James Powell

The Rise and Fall of the Daly Building

14 June 1905

One of the greatest heritage battles in Ottawa’s history was fought over the future of the Daly Building, a multi-storey, former department store cum government office building located in the block bounded by Mackenzie Avenue, Rideau Street and Sussex Avenue. The architectural and historic merits of the building, constructed in what is known as the “Chicago style,” were debated ad nauseam for years if not decades in Ottawa’s newspapers, at City Hall, and at the National Capital Commission. While all could agree that something had to be done with the aging building, what that something was sharply divided Ottawa residents. As it turned out, the building, which was vacated by its last tenants in 1978, was left empty for thirteen years as the federal government, the owner of the property, dithered. It was hastily demolished in 1991, amidst a huge outcry, after a renovation attempt fell through. Paralleling what happened with LeBreton Flatts, the land was then left fallow for more than a decade. After many different development concepts were advanced and discarded, the government finally leased the property to Claridge Homes for an up-scale condominium building that opened in 2005.

The edifice which was to become known as the Daly Building, was built in 1904-05 by the Clemow Estate, under the supervision of Mr. William F. Powell who managed the Estate’s business affairs. Powell had originally hoped to build a hotel on the site. (This was before the Château Laurier was constructed across the street.) But when his hotel plans fell through, Powell negotiated a deal with Thomas Lindsay, a prominent Ottawa merchant who owned T. Lindsay Company, a department store on Wellington Street, and Larose & Company on Rideau Street. Under the agreement, the Clemow Estate would build a modern, five-storey, department store building that Thomas Lindsay would lease.

In preparation for the project, Powell travelled to New York on a fact-finding mission about the large department stores of that city. He then engaged Moses C. Edey as architect. Edey was no stranger to Ottawa. Born in Wyman, Quebec, the Edey family had come to the Hull area in 1805 with Philemon Wright. Edey was the architect of the Aberdeen Pavilion at Lansdowne Park completed in 1898. For the new department store, Edey chose what was for the time a daring new form of architecture that relied on a steel and stone external framework that permitted the installation of large, plate-glass windows. There was so much external glass that the Evening Journal commented that the building should be called a “crystal palace.” There were no interior walls, allowing maximum flexibility to organize the space. Instead, the floors were supported by 32 steel columns clad in Portland cement. This “Chicago School” form of construction is considered to be the forerunner of the modern glass and steel office tower.

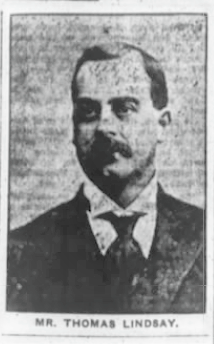

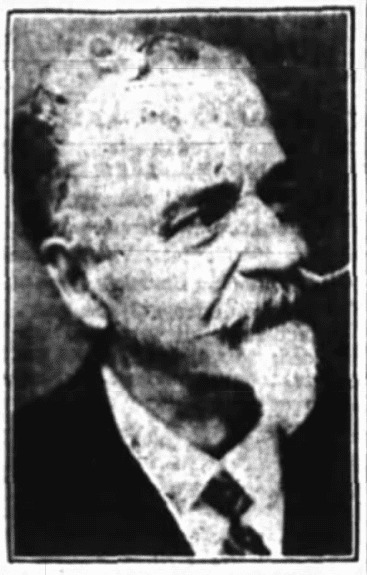

Thomas Lindsay, builder of what later would be known as the Daly Building, Ottawa Evening Journal, 15 June 1905.Ground was broken for the five-storey building (four storeys on the Mackenzie Avenue since the edifice was constructed on a slope) in the summer of 1904, and was completed a year later. The new Thomas Lindsay Company department store opened its doors for business on 14 June 1905.

Thomas Lindsay, builder of what later would be known as the Daly Building, Ottawa Evening Journal, 15 June 1905.Ground was broken for the five-storey building (four storeys on the Mackenzie Avenue since the edifice was constructed on a slope) in the summer of 1904, and was completed a year later. The new Thomas Lindsay Company department store opened its doors for business on 14 June 1905.

Thomas Lindsay, who had started the eponymous firm roughly fourteen years earlier at his Wellington Street location, was known for selling goods at low prices. His company was advertised as “The House of Bargains” and “the store where money has the greatest purchasing power.” But there was no stinting on the interior furnishings and fittings of his new department store. As well as having wide staircases, the store was serviced by three elevators, two for customers and one for freight. In addition to the natural lighting provided by the large plate glass windows, which were fitted with pivoting devices that permitted them to swivel open for easy cleaning and fresh air, the building was equipped with electric lighting. Around every other pillar on each floor was a large display table for goods. Every floor was serviced by a pneumatic tube, cash-carrying system, and had ladies’ and gentlemen’s toilets, all furnished with hot and cold running water. On the second floor overlooking Major Hill’s Park there was a large drawing room for visitors where they could go to sit, relax, read the latest magazines, or write letters. A ladies’ “retiring room” was off of this.

On opening day, only three floors were finished; the upper two floors were completed by the fall. On the ground floor, off of Sussex Street, there was the men’s and boy’s clothing departments, a grocery equipped with a three-compartment refrigerator, and a drug store. On the first floor (accessed through the Mackenzie Street entrance), were the ladies’ department, and a “small wares” department. There were offices the third floor. Home furnishings, carpets, and hardware were located on the upper two floors once they were completed.

In 1906, Thomas Lindsay Company bought the building, as well as an adjacent empty lot to the north of the original structure, and other nearby properties from the Clemow Estate for reportedly $350,000. Lindsay’s intention was to increase the floor space of the department store by adding two floors, as originally designed by the building’s architect, and by extending the building onto the empty lot. However, these plans were delayed, possibly due to Thomas Lindsay’s declining health. In 1909, Thomas Lindsay sold his controlling interest in the Thomas Lindsay Company to the Rea brothers of Toronto for $300,000; the business had become too much for him. He died shortly after the sale.

The Rea brothers had retail experience in Toronto, having sold a similar store there to Robert Simpson, the owner of Simpson’s Department Store. After a short delay, they changed the name of their new department store to the A.E. Rea Company. In 1913, they undertook the store’s expansion as originally envisage by Lindsay. Other changes included a shortened work week. No longer would employees start work at 7:30am. Instead there would be a nine-hour day beginning at 8.30am, running until 5:30pm. As well, a new money-back guarantee was introduced. Also changed was the advertising policy of the store. Thomas Lindsay had withdrawn all advertising from the Ottawa Citizen in early 1908 owing to the newspaper’s opposition to the City taking over the Metropolitan Company’s water power operations at Britannia. Lindsay, who was a major shareholder in the power company, favoured the sale. Lindsay’s ban on advertising in the Citizen was revoked when the Rea brothers purchased the store.

Construction of the Daly Building extension northward along Sussex Street. The Château Laurier Hotel is in the background, 1913, Library and Archives Canada, Topley Studios, ID #3410293.

Construction of the Daly Building extension northward along Sussex Street. The Château Laurier Hotel is in the background, 1913, Library and Archives Canada, Topley Studios, ID #3410293.

In late 1917, the Rea brothers, who had overextended themselves, ran into financial difficulty. Liquidators were called in to settle their affairs with the stock and assets of the department store sold off at 40 cents on the dollar. The big department store passed into the hands of H. J. Daly who took over the business and ownership of the building in February 1918.

Advertisement that appeared in the Ottawa Journal 28 February, 1918.Oddly, for a building that bore his name for the rest of the century, Daly didn’t own it for very long—less than four years. In 1919, Daly moved his department store operations to a new store built on Sparks Street on a site previously occupied by the Arcade building (roughly where the CBC building is today) which had burnt down in a huge conflagration in December 1917. By mid-August 1919, the Daly Building was vacated and rented to the Federal Government which subsequently bought it for $1 million in late 1921. The H. J. Daly department store did not last long in its new Sparks Street location. It failed in early 1923.

Advertisement that appeared in the Ottawa Journal 28 February, 1918.Oddly, for a building that bore his name for the rest of the century, Daly didn’t own it for very long—less than four years. In 1919, Daly moved his department store operations to a new store built on Sparks Street on a site previously occupied by the Arcade building (roughly where the CBC building is today) which had burnt down in a huge conflagration in December 1917. By mid-August 1919, the Daly Building was vacated and rented to the Federal Government which subsequently bought it for $1 million in late 1921. The H. J. Daly department store did not last long in its new Sparks Street location. It failed in early 1923.

As for the Daly Building itself, it was the home of a variety of federal government departments over the next fifty plus years, starting with the Department of Health in 1919 and ending as the Customs and Excise training centre in 1978. Its last private-sector tenant was Ad Lib, a women’s clothing store.

Discussion about pulling down the building began in 1954 when Jacques Gréber, the noted French urban planner who advised the federal government on how to beautify the Capital, recommended replacing the Daly building with a three-floor parking garage with a park on top. His suggestion did not go over well with Mayor Charlotte Whitton. The Minister of Public Works announced that other departments needed the space and the idea quickly faded.

