James Powell

British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

17 December 1939

“You must get on with the war, and in order to enable you to do so I now declare No.2 Service Flying Training School [SFTS] open,” said the Governor General, the Earl of Athlone, under bright blue skies at Uplands Airport just outside of Ottawa. With these words, the first intermediate flying school of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) was open for business. (No. 1 SFTS, located at Camp Borden opened three months later.) Eight Elementary Flying Training Schools (EFTS), located across the country, had already opened earlier that summer to provide basic flying skills to novice flyers.

The opening of No.2 SFTS came none too soon. Across the Atlantic that afternoon of 5 August 1940, the Battle of Britain was raging. With the RAF sorely stretched, trained pilots were desperately needed, both for the battle underway and for the successful future prosecution of the air war against the German Luftwaffe.

The genesis of the BCATP dated back to the mid-1930s when Britain, conscious of the growing Nazi threat, began to rebuild its armed forces, including its air service. In 1936, a Scottish-Canadian in the Royal Air Force (RAF), Group Captain Robert Leckie, wrote a memorandum to Arthur Tedder, then Director of Training at the British Air Ministry, suggesting Canada as an ideal location to train air crews. Canada was safe from enemy attack, and was close to the U.S. industrial heartland which could supply necessary aircraft engines and parts.

Additionally, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) had a close relationship with its British counterpart. As well, the RAF routinely recruited Canadians for both short-term and permanent positions. Moreover, during the latter years of World War I, flight training schools had been established in Canada by the Royal Flying Corps, the forerunner of the RAF.

When Prime Minister Mackenzie King got wind of the idea, he was conflicted. On the one hand, he was very protective of Canada’s new sovereignty. Following the ratification of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, Canada was no longer subordinate to Great Britain either domestically or internationally. Consequently, he could not support RAF bases in Canada. The Prime Minister was also conscious of how the presence of British bases in Canada might appear to Quebec voters. On the other hand, he thought that if Canada’s contribution to the coming war effort could be largely focused on training air crews in Canada, it might be possible to avoid both large-scale casualties and a repeat of the conscription crisis that had divided the country during the previous war.

Agreement was reached to increase the number of Canadian-trained pilots for the RAF, and steps were taken to develop a common RAF/RCAF flying syllabus among other things. However, Leckie’s concept of using Canada for RAF training bases was put on the backburner until the outbreak of war in September 1939 when Vincent Massey, Canada’s High Commissioner in London, met with his Australian counterpart, Stanley Bruce. Out of this meeting was born the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Who came up with idea is unclear as both men took credit for it. Regardless, they made a joint submission to the British authorities. Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, was enthusiastic, and made a personal appeal to Mackenzie King asking him to give the proposal his very urgent attention. Chamberlain expressed the view that the establishment of training bases in Canada safe from German attack would have a psychological impact on Germany equivalent to that produced by the entry of the United States into the previous war.

While Prime Minister King was initially upset that Massey had exceeded his authority, he quickly warmed to the idea…with conditions. Most importantly, Canadian sovereignty had to be respected. The flying schools would come under the authority of the Canadian government and would be administered by the RCAF. Consequently, trainees would be attached to the RCAF, would be subject to its jurisdiction, and would receive Canadian rates of pay. King also demanded that Britain agree to purchase Canadian wheat and that the BCATP would take priority over other Canadian war commitments. He also wanted Canadian pilots to be sent after graduation to RCAF squadrons in Britain as opposed to being subsumed into the RAF.

The Australians and Zealanders also had conditions of their own, importantly that costs be shared on the basis of population and that elementary flying instruction for their pilots would be conducted at home.

With these terms acceptable to the British, King sent his agreement in principle to Chamberlain at the end of September 1939 though his government continued to worry about the scale and cost of the venture.

Over the next three months, Canadian, British, Australian and New Zealand negotiators thrashed out the fine print of the accord and how the costs would be divided. It was hard going at times. But in the wee hours of 17 December 1939, Mackenzie King’s birthday, the Canadian prime minister signed the accord, followed by Lord Riverdale on behalf of the British government. As the Australian and New Zealander delegates had already left Ottawa, their governments’ signatures were appended later.

The agreement was officially titled “An Agreement to the Training of Pilots and Aircraft Crews in Canada and their Subsequent Service.” Later that day, in a radio address to the nation, King described the agreement as “a co-operative undertaking of great magnitude.” Charles Power, the Minister of National Defence, called it “the most grandiose single enterprise which Canada has ever embarked.” In a similar broadcast, Chamberlain, as requested by King, said that the BCATP would be more effective than any other kind of Canadian military co-operation. However, he added that the British Government would welcome “no less heartily” Canadian land forces in the theatre of conflict as soon as possible.

