James Powell

Lotta and the USC Canada

10 June 1945

For older Canadians, Lotta Hitschmanova needs no introduction. Each year, until the early 1980s, her distinctive voice would be heard on the radio and television urging people to give generously to the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada (USC) located at 56 Sparks Street, Ottawa. She had established the Committee in 1945 to help the poor and suffering, especially children, in war ravaged Europe. Later, the USC shifted its attention to developing countries. Always dressed in a quasi-military, olive-green uniform complete with hat, maple leaf badges, and a chest full of medal ribbons received from grateful nations, Lotta was one of Canada’s most recognizable personalities. Overseas, she became the face of Canadian humanitarian efforts, always present where the need was greatest.

Lotta’s story began in Prague, in what is now the Czech Republic. Born into a loving family on 28 November 1909, her father was Max Hitschmann, a prosperous industrialist, and her mother Else, a prominent socialite. Lotta received a first class education, studying at the University of Prague and the Sorbonne in Paris. In addition to a PhD in philosophy, she received diplomas in five languages, English, French, German, Spanish and her native Czech, as well as one for journalism. Somehow, she also found time to earn a Red Cross nursing certificate. In the late 1930s, she became a journalist for Czech and other eastern European newspapers, earning a reputation for being an outspoken opponent of Nazi Germany.

Her comfortable life was shattered when the Nazis marched into Czechoslovakia following the Munich Agreement between the major European powers and Adolf Hitler. She was forced to flee for her life, leaving all she knew behind. She was never to see her parents again; they were to die in a German concentration camp. Her sister and brother-in-law fled to Palestine; years later they joined Lotta in Canada.

Almost penniless, Lotta first went to Paris and then to Brussels, where she resumed her journalism career before having to flee once more when Germany invaded Belgium in 1940. It was about this time that she began to go by “Hitschmanova,” the Slavic version of her name, instead of the Germanic “Hitschmann” as a personal response to Nazi aggression in Europe. Escaping to the south of France, she settled down to a precarious life in Vichy-controlled Marseilles, working for an aid agency as an interpreter. This is where she first came into contact with the Unitarian Service Committee, a Boston-based relief agency that ran a medical clinic in the city. Refused a visa to immigrate to the United States, she was later granted a visa “for the duration,” by the Canadian government at the request of the Czech government in exile in London. She arrived in Montreal in July 1942, having crossed the perilous, submarine infested Atlantic by boat, travelling via Spain, Portugal, Bermuda, and New York.

She almost immediately found a job as a secretary for a lumber company owned by a Czech family who knew her parents. Three months later, she got a job as a postal censor in Ottawa, working out of a temporary, wooden, war-time building at Dow’s Lake. She also used her journalist skills, writing for the Ottawa Citizen, and talking about Czechoslovakia on the local French-language radio station. In 1944, she temporarily moved to Washington D.C. to work with the refugee relief organization of the newly formed United Nations. But upset with how the agency operated, and concerned that she might not be able to stay in the United States or Canada after the war, she returned to her censor’s job in Ottawa.

On 10 June 1945, Lotta chaired in Ottawa the first meeting of the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada with the encouragement of the Boston-based parent organization. Four persons from the parish of the Ottawa Unitarian Association, whose church was then located at the corner of Elgin and Lewis Streets, attended this inaugural meeting. Lotta’s subsequent task was to contact the five other Unitarian churches in Canada to get their support. At the Committee’s second meeting, it was agreed that the purpose of the organization was to provide relief to distressed people, especially children, of Czechoslovakia and France. Encountering difficulty in registering with the government, Cairine Wilson, Canada’s first woman senator, was invited on board in the role of honourary chairperson, giving the fledgling agency political clout. Two months later, the Committee was registered under the War Charities Act as “The Unitarian Service Committee of Canada Fund.”

USC Canada Fundraising Advertisement,

USC Canada Fundraising Advertisement,

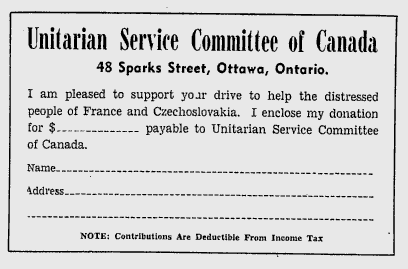

The Evening Citizen, 14 April 1947Initially, the USC operated out of Lotta’s home at 668 Cooper Street, before moving into larger premises, first at 48 Sparks Street, then down the street to 78 Sparks, and finally, in the mid-1950s, to its quarters at 56 Sparks Street—which was to become one of Canada’s best-known addresses. During its first year of operation, volunteers, mostly women, collected and packed 30,000 kilograms of used clothing in 150-pound, wooden crates destined for destitute French and Czech children. Shipping was provided free by Canadian Pacific Railway within Canada, and by a French aid agency from Canada to Paris. Also sent were medical supplies, “utility kits” consisting of toiletries and educational supplies for children, dried milk, and food. Among the USC’s first projects was a home for physically handicapped children in France, many of whom had lost limbs in Allied air raids. Later projects included apprenticeship programmes, the provision of artificial limbs to youngsters, and a foster-parents scheme where Canadians could sponsor a child for three months for $45.

That first year of operation also saw Lotta becoming a Canadian landed immigrant, giving her the security of a permanent homeland. She also began to travel extensively in Canada, meeting with service organizations and churches, and providing press interviews to spread the word about the extent of the misery in Europe, and what Canadians could do to help through the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada. In 1945, the Committee raised $64,000, equivalent to almost $900,000 in today’s money. The following year, it raised $180,000 in money and gifts-in-kind, equivalent to roughly $2.5 million today. It was about this time that Lotta adopted her military-style costume, which was based on a U.S. army nurse’s uniform. In addition to being practical, it identified the USC, and gave her an air of authority.

The establishment of the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada redeemed a pledge Lotta made to herself when she arrived in Canada that she would give back to society, and to the nation that had given her a new home. Initially, she thought that her work would last only a couple years. However, that naïve view was quickly dashed; there was always new crises and new needs. As the USC’s programmes in Czechoslovakia and France wound down, the Committee shifted its attention to southern Europe, including Italy and, most importantly, Greece which in 1950 was emerging out of a bitter civil war. Campaigns were organized, including “Bread for Greece,” the “March of Diapers,” and “Houses for Greece.” While broader community needs were not overlooked, children were always the focus of the USC’s activities. As Europe got back on its feet through the 1950s, the USC of Canada gradually moved its operations to areas of greater need including Korea, India, the Gaza Strip, Bangladesh, Hong Kong, Indonesia, and southern Africa.

Sample Registration Card of a Child War Victim and case history that would be forwarded by the USC Canada to a Canadian “foster family.”

Sample Registration Card of a Child War Victim and case history that would be forwarded by the USC Canada to a Canadian “foster family.”

The Evening Citizen, 14 April 1947.

At all times, the Unitarian Service Committee’s aid programmes were founded on the basis of caring for fellow human beings, respect, and partnership. Projects were run locally, with donors and aid recipients equally responsible for success. USC involvement was also expected to wind down over time, with aid recipients becoming self-reliant, taking over the project themselves.

While the Unitarian Service Committee of Canada had its roots in the Unitarian Church, and many of its members were Unitarian, it was a distinct, non-political, non-sectarian body separate from both its Boston parent organization as well as the Canadian Unitarian Association. It did not proselytize, nor did it discriminate. Assistance was provided without regard to race, origin, or religion. Overtime, the Unitarian Service Committee became better known by its alternate name, USC Canada.

Through the decades that followed, Lotta Hitschmanova worked tirelessly, rising as early as 5am after putting an eighteen-hour day. She expected her staff to do likewise. She apparently preferred to hire middle-aged women with no children since they would be less distracted by outside activities, and able to devote themselves fully to the cause. She also stressed frugality; stretching the dollar was important, both as a way of providing more for her children abroad, and keeping donors happy. Despite being a harsh taskmaster on herself and staff, Lotta was much loved at home and abroad. Her success could be measured by the ribbons of honour which she proudly wore on the breast pocket of her uniform. These included the Order of Canada, first as Officer and later as Companion, the Canadian Centennial Medal, the Queen Elizabeth Silver Jubilee Medal, the Order of Civil Merit from Korea, la Médaille de la Réconnaissance française, la Médaille d’Honneur de la Croix Rouge, the Decoration of Honour and Peace from the Netherlands, the Red Cross Decoration and the Athena Messolora Gold Medal from Greece, and the Meritorious Order of Mohlomi from Lesotho.