But by the late 1970s, the building was in poor condition. As well, past renovations, which included replacing the windows during the 1920s and the removal of the decorative cornice in 1964 over concerns that pieces might fall and hurt passing pedestrians, were not sympathetic to the original design. With lots of new federal office space just built in Hull, the Daly Building was surplus to requirements. The Department of Public Works announced that since it was not economic to renovate it, the building would be demolished in 1979.

This set off a huge fight between conservationists and demolishers within the federal government, architect associations, and the heritage community over the merits of the conserving the only example of “Chicago-style architecture” in the city. As the war of words raged, the building slowly deteriorated. On the side of saving the former department store were Ottawa mayor Marion Dewar, and Jean Pigott, for a time the Chair of the National Capital Commission in the mid-1980s. Heritage Ottawa and a dedicated lobby group called Friends of the Daly Building also called for its restoration. Others, however, applauded its demolition. Charles Lynch, the noted Canadian journalist, author, and one-time former governor of Heritage Ottawa called the Daly Building “an ugly duckling: a former failed department store, failed office building, and successful eyesore.” He opined that the structure offered nothing of note or of beauty, either outside or inside, and he would be “honoured to strike the first blow when the wreckers come.” Another commentator wrote that the “heritage movement risked “making a fool of itself by unwise support of an unworthy cause.” He argued that to spend millions to “create a museum for architects when the general population hated the building was a form of “elitism.”

The hammer finally came down in September 1991 when the National Capital Commission announced that it didn’t believe that a group of developers (Coopdev and its partner Duroc Enterprises) would be able to finish a planned $45 million renovation by September the following year owing to the developers’ inability to find a major tenant for the renovated structure. When Coopdev failed to pay its first $60,000 payment in monthly rent on its 66-year lease, the NCC fired the company. The Daly Building was hastily demolished just a few days later.

700 Sussex Street, site of the “Daly Building,” Google Maps, May 2019.Over the following fourteen years, suggestions came and went on what to do with the property. Should it be a park, a parking garage, or some new prestige project? One idea that gained some traction for a while was to build a performing arts centre to celebrate Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Noted Canadian architect, Douglas Cardinal, reportedly agreed to design the centre. The idea flopped. In the late 1990s, Gateway Development Corp. proposed building an upscale hotel on the site, with retail stores on the ground level, loft apartments, and, believe it or not, an underground aquarium. The proposal failed to receive the necessary financial backing and the project collapsed.

700 Sussex Street, site of the “Daly Building,” Google Maps, May 2019.Over the following fourteen years, suggestions came and went on what to do with the property. Should it be a park, a parking garage, or some new prestige project? One idea that gained some traction for a while was to build a performing arts centre to celebrate Canada’s Indigenous peoples. Noted Canadian architect, Douglas Cardinal, reportedly agreed to design the centre. The idea flopped. In the late 1990s, Gateway Development Corp. proposed building an upscale hotel on the site, with retail stores on the ground level, loft apartments, and, believe it or not, an underground aquarium. The proposal failed to receive the necessary financial backing and the project collapsed.

The NCC finally reached a deal with Claridge Homes and its president Bill Malhotra, under which the developer would lease the site for 66 years and build an eleven-storey condominium building with an open-air roof deck and garden on the eighth floor. The 70 luxury apartments ranged in size from roughly 1,000 to 2,300 square feet in size. The price for the one of the penthouse suites reportedly topped $1.75 million… and this was in 2002! Despite the eye-watering prices, 700 Sussex Drive proved to be a great success and quickly sold out.

While the old Daly department store is now long gone, its spirit is still with us. Dan Hanganu, the architect for the new condominium development, apparently drew his design inspiration from the old department store.

Sources:

Heritage Ottawa, Daly Building, https://heritageottawa.org/50years/daly-building.

Ottawa Citizen, 1905. “Clemow Estate,” 12 June.

——————, 1905. “Opening Of Ottawa’s New Palatial Store,” 10 June.

——————, 1905. “Congratulations,” 15 June.

——————, 1909. “Control May Change Hands,” 3 August.

——————, 1909. “The Lindsay Sale,” 7 August 1909.

——————, 1909. “Style Center Of Canada,” 18 August.

——————, 1909. “A Bit Of Local History,” 20 August.

——————, 1909. “Shorter Hours For Employes (sic),” 25 August.

——————, 1954. “Mayor Calls Greber Parking Plan Speculative Newspaper Story,’” 14 September.

——————, 1985. “An Argument for preservation of the Chicago Style Daly Building,” 16 November.

——————, 1991. “A Thing of the past,” 5 September.

——————, 1991. “Why doom the Daly building now?,” 7 September.

——————, 1991. “Start the Demolition!,” 8 September 1991.

——————, 1991. “Heritage falls off the Day tightrope,” 20 October.

——————, 1999. “Remembering the Daly Building,” 15 August.

——————, 2002, “Long lineup for Luxury Daly Units,” 9 January.

Ottawa Evening Journal, 1904. “Palace Store on Clemow Site,” 13 June.

—————————–, 1905 “Many Expressions of Good Will From Many Friends,” 15 June.

—————————–, 1918. “The Rea Store, Announcement Extraordinary,” 5 January.

—————————–, 1921. “Property Transfers For Large Amounts,” 2 November.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Television Arrives in Ottawa

2 June 1953

By the late 1930s, commercial television broadcasting was ready for “prime time” after years of experimentation, first with mechanical systems and later with electronic systems. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is credited with the first “high-definition” television broadcast when it began regularly scheduled transmissions in late 1936 from its studios at the Alexandra Palace in London using Marconi-EMI’s fully electronic system. “High definition” in this context should not to be confused with today’s high-definition television. The BBC was broadcasting with just 405 lines of resolution, much less than the 720-1,080 lines considered to be high definition today. Its broadcast resolution was, however, far superior to that of earlier broadcasting systems that had resolutions ranging from roughly 30 to 204 lines. The BBC station’s range was officially only forty kilometres, though unofficially it could reach much farther depending on atmospheric conditions. BBC television quickly became a big hit; the hot, new gift in London during the 1937 Christmas season was the television set. Some 10,000 receivers were sold. But progress came to a halt at the outbreak of World War II when the BBC suspended its broadcasts owing to fears that German bombers could use its signal to home in onto London. BBC technicians were also needed elsewhere to support the war effort.

In North America, experimentation also went into high gear during the 1930s. The Canadian experimental station VE9EC, owned by La Presse and CKAC radio in Montreal, broadcasted during the early years of the decade using mechanical systems with 60-150 lines of resolution. In the United States, a number of competing broadcasting systems were also being tested and perfected. The Radio Corporation of America (RCA) began regular experimental television broadcasts in New York City in the spring of 1939, transmitting monochrome (i.e., black and white) programmes from the top of the Empire State Building. RCA’s television subsidiary became the National Broadcasting Corporation (NBC). That same year, RCA began to ramp up its production of television receivers for sale to the general public. RCA also demonstrated the television at the 1939 Canadian National Exposition in Toronto, marketing it as “science’s most modern miracle,” that will soon feature in every home. In 1940, the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) began regular black-and-white television broadcasting in the United States. In the spring of the following year, U.S. regulators adopted the 525-line resolution as the standard for the American television industry, allowing commercial television to move out of its experimental phase. However, like in Britain, the United States’ entry into the war delayed a wider roll-out of commercial television as vacuum tubes used in television sets were required for defence purposes.

With the war’s end in 1945, television took off in the United States. While initially confined to the major urban centres, the number of stations rose from 16 in 1948 to 354 by 1954. In 1947, 179,000 television sets were produced in the United States. By 1953, annual production was more than 7.2 million. This compares with only 2,000 receivers in use at the end of 1939.

Notwithstanding its success south of the border, television was slow to come to Canada. In 1947, senior Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) officials declared that “the time had not yet come for the general development of television on a sound basis in Canada.” Not surprisingly, given the burgeoning growth of U.S. television, there was criticism that CBC was dragging its feet. There were also fears that Canada was falling behind the United States and other competitors in the technology race. Two related and highly political issues were delaying television’s Canadian debut—ownership and funding. The big question was whether Canada should have a national, state-owned television network, similar to publicly-owned networks in Europe, which would promote Canadian values and culture, or allow private television networks, as in the United States, that might be foreign owned, and broadcast foreign shows. There was also considerable controversy about the cost of building a Canada-wide television network. The initial funding for CBC television was placed at $4.5 million (roughly $46 million today). Later, material shortages were also cited as delaying the building of stations, with expansion beyond Toronto and Montreal dependent on the defence production programme associated with the Korean War.

In part, the government’s hand was forced by US border stations whose signals could be picked up by Canadians living close to the U.S. border. In Ottawa, the signal from the NBC affiliate WSYR-TV from Syracuse, New York could be picked up from early September 1951. The Evening Citizen reported that a Mr Kitchen of 350 Chapel Street managed to receive a good video signal with his home-made antenna and three home-made boosters. Canadian television was finally born on 6 September 1952 when CBC’s Montreal station CBFT began regular programme broadcasts. Its Toronto station, CBLT, commenced broadcasting two days later.

