James Powell

Lord Stanley’s Cup

18 March 1892

Each spring as winter’s snows begin to recede, the thoughts of Canadians turn to the Stanley Cup. One of the oldest sporting trophies in the world, the Cup is the symbol of hockey supremacy in North America. Its provenance is well known; it was purchased and given to the hockey community by Lord Stanley of Preston, Canada’s Governor General, in 1892. What is less well known is that Ottawa featured prominently in the Cup’s story. It was in Ottawa that Stanley let it be known his intention to provide a championship trophy. As well, during his vice-regal tenure in the nation’s capital, the Governor General, an avid hockey fan, and his equally hockey-mad children, did much to make hockey Canada’s national game. The Ottawa Hockey Club also played in the first Stanley Cup championship game.

The sport of ice hockey has a long history. It probably originated in “ball and stick” games played by both Europeans and natives peoples in North America. Shinny, an early form of ice hockey, was played on rivers or ponds in Nova Scotia during the early nineteenth century. Shinny could involve scores of players on each team, using a wooden puck, one-piece hockey sticks and hockey skates. Modern ice hockey dates from early 1875 when Halifax native James Creighton organized an indoor game at the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal. Given the constrained skating surface, teams were limited to nine per side (reduced to seven in 1880). Played with a flat wooden disk using hockey sticks made by Mi’kmaq carvers from Nova Scotia, the game used “Halifax Rules” that included a prohibition on the puck leaving the ice and no shift changes. The match was an overwhelming success for both its participants and its appreciative audience.

In response to growing interest in the sport in central Canada, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC) was formed in 1886 with five teams, four from Montreal (the Victorias, the Crystals, the Montreal Hockey Club, and McGill College) and one from Ottawa, the Ottawa Hockey Club, known as the Ottawas. The Ottawas were established in 1883 and were a frequent participant in hockey games held during the Montreal Winter Carnival during the 1880s.

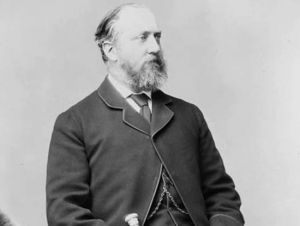

Lord Stanley of Preston arrived in Canada in 1888 to take up his position as the Dominion’s sixth Governor General. An avid sportsman, he was introduced to the game of ice hockey in February 1889 when he and members of his family, including his eldest son Edward and daughter Isobel, visited the Montreal Winter Carnival. Arriving while a hockey game was in progress—play was temporarily halted on his arrival—the Governor General, his family and friends watched the Montreal Victorias defeat the Montreal Hockey Club.

Lord Stanley was instantly hooked on the game. He quickly built an outdoor rink at Rideau Hall, his Ottawa residence, for the use of his family and staff. He took to the ice himself, though he apparently got into some trouble for skating on the Sabbath. In March 1889, his Rideau Hall rink was the site of what is believed to be the first woman’s hockey match between a Government House team on which Isobel Stanley played, and a Rideau ladies team. Her brothers, Edward, Arthur, Victor and Algernon, were also keen hockey players. They played with various official aides, MPs and senators on a team dubbed the “Rideau Rebels,” but more formally known as the Vice-Regal and Parliamentary Hockey Club. The Rebels played exhibition games throughout eastern Ontario including Kingston and Toronto that helped to popularize the game. The fact that Lord Stanley had placed his vice-regal stamp of approval on the game was another important factor in hockey’s rapid acceptance as Canada’s national winter sport.

In 1890, Lord Stanley’s son, Arthur, along with two team mates from the Rideau Rebels, helped create the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA), composed of thirteen teams from Toronto, Kingston and Ottawa, later joined by a team from Lindsay. Today, the OHA oversees junior hockey in Ontario. During the late nineteenth century, long before there was a National Hockey League and professional players, OHA teams represented the cream of Ontario hockey. The Ottawa Hockey Club team played in both the OHA and the AHAC centred in Montreal.

The Stanley Cup dates from 18 March 1892. That night, a celebratory dinner for members of the Ottawa Hockey Club was held at the Russell House Hotel. The Russell House was Ottawa’s top watering hole at the time, standing at the north-eastern corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets, roughly between today’s National War Memorial and the National Arts Centre. The Ottawas had just finished a championship year, winning the Cosby Cup of the OHA and holding the AHAC championship from January to early March before losing it to the Montreal Hockey Club. The Ottawa Evening Journal noted that the back of the dinner’s menu cards recorded the achievements of the team: nine championship matches won to only a single defeat, during which the team scored 53 goals “against the best teams in Canada,” allowing only 19 goals the other way.

Accounts differ on the number of people at the dinner. The Journal reported that there were between 70 and 80 present, while the Montreal Gazette said that about 200 admirers attended. The latter, larger number probably reflected the addition of the ladies who joined the men after the dinner for “ices.” Mr J.W. McRae, president of the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association, the senior umbrella sporting association to which the Ottawa Hockey Club was affiliated, presided over the soirée, while the band of Governor General’s Foot Guards provided suitable musical entertainment.

At about 10pm, after the loyal toast to Queen Victoria, followed by another toast to the health of the Governor General, Lord Kilcoursie, an aide to Lord Stanley, rose to reply on behalf of the Governor General who had been unable to attend the evening’s event. After thanking the gathering, Kilcoursie read out a letter from Stanley. Dated 18 March 1892, it said:

I have for some time past been thinking that it would be a good thing if there were a challenge cup which should be held from year to year by the champion hockey team in the Dominion. There does not appear to be any such outward and visible sign of a championship at present, and considering the general interest which matches now elicit, and in the importance of having the game played fairly and under rules generally recognized, I am willing to give a cup, which shall be held from year to year by the winning team.

I am not quite certain that the present regulations governing the arrangement of matches give entire satisfaction, and it would be worth considering whether they could not be arranged so that each team would play once at home and once at the place where their opponents hail.

The letter was enthusiastically received by the partisan hockey crowd.

Kilcoursie also revealed that the Governor General had commissioned his former military secretary, Captain Charles Colville of the Grenadier Guards, who had recently returned to Britain, to purchase an appropriate trophy on Stanley’s behalf.

After a series of more toasts, including one to the Ottawa Hockey team as well as others to members of the league, the Press and the Ladies, the dinner broke up at about midnight, though not before many songs were sung. In particular, Lord Kilcoursie entertained the party goers by singing a “ditty” titled The Hockey Men that he had personally composed to honour the members of the Ottawa Hockey Club. The first two verses went:

There is a game called hockey

There is no finer game

For though some call it ‘knockey’

Yet we love it all the same.

This played in His Dominion

Well played both near and far

There’s only one opinion

How ’tis played in Ottawa.

At the end, the crowd gave “a rousing chorus, rendered in stentorian style” according to the Journal, repeating the third verse of the eighteen-verse poem:

Then give three cheers for Russell

The captain of the boys.

However tough the tussle

His position he enjoys.

And then for all the others

Let’s shout as loud we may

O-T-T-A-W-A!

Over in England, Captain Colville purchased Stanley’s Cup from the London silversmiths G.R. Collis of Regent Street for the sum of 10 guineas (ten pounds, ten shillings). As one pound was worth $4.8666 in Canadian money, this was the equivalent to $51.10, a considerable sum in 1892. On one side of the silver bowl with a gilt interior was engraved “Dominion Hockey Challenge Trophy,” while the inscription “From Stanley of Preston” with his family coat of arms was on the other. The Cup arrived in Ottawa the end of April 1893 and was entrusted to two trustees, Sheriff John Sweetland and Philip D. Ross.

The original Stanley Cup. The silver bowl stands 19cm high and has a diameter of 28.5 cm and a circumference of 89 cm

The original Stanley Cup. The silver bowl stands 19cm high and has a diameter of 28.5 cm and a circumference of 89 cm

Library and Archives CanadaThe trustees announced that the Cup would henceforth be called the “Stanley Cup” in honour of its donor and, as specified by Lord Stanley, it would be a “challenge” cup. In other words, the Cup would be open for all. Any team could challenge the holder of the Cup for the championship title though the two trustees had the final say on whether a challenge would be accepted. Other conditions included the requirements that a winning team keep the trophy “in good order,” that each winning team (except for the first winner) would engrave its name on a silver ring fixed to the trophy at its own cost, that the Cup was not the property of any one team, and that in case of doubt over who was rightly the champion team in the Dominion, the trustees’ decision was final.