In 1982, Lotta Hitschmanova, suffering from the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, retired as Executive Director of the USC Canada. She died in Ottawa on 1 August 1990. But her work lives on. The USC Canada, which is still based at 56 Sparks Street, remains active in developing countries around the world. Today, with an annual budget of about $6 million, its core focus is food production, biodiversity and health eco-systems, implemented through its “Seeds for Survival” programme funded in part by the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development as well as thousands of individual donors. Faithful to the approach taken by Lotta, assistance the USC Canada programme supports women and young farmers through training, enabling them to live independent and secure lives in an ecologically sustainable manner. Lotta would have been proud.

Sources:

Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, 2015. Lotta Hitschmanova’s Uniform, http://www.pier21.ca/blog/dconlin/lotta-hitschmanova-s-uniform.

History Lives Here Inc., 2004-15. Soldier of Peace Documentary, http://historyliveshere.ca/projects/soldier-of-peace-documentary/.

The Evening Citizen, 1946. “Nobody’s Children?” 1 April.

————————, 1946. “Unitarian Committee Ships More Clothing,” 1 April.

———————-, 1946. “Canada Aids Ill-Clad War-Shocked Children,” 20 September.

The Montreal Gazette, 1947. “Unitarian Group Begins Campaign,” 27 January.

Sanger, Clyde, 1986. Lotta, Stoddart Publishing Co.: Toronto.

USC Canada, 2015. http://usc-canada.org/.

Images:

Lotta Hitschmanova, USC Canada, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lotta_Hitschmanova.

USC Fundraising Advertisement, The Evening Citizen, 14 April 1947.

Sample Registration Card of a Child War Victim, The Evening Citizen, 14 April 1947.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Queen's Plate

31 May 1872

The most famous and prestigious thoroughbred horse race in Canada is the Queen’s Plate, open to Canadian-bred, three-year-old horses. It’s also the oldest continuously-run horse race in North America, dating back to 1860, seven years before first running of the Belmont Stakes, the oldest of the “Triple Crown” races in the United States. Over its illustrious history, many members of the Royal family have attended this storied event from Princess Louise in 1881, to the Queen Mother in 1965, and to Queen Elizabeth in 1959, 1973, 1997 and, most recently, 2010. Horse racing is indeed the “sport of kings!”

Advertisement for the 1872 running of the Queen’s Plate, Ottawa Daily Citizen.

Advertisement for the 1872 running of the Queen’s Plate, Ottawa Daily Citizen.

The story of the Queen’s Plate begins in 1859 when Sir Casimir Gzowski, the president of the Toronto Turf Club, petitioned the Governor General for an annual horse racing prize to be awarded by Queen Victoria to horses bred and reared in Upper Canada (Ontario). He correctly believed that the cachet of winning a royal prize would encourage the development of horse breeding in Canada. Queen Victoria graciously agreed to the request providing an annual prize of 50 guineas for a race to be called the Queen’s Plate. (A guinea is defunct British gold coin no longer minted by the mid nineteenth century but widely used as a unit of account in horse racing, the art world, and certain professions well into the twentieth century. It had a value of 21 shillings sterling.)

The Royal Privy Purse continues to provide this annual prize though instead of 50 guineas, it reportedly sends a bank draft for the sterling equivalent except when a member of the Royal Family is present for the race. Then, the winner receives 50 gold sovereigns in a purple bag. The winner also receives 60 per cent of the race purse of $1 million. Confusingly, the “Plate” is a foot-high golden cup on a black base rather than a plate. (The traditional royal prize for a horse race had been a silver plate, hence the name. However, over time the nature of the prize changed but the name stuck.)

The first running of the Queen’s Plate took place at the end of June in 1860 at the Carleton Race Course in Toronto. It was open to all horses reared in Upper Canada which had never won public money. During the early years of the Queen’s Plate, horses competed in three heats rather than a single race as is the case today. The first winner was a five-year old horse by the name of Don Juan, owned by a Mr. White and ridden by Charles Littlefield. Don Juan came in second in the first heat, but won the second and third heats of the competition over a one-mile track with his best time of 1 minute 58 seconds.

Although the next several Queen’s Plates were held at the Carleton Race Course, it subsequently moved around the province depending on the lobbying powers of various racing clubs and politicians before it settled down for good at the Woodbine Race Course in Toronto in 1883. Until 1956, the race was held at the old Woodbine site at the end of Woodbine Street in Toronto close to Lake Ontario. It then moved to the current Woodbine location on Rexdale Boulevard, north of the Pearson Airport in Etobicoke. During the Queen’s Plate’s journey around Ontario, the race came to Ottawa on two occasions, the first in 1872 and the second in 1880.

The organization that brought the Queen’s Plate to Ottawa in 1872 was the Ottawa Turf Club, founded in 1869 with the patronage of Sir John Young, later known as Lord Lisgar, the Governor General, who was an avid horseman. The President of the Club was Joseph Aumond, Vice-President was Nicholas Sparks, and Edward Barber was the Secretary. While the lobbying of Sir John A. Macdonald, the Premier, may have helped the new Ottawa Turf Club win the event, Lord Lisgar was likely the one most responsible for bringing the race to Ottawa. With His Excellency as its patron, the Ottawa Turf Club definitely had the inside track for hosting the event. News that the Queen’s Plate had been conferred on Ottawa was officially relayed to the Ottawa Turf Club in February 1872, with the race planned for late spring. The conditions of the race were: “For horses, geldings or mares, bred, raised, trained and owned, in the Province of Ontario, who have not previously won public money at any race meeting. The whole stake to go to the winner.”

The Club organized a two-day racing extravaganza for Friday and Saturday, the 31th of May and the 1st of June, 1872. The event was held at the new Mutchmor Driving Park which had opened the previous year. The race track and the adjoining Turf Hotel were owned by Ralph Muchmor and Edward Barber, the Turf Club’s Secretary. Total prize money for the two-day event amounted to $2,850—a fair sum in those days.

Long before race time, pedestrians and carriages packed Bank Street, all heading for the race track located now where the Mutchmor Public School is today. Race conditions were perfect with the track having just been rolled after a recent rain. The main attraction of the day was, of course, the Queen’s Plate, the third race of the afternoon. By the time Lord and Lady Lisgar arrived at 3 pm, every vantage point was taken up, the stands filled to capacity with ladies and gentlemen, while less fortunate punters made do with fence tops, and the seats of cabs and wagons. According to the Ottawa Daily Citizen, it was difficult to estimate the size of the crowd, but the stands scarcely accommodated a quarter of the numbers. Many of the visitors came from other parts of Canada and even from the United States to witness the Queen’s Plate which was already the highlight of the Canadian racing calendar.

The first race of the day was the $300 Hurdles Race, a two-mile run with eight hurdles 3’ 6” high, which was won by Duffy by three lengths. The second race was the $100 Steward’s Race won by Mohawk who took both heats. Up next was the Queen’s Plate. The prize was 50 guineas ($256), the gift of “Her Most Gracious Majesty.” The winning horse may have received an additional purse but the report relating to this was obscurely written. It read: “T.C.W. Entrance, $10 p.p. to go with the plate.”[1] The Ottawa Turf Club provided $100 to the second-place horse.

Six horses were entered in the 1½ mile race (no heats): Blacksmith, a 4-year old, black horse, with its jockey wearing a black jacket and blue cap; Fearnaught, a bay horse with its jockey in scarlet with a dove colour cap; Alzora, a chestnut mare, whose jockey wore brown and white; Jack Vandall, a bay gelding, its jockey in blue and white; Bay Boston, a 5-year old, bay horse, (colours not identified), and Halton, a 5-year old bay horse whose jockey wore scarlet. Halton was the favourite. Three of the horses in the running, Fearnaught, Alzora and Jack Vandall, had the same sire, Jack the Barber, a celebrated thoroughbred horse originally from Kentucky.

The Trophy awarded for winning the Queen’s Plate. Canadian Museum of History.

The Trophy awarded for winning the Queen’s Plate. Canadian Museum of History.