The cost of the agreement, which was to run until end-March 1943 unless otherwise extended, was placed at $607 million of which Canada’s share would be $353 million. The British contribution was set at $185 million, mainly in the form of airplanes and parts. The Australians and New Zealanders would contribute $40.2 million and $28.8 million, respectively.

Work immediately began to make the agreement a reality, with C.D. Howe, the Minister of Munitions and Supply, taking charge. Within days, offices were organized in temporary buildings in Ottawa, and contracts signed. By early spring 1940, air fields were being prepared, and the construction of hangers and other facilities underway.

Here in Ottawa, No. 2 SFTS, making use of an existing civilian airfield, practically sprang out of the ground overnight. In the space of just a few months, roughly forty buildings were constructed at the edge of Uplands field on what the Citizen described as a “desert waste of hillocks, tufted here and there with rank, saffron-coloured grass.”

The flying school boasted five double hangars to store aircraft, each 224 feet by 160 feet with 20-foot sliding doors. There were also buildings to house ambulances, a fire truck, refueling tankers, tractors, and other vehicles. There were quarters for 1,100 military and civilian personnel with canteens, messes, a recreation building, and a sports pavilion. As well, there were a supply depot, a guard house, a watch office, a drill hall, a ground instruction school, two bombing instruction schools, and a 34-bed hospital. Special storage tanks held 20,000 gallons of aviation fuel. There was also a depot for aerial bombs and machine gun ammunition. Located close to the main runway was an air-traffic control room. The landing facilities consisted of three tarmacked landing strips and three grass strips. Planes could land in every direction. There were also two subsidiary air fields located at Edwards and Pendleton, Ontario.

As the Ottawa training school was for intermediate training, pilots assigned to No.2 SFTS had already received flight instruction on Fleet or Tiger Moth aircraft, accumulating 40-50 hours of solo training. The maximum speed of these airplanes was 90-100 miles per hour. In Ottawa, the men graduated to Harvard training craft, capable of a top speed of more than 200 mph.

The Harvards, which were painted bright yellow, were dual-controlled, and were powered by 400hp Pratt & Whitney engines. The twelve planes stationed initially at Ottawa were built by the North American Aviation Company of California. More were in transit. Later, Harvards were constructed under licence by the Noorduyn Aircraft Company in Montreal.

On the other side of the Bowesville Road across from the flying school, the Ottawa Car and Aircraft Company was in the process of erecting a new plant for the construction of parts for the Avro Anson twin-engine aircraft to be used for training bomber pilots.

On opening day, 5 August 1940, the Governor General was accompanied by a distinguished entourage, including Prime Minister King, Defence Minister Ralston, Air Minister Power, Air Vice Marshall Breadner, and Honorary Air Marshall W.A. (Billy) Bishop, VC. The twelve, yellow Harvard trainers were lined up in front of the hangars. In front of the aircraft was an honour guard standing at attention to take the salute of Earl Athlone. A RCAF band from Trenton played Land of Hope and Glory. After No.2 SFTS was declared open, the Harvard trainers were flown in various formations to the delight of the crowds there to witness the historic event.

In July 1941, a Warner Brothers crew from Hollywood filmed part of the feature movie Captains of the Clouds, starring James Cagney, at Uplands airfield. Billy Bishop played a cameo role in a “wings ceremony,” where actual pilots received their wings in a stirring graduation ceremony. You can see a preview of the movie on YouTube : Captains of the Clouds.

The BCATP was a huge success, training roughly 50 per cent of all Commonwealth airmen during the war. In addition to Canadian, British, Australian and New Zealand personnel, men from many other Allied countries received their flight training in BCATP schools, including Norwegians, Poles, Belgians, Free French, Czechs and Americans. In a 1943 congratulatory letter to prime minister King. US President Roosevelt called Canada “the aerodrome of democracy.” (As an interesting sidebar to history, Lester B. Pearson, then the number two person at the Canadian Embassy in Washington, was the person who coined the phrase—an allusion to Roosevelt naming the US the “arsenal of democracy” in a late 1940 speech. Breaking diplomatic protocol, the White House staff had contacted the Canadian embassy and had asked Pearson to help draft the latter.)