Unfortunately, the presentation of the first Stanley Cup in May 1893 was mired in controversy. The Montreal Amateur Athletic Association (MAAA) was awarded the trophy by virtue of its affiliated Montreal Hockey Club's first place standing in the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada league. The trustees duly engraved Montreal AAA on the Cup, and arranged for Sheriff Sweetland to present the trophy at the Association’s Annual General Meeting. The president of the Montreal Hockey Club, James Stewart, who was also a player on the team, was asked to attend the Annual General Meeting to receive the Cup. However, Stewart refused to accept the trophy believing that the Montreal Hockey Club should be recognized as the trophy's winner not the MAAA. Not willing to embarrass the Governor General’s emissary, James Taylor, the president of the MAAA, accepted the Cup from Sweetland on behalf of the MAAA.

The spat between the MAAA and the Montreal Hockey Club went on for some months. After a number of letters between the two organizations and between Sweetland and Ross, a reconciliation was achieved, and the Stanley Cup was finally transferred to the Montreal Hockey Club in time for the 1894 championship game. Held in late March of that year with the Ottawa Hockey Club, their long-time rivals, the match attracted some five thousand cheering fans to the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal. After Ottawa took a one-goal lead, the Montreal team stormed back with three unanswered goals to win the game 3-1 and the Cup. Later, the neutral words “Montreal 1894” were engraved on the Cup to avoid any hard feelings between the parent Montreal Association and its related Montreal Hockey Club.

Sadly, Lord Stanley, the man behind the Cup, was not there to witness the first challenge match for his trophy. He had returned home the previous summer to take up the duties as the 16th Earl of Derby following the death of his elder brother.

Sources:

Batten, Jack, Hornby Lance, Johnson, George, Milton Steve, 2001. Quest for the Cup, A History of the Stanley Cup Finals 1893-2001, Jack Falla, Genera Editor, Thunder Bay Press: San Diego.

Hockey Hall Of Fame, 2016. Stanley Cup Journal.

Jenish, D’Arcy, 1992. The Stanley Cup: A Hundred Years of Hockey At Its Best, McClelland & Stewart Inc.: Toronto.

McKinley, Michael. 2000. Putting A Roof On Winter, Greystone Books: Vancouver.

Montreal, Gazette (The), 1892. “Lord Stanley Promises To Give A Championship Cup,” 19 March.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1892. “Stars of the Ice.” 19 March.

————————————, 1893. “The Stanley Cup.” 1 May.

Shea, Kevin & Wilson, John J., 2006. Lord Stanley: The Man Behind The Cup, Fenn Publishing Company Ltd: Bolton, Ontario.

Vaughan, Garth, 1999. The Birthplace of Hockey.

Wikipedia, 1891-92, 2014. Ottawa Hockey Club Season.

Images:

Lord Stanley of Preston, 1889. Topley Studio/Library and Archives Canada, PA-027166.

The Stanley Cup, Library and Archives Canada.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Dawson City Challenge

16 January 1905

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the rules of ice hockey were considerably different than they are today. For one thing, a team had seven players on the ice instead of the modern six. The extra player was known as the “rover.” The game itself was divided into two, thirty-minute halves, instead of three, twenty-minute periods. Forward passes were illegal. Similar to rugby, the puck-handler who found his progress blocked was forbidden to pass the puck forward to an open team mate. Pity the poor goalie too. He was virtually indistinguishable from other players, wearing little or no padding. At best, his shins were protected by cricket pads. The other team members didn’t have it easy though; line changes were a thing of the future.

Who could compete for the Stanley Cup was also very different. Instead of the Eastern and Western Conference champions of the National Hockey League playing in a best-of-seven series, the Cup was a “challenge” cup for amateur play. A hockey club, usually the winner of some league play, challenged the Cup holder for the trophy, typically in a best of three game series, or a two-game, total goals series. The winning team also got to take home the Cup, and only relinquished the trophy upon its defeat by a challenger.

In the fall of 1904, the reigning Stanley Cup champions, Ottawa’s Silver Seven, the forerunners of the Ottawa Senators, were challenged by an upstart team from Dawson City, Yukon called the Dawson City Nuggets, or sometimes the Dawson City Klondikers. The Cup challenge was organized by Colonel Joe Boyle, Dawson City’s number one citizen. Boyle, a larger-than-life character, had made a fortune in the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898 through mining concessions and other businesses. His nickname was “King of the Klondike.”

By 1904, however, Dawson City was in decline, the gold largely played out. Its population, which had topped 40,000 at the peak of the gold rush in 1898, had fallen to less than 5,000, though there were more settlers in the surrounding hinterland. Boyle, a one-time boxing promoter with a passion for hockey, put together a four-team league consisting of miners, prospectors, police and civil servants. The small league played at a newly-built, indoor rink that amazingly boasted an attached clubhouse, dressing rooms, showers, lounges and a dining room. The Dawson City Nuggets, an “all-star” team, were drawn from this ragtag bunch. Confident of their abilities, however, somebody came up with the idea, reputedly at a “knees up” in a local saloon, of challenging the Ottawa Hockey Club’s Silver Seven for the Stanley Cup.

This wasn’t as wacky an idea as it sounds. A number of good hockey players had come to the Klondike to seek their fortunes. As one press report of the time noted, the men “continued to play hockey when they were not ‘plucking gold nuggets.’” Coincidentally, many of the players were from the Ottawa area. The team’s captain, Weldy Young, was a legitimate star who had played for the Ottawa Hockey Club during the 1890s. The team’s rover, Dr Randy McLennan, also had considerable hockey experience, having played for Queen’s University in Kingston when it challenged the Montreal AAA team in a losing cause for the Stanley Cup in 1895. However, the Ottawa team was a formidable opponent. It had defeated the Montreal Wanderers for the Stanley Cup in March 1903, and had successfully defended it against five challengers over the following year.

For reasons that are unclear, the Ottawa Club accepted the cheeky challenge from the northerners to a best of three series to be held in January 1905 in Ottawa. Col. Boyle bankrolled the Nuggets, covering their travel and other expenses of $6,000, equivalent to about $125,000 in today’s money. With the team’s likely share of the box office from the Stanley Cup games expected to be only $2,000, he also organized a series of post-Cup exhibition games in eastern Canada and the United States to help re-coup his expenses. The Dawson City Nuggets became an instant media sensation throughout North America. The Montreal Gazette called their trek out east “the most gigantic trip every undertaken by a hockey team.” Ottawa’s Evening Journal said it was “the pluckiest challenge in the history of the Stanley Cup.”

Most of the team set out from Dawson City on 19 December 1904. They were originally supposed to leave several days earlier, but their departure was delayed by a federal election in the Yukon. As it was, the team left without Weldy Young. Employed by the government, he had to work over the election period and couldn’t get the time off. He later caught up with the rest of the players, too late, however, to play in the Stanley Cup series in Ottawa. The team’s number two player, Lionel Bennett, was also a no-show. He didn’t want to leave his wife’s bedside who had been injured in a sleigh accident.

Undeterred, the team set out on the 4,300 mile (6,900 kilometre) trek to Ottawa. The first leg of their voyage was to Whitehorse, a 330-mile slog through the wilderness, on bicycle, foot, and by sled. Despite the cold and overcoming frostbite, the men made good time. They covered 46 miles on their first day alone. But it took them nine days to get to Whitehorse, sheltering at night in cabins owned by the North West Mounted Police. From Whitehorse, they caught a train to Skagway, Alaska. Delayed two days by snow storms in the White Pass, the team missed their boat and had to wait an additional three days before catching a steamer to Seattle. They then backpacked to Vancouver. At Vancouver, they boarded the transcontinental Canadian Pacific train for Ottawa. Before leaving, Boyle sent a telegram to the Ottawa Hockey Club asking for the series to be postponed to allow the Nuggets to recover from their odyssey; the request was denied.

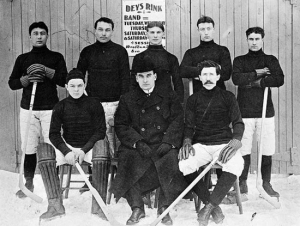

The Nuggets arrived in Ottawa on 11 January 1905, two days before their opening game at Dey’s Rink located at Gladstone and Bay Streets. The team was warmly greeted in Ottawa. The Ottawa Journal called the Dawson players “hardy Norsemen,” and opined that the “Yukon team was a sturdy lot” and would “bear themselves bravely.” The team took some light practice at the arena before the series began, as well as visited the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club to watch boxing matches and an endurance contest.