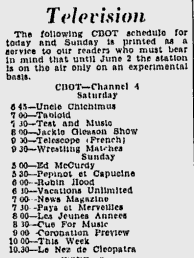

First programme listing for CBOT, The Ottawa Evening Citizen, 30 May 1953.Canadian television officially arrived in Ottawa at 2pm on 2 June 1953 when CBOT, the CBC’s third station, began regular broadcasting. Using equipment supplied by Marconi’s Wireless and Telegraph Company of Montreal, the station initially had a range of only 15 miles (24 kilometres). Its signal was later boosted to have a range of 40 miles (65 kilometres). Found on channel 4 on the television dial, CBOT actually started testing its equipment roughly two weeks earlier when a microwave relay tower built on the top of the Bell Telephone Building on O’Connor Street became operational. The microwave system, which could simultaneously carry both telephone and television signals, linked Ottawa to Toronto and Montreal. After test programmes were transmitted with “astonishing clarity” over the long May weekend, the station felt confident enough to list its programming schedule for Saturday, 30 May in the newspaper, albeit with a warning that it was still operating on an experimental basis. The station, which broadcasted for less than four hours that day, started at 6.45pm with Uncle Chichimus, the much beloved Toronto-based production starring John Conway and his two puppets, Uncle Chichimus and Hollyhock. The evening’s entertainment ended with an hour of wrestling starting at 9.30pm. During these early days of television, CBOT, like the Montreal station CBFT, offered programs in both English and French, a practice that continued until Radio Canada had its own stations. That first night’s French-language program was called Télescope.

First programme listing for CBOT, The Ottawa Evening Citizen, 30 May 1953.Canadian television officially arrived in Ottawa at 2pm on 2 June 1953 when CBOT, the CBC’s third station, began regular broadcasting. Using equipment supplied by Marconi’s Wireless and Telegraph Company of Montreal, the station initially had a range of only 15 miles (24 kilometres). Its signal was later boosted to have a range of 40 miles (65 kilometres). Found on channel 4 on the television dial, CBOT actually started testing its equipment roughly two weeks earlier when a microwave relay tower built on the top of the Bell Telephone Building on O’Connor Street became operational. The microwave system, which could simultaneously carry both telephone and television signals, linked Ottawa to Toronto and Montreal. After test programmes were transmitted with “astonishing clarity” over the long May weekend, the station felt confident enough to list its programming schedule for Saturday, 30 May in the newspaper, albeit with a warning that it was still operating on an experimental basis. The station, which broadcasted for less than four hours that day, started at 6.45pm with Uncle Chichimus, the much beloved Toronto-based production starring John Conway and his two puppets, Uncle Chichimus and Hollyhock. The evening’s entertainment ended with an hour of wrestling starting at 9.30pm. During these early days of television, CBOT, like the Montreal station CBFT, offered programs in both English and French, a practice that continued until Radio Canada had its own stations. That first night’s French-language program was called Télescope.

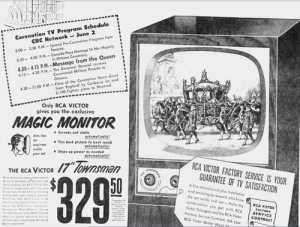

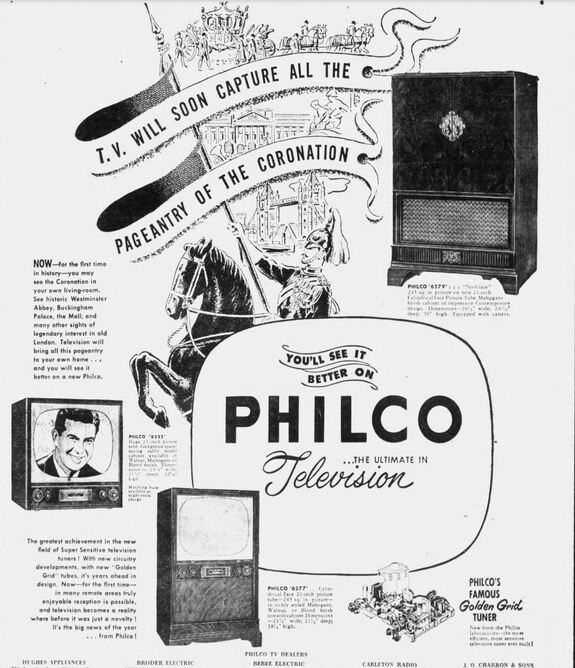

Ottawa Evening Citizen 28 May 1953.The official launch of CBOT on 2 June 1953 was timed to coincide with an event guaranteed to attract the largest audience possible—the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Not only were celebratory events on Parliament Hill in Ottawa televised on the three CBC stations, but the entire Coronation ceremony from London with a delay of only four hours. In “Operation Pony Express,” three RAF Canberra bombers flew film footage across the Atlantic from North Weald Airport outside of London to Goose Bay, Newfoundland, with the first plane carrying the first two hours of film coverage, with the other two planes following with later hours of coverage. In Goose Bay, the film canisters were transferred onto RCAF CF-100 fighters for the flight to the St Hubert Airport outside of Montreal. A truck then took the film to the Radio Canada building in downtown Montreal for broadcasting, with simultaneous viewing in Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa. Coverage of the Coronation from London started at 4.30pm, after a broadcast of the ceremonies on Parliament Hill, and the Queen’s Coronation message. Prior to the start of its Coronation coverage, CBC broadcasted a test pattern and music. Regular updates on the status of the Canberra flights were also provided. The Coronation broadcast was in black and white; colour programming would not be launched in Canada until 1966, thirteen years after colour was introduced in the United States. If people wanted to see the Coronation in colour, they had to go to the cinema when the film became available a few days later.

Ottawa Evening Citizen 28 May 1953.The official launch of CBOT on 2 June 1953 was timed to coincide with an event guaranteed to attract the largest audience possible—the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Not only were celebratory events on Parliament Hill in Ottawa televised on the three CBC stations, but the entire Coronation ceremony from London with a delay of only four hours. In “Operation Pony Express,” three RAF Canberra bombers flew film footage across the Atlantic from North Weald Airport outside of London to Goose Bay, Newfoundland, with the first plane carrying the first two hours of film coverage, with the other two planes following with later hours of coverage. In Goose Bay, the film canisters were transferred onto RCAF CF-100 fighters for the flight to the St Hubert Airport outside of Montreal. A truck then took the film to the Radio Canada building in downtown Montreal for broadcasting, with simultaneous viewing in Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa. Coverage of the Coronation from London started at 4.30pm, after a broadcast of the ceremonies on Parliament Hill, and the Queen’s Coronation message. Prior to the start of its Coronation coverage, CBC broadcasted a test pattern and music. Regular updates on the status of the Canberra flights were also provided. The Coronation broadcast was in black and white; colour programming would not be launched in Canada until 1966, thirteen years after colour was introduced in the United States. If people wanted to see the Coronation in colour, they had to go to the cinema when the film became available a few days later.

With the day declared a national holiday, people scrambled to find a television to watch the historic event. In Ottawa, the Radio and Television Manufacturers Association of Canada installed televisions in every school without charge to allow all students to watch the Coronation. An abridged French-language version was also televised. Naturally, parents were invited to watch as well–a good marketing ploy. Stores also offered special Coronation deals so that families could watch the events on their own sets. One enterprising store invited those uncertain about television, or were unable to afford a receiver (the price for the monochrome receiver started at $249.99, equivalent to $2,200 today), to come in and watch the Coronation on its sets for free.

From that day on, there was no looking back. Television quickly became, as RCA had predicted in 1939, an indispensable part of every Canadian household. In 1948, there were only 325 TV sets in Canada. In 1951, roughly one percent of Canadian households, mostly located in southern Ontario in range of American TV signals, had purchased a TV set. Ten years later, 83 per cent of Canadian households had a television, a higher percentage than that of homes with indoor plumbing.

Sources:

Canadian Communications Foundation, 2013. Television Station History, Ontario, Eastern Canada, CBOT-DT (CBC Nework), Ottawa, http://www.broadcasting-history.ca.

CBC-Radio Canada, 2015. Our History, http://www.cbc.radio-canada.ca/en/explore/our-history/.

CBC, 2015, “A TV Renaissance, TV In Canada, A History,” Doc Zone with Ann-Marie MacDonald, http://www.cbc.ca/doczone/features/tv-in-canada-a-history.

Freemeth, Howard, 2010, “Television,” Historica Canada, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/television/.

Hammond Museum of Radio, 2004, “Some Dates From Canadian Broadcasting,” http://www.hammondmuseumofradio.org/dates.html.

TV History, 2013. Television History—The First 75 Years, Television Facts and Statistics—1939 to 2000, http://www.tvhistory.tv/facts-stats.htm.

The Evening Citizen, 1951. “Ottawans Get Good Video Reception,” 11 September.

————————, 1953. “Fly TV ‘Take’ To CBC: See Coronation Same Day Here,” 6 May.

————————, 1953. “Ottawa Microwave Radio Relay Tower In Operation on May 14th,” 6 May.

————————, 1953. “TV Sets To Be Installed In Schools For June 2,” 26 May.