With an Allied victory on the horizon, the program started to be wound down in late 1944 and was terminated at the end of March 1945. During the BCATP’s time in operation, more than 131,553 aircrew graduated from 105 flight schools of various description at a cost of $2.23 billion (roughly $35 billion in today’s money). Of this amount, Canada paid $1.6 billion ($25 billion). While the cost was considerable, victory in the air was made possible by the BCATP.

In 1949, representatives from all countries that had participated in the BCATP paraded at RCAF Station Trenton to witness the unveiling of a set of wrought-iron gates given to Canada by the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, as a permanent memorial and a symbol of Commonwealth friendship and unity.

Sources:

Dunmore, Spencer, 1994. Wings for Victory, McClelland & Stewart, Inc. Toronto.

Evening Citizen, 1939. “Four Govts. Are ‘Well Pleased’ With Air Pact,” 19 December.

——————-, 1939. “Gives Further Details Of Air Training Plans,” 19 December.

——————-, 1940. “Governor-General Opens Empire Training School At Uplands Field,” 6 August.

——————, 1940. “Crowds Are Thrilled By Formation Flying,” 6 August.

Hatch, F. J., 1983. Aerodrome of Democracy: Canada and the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, 1939-1945, Department of National Defence, Directorate of History, Monograph Series No. 1.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Exercise Tocsin B-1961

13 November 1961

Tensions had been mounting between the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact partners and the United States and its NATO allies. In April 1961, some twelve hundred Cuban exiles, backed by the CIA and supplied with American arms and landing craft, had made a failed attempt to invade Cuba at the Bay of Pigs and topple Fidel Castro. The Cuban Communist leader had come to power two years earlier after having deposed Fulgencio Batista, the corrupt and repressive, American-supported dictator.

The following month, Canada tested its civil defence plans in the event of a nuclear war. In cities across the country, the wailing of more than two hundred sirens warned Canadians to take cover. The Canadian Emergency Measures Organization issued a booklet to households indicating what they could do in the event of a nuclear attack. Called The Eleven Steps To Survival, Canadians were told:

Step 1: Know the effects of nuclear explosions

Step 2: Know the facts about radioactive fallout

Step 3: Know the warning signal and have a battery-powered radio

Step 4: Know how to take shelter

Step 5: Have fourteen days emergency supplies

Step 6: Know how to prevent and fight fires

Step 7: Know first aid and home nursing

Step 8: Know emergency cleanliness

Step 9: Know how to get rid of radioactive dust

Step 10: Know your municipal plans

Step 11: Have a plan for your family and yourself

In the introduction to the booklet, Prime Minister Diefenbaker stated: Your personal survival can depend on you following the advice that is given and the survival of many others may depend on how well you have heeded the advice contained therein. The government also provided plans on how to build a backyard bomb shelter.

Mid-August, East Germany began the construction of the Berlin Wall cutting off West Berlin by land, and denying an escape route to the West by East Germans seeking freedom. In early September, the U.S. military detected four, above-ground Soviet nuclear explosions. Subsequently, radioactive fallout, 320 times higher than background radiation levels, was detected in Ottawa. Federal Health Minister Jay Monteith warned that should such high levels of radiation be maintained, they “could well be a hazard to health.” At a state banquet in Moscow, Indian Prime Minister Nehru told Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev that it would be stupid to start a war. Khrushchev replied that the Soviet people did not want war but “could not look on calmly while Western powers make military preparations on a hitherto unparalleled scale.” With war rhetoric rising, Prime Minister Diefenbaker warned Canadians in early November that “war is not as improbable as we hope,” and that if comes, Canada will be a battleground. Earlier he had told the House of Commons that should there be an attack on Canada, he and his wife would not leave Ottawa for safety but would rather take cover in the bomb shelter at 24 Sussex Drive.