The first game of the series was held on 13 January at 8.30pm. In goal for Dawson City was 17-year old Albert Forrest, originally from Trois Rivières, Quebec. Replacing the absent Weldy Young as team captain was Dr Randy McLennan (rover). The other players included Jim Johnstone (point), Lorne Hannay (cover point), Hector Smith (centre), George Kennedy (right wing) and Norman Watt (left wing). Joe Boyle acted as the team’s manager. At the other end of the ice, Dave Finnie was in goal for Ottawa. The other Silver Seven players included Arthur “Bones” Allan (point), Art Moore (cover point), Harry “Rat” Westwick (rover), Frank McGee (centre), Alf Smith (right wing) and Fred White (left wing). Bob Shillington was the team’s general manager.

The game was played to a capacity crowd of roughly 2,500 spectators. The Governor General, Lord Grey, dropped the puck to start play. Through the first half, the Nuggets, dressed in black sweaters with gold trim, were competitive, holding the Silver Seven, wearing their red, black and white jerseys, to only three goals to their one. But the Nuggets began to flag in the second half, the effects of their trip becoming apparent. Penalties didn’t help either. A punch-up in the first half sent Norman Watt of the Nuggets and Ottawa’s Alf Smith off for ten minutes each for fighting. Tempers deteriorated further during the second half. When Art Moore, Ottawa’s cover point, tripped Watt, Watt retaliated. After he picked himself off the ice, Watt skated over to Moore and smashed him over his head with his stick, knocking him out cold for ten minutes. Two quick Ottawa goals followed. The final score was a lopsided 9-2 decision in Ottawa’s favour; Alf Smith tallied for four goals, Rat Westwick and Fred White each got two, while Frank McGee scored once. For Dawson City, Randy McLennan and George Kennedy retaliated.

Notwithstanding Watt’s brutal assault on Moore and the other fights, the Ottawa Evening Journal admired the sportsmanship displayed by both teams. In the newspaper’s description of the game, the reporter commented: “It was rather a novelty to the Ottawa public to see such a wholesome, even-tempered exhibition and it went down very well with the audience. More power to you boys!” One wonders what rough games were like during that era.

The second game of the series took place two days later on 16 January 1905. Both teams made modest changes to their line-ups. For the Nuggets, Dave Fairburn replaced Randy McLennan as rover. Harvey Pulford, the Silver Seven captain took over on point from “Bones” Allan. The national press didn’t rate the Nuggets chances very highly. The St John Daily Sun commented that the Stanley Cup would likely stay east. The newspaper commented that although the Klondikers had demonstrated they could handle the puck during the first game, the team had been “outskated, out-generalled, out-pointed in very department” by the Ottawa club. Still, the Dawson City newspaper, Yukon World, remained optimistic saying that the Klondike team had “a good chance.” The paper was wrong. Ottawa destroyed the Nuggets in the most lop-sided victory in the history of the Stanley Cup, defeating the northerners 23-2 in front of another capacity crowd at Dey’s Rink. Reports were pretty unanimous that Ottawa would have run the score up even higher if it hadn’t been for the strong goal-tending of young Albert Forrest.

Frank McGee, Ottawa’s centre, scored fourteen times, another record that still stands today. Eight of those goals were scored consecutively in less than nine minutes in the second half. McGee, an Ottawa native, was the nephew of D’Arcy McGee, the father of Confederation who was assassinated in 1868. McGee was a well-rounded athlete who had played football for the Ottawa Rough Riders during the 1890s. He had only one eye; he lost the other one in 1900 to a high stick. With a full time job as a public servant, he retired from hockey in 1906 at the tender age of 23 years. Despite his handicap, he enlisted during World War I after cheating on his vision test. He died in 1916 at the Battle of the Somme.

The evening after the blow-out, second game, the Ottawa Hockey Club hosted a party for the visiting Nuggets at the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Club, with George Murphy, president of the Ottawa Club acting as toastmaster. It must have been quite an event. The Stanley Cup, filled with champagne, was passed around the table repeatedly. Later, somebody drop-kicked the trophy onto the frozen Rideau Canal.

The team from the Klondike left Ottawa for their tour of eastern Canada and the United States. With the return of Weldy Young to the team, the Nuggets had a modicum of success, though not enough to mitigate their overwhelming defeat in Ottawa. The team then disappeared from history, though not before getting its name engraved on the Stanley Cup for all time.

In 1997 a Dawson City team took on an Ottawa Senators Alumni team in a re-enactment of the 1905 game at the Corel Centre (now the Canadian Tire Centre) in Ottawa. Retracing the steps of their predecessors, the Dawson team travelled by dog sled and snowmobile from Dawson City, to Whitehorse, to Skagway and then by ferry to Seattle, before heading to Vancouver, and finally Ottawa. Before a crowd of 6,000 the visitors were once again thumped, this time 18-0. The proceeds of the charity event, split between the two teams, went to the Ottawa Heart Institute, the Yukon Special Olympics, and Yukon Minor Hockey.

Sources:

Story suggested by André Laflamme, Ottawa Free Tours, http://www.ottawafreetour.com

Gaffin Jane, 2006. Joe Boyle: The SuperHero of the Klondike Gold Rush, http://www.diarmani.com/Articles/Gaffin/Joe%20Boyle%20--%20SuperHero%20of%20the%20Klondike%20Goldfields.htm

Gates, Michael, 2010. “The game that almost brought the Stanley Cup to Dawson,” Yukon News, 22 January.

Globe, (The), 1904. “Coming of the Gold-Diggers,” 29 November.

—————-, 1905. “Ottawa Outclassed Dawson.” 17 January.

Levett, Bruce. 1989. “2-game Series took month’s trek.” Ottawa Citizen, 27 August.

McKinley, Michael, 2000. Putting A Roof On Winter, Greystone Books: Vancouver, Toronto, New York.

Montreal Gazette (The), 1904 “The Stanley Cup Dates,” 23 November.

—————————-, 1905. “Story of the Stanley Cup,” 18 January.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1905. “Overcame All Hardships,” 13 January.

————————————, 1905. “Ottawas Victorious In the First Stanley Cup Match,” 14 January.

———————————–, 1905. “The Stanley Cup Will Not Be Going To The Klondike,” 17 January.

———————————-, 1905. “J.P. Dickson Threw Down Gauntlet To The C.A.A.U. 18 January.

Pelletier, Joe, 2014. “Great Moments in Hockey History: Stanley Cup Challenge from the Yukon,” Greatest Hockey Legends.com, 9 May.

Pittsburgh Press (The), 1905. “Hockey Flashes,” 13 January.

Rodgers, Andrew, 2011. “Dawson City Nuggets and the Ottawa Senators Alumni: Interview with Award-Winning Author Don Reddick,” TVOS, 16 March

St John Daily Sun, 1905. “Stanley Cup Will Probably Stay East,” 14 January.

Yukon World, 1904. “Dawson’s Champions And The Cup,” 18 December.

—————-, 1905. “Klondike Hockey Team Creates Great Interest In Ottawa,” 13 January.

—————, 1905. “Klondike Hockey Team Defeated In Extremely Rough Game In the Presence Of Thousands Of People,” 14 January.

—————, 1905. “Klondike Team Has Good Chance In The Game Monday Night,” 15 January.

————–, 1905, “Klondike Hockey Meet An Overwhelming Defeat At The Capital,” 17 January.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

First Royal Visit

1 September 1860

In May 1859, the Legislature of the Province of Canada invited Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert to come to British North America “to witness the progress and prosperity of this distant part of your dominions.” Specifically, the Legislature hoped that the Queen would officially open the Victoria Bridge (le pont Victoria), the first bridge to span the St Lawrence River, which joined Montreal on the north shore with St Lambert on the south shore, that was nearing completion. The visit would also “afford the opportunity the inhabitants [of the Province of Canada] of uniting in their expression of loyalty and attachment to the Throne and Empire.”

Queen Victoria regretfully declined the invitation, saying that “her duties at the seat of Empire prevent so long an absence.” Transatlantic travel in the mid nineteenth century was still an arduous journey, taking two weeks or longer, even if the weather was favourable. Instead, she offered to send her eldest son, Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales. It would be a “coming out” event for the nineteen-year old prince who would later become King Edward VII. Her suggestion was enthusiastically embraced. On hearing that the prince would be visiting British North America, U.S. President Buchanan invited him to tour the United States as well.