At post time, there were four false starts. But after they were finally off, it was deemed a “splendid race.” After the first half mile, it became apparent that the race belonged to Fearnaught, with the favourite, Halton, fading. In a time of 2 minutes 54 ½ seconds, Fearnaugh, ridden by Richard Leary and owned by Alexander Simpson, won the 13th running of the Queen’s Plate. Jack Vandall came in second and Halton third. Richard Leary, the winning jockey who was also a resident of Ottawa and the horse’s trainer, was presented with a gold-mounted riding whip by Mr. William Young of the firm Young & Radford, a watchmaker and jewellery manufacturer located at 30 Sparks Street.

Two more races followed the Queen’s Plate to round out the racing for the afternoon. These were the $300 Tally Ho! Stakes and the $150 Memorial Plate.

Betting had been fierce in the lead-up to all the races. But all the favourites came up short that day causing “a monetary twinge among the sporting fraternity,” according to the Ottawa Citizen.

Pelting rain almost caused the postponement of the second day of racing from the Saturday to the following Monday. Racing on a Sunday, the Sabbath, was forbidden. However, as many of the horses were slatted to race in Montreal the following week, the decision was made to go ahead on the principle “run, rain or shine.” Fortunately, at race time the clouds cleared, though attendance suffered. Four more races were held: the $600 Carleton Plate; the $400 Lumbermen’s Purse; the $300 Merchants’ Plate; and, finally, the $150 Consolation Stakes. There was a bit of excitement surrounding the running of the Lumbermen’s Purse. Owing to “a misunderstanding or improper interference,” the race had to be run twice. People almost came to blows before the Club Secretary announced that all pools and bets were off for the race.

The Ottawa Turf Club, the host of the 1872 Queen’s Plate, disappeared from the Ottawa racing news in the decade following its big race weekend but not before becoming mired in controversy. At the end of a racing fixture held in October 1874, the Club held a “deer hunt” as a grande finale to the day’s events. A half-starved deer was released onto the field. It was barely able to run having been cooped up in a small cage, its joints stiffened from lack of use. Instead of taking off into the nearby bush to be hunted by a pack of dogs followed by riders, it stumbled into the crowd. It only took ten seconds for it to be taken down and torn to pieces by the hunting dogs amidst the spectators’ carriages. The Ottawa Daily Citizen thought that this was a case for the S.P.C.A. and “hoped that the people of Ottawa will never be asked to patronize such a “sport” again.”

The Ottawa Racing Association hosted the 21st running of the Queen’s Plate at the end of June 1880. It was the second race of the first day of racing entertainment again held at the Mutchmor track. Five horses were at the post come race time; a sixth, the mare Footstep, had been pulled on a challenge on the grounds of ineligibility since it had not been trained in Ontario. The winner was Bonnie Bird, owned by John Forbes and ridden by Richard Leary, the same jockey who rode to victory in the 1872 Queen’s Plate. Bonnie Bird also ran he following day in the first Dominion Day Derby carrying five pounds extra owing to having been the Queen’s Plate winner. Owing to a very bad send off, Bonnie Bird was virtually out of the race at the start but Richard Leary, the jockey, somehow manage to close the gap with the leaders on the turn but was unable to catch Lord Dufferin who won by a length.

Today, Ottawa horse-racing fans can enjoy standard-bred harness racing at the Rideau Carleton Raceway on the Albion Road. But if you want to dress up, wear a fascinator, and otherwise enjoy the excitement of the annual running of the Queen’s Plate, you will need to head to the Woodbine Race Track in Toronto.

Sources:

Anderson-Labarge, 2015. “Canada History Week: Spotlight on Sports (Part 2),” Canadian Museum of History, https://www.historymuseum.ca/blog/canada-history-week-spotlight-on-sports-part-2/.

Buffalo Commercial, 1861, “Great Race at Detroit,” 10 July.

Daily Citizen, 1872. “The Queen’s Plate,” 16 February.

—————–, 1872. “Ottawa Turf Club Races,” 31 May.

—————–, 1872. “Ottawa Turf Club,” 1 June.

—————–, 1872. “Ottawa Turf Club,” 3 June.

—————–, 1880. “Mutchmor Park,” 2 July 1880.

Dulay, Cindy Pierson, 2018. “2010 Queen’s Plate Royal Visit,” Horse-Races.Net, http://www.horse-races.net/library/qp10-royal.htm.

Rideau Carleton Raceway, 2019. https://rcr.net/.

Smith, Beverley, 2018. “Horse Racing: Queen’s Plate,” Globe and Mail, 17 April.

Wencer, David. 2019. “Toronto’s Horse Racing History,” Heritage Toronto, http://heritagetoronto.org/torontos-horse-racing-history/.

Woodbine, 2019. Queen’s Plate 2019, https://woodbine.com/queensplate/.

Wikipedia, 2019. Queen’s Plate, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen%27s_Plate.

[1]This cryptic phrase likely means that the Queen’s Plate was an entry in the Triple Crown Winner series and that the $10 per entry free was included in the prize.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Lover's Walk

14 May 1938

When visitors come to Ottawa, they naturally gravitate to Parliament Hill to view the magnificent neo-Gothic Parliament Buildings, to stroll in the surrounding gardens where statues and memorials to Canadian sovereigns and statesmen abound and, of course, to take in the stunning views across the Ottawa River towards Hull and the Gatineau Hills. One hundred years ago, the number two Ottawa tourist destination was Lovers’ Walk—a pathway that wended its way around the Parliament Hill bluff roughly half-way up the escarpment. Surrounded by a hardwood forest and flowering shrubs, including lilacs and honeysuckle, the pathway commanded splendid views of the Ottawa River, with benches for the weary or for the amorous. Visitors to this tranquil wilderness could easily forget that they were in the heart of Canada’s capital city. According to a 1920s’ guide book, anyone who has not taken a stroll there “has not seen all the charms of the capital. In fact, he has missed one of the greatest of them.” Fast forward to today, you would be hard pressed to find an Ottawa resident who has any knowledge about this once-famous pathway.

The history of Lovers’ Walk apparently dates back long before the arrival of the first Europeans to the Ottawa Valley. Accounts say that the pathway was used by Canada’s native peoples travelling along the southern banks of the Ottawa River. During the first half of the nineteenth century, raftsmen took this same route as a short cut moving to and from their homes in Lower Bytown and the timber chutes at the Chaudière Falls. Sometime after Confederation in 1867, the rough path was widened, decorative iron railings were fitted to protect users from falling, and staircases were installed at several points to give the general public ready access.

One story says that William Macdougall, the Minister of Public Works from 1867-69 in Sir John A. Macdonald’s first Dominion government, was responsible for upgrading the trail from a rough, dangerous track to a gentle path that even women dressed in the long gowns of the period could stroll along without fear of tripping. Macdougall, who was apparently a “hands on” type of Minister, stumbled upon the footpath when he was inspecting the construction of a ventilation shaft for the Centre Block on Parliament Hill.

Another story gives the credit for Lovers’ Walk to Thomas Seaton Scott, the Dominion Chief Architect from 1872-1881. Seaton was responsible for laying out the structured gardens that surround the Parliament Buildings as well as designing the Drill Hall on Elgin Street. According to this account, Seaton constructed the steps down from the formal gardens on top of Parliament Hill to allow the general public access to the wilder charms of the pathway.

Who actually came up with the name Lovers’ Walk is unknown. The first newspaper reference to this name appears in the Ottawa Daily Citizen in 1873. A visitor at about this time said that “no more appropriate name could be devised.”

Steps down to Lovers’ Lane, Parliament Hill, Dept of the Interior, Library and Archives Canada, PA-034227, circa 1920s.

Steps down to Lovers’ Lane, Parliament Hill, Dept of the Interior, Library and Archives Canada, PA-034227, circa 1920s.

In addition to tourists and Ottawa residents, the denizens of Parliament on top of the bluff also took advantage of the pathway, seduced by Lovers’ Walk’s winsome charms. Prime Ministers, Cabinet Ministers, Senators and ordinary Members of Parliament were all known to take breaks from the hard work of politicking to refresh themselves with a stroll through its sylvan beauty. Lovers’ Walk also attracted bird watchers. One avid amateur naturalist in the early 1930s spotted 59 different species from the pathway.