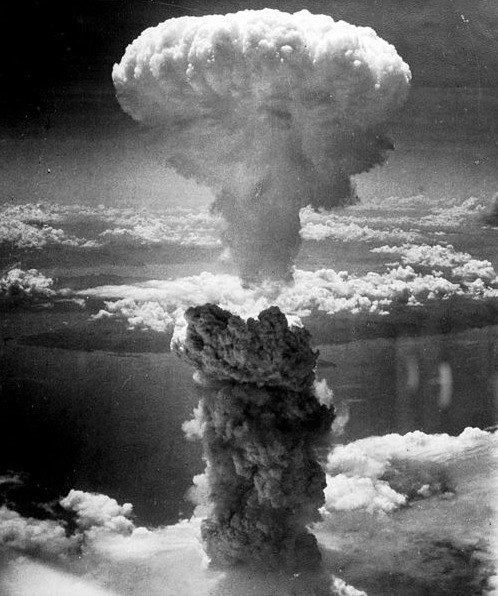

Atomic bomb explosion over Nagasaki, Japan, 9 August 1945, taken by Charles Levy

Atomic bomb explosion over Nagasaki, Japan, 9 August 1945, taken by Charles LevyDuring the morning of Monday, 13 November 1961, unidentified but presumed hostile submarines were detected in large numbers in the North Atlantic and in the Hudson Bay. Soviet tanker aircraft were also detected near the Aleutians. The Canadian armed forces increased it level of military alertness at 8.30am EST. This was stepped up to the next level at 10.30am and yet again at 12.30pm, sending staff to emergency centres across the country. Troops left possible target areas. At 2.30pm, key government officials and senior defence officers, including Defence Minister Douglas Harkness, Health Minister Monteith, Defence Production Minister Raymond O’Hurley, and Justice Minister Davie Fulton, were dispatched to Camp Petawawa, 150 kilometres north-west of Ottawa that was to become the government back-up centre in the event of war. (The underground, bomb-proof base in Carp now known as the Diefenbunker, which was designed to shelter the Governor General, the Prime Minister, and other senior government and military leaders in the event of nuclear war, was still under construction.)

At 6pm, the Canadian military was placed on maximum alert. Shortly afterwards, NORAD (North American Air Defense Command) radar spotted 36 hostile airplanes heading towards Canada between Greenland and Ellesmere Island. Another 20 were detected off the Aleutian Islands in the Pacific. At 6.50pm, Prime Minister Diefenbaker and six Cabinet colleagues went underground at 24 Sussex Drive where they issued an Order-In-Council invoking the War Measures Act. Defence Minister Harkness was appointed Acting Prime Minister and given almost dictatorial powers to respond if necessary. Diefenbaker also approved the signal to alert unsuspecting Canadians to the deteriorating military situation and to take shelter. He also prepared to address the nation across all radio and television stations in a special broadcast of the Emergency Measures Organization.

At precisely 7pm, more than 500 sirens from coast to coast, 45 in Ottawa alone, began a steady three-minute wail, their strident call telling citizens that a nuclear attack was expected. By that point, more than 110 “penetrations” of the Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line in Canada’s far north had been detected as Soviet bombers streaked across Canadian territory at 600 knots per hour. At 7.10pm, the Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) gave Diefenbaker a fifteen-minute warning that a missile attack was underway. Air raid sirens across the country gave the “take shelter” warning, a three-minute rising and falling sound that announced a nuclear strike was imminent.

It total, two waves of Soviet bombers, the first of 150 aircraft, the second of 110 as well as two waves of missiles, mostly heading for U.S. targets, were detected. Fourteen Canadian cities were destroyed by five-megaton nuclear bombs, including Vancouver and Courtney in British Columbia, Edmonton and Cold Lake in Alberta, Fort Churchill, Manitoba, Frobisher, NWT, North Bay, Sault Ste Marie, and Welland in Ontario, Chatham, New Brunswick, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Goose Bay in Labrador, and Stephenville on the Island of Newfoundland. Ottawa was destroyed at 10.10pm, with the epicentre of the blast situated just north of Uplands Airport. Toronto and Montreal were hit at 10.45pm and 10.51pm, respectively. The Soviet attack on North America lasted until 4am the next morning. Some 30 U.S. cities were destroyed, including Detroit, hit by a ten-megaton bomb that also killed tens of thousands in neighbouring Windsor.

The corner of Sparks Street and Elgin Street, Central Post Office, c. 1961, before and after a nuclear attack on Ottawa, Canada Emergency Measures Organization, Government of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4717891 and 4717352.

The corner of Sparks Street and Elgin Street, Central Post Office, c. 1961, before and after a nuclear attack on Ottawa, Canada Emergency Measures Organization, Government of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 4717891 and 4717352.