The extended North American tour took the young prince to all the major cities of the British colonies of North America, as well as to the major cities of the United States as far west as St Louis, Missouri. The prince’s tour naturally included Ottawa, the city selected by his mother to be the new capital of the United Province of Canada in 1857. Fortuitously, construction of the new Parliamentary buildings had commenced at the end of 1859, and the prince was invited to lay the cornerstone of the Legislature building while he was in the city.

The Prince of Wales departed England for North America on 10 July 1860 on board HMS Hero, a 91-gun, screw and sail powered ship of the line, accompanied by HMS Ariadne, a wooden, screw frigate, and was met in Newfoundland by the screw steam sloop HMB Flying Fish. On board the Hero was a true hero–William Hall. The son of a slave who had escaped to Canada during the War of 1812, Hall, was the first Canadian seaman and the first black man to receive the Victoria Cross for gallantry. He received the honour for heroism at the siege of Lucknow in 1857 during the Indian Mutiny.

The Prince and his entourage arrived in St John’s during the evening of 23 July, after having encountered heavy seas and dense fog on the crossing. Although the Newfoundland government knew roughly when the prince’s would arrive, his ship’s entrance through the Narrows caught people by surprise; ship-to-shore telegraph communications was still in the distant future. That night, the city hastily finished erecting ceremonial arches made of evergreens, and put up flags and bunting, in preparation for the prince’s official landing the next morning.

Over the following month, the prince made his way across the Atlantic colonies with considerable pomp and ceremony. After St John’s, he visited Halifax, St John, Fredericton, and Charlottetown, before the royal squadron left for the Province of Canada. It arrived in Canadian waters on 13 August where it was met by the Governor General, Sir Edmund Head, and members of the Canadian government on board two Canadian steamers in the mouth of the St Lawrence River. The flotilla reached Quebec City on 18 August. The first major event was a reception at Parliament House where he was greeted by the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly. The prince then knighted the speakers of the two houses of Parliament. He subsequently visited Trois Rivières and then Montreal, where he officially opened le pont Victoria, laying the cornerstone to the entrance to the bridge as well as setting in place a ceremonial “last rivet.” In truth, the bridge, the longest in the world at the time, had been completed the previous year, and was already open for rail traffic.

After a tour of the Eastern Townships, Prince Edward proceeded from Montreal to Ottawa on 31 August. As there was no direct train link, he travelled by way of a special train to Ste Anne-De-Bellevue, followed by boat trip to Carillion, another train ride to Grenville, where he picked up the steamer Phoenix for the last stage of his journey up the Ottawa River. He arrived in Ottawa at 7pm to be met by an armada of one hundred and fifty canoes paddled by several hundred lumbermen dressed in white trousers and red shirts with blue facing. The canoes, flying banners, escorted the steamer the last two miles to the Ottawa wharf. When the Phoenix rounded the Rockcliffe promontory, the Ottawa Field Battery fired a royal salute.

Little Ottawa, with a population of less than 15,000 people, was abuzz with excitement. Nothing like this had ever happened in the rough-and-tumble lumber town. Bunting and flags bedecked every home and office building. Ceremonial arches were built along the route to be taken by the prince and his party through the city. One such arch, spanning Spark’s Street near the Bate building, was constructed of evergreens, interspersed with heraldic shields, mottos, and 60 foot towers. It was topped by two immense urns of flowers and a huge statue of the goddess Minerva clad in armour.

In front of St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, “four chaste and elegant towers” were erected across Wellington Street “draped and festooned at their caps with cornucopias of flowers, royal standards, shields, and various other appropriate devices.” At the Ottawa end of the Union Suspension Bridge (where today’s Chaudière Bridge stands) to Hull was a massive wooden arch made of 180,000 feet of sawn lumber assembled without a single nail. The wood, worth $3,000, a huge sum in those days, was provided by the company Perley, Pattee & Brown. The suspension bridge itself was decorated with transparencies of the Queen, the Prince Consort, and the Prince of Wales which were illuminated after dusk. Similarly, Sappers’ Bridge, which connected Lower Town and Upper Town, was festooned with hundreds of Chinese lanterns. The Ottawa Citizen commented that “Ottawa appeared lovely and anxious as a bride awaiting the arrival of the bride-groom to complete her joy.”

Unfortunately, the start to the prince’s Ottawa visit was marred by a torrential rain shower just as Mayor Alexander Workman, dressed in his robes of office, commenced his dock-side welcome speech. While he soldiered on despite the soaking, the thousands of onlookers scattered for cover. After the prince thanked the mayor, he and his entourage were taken by carriage to the Victoria House Hotel at the corner of Wellington and O’Connor Streets. In their wake followed a somewhat bedraggled parade of soldiers, firemen, and government employees.

But the next day was bright and sunny for the laying of Parliament’s cornerstone. At 11am, the prince, followed by the Governor General, members of the prince’s party, Canadian Cabinet ministers dressed in blue and gold, and other dignitaries, entered the Parliamentary grounds through yet another triumphal arch; this one decorated in a Gothic style. The cornerstone ceremony was held on a dais under an elaborate canopy, surrounded by wooden bleachers to allow several thousand Ottawa citizens to view the proceedings. Following prayers offered by the chaplain to the Legislative Council, the prince approached the white Canadian marble stone. It bore the inscription This corner stone of the building intended to receive The Legislature of Canada was laid by Albert Edward, The Prince of Wales, on the first day of September MDCCCLX. The stone was suspended from a pulley above a Nepean limestone block in which there was a cavity. Into the cavity was placed a glass bottle containing a parchment scroll detailing the cornerstone ceremony and the names of the day’s participants. A collection of British and Canadian coins were also placed in the hole. The clerk of the works then supervised the laying of mortar, with the prince providing the last touch with a silver trowel engraved with a picture of the Parliament buildings. After the cornerstone was lowered into position, the prince tapped the stone three times. Following more prayers, and after officials had checked the stone with a plumb in the shape of a harp, and a level held by a lion and unicorn, the prince declared the stone to have been well and truly laid. At the end of the ceremony, Thomas Fuller and Chilion Jones of Toronto and Thomas Stent and Augustus Lever of Ottawa, the architects of the three Parliament buildings under construction, were presented to the prince. The royal party then went to view a three-dimensional model of the future library made by Charles Emil Zollikofer, a Swedish-born sculptor.

After a lunch hosted by the legislature in a wooden building on the Parliamentary grounds, the afternoon was taken up with fun and games. After the prince and his entourage had toured the city on horseback to admire the city’s decorations and the many triumphal arches erected for the occasion, they were taken to the Chaudière Falls for a singular Ottawa experience—a ride down the Government log slide used to send wood down river to avoid the falls. Two cribs of timber had been constructed to accommodate the royal party and journalists. Cheered by thousands who stood on the shore or on the many bridges over the slide, the prince shot through it to be met by hundreds of canoes mid river. While the two cribs descended without incident, the Ottawa Citizen reported that “the visages of some of the occupants of the cribs were considerable elongated on descending the first shoot.” A regatta with several canoe races followed.

The evening was marked by a very curious event—a mounted torchlight procession of “physiocarnivalogicalists” to the residence of the Prince of Wales. The members of this obscure order, who billed themselves as “the tribes of Allobrentio Forgissario,” were dressed in some sort of costume. The procession was the source of considerable amusement on the part of onlookers. On reaching the prince’s residence, the group raised a loud cheer, which the prince acknowledged through the window, before they dispersed.

After Sunday services at Christ Church (the predecessor of the current Anglican cathedral) the following morning, the prince visited Rideau Hall, the home of John McKay, the noted New Edinburgh lumber baron, and toured its magnificent grounds. Five years later, the Canadian government leased the mansion for the home of the Governor General; it purchased the home in 1868.

At 8am, Monday, 3 September, the prince and his party, escorted by the Durnham Light Infantry, left Ottawa for Brockville, the next stop on the Canadian leg of his North American tour, via Aylmer, Chats, and Armprior. He did not get back to Britain until the middle of November.

Fifty-six years to the day after the Prince of Wales had laid the cornerstone, his brother, the Duke of Connaught, re-laid it as the cornerstone of the new Parliament Building that replaced the original building, gutted in a mysterious fire in February 1916.