Lovers’ Walk could be accessed from either side of the Parliament Buildings. On the eastern side, there was a flight of stairs leading from roughly where the equestrian statue of Queen Elizabeth stands today. Another flight of stairs started from a location behind the Bytown Museum close to the locks on the Rideau Canal. On the western side of Parliament Hill at the end of Bank Street, behind the old Supreme Court of Canada, which was demolished in 1956, strollers entered the Walk through a stone gateway. Midway on the path there was a lookout with benches for those wanting to stop to rest or admire the views. There was also a lion-headed water fountain to refresh the thirsty. Unfortunately, strollers and lovers sometimes came across less-savoury elements who also frequented Lovers’ Walk. In 1875, there was a call for police to exclude “roughs” who amused themselves by throwing burrs onto ladies’ dresses. It was also advisable not to pick the flowers. In 1931, Mrs Pamela Cummings of 726 Cooper Street was fined $3 plus $2 court costs for stealing lilacs.

Lovers’ Walk was closed in the winter owing to snow and ice that made walking dangerous, but re-opened each spring, typically in May, once conditions were suitable. Given the steep nature of the hillside, there were frequent rockslides that were dealt with by the Department of Public Works. At the start of the First World War, the pathway was closed to the public and was patrolled by the Dominion Police. The authorities feared that German saboteurs could use Lovers’ Walk to access the ventilation shafts that aired the Centre Block. By cutting the iron protective grills, saboteurs could potentially plant explosives under the building and blow up Parliament. These precautions were discontinued after the Centre Block was destroyed by fire in February 1916.

By the 1930s, Lovers’ Walk was becoming less popular. With the Depression at its peak, the pathway had become the haunt of panhandlers and the homeless, and was considered unsafe for casual strollers. The Ottawa Journal reported that “the dregs of humanity would pan handle the lovers, even seek to molest them.” A “jungle” of tin-patched shacks built by homeless men sprung near the path close to the western entrance. The eastern end, close to the Canal locks, was described as the haunt of drunks whose wild shouts could be heard from men drinking denatured alcohol. Regular police patrols and RCMP efforts to dismantle the shacks did little. There were also dark allegations of immorality.

In the winter of 1937-38, two landslides washed out more than sixty feet of Lovers’ Walk. It never officially re-opened. On 14 May 1938, the Ottawa Citizen reported that to repair the pathway would cost over $30,000. Although the Senate Standing Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, chaired by Cairine Wilson, recommended that the Department of Public Works take steps to stabilize the cliff face and reopen Lovers’ Walk, the repairs were not undertaken. During a time of depressed economic conditions, $30,000 was simply too much.

Besides landslides and the presence of “undesirables,” another possible factor behind the closure of Lovers’ Walk was concerns about Government liability. In 1933, a young boy had climbed over a gate when Lovers’ Walk was closed for the winter. He slipped on the ice, fell 50 feet, and was lucky to get away with only a broken femur. His father unsuccessfully tried to sue the government for his doctor’s bill. In 1937, a man, who had been sitting on a guard railing, broke his spine when he lost his balance and plunged down the cliff.

Some say that it was Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King who ordered the closure of Lovers’ Walk. However, another account says that King had wanted to keep it open and that it was only following extensive discussions with the RCMP, Public Works, and the Speakers of both the Senate and the House of Commons that the decision to close it was reluctantly taken. High barricades were installed at both ends to stop people from using the path now deemed unsafe.

By the 1950s, Lovers’ Walk was a “desolate ruin of crumbling masonry, rusted and broken iron guardrails and rotten wooden shoring.” What was left of the pathway was overgrown and narrowed by erosion. Empty bottles, and other refuse littered the place—evidence that the deteriorating ruins of Lovers’ Walk remained a refuge for the homeless sleeping rough during the summer months. After an intoxicated painter fell to his death in 1960, a coroner’s jury recommended that what was left of the pathway be destroyed to ensure public safety.

Nothing was done. The area got a fearsome reputation, especially at night. By the late 1960s, secretaries and clerical staff working late on Parliament Hill were fearful of using the stairs, which cross Lovers’ Walk, to get to the parking area known as “the Pit,” despite, according to the Ottawa Journal, “routine flushing out by the RCMP foot patrols of winos, ‘rub-a-dubs,’ vagrants and, more recently, hippies from their dormitory-pad along Lovers’ Walk.” In July 1968, ex-MP Herman Laverdière was stabbed and robbed by hooligans when he went to investigate a scream that had emanated from the wooded area after he left his office at 11 pm.

Notwithstanding the increasingly bad press, there were attempts during the 1960s to restore Lovers’ Walk to its former glory. Members of all major parties championed the pathway at various times. But with the price tag rising steadily, the government in power always demurred owing to the difficulty in controlling erosion on the escarpment. In the 1980s, when Jean Pigott was Chair of the National Capital Commission, there was another look at restoring the pathway. Again, it was deemed too expensive. In 2000, the Department of Public Works looked at rebuilding the pathway given the historic nature of Lovers’ Walk and the magnificent views of the Ottawa River. Again, the issue was put on the back burner.

Most recently, LANDinc was commissioned by Public Works to develop a strategy “to restore and reforest the slopes [of Parliament Hill] to ensure long-term sustainability.” Over time, invasive species, including the lilacs, would be removed and replaced by endemic shrubs and trees. In 2014, Graebeck Construction won a $4.78 million contract to rehabilitate the western slope of Parliament Hill and the perimeter wall. There was, however, no mention of re-opening Lovers’ Walk to the general public.

Sources:

Capital Gems, 2018, Lover’s Walk Ruins, http://www.capitalgems.ca/lovers-walk-ruins.html.

Canada, 1938. Senate Journals, 18th Parliament, 3nd Session, Vol. 76, p. 344, 24 June.

———-, 1960. House of Commons Debates, 24 Parliament, 3rd Session: Vol. 6, p. 6605-06, 20 July 1960.

LANDinc, 200? Parliament Hill Stabilization,” http://www.landinc.ca/escarpmentwalkway-1.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1873. “Town Talk,” 7 July

————————-, 1875. “The Parliament Hill,” 20 March.

————————-, 1875. “The Lovers Walk,” 23 August.

————————-, 1926. “Lovers Walk As Seen In Seventies,” 24 December.

————————–, 1933. “Boy Injured On Parliament Hill,” 27 March.

————————-, 1937. “Has Romance Departed From Lovers’ Walk.” 16 January.

————————-, 1937. “When Sturdy Raftsmen Used Lovers’ Walk as Short Cut,” 6 February.

————————-, 1938. “Repair Works on Lovers’ Walk May Cost Over $30,000,” 14 May.

————————-, 1960. “Destroy Lovers’ Walk Jury’s Recommendation,” 20 May.

————————-, 1966. “Lovers find road to romance rocky on Parliament Hill,” 14 May.

————————-, 2000. “Behind the Hill: A Walk into history,” 22 May.

Ottawa Construction News, 2014. Graebeck Construction wins bid for Parliament Hill slope stabilization work, 1 February, https://ottawaconstructionnews.com/local-news/graebeck-construction-wins-bid-for-parliament-hill-slope-stabilization-work/.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1931. “Magistrate Warns Flower-Bed Vandals,” 29 May.

————————–, 1937. “Fear Spine May Be Broken,” 15 June.

————————–, 1938. “Sweethearts Missing Famous Lovers’ Walk,” 18 July.

————————–, 1939. “May Not Re-open Lovers’ Walk,” 26 May.

————————–, 1939. “Remember When?” 8 July.

————————–, 1942. “Lovers’ Walk Ruled ‘Dangerous,’ It Won’t Be Reopened,” 31 July.

————————–, 1968. “Perils of ‘The Pit’ Worry Hill Security Staffs,” 12 July.

Urbsite, 2009. Lovers’ Walk,” http://urbsite.blogspot.com/2009/12/lovers-walk.html, 29 December.

Windsor Star (The), 1952. “Today in Ottawa,” 23 August.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Work or Bread!