————————, 1953. “Station CBOT Now On The Air Each Night,” 26 May.

————————, 1953. “Television,” 30 May 1953. The Globe and Mail, 1937. “Television Is London’s Newest Christmas Gift Idea,” 13 December.

————————, 1938. “10,000 Sets Made And Sold In United Kingdom,” 13 January.

————————, 1941. “Commercial Television Is Delayed By Defense,” 3 July.

————————, 1947. Television—Canada Not Ready, Says Frigon,” 28 June.

————————, 1949. “Ottawa Studies Loan in Millions for CBC Video,” 2 March.

————————, 1949. “Claims TV Delay Due To Ottawa Pre-Election Fears,” 3 May.

————————, 1951, “Hints Windsor, Ottawa, Quebec Next In Line For Canadian Television,” 16 November.

———————-, 1953. “Temporary Television Hookup To Let Ottawa See Coronation,” 13 March.

———————-, 1953. “Jets Bring Coronation Films For TV Viewers on Tuesday,” 30 May.

———————-, 2014. “Ferris-Wheel highs and nauseating lows from 135 years of the Ex,” 13 August.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

HSO Community Project Chosen

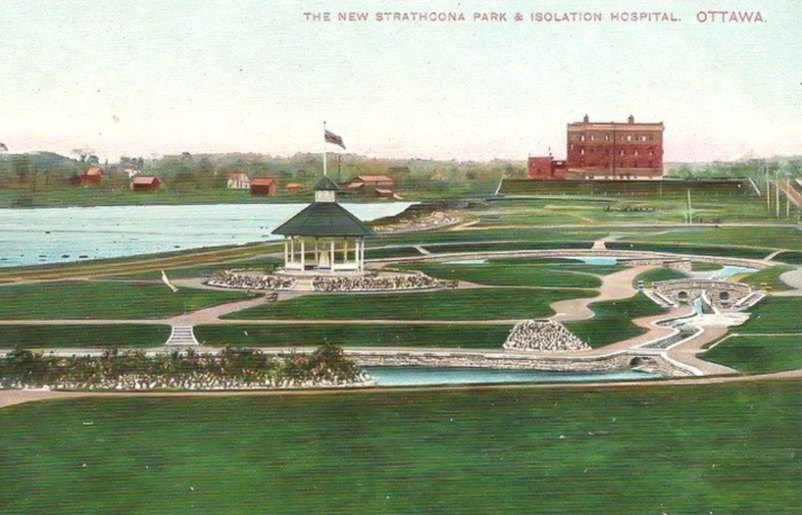

The Society’s Board of Directors is delighted to announce that it has approved a pledge of $5,000 towards a project to construct a replica gazebo at Strathcona Park. This project was proposed by HSO member, François Bregha.

At last year’s Annual General Meeting, members agreed to allocate funds to finance community projects over the coming years. Members were asked to suggest potential projects, and a process was established to choose among projects. The selection process was based on a number of criteria, including relevance to HSO’s mission and objectives, cost, and the availability of people to take the lead on the project.

The construction of a replica pavilion at Strathcona Park has long been the dream of Action Sandy Hill, a local community group. Strathcona Park, which is located on the western bank of the Rideau River, was originally the home of the Dominion Rifle Range. During the early 20th century, the range was turned into a park by the Ottawa Improvement Commission, the forerunner of the National Capital Commission. The park is now maintained by the City of Ottawa.

The park was named in honour of Scottish-Canadian businessman, financier and politician Donald Smith who became 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal in 1900. During the nineteenth century, Smith was president of the Bank of Montreal, and co-founded the Canadian Pacific Railway with his cousin George Stephen, later known as Lord Mount Stephen. Smith also for a time represented Montreal in the House of Commons. Later, he became Canada’s High Commissioner to London. Lord Strathcona was also a great philanthropist, endowing hospitals, including the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. He was also Chancellor of McGill University and the University of Aberdeen.

A feature of Strathcona Park is a large fountain sculpture by Mathurin Moreau which was donated by Lord Strathcona in 1909. The four standing figures supporting a bowl represent Europe, Asia, Africa and America. Another original feature of the park was a Victorian-style gazebo, the site of many band performances and other events. Unfortunately, the aging gazebo was dismantled in 1961 and never replaced. The initiative of Action Sandy Hill to re-build the gazebo will restore a historic structure and provide a new focal point for the Park.

Planning for the structure is well advanced. Action Sandy Hill (ASH) will allocate up to $26,000 to this endeavour using money received from a developer earmarked for community benefits. The City of Ottawa has agreed to match the ASH funds. Heritage architect Barry Padolsky is contributing the gazebo design and specifications pro bono. Action Sandy Hill held a community consultation on the gazebo in September 2020 and is looking for estimates for its construction. It is also seeking funds from the broader Ottawa community to complete the financing.

The Historical Society of Ottawa is delighted to support this initiative to rebuild the gazebo and reintroduce a lost historical artifact in a well-used and much-loved park.

The tall building in the background is the isolation hospital, now the site of an apartment building.

The Phantom Air Raid

14 February 1915

One of the most curious events in Ottawa’s history occurred on Valentine’s Day night, Sunday 14 February 1915, six months after the start of the Great War. At roughly 10.30pm, the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, received an urgent telephone call from Mayor Donaldson of Brockville informing him that at least three German airplanes had crossed the St Lawrence River from Morristown, New York. The invaders, apparently seen by scores of Brockville citizens who were returning from Sunday evening church services, had just passed directly over the community travelling in a northerly direction, presumably towards the capital. One of the planes shone a powerful searchlight on the town, lighting up its main street. Reportedly, the planes dropped “fireballs,” or “light balls,” into the river on the Canadian side of the border. Many Brockville citizens become hysterical.

After receiving the mayor’s call, Borden immediately contacted the Canadian Militia. Meanwhile, Brockville’s chief of police telephoned Colonel Percy Sherwood, Commissioner of the Dominion police regarding the air invaders. At 11.15pm, Sherwood ordered Parliament Hill to be blacked out to avoid giving the raiders an easy target. While the phlegmatic Commissioner was not unduly apprehensive about the report of approaching enemy planes, he believed it expedient to take precautionary measures, including blacking-out key government buildings. The lights that illuminated the Centre block’s Victoria Tower when Parliament was in session were extinguished. The Royal Mint, which was also typically lit up at night, was similarly darkened. At Rideau Hall, home of the Governor General, the blinds were drawn. Although the Governor General was away inspecting troops in Winnipeg, his wife, the Duchess of Connaught, was in residence. Other buildings observed the black-out as news of the pending attack hit the streets. The Globe newspaper reported that the entire city of Ottawa was in darkness that night.

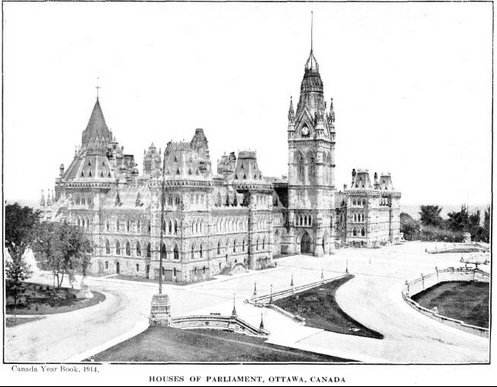

Centre Block, Houses of Parliament, Ottawa, 1914.Despite Ottawa being only 100 kilometres distant from Brockville as the crow flies, aviation experts told the Canadian authorities that it might take until midnight for the invaders to make their way to the capital owing to poor weather conditions, which included low clouds and rain. Recall that planes at that time were lucky to go much more than 100 kilometres per hour under favourable conditions. Smith Falls, Perth, and Kempville, which were on the expected flight path, were alerted, and told to keep a sharp look-out. But midnight came and went without any sign of the intruders.

Centre Block, Houses of Parliament, Ottawa, 1914.Despite Ottawa being only 100 kilometres distant from Brockville as the crow flies, aviation experts told the Canadian authorities that it might take until midnight for the invaders to make their way to the capital owing to poor weather conditions, which included low clouds and rain. Recall that planes at that time were lucky to go much more than 100 kilometres per hour under favourable conditions. Smith Falls, Perth, and Kempville, which were on the expected flight path, were alerted, and told to keep a sharp look-out. But midnight came and went without any sign of the intruders.

The next day, newspapers were full of stories on the putative air raid. The Globe’s headline screamed: “Ottawa In Darkness Awaits Aeroplane Raid. Several Aeroplanes Make A Raid Into The Dominion Of Canada.” In the streets of the capital, citizens experienced a frisson of excitement with the war apparently being brought to the city. The Ottawa Journal reported that “Ottawa feels first thrill of war,” and marvelled that usually reserved Ottawa citizens were stopping complete strangers on the street seeking news of the invaders. In the House of Commons, Sir Wilfrid Laurier rose and asked the Prime Minister for any information that he might be able to provide. Borden confirmed that he had received a telephone call from the Mayor of Brockville, and that he had communicated the news of the expected raid to the chief of the general staff, but he was “unable to give the point of departure of the aeroplanes in question.” That night, fearing that the previous night’s attack might have been aborted owing to bad weather and subsequently re-launched, government buildings were blacked out for a second night. Parliament sat as usual, but behind drawn curtains.