Sources:

Cellem, Robert, 1861. Visit Of His Royal Highness The Prince Of Wales To The British American Provinces And United States In The Year 1860, Henry Rowsell: Toronto.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1860. “Preparing To Receive The Prince! The Council & Citizens At Work!” 18 August.

———————–, 1860. “On Preparations To Receive H.R.H. The Prince of Wales,” 1 September.

————————, 1860. “The Prince in Ottawa,” 8 September.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1972. “Royal Nay hero was slave’s son,” 15 November.

Images: HMS Hero, anonymous, From Edward VII His Life and Times, published 1910.

Cornerstone Laying Ceremony, 1860, City of Ottawa Archives,

Lumbermen’s Arch, Illustrated London News.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Great Epizootic

12 October 1872

Imagine waking up one morning to discover that all motor vehicles had stopped working—no buses, no cars, no trucks, and no airplanes. People wouldn’t be able to get to work or school unless they lived close by. There would be no deliveries of food and merchandise to stores. Farmers would be left with mounds of rotting produce in the field, while factories would grind to a halt owing to a dearth of spare parts and absent workers. Meanwhile, police, firefighters and other emergency response workers would be unable to respond to urgent calls for help. Government would cease to function (okay, there might be an upside). In short, it would be a nightmare.

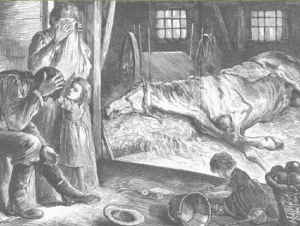

Rather than being a script worthy of a Hollywood post-apocalyptic movie, this effectively happened during the autumn of 1872, with disastrous consequences right across North America. It all started about fifteen miles north of Toronto during late September of that year. Horses in the townships of York, Scarborough and Markham began to sicken, coming down with a sore throat, a slight swelling of the glands, a severe hacking cough, a brownish-yellow discharge from the nose, a loss of appetite and general feebleness. Veterinaries hadn’t seen anything like it before. On 30 September, Andrew Smith, veterinary surgeon of the Ontario Veterinary College in Toronto, found fourteen stricken horses in one stable. Three days later, three-quarters of the horses in the district were infected.

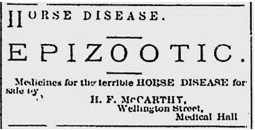

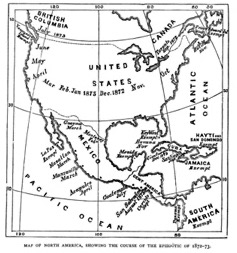

The disease quickly spread to Toronto and beyond. It was reported in Ottawa on 12 October, and within a month had reached the east coast. Only Prince Edward Island, cut off from the mainland, escaped the disease. Horses in the United States also began to sicken, the disease striking Buffalo and Detroit by 13 October, and spreading within days to all the major cities on the eastern seaboard. The illness was identified in Chicago on 29 October after a number of horses imported from Toronto a few days earlier fell ill. By mid-March 1873, the disease had reached all the way to California, in the process disrupting a war between the U.S. cavalry and Apache warriors underway in Arizona Territory. With their horses incapacitated, cavalrymen and warriors fought on foot. A year after the Toronto-area outbreak, the illness had spread south to Nicaragua in Central America. The epidemic became known as the “Great Epizootic,” since it was an epidemic than infected animals, or “Canadian horse distemper.”

The horses were ill with equine influenza which we now know is caused by two types of related viruses, equine 1 (H7N7) and equine 2 (H3N8). But at the time, it was widely believed that the disease was due to something in the air. The Ottawa Daily Citizen reported that it was the opinion of a well-known veterinary surgeon that the disease was caused by atmospheric influences, “probably having some connection with [] recent thunderstorms.” The disease was typically not fatal, having a mortality rate of 1-3 per cent though it reached 10 per cent in some areas. However, the morbidity rate approached 100 per cent. Horses were left incapacitated for up to a month, hobbling transportation across the continent.

Within ten days of its first appearance in Ottawa, the situation had become serious in the capital, with the disease having “assumed a violent form as to cause considerable anxiety to horse owners.” All public livery stables were affected, as were an increasing number of stables owned by private citizens. By 21 October, veterinaries were dealing with hundreds of cases each day. It was estimated that fewer than 50 horses in the Ottawa region were unaffected. The horse-drawn street railway service that provided public transit from New Edinburgh through downtown to LeBreton Flats was temporarily suspended when all but six of its horses came down with influenza. One died.

Within ten days of its first appearance in Ottawa, the situation had become serious in the capital, with the disease having “assumed a violent form as to cause considerable anxiety to horse owners.” All public livery stables were affected, as were an increasing number of stables owned by private citizens. By 21 October, veterinaries were dealing with hundreds of cases each day. It was estimated that fewer than 50 horses in the Ottawa region were unaffected. The horse-drawn street railway service that provided public transit from New Edinburgh through downtown to LeBreton Flats was temporarily suspended when all but six of its horses came down with influenza. One died.

The Ottawa Daily Citizen recommended that infected horses should be kept warm in well-ventilated stables and fed soft food, such as oatmeal, boiled oats, or gruel. To promote an appetite, the newspaper suggested that owners try to temp sick horses with a carrot or apple. It also recommended cleaning out stables with bromo-chloralum, a deodorant and disinfectant. According for an advertisement for the product, it protected against “atmospheric influences which contribute to the spreading of disease.”

Small-town Ottawa got off lightly. Big U.S. cities like New York City and Boston, where horses were crammed together in dirty, multi-storied, urban stables, fared far worse. In New York City, more than 30,000 horses sickened within the course of a few days. At least 1,400 animals died of the disease. City transit failed, a major inconvenience for people living in the suburbs. Businesses and draymen, who transported goods on flat-bed wagons, were reported to be the worst affected. In Boston, oxen were brought in to replace sick horses on some transit lines. Tragically, on 9 November 1872, a fire started in a hoop-skirt factory in downtown Boston. In normal circumstances, it would have been easily contained. However, with all its horses down with the flu, the fire service was unable to respond in time, and the fire quickly got out of control. More than 775 buildings housing in excess of 1,000 businesses were destroyed. As many as twenty people perished.

Epizootic Map of North America showing the spread of epizootic

Epizootic Map of North America showing the spread of epizootic

A. Judson, 1873. "History and Course of the Epizootic Among Horses Upon the North American Continent, 1872-73"The economic consequences of the disease as it spread across the continent were immense. In addition to cities coming to a virtual standstill for close to a month, traffic on the important Erie Canal from New York to Buffalo came to a halt as the horses that pulled the barges sickened. Even railways were affected as they ran out of coal that was shipped to rail terminals by horse-drawn wagons. Things got so bad that the United States was forced to import healthy horses from Mexico. Many economists believe that the Great Epizootic set the stage for the “Panic” of 1873, an economic depression that lasted for six years. The disease underscored the fragility of an animal-dependent economy.

The epidemic was the first disease whose advance was closely tracked across a continent. In the process, it became abundantly clear that “atmospheric conditions” had nothing to do with the contagion. A study of the disease debunked the idea that “cold, heat, humidity, season, climate, or altitude” or any other “unrecognized atmospheric conditions” had any bearing on the disease. Rather, the disease was spread “by virtue of its communicability.” Everywhere the disease struck was in contact with other places by means of horses or mules. Supporting this conclusion was the fact that isolated places, such as Prince Edward Island in the east or Vancouver Island in the west, were spared the disease; PEI was cut off due to bad winter weather, while a quarantine against the importation of horses was established on Vancouver Island. This analysis helped overturn the “miasma” theory of disease, which attributed illnesses to poisonous vapours, in favour of the “germ theory” of disease. It also set the stage for a better understanding of how disease is transmitted among humans, something that would become of vital importance less than fifty years later with the spread of the Spanish flu, a similar human disease that conservatively killed fifty million people at the end of World War I.

Sources:

Churcher, C. 2014, “Local Railway Items from Ottawa newspapers—1872,” The Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1872. “Ottawa City Passenger,” 19 October.

——————–, 2014, “Local Railway Items from Ottawa newspapers—1872,” The Ottawa Free Press, 1872, “Ottawa City Passenger,” 23 October.

Facts on File, 2014. Great Epizootic, Entry 602.