5 April 1877

When we think of an economic depression, we usually think of the Great Depression that started in late October 1929 with the New York stock market crash and lasted through the “Dirty Thirties.” But there was another global economic downturn, sometimes called the Long Depression, that started with the Panic of 1873 and lasted until 1896 according to some historians. Like the Great Depression, it resulted from a combination of real, financial and monetary factors. It began in central Europe with a stock market crash in Vienna, then the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The bursting of a speculative bubble revealed overextended financial institutions and stock market manipulation, leading to bank failures and corporate insolvencies. The financial impact rippled across international borders and even the Atlantic. (Sound familiar?) In North America, there had been a huge over-investment in railways—the “dotcom-like” speculative investment of the nineteenth century. Many of the railway companies had raised large sums of money based on unrealistic expectations of future profitability. In September 1873, Jay Cooke & Company, a large U.S. bank and a major investor in railway bonds, failed. This sparked a financial panic in New York. Share prices collapsed. The stock exchange closed for ten days. In the months that followed, dozens of railway companies failed, bringing down financial institutions in their wake.

These developments happened against the backdrop of a global economy undergoing major structural changes. The industrial revolution was in full swing. Germany and the United States were challenging Britain’s economic supremacy. New industries and new production processes were rapidly overturning the old economic order. Productivity was rising and prices for industrial and agricultural goods were falling. While many took advantage of the opportunities being created and prospered, those who were unable to adapt to the rapid changes suffered.

Added to these shocks in North America was the impact of the epizootic of 1872-3—an equine flu that started outside of Toronto and spread across Canada and the United States. While the mortality rate was typically low, few horses outside of certain isolated regions were spared. It took weeks for stricken equines to recover, with crippling consequences for an essentially horse-drawn economy. Even the railways were affected as coal was shipped to rail terminals using horse-drawn wagons.

Governments did little to ease the pain of the downturn in economic activity. The idea of government assistance for the poor was still in the future. With all major countries, including Canada, wed to the gold standard, there was also little scope for monetary action to support economic activity, even if central banks (if countries had them) wanted to do something. Meanwhile, the United States joined gold standard countries in 1873, after having had an un-backed fiat currency since the start of their civil war. It ended the unlimited coinage of silver (the Crime of ’73 according to silver supporters) which might otherwise have led to lower interest rates. Protectionist sentiments rose everywhere. The major countries, with the exception of Britain, adopted high tariffs in an effort to protect domestic industries and jobs. International trade suffered.

Canada was in the thick of all these trends. As is the case today, it was a small economy closely linked to its southern, much larger, neighbour. When the United States entered the Long Depression, so did Canada. To make matters worse, the United States had abrogated its trade reciprocity deal with Canada a few years earlier. Although the reciprocity agreement only covered natural resources, this mattered importantly for Canada.

Hon. Sir Richard Cartwright, 1881 Topley Studio Fonds Library and Archives Canada, PA-025546.In February 1876, Richard Cartwright, the Liberal Minister of Finance, attributed the ongoing depression in Canada to: poor U.S. economic conditions, which were “visibly affecting Canadian interests;” overlarge imports; excessive inventories which were depreciating in value; greedy banks who extended loans “to men of straw, possessing neither brains nor money;” and a depression in the lumber trade owing to “inexperienced operators unable to compete when U.S. prices fall.”

Hon. Sir Richard Cartwright, 1881 Topley Studio Fonds Library and Archives Canada, PA-025546.In February 1876, Richard Cartwright, the Liberal Minister of Finance, attributed the ongoing depression in Canada to: poor U.S. economic conditions, which were “visibly affecting Canadian interests;” overlarge imports; excessive inventories which were depreciating in value; greedy banks who extended loans “to men of straw, possessing neither brains nor money;” and a depression in the lumber trade owing to “inexperienced operators unable to compete when U.S. prices fall.”

To help ameliorate matters, he said that the government was taking advantage of cheap labour and materials to bring forward public works projects. Cartwright, a proponent of free trade, resisted calls for tariffs on manufactured goods beyond those necessary for revenue purposes on the grounds that manufacturing employment accounted for only 40,000 jobs. The government needed to look after the interests of the other 95 per cent of the working population.

In Ottawa, matters came to a head in early 1877. Unemployment, which was always high in winter owing to the seasonality of many jobs, was worse than usual. Each morning, hundreds of unemployed, able-bodied men congregated in the Byward Market looking for an hour or two of work. Times were tough even for those who had jobs. Pay had been reduced from $1.25 per day to a meagre 90 cents per day.

On 5 April 1877, 200-300 unemployed men assembled as usual early in the morning in the Byward Market looking for work. When little was forthcoming, they decided they would do something about their situation. Perhaps the Mayor of Ottawa, William Waller, would be able to able to provide work or bread. The men marched on City Hall on Elgin Street. Unfortunately, the mayor was absent. A messenger was dispatched to find him. Meanwhile a Citizen reporter interviewed some of the men while they waited. Their stories were dire. Many had large families to feed but had been out of work for months. Starvation stared many in the face. Peter Boulez had a family of twelve, but had had no employment since the previous November. With his limited savings exhausted, he needed to find work to put bread on the table. Hans Shourdis had been living off of soup for the past four months, “his stomach a stranger to meat.” Christmas had been his last satisfying meal. A kindly lady had given him charity but that all went to his five children.

When Mayor Waller appeared, he said that he deeply sympathized with the workmen. However, he reminded them that the depression was being felt across the country, and opined that the Dominion government was not responsible for the hard times. He announced that City Council would be meeting on the following Monday to discuss a drainage scheme worth $300,000, one third of which could be expended annually. This project would hire a lot of citizens in need. He expected work to proceed as soon as the frost was out of the ground. The Mayor also said that he had instructed the City Collector not to go after the unemployed for unpaid taxes until they had work.

The men next marched on the Parliament Buildings to seek an immediate interview with Premier Alexander Mackenzie, whose Liberal Party had come to power in November 1873, virtually at the onset of the depression—a timing that had not gone unnoticed by the unemployed workers. At the main entrance of the Centre Block, the men sent a messenger to the Premier who was in the Railway Committee Room attending a meeting of the House Banking and Commerce Committee. When Mackenzie refused to see them, the unemployed workers entered the building and approached the Committee Room’s entrance. They sent another messenger to Mackenzie. When nothing happened, two of the workers’ leaders opened the door, insisting to see the Premier. When a committee member shouted “Shut the door,” the door was closed in their faces. Indignant, some of the workers suggested starving them out “like they did at Sebastopol” during the Crimea War. Others forced the door to great cheers, including cheers for Sir John A. Macdonald, Mackenzie’s arch rival.

Needless to say, committee members were shaken by this invasion. Some apparently thought the men were there “to wipe them out.” However, others regained their composure and said that the men were harmless. They simply wanted to speak to Mr. Mackenzie. One of the unemployed men stood on a table and addressed the crowd. He was angry that the Premier had eluded them, calling it “a hardship and an insult.” Peter Mitchell, the MP for Northumberland County, New Brunswick, and a Father of Confederation, calmed them by saying that the Premier would no doubt give an interview at some other time and place. After giving three more cheers for Sir John A. Macdonald, the unemployed men left though not before issuing a statement:

“That we the unemployed workingmen of Ottawa, strongly censure the Hon. Alexander Mackenzie for refusing to meet a delegation sent from among us to ask his opinion as to the chances of work during the coming season. And we condemn him for allowing a door to be slammed in our faces, and call upon the workingmen of the Dominion to join us in rebuking the treatment received by us.”

The men made an orderly departure from Parliament, committing themselves to meet again in the Market later that day to plot strategy. That evening, the men, along with political representatives from all levels of government, met outside in the Market Square despite a light rain. Plans to meet in the Market Hall had been foiled by locked doors and a missing key. There was a number of rousing speeches. Mr. Bullman, the self-appointed chairman of the men, spoke on “how the wealth of the world was unequally distributed” and how the poor were oppressed. He said that he had been splitting hardwood for 25 cents a cord and had to feed a family of small children. (His credibility was later damaged when it was revealed that he was not unemployed, and had left a job at the gas works to attend the meeting.) A Mr. Hans added that “it was natural for money to flow into the rich man’s pocket as it was for the water of the St Lawrence to flow into the ocean.” At the end, it was agreed to send a deputation to approach Mackenzie on behalf of the workers.