For two hours, Ottawa’s city council debated a motion submitted by St George Ward alderman Cunningham “that in view of the possibility of an air raid on the city hall while this august body is in session, Constable McMullen be instructed to pull down the blinds.” The Ottawa Journal wryly noted that the debate occurred under the glare of 61 electric lights which lit up the building. It also noted that the alderman frequently absented himself from the debate to climb the city hall tower to scan the skies for sight of the approaching planes so that he could be the first to warn his colleagues to take shelter in the cellar.

When no planes appeared, people started to look for other explanations. Quickly, suspicion focused on some Morristown youths, described as “village cut-ups,” who admitted to having sent up three “fireworks balloons” from the American side of the St Lawrence at about 9pm which exploded in the air above Brockville. Giving credence to this story, the remains of balloons with firework attachments were subsequently recovered from the ice on the St Lawrence two miles east of the town, as well as from the grounds of the Brockville Asylum, now called the Brockville Mental Health Centre. The ostensible reason for sending up the balloons was to commemorate the centenary of the end of the war of 1812. More likely it was a prank aimed at scaring Canadians.

Officials in Ottawa didn’t readily believe these reports. The Dominion Observatory reported that the wind that night was consistently coming from the east. It contended that as Morristown is directly opposite Brockville, any balloons sent up from the Morristown area would have travelled to the west, and certainly not in the direction the airplanes were said to have taken. The press also reported that militia authorities were in contact with Washington, and that a thorough inquiry had been set in motion to locate the airplanes’ base of operation.

Across the Atlantic in England, which had experienced its first German Zeppelin air raid just three weeks earlier, the phantom air raid on Ottawa was a source of merriment. By chance, the night after the Ottawa scare, the lights of Parliament at Westminster suddenly went out. Making a reference to the Ottawa raiders, William Crooks, Labour MP for Woolwich cheekily called out in the darkness” “Hello, they’re here!” The House of Commons cracked up with laughter.

So what really happened that Valentine’s Day night? How plausible was an attack on Ottawa?

It wouldn’t have been the first time that armed raiders had crossed the U.S. border into Canada. There were precedents. Less than fifty years earlier, the Fenians, an Irish extremist group, made a number of military forays into Canada across the U.S. border. The Ottawa Journal also claimed that German sympathizers in the United States had contemplated action against Canada during the early days of the war in 1914, going so far as to set up training bases in the United States with the objective of “making a descent upon Canada to destroy canals and railways” before being told to desist by U.S. authorities. Less than two weeks prior to the supposed air raid on Ottawa, Werner Horn, a German army reserve lieutenant, tried to blow up the Vanceboro international bridge between St Croix, New Brunswick and Vanceboro, Maine in an attempt to disrupt troop movements.

British B.E.2c, manufactured by the British Air Factor, Vickers, Bristol, circa. 1914.However, an air raid on Ottawa by German sympathizers seems highly unlikely. While on a sharp upward development trajectory, aviation was still primitive in early 1915, the first powered flight having taken place only eleven years earlier. Even at the front in France, airplanes were then mostly used for reconnaissance. Typical of that era, the British military airplane, the B.E.2c, could stay aloft for only three hours.

British B.E.2c, manufactured by the British Air Factor, Vickers, Bristol, circa. 1914.However, an air raid on Ottawa by German sympathizers seems highly unlikely. While on a sharp upward development trajectory, aviation was still primitive in early 1915, the first powered flight having taken place only eleven years earlier. Even at the front in France, airplanes were then mostly used for reconnaissance. Typical of that era, the British military airplane, the B.E.2c, could stay aloft for only three hours.

The most likely explanation is the toy balloon story, combined with a bad case of war jitters. As suggested by one of the newspapers, the searchlight beam that reportedly lit up Brockville could be explained by a fortuitous flash of lightning while the balloons were above the city. However, the fact that the Dominion Observatory was adamant in its view on the wind direction that night fuelled fears that the bombers were real.

Certain modern-day investigators have a whole different explanation—UFOs. The story of Ottawa’s phantom air raid has featured in a number of books on the paranormal, including The Canadian UFO Report: The Best Cases Revealed. To add grist to the paranormal mills, the same night Ottawa prepared for an air raid, strange lights and planes were apparently spotted over other Ontario towns.

Sources:

Colombo, John Robert, 1999. Mysteries of Ontario, Hounslow Press.

House of Commons, 1915. “Reported Appearance of Aeroplanes,” Twelfth Parliament, Fifth Session, Volume One, 15 February.

Rutkowski, Chris & Dittman, Geoff, 2006. The Canadian UFO Report: The Best Cases Revealed, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

The Globe, 1915. “Ottawa In Darkness Awaits Aeroplane Raid,” 15 February.

————————, 1915. “Were Toy balloons and not Aeroplanes!” 15 February.

The Ottawa Journal, 1915. “House To Be Dark Again To-night,” 15 February.

————————, 1915. “Wind From East; Fact That Casts Doubt On Toy Balloon Story; But It Seems Most Likely Explanation,” 15 February.

———————-, 1915. “The Air Raid That Didn’t,” 15 February.

———————–, 1915, “Brockville Statement,” 15 February.

———————–, 1915. “Laughing at Ottawa,” 16 February.

Unikoshi, Ari, 2009. The War in the Air, http://www.firstworldwar.com/airwar/summary.htm.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. 2007. “The Phantom Invasion of 1915,” Rootsweb, Quebec-Research Archives, http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/QUEBEC-RESEARCH/2007-04/1176680122.

Images:

Statistics Canada. Parliament, 1914. http://www65.statcan.gc.ca/acyb07/acyb07_2014-eng.htm.

British B.E.2c, circa 1914, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Aircraft_Factory_B.E.2.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Josephine Baker

26 August 1955

If you wanted great entertainment, especially jazz, in Ottawa during in the 1950s, you went to the Quebec side of the Ottawa River. Among the many nightclubs located there, the most prominent were probably the Standish Hall Hotel in Hull and the Gatineau Country Club in Aylmer. At these locales, one saw such legendary figures as Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Sarah Vaughn. On 26 August 1955, the curtain went up at the Gatineau Country Club on the incomparable Josephine Baker, known in her adopted France as simply “La Baker.” She was in Ottawa for a week’s engagement, her first and only visit to the nation’s capital.

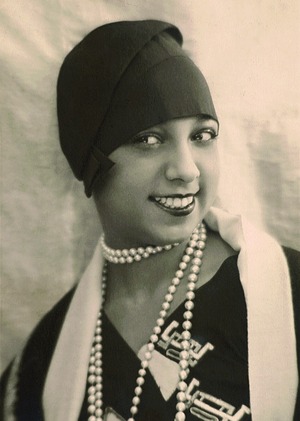

Joséphine Baker photographiée par Paul Nadar, 1930.Josephine Baker was born Freda Josephine McDonald in 1906 in St. Louis, Missouri, the daughter of a washerwoman and a vaudeville drummer who quickly abandoned his young family. A poor black girl growing up in the United States at its segregationist worst faced bleak prospects. As a young child she was cleaning houses for rich white people. By age thirteen she was waiting tables, and by age fifteen was already twice married and twice divorced. The only thing she got out of the second marriage, which lasted but a month, was her surname “Baker” which she kept throughout her life despite two more marriages…and two more divorces.

Joséphine Baker photographiée par Paul Nadar, 1930.Josephine Baker was born Freda Josephine McDonald in 1906 in St. Louis, Missouri, the daughter of a washerwoman and a vaudeville drummer who quickly abandoned his young family. A poor black girl growing up in the United States at its segregationist worst faced bleak prospects. As a young child she was cleaning houses for rich white people. By age thirteen she was waiting tables, and by age fifteen was already twice married and twice divorced. The only thing she got out of the second marriage, which lasted but a month, was her surname “Baker” which she kept throughout her life despite two more marriages…and two more divorces.

Despite this unprepossessing start in life, young Josephine Baker found her calling as an entertainer. In 1919, she joined a black vaudeville company. Two years later she came to New York, then in the midst of the Harlem Renaissance, to play in The Dixie Steppers. While initially judged too black to be in the chorus, she got her chance when a chorus girl got sick. She played the comic role of the inept dancer at the end of the chorus line who initially bungles the routine only to blossom into the troupe’s finest dancer.

Seizing an opportunity to dance in Paris, she voyaged to France in 1925 to join La Revue Nègre. Paris was a revelation. Here, a black woman could stay at the finest hotels and dine in the best restaurants without discrimination. Instead of being considered a second-class citizen or worse, she was admired and welcomed.