Judson, Adoniram, B. M.D., 1873. “History and Course of the Epizootic Among Horses Upon The North American Continent, 1872-73,” American Public Health Association, Public Health, Reports and Papers, 1873.

Heritage Restorations, H2012. “The Great Epizootic of 1872,” SustainLife Quarterly Journal, (Fall), Ploughshares Institute for Sustainable Culture.

Horsetalk, 2014. “How Equine Flu brought the US to a standstill,” 17 February.

Murnane, Brigadier Dr. Thomas, 2014. James Law, America’s First Veterinary Epidemiologist and The Equine Influenza Epizootic of 1872, The Long Riders Guild Academic Foundation.

Passing Strangeness, 2009. The Great Epizootic, 13 May,.

The Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1872. “Epizootic,” 21 October.

The Public Ledger, 1872. “The Epizootic in the United States,” 16 November.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Canada’s Birthday 1 July 1867

1 July 1867

Each 1 July, Canadians across the country celebrate Canada’s birthday with cultural events and fireworks. The anniversary, which officially became Canada Day in 1982, was originally known as Dominion Day. Nowhere is the national holiday more sumptuously celebrated than in Ottawa, the nation’s capital. On the greensward in front of the Parliament buildings, thousands of patriotic Canadians flock to see the “Changing of the Guard,” performed by the Governor General’s Foot Guards dressed in their traditional scarlet tunics and bearskin hats. Canadian performing artists entertain the crowds through the day on a large stage specially erected for the occasion. After dusk, Parliament Hill is lit up with a dazzling display of fireworks.

Given this annual burst of patriotic fervour, it may come as a surprise that many Canadians don’t fully understand the event they are celebrating. Even officialdom gets it wrong. The Official Website of Ottawa Tourism, describes Canada Day as “the anniversary of Confederation, when Canada became a country separate from the British Empire.” Yes, 1 July is indeed the anniversary of Confederation. But no, Canada did not become separate from the British Empire on that date. Canadian legislative autonomy did not come until the Statute of Westminster in 1931, when the imperial government in London gave up its right to legislate for Canada and other Dominions. Even then, Canadians remained British subjects, and regarded themselves as members of the British Empire. Canadian legal decisions could also still be appealed to the Judicial Committee of the House of Lords in London, and Canadian constitutional changes required the consent of the British Parliament.

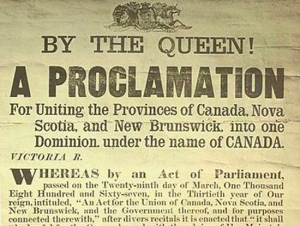

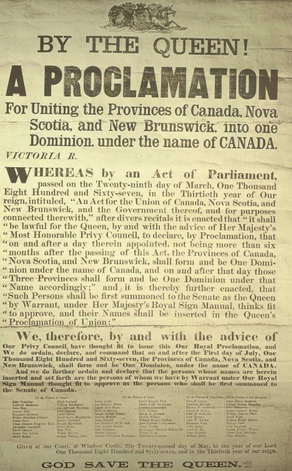

Instead of representing the birth of a new independent country, Canada Day marks the anniversary of the union of three pre-existing British colonies in North America—the Province of Canada, which itself was the result of the fusion of Upper and Lower Canada in 1841, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. The new entity was called the Dominion of Canada, hence, the original name for the holiday. The proclamation of the new Dominion by Queen Victoria on 1 July 1867 was the culmination of years of negotiations to unite the colonies of British North America. Motivated by a range of economic and political factors, including fears of annexation by their U.S. neighbour to the south, the “fathers of Confederation” had met in 1864, first in Charlottetown and later in Quebec City, to thrash out the details of forming a federation. After working out most provisions dealing with the country’s organization and the distribution of powers between the federal and provincial governments, a small group of nation-builders met in London, England in December 1866 to put the final touches on draft legislation to be submitted to the British Parliament. John. A. Macdonald had wanted the official name of the new federation to be the “Kingdom of Canada.” But at the eleventh hour, the British government, concerned about offending the republican government to the south, suggested “Dominion” as a less provocative style.

The British North America Act was first submitted to the House of Lords on 19 February 1867. There, the colonial secretary, Lord Carnarvon, opened the proceedings by saying: “We are laying the foundations of a great State, perhaps one that at a future date may even overshadow this country.” A week later, the bill was introduced into the House of Commons. The bill passed through the British Parliament without change, and was given Royal Assent on 29 March 1867, to take effect on 1 July.

The Act, which became Canada’s constitution, delineated the respective powers of the federal and provincial governments, and guaranteed minority rights, including linguistic rights. The Province of Canada was also split into its two component parts, allowing Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec) to separately govern their own local affairs instead of together—a source of considerable strife during the previous twenty-five year existence of the Province of Canada. Some saw Confederation as a bulwark against U.S.-style democracy where majority rule could trump minority rights. The Ottawa Times declared that “The first of July, A.D., 1867, will ever be a memorable day in the history of this continent. It will mark a very solemn era in the progress of British America. By the Constitution which this day comes in force will be solved the great problem—a problem in which not we alone, but the whole world is intimately concerned—whether British constitutional principles are to take root and flourish on the Western Hemisphere, or unbridled Democracy shall have a whole continent on which to erect the despotism of the mob.”

The constitutional arrangement between the new Dominion and Great Britain remained unchanged from that which had existed prior to Confederation between the colonies in British North America and the mother country. Like the colonial governments that had preceded it, the new Dominion government was responsible for domestic affairs, while the imperial government in London retained responsibility for foreign affairs. The imperial government (or more correctly the Crown on the advice of the imperial government) also continued to appoint the governor general as it had done previously for each of the colonies, and retained its right to override Canadian legislation. Consequently, when the new Dominion was born on 1 July 1867, it remained an integral part of the British Empire, its government subordinate to the imperial government in London.

The birth of the new Dominion of Canada was greeted with great enthusiasm in Ottawa. Selected by Queen Victoria in 1857 as the capital of the Province of Canada, it was now the capital of a far larger political entity; few had doubts that the remaining British colonies in North American would join the new Dominion, building a country that spanned the continent. This took some time, however; Newfoundland and Labrador, the last to join, didn’t sign up until 1949.

In Ottawa, the partying started the night before the big day as people made their way to Major’s Hill to welcome in the new Dominion at midnight. At the stroke of twelve of the Notre Dame Cathedral clock, a huge pyramidal bonfire made of firewood and tar barrels, surrounded by a ring of boulders to protect spectators, was set ablaze. Thousands of Ottawa citizens, including the Mayor and members of the city council, gave “three hearty cheers,” for the Queen, and three more for the new Dominion of Canada. Churches throughout the city rang their bells, while the Ottawa Field Battery at the drill shed in Lower Town gave a 101-gun salute to the new country. Rockets and Roman candles lit the sky. Paul Favreau and his band played music to the crowd until dawn.

Proclamation announcing the formation of one Dominion, under the name of CANADA, 1867With the arrival of daylight on Monday 1 July 1867, the city “never looked better” to greet the thousands of visitors that were streaming into the capital from the countryside to join in the festivities. Bunting, flags, and streamers decorated public and private buildings alike along Sparks, Rideau and Sussex streets. At 7am, a lacrosse tournament between the Huron and Union Clubs commenced on Ashburnham Hill, the area east of today’s Bronson Avenue, between Lisgar Street and Laurier Avenue. At 10am, an honour guard from the Rifle Brigade took up position in front of the East Block on Parliament Hill to await the arrival of Lord Monck, the newly designated governor general of the Dominion of Canada. A half hour later, a salute from the Field Battery announced Monck’s appearance who was received by guards with presented arms. At 11am, the Queen’s proclamation was read out by Ottawa’s mayor. Dignitaries then entered the Executive Council Chamber. Monck, in plain clothes, advanced to the head of the Council table, read the Royal Instructions making him Governor General, and was sworn in by Canada’s Chief Justice. After the various oaths, the Field Battery on Major Hill’s gave another salute. The Governor General then conferred the title of Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath on John A. Macdonald for his contribution to making Confederation a reality. Several others received knighthoods of lesser orders. George-Étienne Cartier, Macdonald’s partner, was also offered a knighthood, but he refused it on the grounds it was inferior to that awarded to Macdonald. The following year, Cartier was made a baronet, a more illustrious honour, which also carried the title “Sir.”