At 9 am the next morning, a crowd of more than 600 gathered in front of the City Hall and marched to the West Block on Parliament Hill, the location of Premier Mackenzie’s office. The deputation, which comprised the City of Ottawa’s two MPs, one Liberal the other Liberal-Conservative, the Liberal MPP for the City, Mayor Waller, and Mr. Bullman, met with the Premier. This time, Mackenzie agreed to address the men.

The Premier offered the unemployed little in the way of government relief. He claimed that government was “powerless” beyond commissioning public works, pointing to the Welland and Lachine Canals. He also argued that aid should come from the provincial legislature and local charities. Just because Parliament resided in Ottawa was not a reason for the Dominion government to support Ottawa employment. If a man needed a job, he should go to the North-West Territories (Alberta and Saskatchewan) where he could get 100 acres of good farmland for nothing. However, Mackenzie promised that members of Parliament would personally donate as much as they could afford to relief efforts. He was also sure that the Ottawa men’s suffering was only temporary.

The Premier’s response did not go over well. There were more meetings, marches and speeches during the days that followed. The unemployed men sent a “memorial” (an archaic term for a public letter) to the Senate demanding government action in Ottawa and the surrounding area for public works to provide jobs and alleviate distress. Mayor Waller distributed “bread tickets” to the most urgent cases, while City Council expedited expenditures on the drainage project. A large number of men were put to work clearing out the Rideau Canal’s Basin. A relief fund was organized into which the Ottawa area’s more wealthy citizens contributed, including Alonzo Wright and Erskin Bronson. The Ladies Benevolent Society of St John’s Church held a fund raiser in the Temperance Hall selling “fancy work,” refreshments, and flowers and fruits. The take of the last show of the Grand Shaughraun Company at the Opera House also went to poor relief. These relief funds were managed by a committee of aldermen and clergymen which assessed each request for aid “to ascertain who is deserving and who is not.” These funds helped. But it was the arrival of warmer weather that had the most impact, with hundreds of men returning to jobs in the Chaudière lumber mills.

The following year, Sir John A. Macdonald’s Conservative Party thumped Premier Mackenzie’s Liberal Party in the 1878 federal election. This election ushered in the Conservative “National Policy” which sharply raised tariffs on American manufactured goods in order to boost the Canadian manufacturing sector, create jobs, and, just coincidently of course, to protect the interests of businessmen that supported the Conservative Party. Despite some tinkering around the edges, this high-tariff policy remained in effect until the Auto Pact of 1965.

This article was written by James Powell, the author of the Ottawa history blog "Today in Ottawa's History".

John Reeder: Webmaster and Walker Extraordinaire Retires

Our website is a vital tool in the Society’s communications tool kit. It not only informs members of upcoming events and Society news, it is our prime means of disseminating information about the Society and interesting Ottawa historical stories to the general public. Its reach is global; we have visitors from around the world. Look for a forthcoming HSO article on our readership.

Despite its success, few are probably aware of the person who built the website and maintained it since its inception. That person is John Reeder. In January 2007, he answered a small advertisement that appeared in the HSO quarterly newsletter that read “Help wanted. – HSO webmaster.” After being interviewed by then director Dave Mullington, John had the job. Just a couple of weeks later, on February 8, 2007, the Society’s website went live. It was a modest affair at the beginning, just a few webpages – a Home page as well as pages titled About Us, News, Executive Contacts, Coming Events, and Web Sites of Interest. But it launched the Society into the internet age.

Since that humble beginning, under John’s guidance, the HSO website grew in complexity and richness. It is now a fantastic repository of information not only about the Society and its many activities, but also about Ottawa’s history and heritage. For students of history, seventy-five issues of the Society’s Bytown pamphlet series are now available on the website free of charge, courtesy of John, as are a growing number of short historical stories on Ottawa. The website also provides a useful one-stop portal to numerous websites and blogs that touch on Ottawa history. As well, there are videos of old Ottawa that teleport us back into time.

But who is this volunteer benefactor of the Society, working steadily and virtually anonymously behind the scenes? John had a first career as a high school teacher. After he retired in 1998 after thirty-two years in front of a backboard, he started a second career. While he shuddered at the prospect of leaving teaching, retirement turned out to be the “best job” he ever had. John became a keen volunteer for a number of organizations, including Meals on Wheels and the Ottawa Heart Institute. Somehow, he also found the time to teach himself how to build and maintain websites. In addition to building the Historical Society's website, he worked on websites for the Ottawa Public Education Retirees Association, the Somerset Community Police Centre, the Ottawa Smockers’ Guild, and the Bethany Hope Centre.

John is also an inveterate walker, and has been since the first oil crisis of 1973. Looking for a way of reducing his energy consumption beyond the usual things like turning off lights and turning down the thermostat, he took up walking to and from work each day, rain or shine. This was not a trivial initiative, living as he did some four and half miles from his school. Think of doing that in a winter snow storm, or an autumn gale. As John wryly put, “Gene Kelly was a fraud,” referring to the Hollywood star dancing in the Hollywood classic Singing in the Rain. When he and his wife decided to give up suburban life to move downtown, his walk to school became seven miles each way! This necessitated him getting out the door by 4 am to be at work on time, with a midway stop at Tim Horton’s for a restorative bagel and coffee. Luckily for the Historical Society, he developed a keen appreciation for Ottawa, its neighbourhoods and its history on his walks to and from work.

Last year, John let us know that the Society should begin to think of replacing him. He noted that it was never a good idea for an organization to become dependent on one individual. And, while he was healthy, at age 76 he was no longer a “spring chicken.” Should he become unavailable for some reason, the Society could be severely disrupted. Prophetic words as it turned out.

Work began in the summer of 2019 on the daunting task of replacing John. As he used software that was not transferable to the Society, replacing him required the Society to move its website to a new platform. After investigating a number of alternatives, and realizing the extent of the job, the Society sought outside assistance. In late 2019, Vince and Cindy Murphy, who operate a small web design firm called ProbaseWeb from their home in Kemptville, Ontario, began the task of “migrating” our website to its new home. This will be the subject of a forthcoming HSO article.

In January 2020, John Reeder, the confirmed walker, slipped on the ice while passing through the courtyard at the city hall. It was a nasty break which required a number of pins and a plate. To add insult to injury, the break didn’t heal properly, requiring John to have to have a second operation in February. As a consequence, he and his wife were sadly unable to attend the Historical Society luncheon at the former All Saints’ Church in Sandy Hill. We had hoped to honour John and his incredible contribution to the Society over the years at the event.

Despite being one-handed and making frequent visits to the hospital and doctor, John continued to update our website, making his last changes in late February, just over thirteen years from when the site went live in 2007. Fortunately for the Society, work on the new website was almost complete. With the website management team, trained and in place, we were collectively able to assume John’s former responsibilities for maintaining and updating the new website in an almost seamless fashion.

Thank you, John, for all you did for us over the years. You will be missed. But your website legacy lives on. Good luck on your future endeavours.

The Canadian Historical Dinner Service

18 June 1898

When John Campbell Hamilton-Gordon, the 7th Earl of Aberdeen (later 1st Marquis of Aberdeen and Temair) was appointed Governor General of Canada in May 1893, few Canadians would have known that they were effectively getting two governors general rather than one. Lord Aberdeen’s wife, Ishbel, the Countess of Aberdeen, was not the traditional, self-effacing Victorian wife, content to live in the shadow of her illustrious spouse. While she fulfilled her expected roles of mother and hostess, her real passion in life was improving the lot of the poor, at home in Scotland, or wherever her husband was posted.

Both she and her husband were progressive socially and politically, with links to the Liberal Party. Back in Scotland, she had founded charitable organizations aimed at improving the education and health of working-class women. When her husband was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland during the mid-1880s (and again prior to World War I), it was hard to tell who worked harder. Sensitive to growing Irish nationalism, Lord Aberdeen favoured Home Rule while his Countess worked tirelessly for Irish economic development, and better health care and housing for Irish poor. A Sinn Féin (Irish Nationalist) newspaper called her “the real governor-general of Ireland.”

In Canada, Lady Aberdeen continued her social crusading ways. Immediately upon her arrival in the country, she launched the National Council of Women and was elected its first president, a position she accepted on the proviso she be considered an honorary Canadian. This was not some sinecure. She took the lead in making the Council a reality. She had already been elected President of the International Council of Women at the Chicago World Fair, a position she was to hold for more than thirty years. In 1897, she started the Victorian Order of Nurses in honour of Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, criss-crossing the country to drum up support and donations. She and other leading Ottawa ladies also worked hard to establish a public library in Ottawa, though this campaign didn’t bear fruit until some years after she and her husband had left Canada.

