitutional authority, the Ontario Government, under pressure from those worried about the growing French presence in the Province, introduced Regulation 17 in 1912 which forbade the use of French as the language of instruction beyond Grade 2.

This sparked outrage amongst Ontario’s Francophone community, leading to, among other things, the birth of an Ottawa newspaper Le Droit that committed itself to the struggle for linguistic rights.

Jean-François explained the divisions within Ottawa’s Roman Catholic School Board between its French-speaking and English-speaking members over the issue, and how various schools responded both in Ottawa and in other parts of the Province to Regulation 17—a combination of obedience, non-compliance, and defiance.

The issue came to a head in January 1916 at the Guigues School when parents, mainly mothers, escorted two sisters, Béatrice and Diane Desloges, into the school to teach their children in French. This brought the parents into direct confrontation with the police and the government-appointed school board who were determined to block their entry and their occupation of the school. Jean-François noted that the extent to which the mothers used their hatpins to fend off the police is unclear. News reports said that in the Battle of the Hatpins, one constable had his thumb bitten, while another received a black eye.

In the end, calmer heads prevailed, with the issue going all the way to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London to be settled. While the Privy Council ruled in favour of the Ontario Government in its use of English as the language of instruction in “bilingual schools,” it ruled against the government in its treatment of Ottawa’s French-led, Roman Catholic School Board.

French continued to be used at Guigues School as a language of instruction, with the Ontario Government losing its appetite for this divisive language battle in the midst of World War I. In the late 1920s, Ontario stopped trying to enforce Regulation 17, but it remained on the statute books until 1944.

In 2016, Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne apologized to the province’s Francophone community.

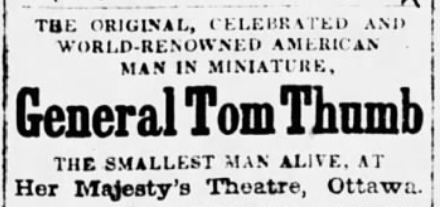

General Tom Thumb and Countess Magri

4 October 1861

The first, global, celebrity entertainer was the dwarf General Tom Thumb, a.k.a. Charles Stratton. Born in 1838 in Bridgeport Connecticut, Stratton was discovered at age four by Phineas Taylor (P.T.) Barnum, the future circus impresario and then owner of Barnum’s American Museum. At only twenty-five inches tall, the child, who reportedly had weighed a hefty 9 ½ pounds at birth, had not grown since he was six months old. Barnum, always on the look-out for the odd and the unusual for display in his museum, which was a mixture of a menagerie, theatre, lecture hall, and sideshow, had stumbled upon a winner. The child was quickly signed to a contract and taught to dance and sing. Little Charles put on his first performance at the American Museum at the age of five though billed as an eleven-year old. His stage name was General Tom Thumb after the fairy tale character of the same name. Precocious and talented, Stratton was an instant hit. Barnum made a fortune as New Yorkers flooded into his museum to see General Tom Thumb.

“General Tom Thumb” dressed as a Scottish clan chieftain, c. 1861, author unknown, Wikipedia.After wowing New York audiences, Barnum took him and his parents to London, the centre of the world in the nineteenth century. His London debut occurred in February 1844 at the Princess Theatre in London. Following a performance of the comic opera Don Pasquale, Stratton came on the stage singing Yankee Doodle Dandy. He later entertained the audience dressed as Napoleon and performed in a number of “tableaux” as Hercules, Ajax and Sampson. But the act loved best by the crowd was his performance as Cupid, complete with little wings.

“General Tom Thumb” dressed as a Scottish clan chieftain, c. 1861, author unknown, Wikipedia.After wowing New York audiences, Barnum took him and his parents to London, the centre of the world in the nineteenth century. His London debut occurred in February 1844 at the Princess Theatre in London. Following a performance of the comic opera Don Pasquale, Stratton came on the stage singing Yankee Doodle Dandy. He later entertained the audience dressed as Napoleon and performed in a number of “tableaux” as Hercules, Ajax and Sampson. But the act loved best by the crowd was his performance as Cupid, complete with little wings.

His reception was not quite up to the adulation received earlier in New York. But that was soon rectified following multiple audiences with Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their family, including the three-year old Prince of Wales. It seems Stratton became a hit after he pretended to fend off one of the Queen’s barking spaniels with his miniature sword. Performances throughout Britain were followed by a tour of continental Europe.

General Tom Thumb first ventured northward to Canada in 1861. It was a good time to perform outside of the United States; the U.S. Civil War had begun in April of that year. At the beginning of October, the troupe came to Ottawa, staying at Campbell’s Hotel, which would be purchased by M. Gouin two years later and renamed the Russell House Hotel.