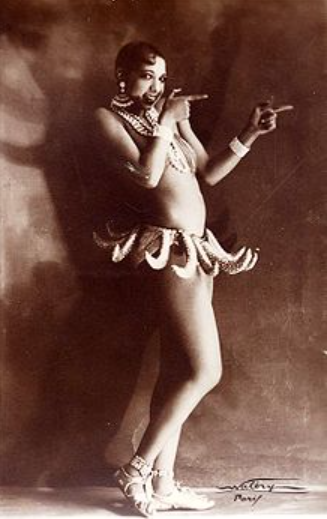

After touring Europe with La Revue Nègre, she joined the famous Folies Bergère. She was a huge success, her famed cemented by a dance in which she wore only a skirt made of sixteen, strategically placed bananas. Jaded French audiences had never seen such a performance. Its raw sensuality stunned them. By 1927, at the age of only twenty-one, she was the highest paid female entertainer in the world.

Josephine Baker, 1927, Folies Bergère, Un Vent de Folie, Waléry, Paris.She became a film star, appearing in Zouzou (1934) and Princess Tam-Tam (1935), as well as several other films. Princess Tam-Tam was banned in the United States. It was not clear what shocked white America more, showing a black woman in a relationship with a white man, or a black woman cast in the lead role. She became an inspiration to oppressed African Americans.

Josephine Baker, 1927, Folies Bergère, Un Vent de Folie, Waléry, Paris.She became a film star, appearing in Zouzou (1934) and Princess Tam-Tam (1935), as well as several other films. Princess Tam-Tam was banned in the United States. It was not clear what shocked white America more, showing a black woman in a relationship with a white man, or a black woman cast in the lead role. She became an inspiration to oppressed African Americans.

By the mid-1930s, her performance style began to change. Out went the primitive, catlike eroticism of her youth in favour of the mature, French chanteuse in the style of Edith Piaf. Parisian audiences adored her.

In 1935, Baker returned briefly to the United States to perform in New York in the famous Ziegfeld Follies. It was not a happy experience. Now a star, she was allowed to stay in one of New York’s big hotels, but only if she used the service entrance. Her performance, which included dancing with white men, was still beyond the pale of even a liberal New York audience. After newspapers insulted her and made racial comments, she returned disheartened to Paris.

In 1937, she married a wealthy Frenchman, Jean Lion. While the marriage didn’t last, she became a naturalized French citizen, renouncing her American citizenship. She famously said that the Eiffel Tower “looked very different from the Statue of Liberty, but what does that matter? What was the good of having a statue without the liberty?”

When war came, Baker took on a new role as spy and resistance fighter. Using her fame as a shield, she smuggled secret messages amongst her sheet music to the Free French. Later, after fleeing to North Africa, she performed for Allied soldiers. She insisted that she would only perform in front of integrated audiences. After the war, the French government awarded Baker the Resistance Medal with Rosette and made her a Chevalier d’honneur.

She also took on a new persona, that of a grande dame. Once famed for dancing in skimpy costumes, she now showcased the finest in French fashion, wearing designer gowns from Christian Dior and other leading fashion houses. In 1947, she married Jo Bouillon, a French orchestra leader.

She tried another return to the United States in 1951. She again insisted that she would only perform in front of non-segregated audiences. Her U.S. tour, which began in Miami, was a great success until she was denied service at New York’s prestigious Stork Club. After making an official complaint to the Club, she got into a battle of words with the famed American journalist Walter Winchell who accused her of being a communist. This was at the height of Senator McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade that led to hundreds of American entertainers being blacklisted. Baker was banned from the United States for nine years.

Josephine Baker, March on Washington, 1963, Château des Milandes.Through the 1950s, Baker and Jo Boullion raised a group of dozen adopted children of all races which they called The Rainbow Tribe at Baker’s chateau, Les Milandes, and 700-acre estate in the Dordogne region of France. It was Baker’s effort to demonstrate that people of all nationalities could live together in peace and harmony.

Josephine Baker, March on Washington, 1963, Château des Milandes.Through the 1950s, Baker and Jo Boullion raised a group of dozen adopted children of all races which they called The Rainbow Tribe at Baker’s chateau, Les Milandes, and 700-acre estate in the Dordogne region of France. It was Baker’s effort to demonstrate that people of all nationalities could live together in peace and harmony.

Maintaining a fifteenth-century chateau while raising such a large family became even more onerous when Baker’s fourth marriage failed. Never a good business person, and very generous, Baker ran up large debts. Eventually, she lost her chateau to creditors, and had to return to the stage to repay her debts. Helped by Princess Grace of Monaco, she and her Rainbow Tribe took up residence in a home in Monaco.

In 1963, Baker was invited to join the March on Washington with Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders. Wearing her French military uniform with all of her medals, she appeared on the podium where she gave a short speech of support. She said that it was “the happiest day of her life.”

That summer of 1955, when Josephine Baker came to Ottawa, the great entertainer stayed at the Château Laurier Hotel while she performed at the Gatineau Country Club. Travelling with her were her French maid, Miss Jeanette Renaudin, her musical director, Mikos Bartek, nine trucks of clothes, and a photograph of her husband, Jo Bouillon. Press reports said that her wardrobe was insured for $250,000 ($2.5 million in today’s money).

She started her visit with a press conference and special performance at the Press Club in Ottawa a few days before the official start of her gig. Dressed in a slinky black dress, she wowed the journalists in the room who wondered whether she would have a wardrobe malfunction. “If accidents happen, well, c’est la mode,” she said. Bob Blackburn, the Citizen reporter, said there was no describing her, “even the most extravagant adjectives can’t do her justice.”

Talking about her decision to go to Paris back in 1925, Baker told that journalists that she had been looking for more freedom to express herself. In the United States, the only thing a black woman could do in show business was to wear a bandana on her head. She hoped that her example would open doors in other fields for other African Americans.

She also claimed to have been one of the first entertainers to appear before a television camera. The event occurred in 1935 in the BBC Studios in England. She said that she was put in a little cubicle with her face painted white since that was the only way she could be seen on the equipment of that time. “Image me with a white face!” she exclaimed.

Advertisement, Ottawa Citizen, 24 August 1955.At the Press Club, she sang in both French and English, performing her old favourites such as J’attendrai. There was a lot of focus on her wardrobe for her performance which ranged from a simple white tailored blouse to extravagant evening gowns. One gown, “a sheath-like creation” was decorated in an oyster shell pattern. As she walked, the shells opened to reveal smaller shells and little pearls.

Advertisement, Ottawa Citizen, 24 August 1955.At the Press Club, she sang in both French and English, performing her old favourites such as J’attendrai. There was a lot of focus on her wardrobe for her performance which ranged from a simple white tailored blouse to extravagant evening gowns. One gown, “a sheath-like creation” was decorated in an oyster shell pattern. As she walked, the shells opened to reveal smaller shells and little pearls.

Other engagements in Ottawa included a visit to the French Embassy and radio interviews in both languages.

On opening night in the Carnival Room at the Gatineau Country Club, Josephine Baker received a standing ovation. She wowed the audience with her showmanship, her informal bantering with the audience, and her ability to sing straight from the heart. Among the many songs she sung were Unchained Melody and Begin the Beguine. She modelled gowns by Christian Dior, Jean Dessès, and others. The Ottawa Citizen reported “Here is an entertainer who deserves all the superlatives one can name. She will live in your memory for many years to come. This is Josephine Baker, the incomparable.”

Josephine Baker, entertainer sans pareil, World War II hero and civil rights leader, died in April 1975 at the age of 68, struck down by a cerebral hemorrhage, one day after opening a new show at the Bobino Theatre in Paris celebrating fifty years in show business. A week later, 20,000 people attended her funeral at La Madaleine in Paris. The French government gave her a twenty-one-gun salute. She was buried with full military honours in le Cimetière de Monaco in Monaco.

An inspiration to many, including Beyoncé, today’s megastar, Josephine Baker once said “Surely the day will come when colour means nothing more than the skin tone, when religion is seen uniquely as a way to speak one’s soul, when birth places have the weight of the throw of the dice and all men are born free, when understanding breeds love and brotherhood.”

We have a long way to go.

Sources:

BBC Wales, 2006. Josephine Baker: The First Black Superstar, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ggb_wGTvZoU. YouTube.

Caranvates, Peggy, 2015. The Many Face of Josephine Baker: Dancer, Singer, Activist, Spy, Chicago Review Press, Chicago, Illinois.

Château et jardins des Milandes, Demure de Josephine Baker, 2020. Josephine Baker, Tribute to a Great Lady, https://www.milandes.com/en/josephine-baker/.

Official Site of Josephine Baker, 2020. https://www.cmgww.com/stars/baker/.

Ottawa Citizen, 1955. “They Call Her Fabulous But That Is Inadequate,” 24 August.

——————, 1955. “Josephine Baker Has Gala Wardrobe,” 25 August.

——————, 1955. “Standing Ovation For Baker At Gatineau,” 27 August.

Ottawa Journal, 1955. “Toast Of Paris, Josephine Baker Entertains Press,” 24 August.

——————-, 1975. “Singer, 68, dies in Paris,” 12 April.