Proclamation announcing the formation of one Dominion, under the name of CANADA, 1867With the arrival of daylight on Monday 1 July 1867, the city “never looked better” to greet the thousands of visitors that were streaming into the capital from the countryside to join in the festivities. Bunting, flags, and streamers decorated public and private buildings alike along Sparks, Rideau and Sussex streets. At 7am, a lacrosse tournament between the Huron and Union Clubs commenced on Ashburnham Hill, the area east of today’s Bronson Avenue, between Lisgar Street and Laurier Avenue. At 10am, an honour guard from the Rifle Brigade took up position in front of the East Block on Parliament Hill to await the arrival of Lord Monck, the newly designated governor general of the Dominion of Canada. A half hour later, a salute from the Field Battery announced Monck’s appearance who was received by guards with presented arms. At 11am, the Queen’s proclamation was read out by Ottawa’s mayor. Dignitaries then entered the Executive Council Chamber. Monck, in plain clothes, advanced to the head of the Council table, read the Royal Instructions making him Governor General, and was sworn in by Canada’s Chief Justice. After the various oaths, the Field Battery on Major Hill’s gave another salute. The Governor General then conferred the title of Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath on John A. Macdonald for his contribution to making Confederation a reality. Several others received knighthoods of lesser orders. George-Étienne Cartier, Macdonald’s partner, was also offered a knighthood, but he refused it on the grounds it was inferior to that awarded to Macdonald. The following year, Cartier was made a baronet, a more illustrious honour, which also carried the title “Sir.”

At noon, a massed military display was held on Parliament Hill, consisting of the Rifle Brigade, the Civil Service Rifles, the Carleton 43rd Infantry, the Ottawa Provisional Battalion of Rifles, the Ottawa Provisional Brigade of the Garrison Artillery, and the Ottawa and Victoria Cadet Corps. The show was slightly marred when the Civil Service Rifles fired a “feu de joie,” a sort of grande finale. Unfortunately, the order to “Fire” was not preceeded by the command “Remove ramrods.” A volley of ramrods was launched from Parliament Hill, across Wellington Street, to land in a hail of sparks on Sparks Street.

The military display was followed by athletic games on Major Hill. Games included the “standing” and “running” leaps, the 100-yard dash, as well as boat and canoe races. Across the city, a lunch was provided to the Carleton Infantry by Alderman Rochester at his own expense. The previous night, he had heard that the men would be arriving from the country for the parade and festivities without any refreshment organized for them. The alderman hosted the men and their families outdoors at his home, determined to rescue the “fair name of the city from the charge of want of hospitality.” More sporting events were held in New Edinburgh, including some unusual ones—a three legged race, a blindfold race, and a cricket ball throwing contest.

In the evening, another bonfire was lit, this time at Ashburnham Hill. Twenty-two cords of wood were sent up in flames. After dusk, fireworks were launched at Parliament Hill. Across the water in Hull, people picnicked as they watched the display. Music and dancing continued to the wee hours of the morning before Ottawa’s populace returned home exhausted, citizens of a new Dominion.

Sources:

Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 2014. “Cartier, Sir George-Étienne, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cartier_george_etienne_10E.html.

Foster, Robert, Capt.et al, 1999. Steady the Buttons, Two by Two, Regimental History of the Governor General’s Foot Guards, Ottawa.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The End of the Crippler

18 April 1955

Anti-Polio Advertisement,

Anti-Polio Advertisement,

The Ottawa Journal, 2 February 1950

Thanks to vaccines we no longer live in fear of many infectious diseases that used to stalk the world killing millions each year, and maiming or crippling tens of millions more. By the early 1950s, Canadian children were routinely immunized against smallpox, diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus. But several diseases remained to be conquered. One of the most feared was poliomyelitis, also known as infantile paralysis for its propensity to affect the young, or “the Crippler.”

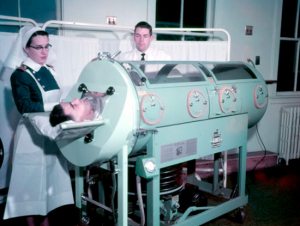

The disease is caused by the poliovirus, a type of enterovirus of the family Picornaviridae. It was first isolated in 1908 by the Austrian researchers and physicians Karl Landsteiner and Erwin Popper. The virus has three serotype versions (PV1-Brunhide, PV2-Lansing and PV3-Leon). All are virulent, though PV1-Brunhide is the most common strain, and the one most associated with paralysis. Most people who come into contact with the polio virus experience no symptoms beyond a sore throat, a gastrointestinal upset, a slight fever, and a general malaise. Called “abortive polio,” this is considered a minor illness that leaves no permanent effects. A small percentage of victims experience “aseptic” polio that also involves severe neck, back and muscle pain, as well as a bad fever. In a still smaller percentage of sufferers, the polio virus attacks the central nervous system leading to muscle flaccidity, especially of the limbs, and paralysis. Depending on what part of the nervous system is affected, “paralytic” polio is classified as spinal, bulbar, and bulbospinal. In some cases, the diaphragm and chest muscles are affected. Sufferers of this form of the disease need help to breath. In 1927, two Harvard researchers invented the “iron lung,” into which paralysed patients were placed to aid their breathing mechanically. Although most were able to leave the machine after several weeks, some were confined for years, or had to use a portable breathing apparatus. Polio suffers whose limbs had become paralyzed sometimes recovered their use after a few weeks. However, some many were left permanently disabled. Two to ten per cent of people stricken with paralytic polio died. There is no cure for the disease, only prevention.

Although polio has been around for thousands of years, it didn’t use to have the fearful reputation that it had during the first half of the twentieth century. For the most part, people had acquired a natural immunity to the disease. But as living standards and hygiene improved, the incidence of the disease paradoxically increased. The natural immunity that protected people had been weakened or lost. According to Christopher Rutty, a medical historian, fears about polio, heightened by publicity, were disproportionate to the risk of catching the paralytic form of the disease. But frightened parents told their children to “regard [polio] as a fierce monster” that was “more sinister than death itself.” The fact that people at the time didn’t understand the transmission mechanism of the disease (typically faecal-oral) made it all the scarier. You didn’t know what to do to protect yourself and your family. When outbreaks occurred, often during the summer months, health officials in epidemic areas closed cinemas, playgrounds, and delayed school openings. In Ottawa, when the federal government announced in 1950 that the water from the Rideau River would be temporarily diverted to allow for repairs near its outfall into the Ottawa River, residents of Sandy Hill, fearful of polio-infected flies that might breed in exposed marshes and refuse, lobbied for the repairs to be delayed until after the summer polio season.

People stricken with polio were sent to special isolation hospitals for a minimum of seven days required by provincial law. Their families were quarantined. Ottawa’s Strathcona Isolation Hospital was one of six designated centres for the treatment of polio in Ontario. The other centres were located in Toronto, Kingston, London, Hamilton and Windsor. The Strathcona Hospital’s “territory” ran from Pembroke to Morrisburg. In 1953, the old hospital was closed when a new East Lawn Pavilion with isolation facilities was opened at the Ottawa Civic Hospital. Seventeen patients were transferred from the Strathcona facility, including one in an iron lung. Although this was a time before provincial health insurance (OHIP), the care for polio victims was paid for by the provincial government. Later, following complaints by doctors that they couldn’t submit bills to well-to-to polio patients, the government modified the rules to allow doctors to charge wealthy patients. Poor patients continued to receive free care at teaching hospitals connected to universities.

Advertisement for the Canadian March of Dimes, 1950 Campaign

Advertisement for the Canadian March of Dimes, 1950 Campaign

The Ottawa Journal, 4 February 1950Following the election of Franklin Roosevelt at President of the United States in 1933, who was himself a polio survivor, the medical profession in the United States and Canada took aim at the disease. Funding for research into the development of a vaccine was provided in the United States by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis that had its roots in a private anti-polio organization started by the Roosevelt family. The Foundation sponsored an annual March of Dimes campaign supported by Hollywood stars to raise money to find a cure for the disease and to care for polio victims. In Canada, a parallel organization called the Canadian Foundation for Poliomyelitis was founded in Ottawa in 1949. The Canadian Foundation held the first Canadian March of Dimes campaign the following year. Newspapers across the country carried the photograph of “Linda,” a child polio victim wearing iron leg braces. In Ottawa, twenty-five hundred blue and red checkered collection boxes were distributed in stores, banks and restaurants.