General Tom Thumb was in town for a two-day gig at Her Majesty’s Theatre located on Wellington Street just west of Bank Street. There were two performances on each of the 4th and 5th of October 1861. Ticket prices ranged from 10 cents for children under ten to 25 cents. Reserved seats were 25 cents each. School groups were admitted “on liberal terms.” Along side General Tom Thumb were the English comic actor and baritone, Mr. W. Tomlin, the American tenor, Mr. W. DeVere, and the pianist Mr. P.S. Caswell. On display at the theatre were the gifts Stratton had received from royalty during his European tours. Interestingly, the advertisement in the Ottawa Daily Citizen warned people to beware of a General Tom Thumb impersonator who worked for Robinson & Company’s circus.

Advertisement that appeared in the Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1 October 1861.The spectacle began before the actual theatre performance, with General Tom Thumb driven from Campbell’s Hotel to HM Theatre in a miniature carriage drawn by “Lilliputian” horses. He was also “attended by Elfin coachmen and footmen.” The reporter who covered the event for the Ottawa Daily Citizen described Thumb as multo in parvo—a great deal in a small space. He opined that Stratton had “fully carried out the universal reputation he has acquired.” He praised the performers acting, singing and dancing abilities, and specifically singled out Stratton’s self-possession as an actor and a readiness of wit. He also had “perfect manners and form.”

Advertisement that appeared in the Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1 October 1861.The spectacle began before the actual theatre performance, with General Tom Thumb driven from Campbell’s Hotel to HM Theatre in a miniature carriage drawn by “Lilliputian” horses. He was also “attended by Elfin coachmen and footmen.” The reporter who covered the event for the Ottawa Daily Citizen described Thumb as multo in parvo—a great deal in a small space. He opined that Stratton had “fully carried out the universal reputation he has acquired.” He praised the performers acting, singing and dancing abilities, and specifically singled out Stratton’s self-possession as an actor and a readiness of wit. He also had “perfect manners and form.”

There still appeared, however, to be some doubt in the reporter’s mind of whether he had watched a performance of the genuine General Tom Thumb. He added that “there was every reason to believe that this one is the ‘original’ Tom Thumb, but whether or not, both he and his ‘aides’ perform a perfect array of rational and attractive entertainment.”

General Tom Thumb returned to Ottawa three more times, in 1864, 1876 and lastly in 1883. On all three occasions he was accompanied by his wife Lavinia who he had married in 1863. The 1864 performance included members of their wedding party—Commodore Nutt, also referred to as the $30,000 Nutt in reference to the value of his three-year contract with P.T. Barnum, and Lavinia’s sister, Minnie Warren. The notice for their show advertised that the “four smallest human beings of mature age” weighed a collective 100 pounds. For part of their 1864 performance, General and Mrs. Thumb wore their wedding costumes. The couple danced and sang. General Thumb also dressed up as Napoleon and a Scottish clan chieftain. Commodore Nutt appeared as a drummer and a sailor with a hornpipe. As with Thumb’s 1861 shows, on exhibit at the HM Theatre were the jewels and other gifts that he had received on his European tours.

The Fairy Wedding, Souvenir Photograph, 1863, Commodore Nutt, General Tom Thumb, Mrs. Tom Thumb, and Minnie Warren (left to right). By this point, the General has already grown a bit. Author Mathew Brady, Wikipedia.

The Fairy Wedding, Souvenir Photograph, 1863, Commodore Nutt, General Tom Thumb, Mrs. Tom Thumb, and Minnie Warren (left to right). By this point, the General has already grown a bit. Author Mathew Brady, Wikipedia.

In 1876, General and Mrs. Tom Thumb performed over two days at Gowan’s Opera House. Their act was much the same as that of their previous trip to Ottawa, but this time they were supported by Major Edward Newell, another dwarf under contract with Barnum. Newell was the husband of Minnie Warren, Mrs. Tom Thumb’s sister. Minnie was sadly to die in childbirth two years later.

General and Mrs. Tom Thumb’s 1883 Ottawa performances took place in May of that year, with shows at the Grand Opera House. By this point, the General had actually grown to a still tiny 2 feet 11 inches. He had also grown stouter. The Ottawa Daily Citizen commented that both he and Lavinia were “getting on in years.” Still, the General’s act was described as very amusing. Mrs. Stratton was described as “as charming as ever.” Along with the General and his wife, other members of their troupe included dancers, a ventriloquist and a lady whose odd act consisted of “highly educated, trained canaries.” What these canaries did was unfortunately not reported.