——————-, 1955. “Final Tribute for Josephine,” 16 April.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Meet Me at Murphy's

29 January 1983

One of the greatest of the shopping emporiums that used to line Sparks Street, once the commercial heart of Ottawa, was Murphy-Gamble’s. It ranked amongst the finest Canadian department stores, and had a well-earned reputation for quality merchandise. The store attracted the custom of the city’s elite, including governors general and prime ministers. But its particular claim to fame was its restaurant, the Rideau Room, located on the fifth floor of the building at 118-124 Sparks Street. It was the only Ottawa’s department store that featured a dining room. Here, one could enjoy fine food accompanied by a live band, sometimes a trio, sometimes a seven-piece orchestra. It also served high tea each afternoon to weary customers who needed to catch their breath before renewing their assault on the store’s many departments. “Meet Me At Murphy’s” became an oft-heard refrain.

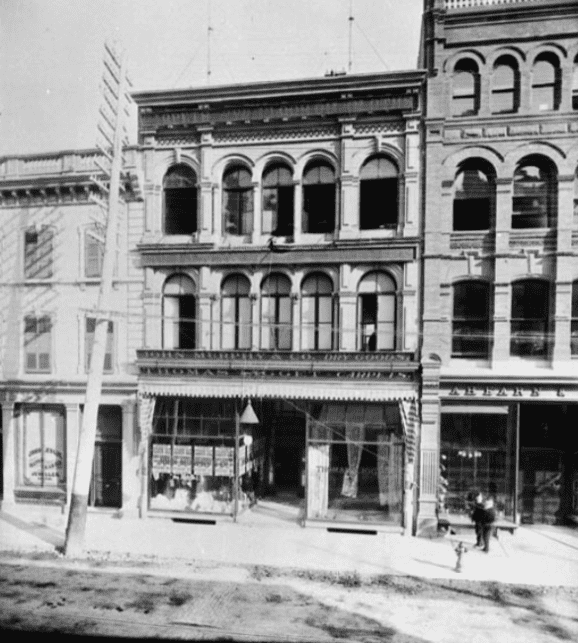

John Murphy Company, 66-68 Sparks Street, August 1892, Topley Studios, Library and Archives Canada, 138219.Murphy’s roots actually begin in Montreal where in 1867, John L. Murphy opened a dry-goods store on Catherine Street. In 1890, Murphy expanded to Ottawa, buying Argyle House, a dry-goods store located at 66-68 Sparks Street from David Gardner who had himself acquire the entire stock of Argyle House for 61 cents on the dollar in a bankruptcy sale. He also leased the premises for a few months to clear the stock. Argyle House had been known for its high-end merchandise and for catering to Ottawa’s elite. The store had originally been opened in the early 1870s by James Russell.

John Murphy Company, 66-68 Sparks Street, August 1892, Topley Studios, Library and Archives Canada, 138219.Murphy’s roots actually begin in Montreal where in 1867, John L. Murphy opened a dry-goods store on Catherine Street. In 1890, Murphy expanded to Ottawa, buying Argyle House, a dry-goods store located at 66-68 Sparks Street from David Gardner who had himself acquire the entire stock of Argyle House for 61 cents on the dollar in a bankruptcy sale. He also leased the premises for a few months to clear the stock. Argyle House had been known for its high-end merchandise and for catering to Ottawa’s elite. The store had originally been opened in the early 1870s by James Russell.

The new John Murphy & Company store prospered under the management of Samuel Gamble, the company’s first vice-president who also happened to be John Murphy’s son-in-law. In 1904, John Murphy, now seventy years of age, sold his Montreal store to Robert Simpson Company of Toronto. The store continued to operate under the well-respected John Murphy & Company name. This left the Ottawa branch, now a stand-alone operation, to find a new name. In recognition of the success achieved under Samuel Gamble’s direction, the Murphy, Gamble Company was born. John Murphy continued to act as an advisor to the firm, his knowledge being invaluable. During his career as a merchant, he had made more than 100 ocean crossings to buy quality goods from European fashion houses. At this time, the three-storey building at 66 Sparks Street was expanded back towards Queen Street, thereby increasing the selling space by one-third.

Murphy-Gamble Co at 118-124 Sparks Street, circa. 1955. The Centre Cinema next door is showing a double feature of Black Pirates and Thunder Pass which were both released in 1954. Notice the old Ottawa Citizen building on the right. Rankly.com.In 1910, the company expanded again. A five-storey store was constructed at 118-124 Sparks Street, the former site of the Brunswick Hotel. The new store opened in early January 1910. The last day of trading out of the old premises proved to be memorable. So many shoppers, mostly women, crowded into the store to snap up merchandise on sale that store staff were overwhelmed. Police had to be called in to control the enthusiastic shoppers. For an hour and a half, the doors were locked with “blue coats” on guard to repel would-be bargain hunters from storming inside. The next day, Murphy-Gamble’s new premises were also swamped by shoppers wanting to get a first glimpse at the new department store. That opening day, uniformed boys assisted ladies from their cars and carriages into and out of the emporium.

Murphy-Gamble Co at 118-124 Sparks Street, circa. 1955. The Centre Cinema next door is showing a double feature of Black Pirates and Thunder Pass which were both released in 1954. Notice the old Ottawa Citizen building on the right. Rankly.com.In 1910, the company expanded again. A five-storey store was constructed at 118-124 Sparks Street, the former site of the Brunswick Hotel. The new store opened in early January 1910. The last day of trading out of the old premises proved to be memorable. So many shoppers, mostly women, crowded into the store to snap up merchandise on sale that store staff were overwhelmed. Police had to be called in to control the enthusiastic shoppers. For an hour and a half, the doors were locked with “blue coats” on guard to repel would-be bargain hunters from storming inside. The next day, Murphy-Gamble’s new premises were also swamped by shoppers wanting to get a first glimpse at the new department store. That opening day, uniformed boys assisted ladies from their cars and carriages into and out of the emporium.

Reportedly, the new store cost $175,000 to build; no expense was spared in its construction and its fittings. As far as possible, contracts and subcontracts were awarded to local Ottawa firms. Its architect was Ottawa’s Colborne Powell Meredith, it’s builder, Frederick W. Carling. The building, apparently one of the first of its kind in eastern Ontario, was constructed of reinforced concrete, a new method at that time. It also boasted what has been described as “Chicago-style glazed curtain wall façades” on both its Sparks and Queen Street sides. The pillars holding up the five storeys were also made of concrete, reinforced with steel rods, as were the stairways. There were hardwood floors throughout. The building was deemed fire proof, and was equipped with automatic fire doors and hoses on each floor. It was the first building in the city to carry electricity and lighting through underground conduits. The new edifice was called the Carling Block, presumably in honour of its builder.

On the basement level, which opened onto Queen Street, there was a high-class grocery store. There were windows displays along the entire façade. To one side was an entrance and a passageway for receiving goods. Lockers and toilets for male employees were located on this floor, The Sparks Street entrance, which was covered by a marquee, was to be found on the first, or ground floor. All interior fittings on this floor were made of mahogany. Window displays ran along Sparks Street. Two public telephones were located here for the use of customers. The women’s and men’s clothing departments were on this floor. The millinery and mantles department were found on the second floor. Fittings on this floor were made of oak. To the rear were offices; dressing rooms were located on the sides. A spacious stairway led from the main floor to an overhead gallery, or ladies’ waiting room, called “The Mezzanine.” On the third floor was the carpet, curtains and draperies department, along with customers’ washrooms. The fourth floor was devoted to manufacturing purposes, while the fifth floor was initially used for storage and bathroom facilities for female staff. Later, the fifth floor became the site of the “Tea Rooms” and later the much-loved “Rideau Room” dining room.

Samuel Gamble died in 1913 and the management of Murphy-Gamble’s passed first to Mr. J.T. Hammill and then to Mr. S.L.T. Morrell. In 1925, James L. Murray, and his two sons, Walter L. Murray and G. Scott Murray, purchased Murph-Gamble’s. The Murrays operated a similar business in Hamilton, Ontario called Murray Sons, Ltd. The two Murray sons moved to Ottawa to manage the Ottawa firm which continued to trade under the Murphy-Gamble marque. The firm thrived under the new management. Two more floors at the back of the store and an elevator were added in 1948. The firm also established buying offices in all the major cities of Europe, as well as in Mexico and the Far East.

On staff at Murphy-Gamble’s was a master tailor and dress designer, Ernest Gordon. A Gordon gown was a much sought-after attire for gala events. Reportedly, Princess Juliana of the Netherlands bought a Gordon gown. Gordon died in 1948, having worked at Murphy’s for thirty-three years.

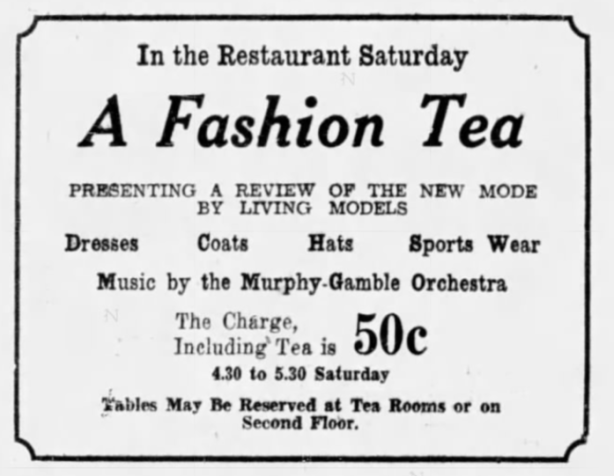

Advertisement for Tea and a Modelling Show, Ottawa Citizen, 26 September 1927.Christmas was a special time of the year at Murphy-Gamble’s. A fifty-foot Christmas tree was installed by the stairwell each year until later renovations made this impossible. A store choir sang carols every day during the week leading up to Christmas. Instead of Santa Claus coming to the store’s toy department, a series of parties was held for children in the Rideau Room where Santa gave a gift to every child. Easter was also special, bringing a visit from the Easter Bunny who handed out candy to the kiddies along with a copy of the Easter Bunny story.