In 1953, North America experienced it worst outbreak of polio in decades. In Canada, there were 8,878 reported cases, mostly in Manitoba and Ontario, with a death rate of 3.3 persons per 100,000 population, far higher than during earlier outbreaks. Ottawa had 100 recorded cases by the end of that year’s polio season with four deaths. To help control the spread of the disease, Dr J. J. Dey, the city’s medical officer of health, advised Ottawa citizens not to drink unpasteurized milk, not to jump into water when the body was tired, and to avoid fatigue. He also told people to stay away from crowds, to keep the house free from flies, and to wash all fruits and vegetables. More usefully, he advised people to wash their hands frequently, and to boil drinking water if one had any doubts.

Fortunately, by this time, a vaccine was close at hand. In 1949, Harvard scientist Dr John Enders discovered that the polio virus could be propagated in the organs of monkeys. The following year, the Polish-born virologist Hilary Koprowski developed an experimental oral vaccine using a live but weakened virus of the PV2-Lansing variety of the disease, and successfully immunized some twenty children in New York State.

Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh, 1955

Jonas Salk at the University of Pittsburgh, 1955

The Owl - University of Pittsburgh Digital Archives, WikipediaMeanwhile, at the University of Pittsburgh, Jonas Salk was working on determining the number of different strains of polioviruses and developing a vaccine using dead viruses that would be effective against all strains of the disease. Connaught Laboratories at the University of Toronto, supported by a federal grant as well as money provided by the Canadian March of Dimes, was also developing the procedure for producing industrial-size quantities of the polio virus, a necessary and vital step for the mass production of the Salk vaccine. Related work was conducted at the Institute of Microbiology and Hygiene in Montreal. Connaught later supplied much of the virus that went into making the Salk vaccine in North America as well as making the vaccine itself for the Canadian inoculation campaign.

By 1954, Salk who had safely tested his vaccine first on his family and then on 700 volunteers was ready for a large-scale test. He organized a trial involving two million children. Half received a three-shot dose of the experimental vaccine over a period of several weeks with the other half receiving placebos. Most of the children were American. But U.S. authorities offered 50,000 doses to Canada. Health departments in Alberta and Nova Scotia took up the offer and inoculated thousands of young children. In mid-April 1955, the results of the trial were announced to a packed conference room at the University of Michigan: polio had been defeated! The vaccine had been 80% effective in protecting children from the disease. The relief was palpable. Immediately, steps were taken to inoculate all children in North America starting with those in Grades 1 and 2.

Polio shots at Elgin Street Public School, 1955

Polio shots at Elgin Street Public School, 1955

Newton Photographic Associates Ltd., City of Ottawa Archives, MG393-NP-36093-006, CA-025699In Canada, the inoculations were paid for on a 50:50 basis by the federal and provincial governments. Youngsters in Toronto and Pembroke received the first dose of the vaccine in early April even before the official announcement of Salk’s successful mass trial. The inoculation programme began in Ottawa on Monday, 18 April 1955. That morning, Grade 1 and 2 students at four public schools (Elgin, Lady Evelyn, Borden and Cambridge) and five separate schools (Ste Famille, St Patrick, St Jean Baptiste, St Anthony and Christ the King) received their first round of shots. That afternoon, five more schools were visited by teams of nurses. Children in remaining schools received their shots through the week. Parents had to sign a consent form for their children to receive the inoculation with the warning that if the children missed the first shot, they couldn’t receive the subsequent shots. Across the Ottawa River in Hull, the inoculation programme started in May with children aged two to three years since that age group had been most affected in Quebec during the 1953 epidemic.

In the midst of the roll-out of the continent-wide vaccination campaign, disaster struck. Some children in the United States came down with polio after having received their shots. Several died. The problem was traced to poor quality control at the Cutter Laboratories of Berkeley, California, one of six American vaccine manufacturers. Their vaccine contained live instead of dead viruses. According to the Journal of Pediatrics, the vaccine had been rushed. The U.S. vaccination programme was temporarily suspended despite the coming onset of the 1955 polio season. In Canada, Health Minister Paul Martin Sr faced one of the toughest decisions of his life: should the Canadian programme also be suspended as Prime Minister St Laurent wished? With all of the Canadian vaccine produced at Toronto’s Connaught Laboratories, and having full confidence in Canadian scientists and doctors, he ordered the Canadian programme to go ahead as planned. No Canadian child came down with polio as result of the vaccine.

By August 1955, the number of polio cases in Canada and the United States had dropped dramatically even though only a portion of children had been immunized. In November, Paul Martin publicly stated “I don’t think there can be any doubt that it [the vaccine] has had some effect.” By 1962, the number of reported polio cases in Canada had fallen to only 89.

In the early 1960s, the Salk vaccine was generally replaced by an oral vaccine using live but weakened viruses developed by Albert Sabin who drew on the earlier work of Hilary Koprowski. The Sabin vaccine was cheap to produce and administer and was very powerful—95 per cent effective after three doses (one for each polio strain). Polio infection rates around the world plummeted. In 1988, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a campaign to eradicated polio from the world supported by national governments, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF, Rotary International and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. In 2000, the Americas were certified as polio free. In 2014, South-East Asia was certified as polio free. By 2016, the number of reported polio cases worldwide had dropped to only 37 located in Nigeria, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The WHO estimates that because of the global vaccination campaign, 16 million people walk today who otherwise would have been paralyzed. Many, many lives have also been saved. However, war and civil strife threaten this achievement. Endemic transmission of the disease continues in the three remaining polio hotspots. With vaccination efforts disrupted in these areas, the Crippler could well return.

Sources:

CBC Archives, 1993. A History of Polio in Canada, posted 7 April 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014, Poliomyelitis.

Council Bluffs Nonpareil (Iowa), 1954. “Report Results of Polio Research,” 11 April.

MedicineNet.com. 2017. Medical Definition of Abortive Polio.

Museum of Health Care at Kingston, 2017, Polio.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1949. “First Fatal Polio Case,” 20 July.

————————–, 1949. “Ottawa Cases of Polio Total 29 This Year,” 15 August.

————————–, 1949. “Foundation Plans Drive For Funds to Fight Polio,” 4 November.

————————–, 1950. “Rideau Draining To Proceed,” 10 August.

————————–, 1950. “St. Germain’s Protest Against Rideau Draining,” 15 August.

————————–, 1950. “March of Dimes For Polio Victims Starts Sunday,” 30 December.

————————–, 1953. “Ontario Announces new Policy For Treating Polio,”6 January.

————————–, 1953. “MOH Issues Statement on Polio,” 17 July.

————————–, 1953. “Lab Producing Polio Virus In Quantities,” 25 September.

————————–, 1953. “Polio Season Is Over,” 14 October.

————————–, 1953. “Hope-Filled Polio Vaccine For Million U.S. Children,” 17 November.

————————–, 1953. “New East Lawn Pavilion Opened At Civic,” 16 December

————————–, 1954. “Provinces Offered U.S. Polio Vaccine,”26 May.

————————–, 1955. “Polio Shots April 18 For Ottawa Children,” 4 March.

————————–, 1955. “Ottawa Will Start Trials of Polio Vaccine April 18,” 9 April.

————————–, 1955. “SALK CONQUERS POLIO,” 12 April.

————————–, 1955. “Salk Was So Confident of Success His Own Children Got Vaccine First,” 12 April.

————————–, 1955. “Ontario to Provide Injections for All School Children,” 12 April.

————————–, 1955. “Man’s Victory Over Polio,” 13 April.

————————–, 1955. “Duplessis Decides Quebec To Take Part In Anti-Polio Plan,” 15 April.

————————-, 1955. “First Week of Vaccine Shots Against Polio Start Monday,” 16 April.

————————–, 1955. “Salk Answers Critical Questions,” 7 June.

————————–, 1955. “Vaccine Producer Sued After boy Contracts Polio,” 24 June.

————————–, 1955. “U.S.A. ‘Polio Vaccine Mixup,’” 27 July.

————————–, 1955. “Big Drop In Deaths By Polio,” 12 August.

————————–, 1955. “U.S. Polio Fatalities Reduced Sharply,” 12 August.

————————–, 1955. “Martin Credits Salk Vaccine,” 1 November.

Rutty, Christopher, 1995. “Do Something!…Anything! Poliomyelitis in Canada, 1927-1962”.

———————-, 1999. The Middle-Class Plague: Epidemic Polio and the Canadian State, 1936-37.

Smithsonian, National Museum of American History, 2017. The Iron Lung and Other Equipment.