Charming, persuasive and an excellent orator, Lady Aberdeen’s effectiveness was also due to her willingness to use her high social position and contacts to her advantage. Needless to say, she irritated men who thought the role of the wife of a governor general should be limited to official hostess. Some saw her as bossy, sticking her aristocratic nose into things that weren’t her concern. One Halifax newspaper fumed that “we expect our Governors General to so govern their own families as to keep them out of mischief.” A New York newspaper said she was “too clever and too advanced for Canadians” and that she was “too much interested in movements.”

During Lord Aberdeen’s five-year appointment, the couple tirelessly crossed the country meeting and greeting Canadians of all types. They had a particularly strong connection with British Columbia where they had a large ranch. The Aberdeens are credited with launching the Okanagan fruit industry on a commercial scale. Lord Aberdeen, already extremely popular among Canadians of Scottish and Irish extraction, endeared himself to French Canadians by speaking French, and promoting French culture and heritage. It was he who started the practice of speaking in both official languages at public gatherings in Quebec. He also spoke Gaelic when he visited Nova Scotia. (There were so many Gaelic speakers that there was an attempt in the mid-1890s to make Gaelic Canada’s third official language.) Dinner plate, Parliament Buildings and Ottawa River by Martha Logan (1863-1937)

Dinner plate, Parliament Buildings and Ottawa River by Martha Logan (1863-1937)

Canadian Museum of History, Wikipedia.In 1898, Lord and Lady Aberdeen took leave of Canada. His last speech in the Senate was on 13 June 1898 when he prorogued Parliament. It was an emotional affair for all concerned. After the Governor General had concluded his valedictorian speech, people adjourned to the drawing room of the Senate’s speaker. There, Lady Aberdeen was given a farewell present, the gift of senators and members of parliament. The Honourable George William Allan of the Senate and Mr. Frank Frost, the Liberal MP of Leeds North and Grenville North made the formal presentation of a 204-piece formal dinner service. Speaking on behalf of everyone, Senator Allan said that the dinner service was a “memorial to their esteem and affection in recognition of the signal devotion of Her Excellency [Lady Aberdeen] to the promotion of all good works in Canada and [her] invariable kindness to the members of the Dominion Parliament.” He noted that the painted plates were the work of the Women’s Art Association of Canada and was hence “most suitable for presentation, both because it is purely Canadian and because it is the result of efforts of Canadian women, in whom Your Excellency has always shown the deepest interest.”

Fish plate, Cytherea gibbia, Halymenia ligulata by Lily Osman Adams (1865-1945)

Fish plate, Cytherea gibbia, Halymenia ligulata by Lily Osman Adams (1865-1945)

Canadian Museum of History, WikipediaLady Aberdeen was surprised and genuinely touched by the magnificent gesture. She responded without notes, saying that she was “overwhelmed” by the splendid gift. She added that the parliamentarians “could not possibly have chosen anything that [she and her husband] could have valued more,” and that it held “a special value to [her], being handiwork of those Canadian women workers with whom [she had] so many cherished associations of affectionate sympathy and co-operation for common aims and common works.” She concluded by saying that during every festive event, the plates would remind them of their stay in Canada.

The dinner service had its origins in an idea championed two years earlier by Mary Ella Dignam, the founder and president of the Women’s Art Association of Canada (WAAC) as a way of celebrating the 400th anniversary of the John Cabot’s journey of discovery to North America in 1497. Sixteen Canadian women artists were jury-selected to paint images of Canadian places of historic importance as well as examples of Canadian flora and fauna on the 204-piece, ceramic dinner service.[1] Dignam hoped that the Dominion Government would buy the service, which was called the Cabot Commemorative State Service, for use at Government House (Rideau Hall) for state banquets. The selling price was $1,000 (roughly $30,000 in today’s prices).

Soup plate, Entrance to Fort Lennox, by Clara Elizabeth Galbraith (1864-1941)

Soup plate, Entrance to Fort Lennox, by Clara Elizabeth Galbraith (1864-1941)

Canadian Museum of History, WikipediaIn an interview that appeared in The Globe newspaper in 1897, Dignam credited a Mr. Howland (most likely Oliver Aiken Howland, an Ontario politician and future mayor of Toronto) as coming up with the idea of commemorating the event with a historical work, and a Mr. Thompson with the suggestion that the work take the form of a state dinner service. However, Dignam was the person who brought the idea to fruition. In addition to honouring Cabot and equipping Rideau Hall with a distinctively Canadian dinner service for state events, Dignam hoped that the work would help establish ceramic art as a “permanent industry” in Canada.

The inspiration for a Canadian state dinner service appears to have come from south of the border. In 1879, the wife of then U.S. president Rutherford Hayes commissioned a state dinner service for the White House featuring American flora and fauna. The plates were designed by the American artist Theodore R. Davis and were produced by a company in Limoges, France. While this American service may have provided the model for the Canadian dinner service, Dignam was adamant that there was no resemblance between the two services except for their intended use. The American plates were designed by one man and decorated in one factory, whereas the Canadian plates were the designed by many female artists and were made across the country.

Dessert plate, Redcurrants by Alice M. Judd (18?-1843)

Dessert plate, Redcurrants by Alice M. Judd (18?-1843)

Canadian Museum of History, WikipediaAfter being selected through a competition, the sixteen artists bought commercially-produced, plain white, ceramic “blanks” produced by Doulton China of England for $6.60 a dozen. Dignam promised the artists at least $60 less ten percent for twelve pieces of original ceramic art, on the assumption that the service would be sold for $1,000. The rest of the funds raised would go to cover other expenses such as postage. If the service didn’t sell, the artists were on the hook to find buyers for their creations.

Each place setting consisted of a soup plate, fish plate, dinner plate, game plate, salad plate, cheese plate, dessert plate and a coffee cup and saucer. Each plate and cup had its own unique design. A ceramics committee of the WAAC provided a collection of pictures and sketches of Canadian historic sites, Canadian game animals, fish, shells and ferns for the inspiration of the artists. Artists were assigned plates to design, paint and fire. For example, Mrs Egan of Halifax and Miss Whitney of Montreal were assigned the game plates, with the former painting large game birds and the latter small game birds. On the rim of the game plates were painted the food favoured by the species shown in the centre. On the back of every plate was a special red logo of the shield of the WAAC surmounted by rendering of Cabot’s ship, the Matthew, with the dates 1497-1897 underneath.

The artists had only four months to complete their designs and fire the plates. Working in isolation from each other, the full dinner service was only seen in its entirety when the ceramics committee assembled it for inspection. The Cabot Commemorative State Dinner Service went on public display at the Pantecnetheca (116 Yonge Street) in Toronto in July 1897. It was subsequently displayed during the British Association meeting held in Toronto the following month, and at the headquarters of the WAAC where Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the Prime Minister, and Lady Laurier inspected the pieces. The dinner service then travelled to other cities for public viewing.

While the dinner service was highly praised, Mary Dignam was unable to persuade the Dominion Government to part with the $1,000 needed to cover the costs of production. So, Dignam approached Lady Edgar, the wife of the Speaker of the House of Commons, who put her in touch with a number of senators and members of Parliament. More than 150 senators and MPs put up the required $1,000 in a private subscription to purchase the dinner service to honour the Canadian achievements of Lady Aberdeen.

The dinner service, now called the Canadian Historical Dinner Service, went home with Lord and Lady Aberdeen and took up residence in their home, Haddo House, where it was stored in a specially-built cabinet. The dinner service, which is now owned by the National Trust of Scotland, resides there to this day. In 1997, part of the service was exhibited at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, now known as the Canadian Museum of History, for the 500th anniversary of John Cabot’s journey to North America.

Sources:

Duncan, March 2015, “An Irishman’s Diary on Lady Aberdeen,” The Irish Times, 3 March.

Elwood Marie, 2018. “The Cabot Commemorative State Service for Canada, 1897 – A History,” Canadian Museum of History.

—————–, 1977. “The State Dinner Service of Canada, 1898, Material Culture Review, Vol. 3, Spring.