Advertisement for Tea and a Modelling Show, Ottawa Citizen, 26 September 1927.Christmas was a special time of the year at Murphy-Gamble’s. A fifty-foot Christmas tree was installed by the stairwell each year until later renovations made this impossible. A store choir sang carols every day during the week leading up to Christmas. Instead of Santa Claus coming to the store’s toy department, a series of parties was held for children in the Rideau Room where Santa gave a gift to every child. Easter was also special, bringing a visit from the Easter Bunny who handed out candy to the kiddies along with a copy of the Easter Bunny story.

Murphy’s was also known for going the extra mile for its customers. Reportedly, a bride-to-be asked Murphy’s to bake her wedding cake, just as the firm had done for her mother and grandmother before her. There was one hitch. The bride lived in the North West Territories. Undeterred, Murphy’s delivered the cake via a military plane and dog sled!

Murphy-Gamble Company stayed in the Murray family for close in fifty years. In 1972, now under the presidency of Russell Boyce, the son-in-law of Scott Murray, the venerable Ottawa landmark was sold to Robert Simpson Company, the same company that purchased the original family store in Montreal in 1904. All 300 of Murphy-Gamble’s staff were re-hired. The Murphy-Gamble sign came down to be replaced by Simpson’s.

Robert Simpson Company logo.Simpson’s operated out of the 118-124 Sparks Street location for eleven years. At the end of 1982, Simpson’s, now owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company, announced that the Sparks Street store would close owning to low profit margins. The Ottawa Citizen said that shoppers were like “mourners at an Irish wake.” On 29 January 1983, Simpson’s closed its doors for a last time with the loss of 85 permanent and 150 part-time jobs. The company published a final “Thank You” to its loyal Ottawa customers. The closure of the store after almost seventy-five years of business under various owners marked the end of a retail tradition. It left only the budget-conscious Zellers remaining as the last department store on Sparks Street until it too closed in 2013.

Robert Simpson Company logo.Simpson’s operated out of the 118-124 Sparks Street location for eleven years. At the end of 1982, Simpson’s, now owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company, announced that the Sparks Street store would close owning to low profit margins. The Ottawa Citizen said that shoppers were like “mourners at an Irish wake.” On 29 January 1983, Simpson’s closed its doors for a last time with the loss of 85 permanent and 150 part-time jobs. The company published a final “Thank You” to its loyal Ottawa customers. The closure of the store after almost seventy-five years of business under various owners marked the end of a retail tradition. It left only the budget-conscious Zellers remaining as the last department store on Sparks Street until it too closed in 2013.

Bank of Nova Scotia, Sparks Street Branch, the former Murphy-Gamble building, 2017, Photo credit: Nelia.The former Murphy-Gamble/Simpson’s building was acquired by the Bank of Nova Scotia in January 1983. After extensive renovations, the former department store was converted into a bank branch.

Bank of Nova Scotia, Sparks Street Branch, the former Murphy-Gamble building, 2017, Photo credit: Nelia.The former Murphy-Gamble/Simpson’s building was acquired by the Bank of Nova Scotia in January 1983. After extensive renovations, the former department store was converted into a bank branch.

Sources:

Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada, 1800-1950, Meredith, Colborne Powell, http://www.dictionaryofarchitectsincanada.org/node/1483.

Daily Citizen, 1890. “$68,000 Bankrupt Stock of Dry Goods,” 17 May.

Heritage Ottawa, 1983. Newsletter, February.

Ottawa Citizen, 1972. “Fond farewell to Murphy’s,” 24 June.

—————-, 1982. “Simpsons’ loyal friends already mourning loss,” 31 December.

Ottawa Evening Citizen, 1910. “Last Day Was Memorable One,” 10 January.

—————————–, 1925, “Murphy-Gamble, Ltd. Store Acquired By Hamilton Firm,” 1 September.

—————————–, 1952. “Walter M. Murray Is New Head of Murphy-Gamble,” 18 November.

Evening Journal, 1890. “Argyle House,” 18 December.

Ottawa Journal, 1904. “Retail Dry Goods Deal,” 21 December.

——————-, 1910. “Magnificent New Addition To Ottawa’s Commercial Buildings,” 26 February.

Urbsite, 2012. Murphy-Gamble, Sparks’ Department Stores III, 14 May.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Battle of the Hatpins

7 January 1916

The British North America Act, which established the Dominion of Canada in 1867, was an ambitious piece of legislation. In addition to uniting the Province of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, the Act was crafted to meet the aspirations of its English and French communities as well as to guarantee the religious educational rights of Roman Catholics and Protestants.

The Act split the Province of Canada into the overwhelmingly English-speaking Ontario, and the predominantly French-speaking Quebec. Each could now exercise a wide range of powers in their respective jurisdictions without having to compromise with the other—a problem in the old Province of Canada where both, then called Canada West and Canada East, were equally represented in the legislature. With the English-speaking population growing rapidly relative to the French-speaking population, it was not politically feasible to maintain the original parity of seats in the House of Assembly between the two linguistic groups. The establishment of a separate Quebec ensured that French-speakers remained in control of their traditional territory within the Dominion.

Section 133 of the Act also guaranteed that both English and French would be used in the parliaments of Canada and Quebec as well as in federal and Quebec courts. Section 93 additionally recognized educational rights under which Roman Catholics in Ontario and Protestants in Quebec could attend their own schools distinct from the public-school systems of the two provinces.

The BNA Act was not perfect, however. Education, which was a provincial responsibility, was based on religion not language. While most francophones were Roman Catholic, not all Roman Catholics were francophone. This lack of congruence and the fact that the BNA Act did not speak to the language of instruction in delivering education were to become a flashpoint in English-French relations in Canada.

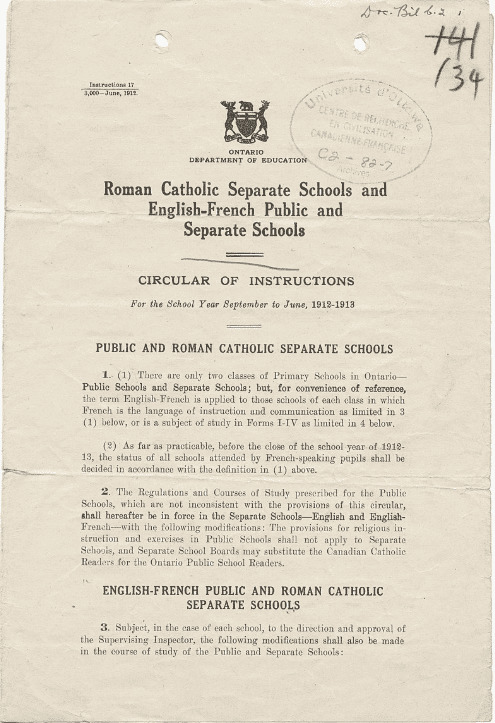

Cover page of Regulation 17 that restricted the use of French as the language of instruction in Ontario’s elementary schools, 1912, University of Ottawa.For many years after Confederation, minority French-speaking Ontarians attended separate elementary schools where French was used as the language of instruction. However, English-speaking Ontarians increasingly felt threated by the migration of French-Canadians into Ontario, especially into the eastern part of the province. By the end of the nineteenth century, the francophone population of Ontario had roughly doubled to 10 per cent. While English-speakers had to tolerate the use of French in Quebec and at the federal level given the BNA Act, they considered Ontario to be a British province in a British country. A growing French presence in Ontario was something that many could not abide.

Cover page of Regulation 17 that restricted the use of French as the language of instruction in Ontario’s elementary schools, 1912, University of Ottawa.For many years after Confederation, minority French-speaking Ontarians attended separate elementary schools where French was used as the language of instruction. However, English-speaking Ontarians increasingly felt threated by the migration of French-Canadians into Ontario, especially into the eastern part of the province. By the end of the nineteenth century, the francophone population of Ontario had roughly doubled to 10 per cent. While English-speakers had to tolerate the use of French in Quebec and at the federal level given the BNA Act, they considered Ontario to be a British province in a British country. A growing French presence in Ontario was something that many could not abide.

One way of ensuring that English remained predominant was through assimilation. In 1885, English became a compulsory subject in all elementary schools in Ontario. Five years later, English became the language of instruction in all schools except where the use of English was impracticable, i.e. when students were unable to understand English. Using this exemption, bilingual separate schools continued to teach in French.