Globe (The), 1897. “Chit Chat,” 15 April.

—————, 1897. “The State Dinner Set,” 23 July.

—————, 1897. “Chit Chat,” 8 October.

—————, 1897. “Ceramic Art,” 4 December.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1997, “Exhibits celebrate unusual art objects,” 8 September.

Ottawa Evening Citizen (The), 1898. “A Farewell to the Aberdeens,” 14 June.

[1] Lily Osman Adams, Jane Bertram, M. Louise Couen, Alice M. Egan, Clara Elizabeth Galbraith, Justina A. Harrison, Juliet Howson, Margaret Irvine, Alice Lucy Kelley, Margaret McClung, Hattie Proctor, M. Roberts, Phoebe Amelia Watson and Elizabeth Whitney.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Central Canada Exhibition

24 September 1888

For more than one hundred and twenty years, a feature of Ottawa life during the late summer or early fall was the Central Canada Exhibition. Now sadly defunct, the fair started as an agricultural and industrial exhibition, providing a venue for the farmers of eastern Ontario and western Quebec to display their products, share knowledge, and compete for prizes. It was also an opportunity for manufacturers to exhibit not only the latest agricultural equipment to potential buyers, but also other types of wares. Arts and crafts were additionally featured. It wasn’t all work, however. There was also entertainment, including circus acts, rides, games, and, of course, copious amounts of food and drink.

The Central Canada Exhibition began out of civic dissatisfaction with the annual Provincial Exhibition that was organized by the Agricultural and Arts Association of Ontario. The Provincial Exhibition, which was founded in 1845, moved from city to city in Ontario. However, local or civic fairs, including the Toronto Industrial Fair established in 1879 (to become the Canadian National Exhibition in 1912), began to compete with the more staid Provincial Exhibition. Although Ottawa hosted the Provincial Exhibition in 1887, it was not a great success. Many charged that the fair had been mismanaged, and that it had not been adequately promoted. As well, it appears that the Exhibition’s management irritated the wrong people. Ottawa’s Mayor Stewart was not amused when he was forced to pay a small fee for his horse when he arrived at Lansdowne Park, the venue that the city had provided rent-free to the Provincial Exhibition’s organizers.

Almost immediately after the Provincial Exhibition closed that year, a meeting was organized at Ottawa City’s Hall to discuss the merits of establishing Ottawa’s own annual agricultural fair. Chaired by Mayor Stewart, a long list of Ottawa’s great and worthy attended to voice their support, including Erskine Henry Bronson, a prominent Ottawa businessman and the member of the provincial assembly for Ottawa. (Bronson Avenue is named in his honour.) The Mayor also obtained the backing of the Premier, Sir John A. Macdonald.

Advertisement for the first annual Central Canada Exhibition

Advertisement for the first annual Central Canada Exhibition

The Evening Journal, 15 August 1888In March 1888, the Province of Ontario incorporated the Central Canada Exhibition Association for the promotion of “industries, arts and sciences generally,” and gave it “full power and authority to hold permanent or periodical exhibitions.” Ottawa’s mayor and three members of city council were appointed to the Association, along with representatives from eastern Ontario as far west as Kingston, and from western Quebec as far east as the Island of Montreal. In addition to agricultural groups, a long list of scientific and artistic groups were also to be represented, including the Ontario College of Pharmacy, the Ottawa School of Arts and Sciences, the Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society, the Geological Survey of Canada, and the Art Association of Ottawa.

In support of the new agricultural exhibition, the City provided $10,000 to upgrade the Exhibition Grounds at Lansdowne Park. These included the relocation of a number of buildings, the erection of a grandstand for two thousand people, and the construction of new floral and machinery halls. Opposite the grandstand, a temporary stage was also built for performances. The cattle sheds, horse boxes and the poultry sheds were freshly white-washed. The fairgrounds were also wired for electricity to permit the fun to continue after dusk; electric streetlights had come to Ottawa three years earlier. The City also made improvements to Elgin and Bank Streets that led to the Exhibition Grounds. The admission fee to the Exhibition was 25 cents. A single carriage with a driver got in for 50 cents, with 25 cents charged for each additional passenger.

All was ready when Exhibition’s doors opened on 24 September 1888; the official inaugural ceremonies took place the following day in the presence of the Governor General, Lord Stanley of Preston. Ottawa was dressed to the nines for the event, with its store windows decorated and flags and bunting everywhere. There were close to 5,000 entries to the Exhibition, twice the number of the previous year’s Provincial Exhibition. Over three hundred horses were on show, including standard horses, blood horses, carriage horses, roadsters, and saddle horses, hunters and heavy draught horses. In the cattle shed could be found Durhams, Ayrshires, Galloways, Herefords, Holsteins, and Polled Angus. In the poultry shed, there were 110 entries in twenty varieties of chicken, including Plymouth Rooks, Cochin Chinas, White and Black Polands, and White Leghorns, as well as turkeys, geese, and pigeons.

The main building housed miscellaneous manufactures, ranging from hardware and harrows, to home furnishings, including the latest in labour-saving devices such as mangles, washing machines, and sewing machines. There were displays of “fancy work,” embroidery, paintings in watercolours and oils, and an “endless display of tidy and kindergarten work.” Two hundred entries were devoted to textile goods alone made from Canadian wool. In the carriage department, one hundred vehicles were on display—coaches, landaus, coupes, phaetons, tea carts, sulkies, 2-horse teams, market wagons, and sleighs. In an annex to the main building, R.J. Devlin, a large Ottawa department store, put on a massive display of furs with everything from musk ox to Persian lamb. Visitors were wowed by two stuffed polar bears and a Bengal tiger skin that stretched twenty feet from nose to tip of its tail.

The newly constructed machinery hall housed steam and horse-powered threshers and separators, ploughs, reaping and mowing machines, combines, windmills and stump extractors—everything a farmer could wish for. A “waterous engine” driving “hundreds of busy wheels,” transfixed visitors. A massive collection of minerals was also on display. All categories of machines, animals, plants, and crafts were judged with monetary prizes ranging from $25 to $5 in addition to gold, silver and bronze medals for first, second and third places, respectively. Diplomas were also awarded.

Advertisement for the parachute jump, 1st Annual Central Canada Exhibition

Advertisement for the parachute jump, 1st Annual Central Canada Exhibition

The Evening Journal, 19 September 1888.After the opening ceremonies, described as a “very recherché affair,” by the Ottawa Evening Journal,” there was a luncheon for the dignitaries, hosted by President Charles Magee of the Exhibition Association. The guests of honour were Lord Stanley and Acting Mayor Joseph Erratt; Mayor Stewart was in England and missed the Exhibition. He did, however, supply a number of cases of champagne to toast his health. Unsurprisingly, the mayor’s tent was very popular that afternoon, something that couldn’t have gone over well with the Women’s Christian Temperance Union who had been grudgingly allowed to have a booth at the Exhibition. Music for the day was provided by the band of the Governor General’s Foot Guards.

That evening, with the electric lights illuminating the Exhibition grounds, the games began over the objections of clergymen who objected “most strongly” about turning an agricultural fair, aimed at improving and instructing people, into anything that resembled fun. Roman chariot races were held on the race track with teams of eight horses. This was followed by a series of circus acts. The Zanfretta family of New York performed a high-wire act with Mr Zanfretta carrying Miss Zanfretta across a rope suspended fifty feet in the air. Levanian and McCormick performed on the trapeze, while Professor Chiton juggled, and the Rice Brothers performed acrobatics. Other performers included Val Vina, a comic juggler, and Philion, the French Necromancer. Mr Topley, Ottawa’s premier photographer, also provided stereopticon views of old and new Ottawa. To cap the evening’s festivities was a brilliant fireworks display.

The next day, the highlight of the Exhibition, was the ascension of a hot-air balloon to 6,000 feet, from which a Professor Williams would make a parachute jump. The event was described as “the greatest out-door wonder the world has ever witnessed.” Ballooning and parachuting in the 1880s was not for the faint at heart. Balloonists were frequently injured or killed. One contemporary observer commented that “we are no more masters of the balloon than they [the Montgolfier brothers] were a century ago.” To jump from a balloon was an order of magnitude even more dangerous given the primitive parachutes of the time.