The death toll was staggering. The Army Operations Centre at Camp Petawawa estimated Canadian dead at roughly 2.6 million, including Prime Minister Diefenbaker, with an additional 1.6 million injured, many critically. Fire, radiation sickness, and exposure was expected to claims hundreds of thousands of additional lives in coming days and weeks. In the Ottawa region, the death toll was placed at 142,000 dead, 61,000 injured and 30,000 experiencing radiation sickness. On the upside, 90,000 people had been rescued though many thousands remained trapped in burning buildings and debris. Emergency teams of soldiers and hundreds of thousands of volunteers fanned out across the country to help the survivors. Jack Wallace, the Deputy Director of the Emergency Measures Organization noted that while the Saint Laurence Seaway system had been knocked out at Montreal, Welland, and Sault Ste Marie, the railway service could be quickly restored. While casualties were high, over 14 million Canadians had survived the multiple attacks. He also estimated that one half to two-thirds of industry could be quickly made operational and one-half of hydro power was still in commission. There was also sufficient food to feed all Canadians. Canada had come through the nuclear attack severely damaged but intact, with a nucleus of a national government still functioning at Camp Petawawa where fallout was considered light.

Thankfully, this horrific scenario was just that…a scenario called Exercise Tocsin B-1961 that played out on 13 November 1961 as part of Canada’s test of its emergency civil defences. However, all the events described leading up to the test are factual. While the test may seem fanciful to today’s Gen. “Xers” and Millennials, for those who grew up in the 1950s and 60s, it was very real. The Cold War was a time of great worry and stress. Exercise Tocsin B-1961 was held exactly one year before the Cuban missile crisis when the world held its breath as the United States and the Soviet Union played a high-stakes game of “chicken,” where one false movement by either side could have led to a global nuclear holocaust.

Sources:

Canadian Civil Defence Museum Association, “Steps to Survival,” http://civildefencemuseum.ca/.

Emergency Measures Organization, 1961. Eleven Steps to Survival, Ottawa: Queen’s Printer.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1961. “Tocsin B Alarm Goes Off Accidentally In Ottawa,” 13 November.

————————-, 1961. “Nuclear War Test: PM Among ‘Casualties’ As Toll Tops 3-Million,” 14 November.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1961. “Stupid To Start War Nehru Tells Khrushchev,” 7 September.

————————–, 1961. “Don’t Want War,” 7 September.

————————–, 1961. “War Not Impossible, PM Warns,” 10 November.

————————–, 1961. “Attack Warning Study Alarms Inside Buildings,” 13 November.

————————–, 1961. “Exercise Tocsin, Ottawa ‘Destroyed,’ 175,000 Toll.

————————–, 1961. “Cabinet Met Underground,” 15 November.

————————–, 1961. “Government Counts Tocsin Toll,”

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Grand Chaudière Dam

16 October 1868

We have in our very midst unrivalled water powers, and it would argue the utmost lack of energy, the blindest fatuity, were they to remain undeveloped. “Impressions of Ottawa,” Ottawa Citizen, 6 November 1860.

The mighty Ottawa River, also known as the Kichissippi in Algonquin and the Outaouais in French, stretches more than 1,100 kilometres. Its source is Lac Capitmichigama in central Quebec from which it runs west to Lake Timiskaming before heading south to form the boundary between Ontario and Quebec, passing through the National Capital Region on its way to meet the St. Lawrence at the Lac des Deux Montagnes in Montreal. Its watershed covers an area of more than 146,000 square kilometres.

For countless generations, the Ottawa was a key transportation and trading route for the Indigenous peoples of this land. Later, it became the route for European explorers and settlers into Canada’s interior. Led by native guides, Samuel de Champlain explored the Ottawa River in 1613. It subsequently became an important thoroughfare for French voyageurs and coureurs des bois trading manufactured goods with the First Nations for beaver and other pelts which were in high demand in Europe. Later still, loggers and lumbermen of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, who were exploiting the ancient forests of the Ottawa Valley, relied on the river to transport logs and square timber (logs that had been stripped of their bark and roughly squared) to markets.

With a vertical descent of 365 metres, the Ottawa River is turbulent and fast-flowing even today despite more than 50 dams and hydro facilities constructed along its main branch and tributaries. According to the Ottawa Riverkeeper, the Ottawa is one of the most regulated rivers in Canada. Nonetheless, it remains a magnet for white-water canoers and rafters.

For nineteenth century lumbermen trying to bring rafts of logs down the Ottawa, its rapids and falls were a nightmare, posing dangers to life and limb. However, the entrepreneurs of Ottawa and Hull saw the potential for profit from those same rapids and falls if they could be harnessed to produce the motive power necessary to drive the big saws that processed the raw lumber. By damming the Ottawa, mill owners could channel the flow of water through their mills. A tamed river also meant a safer river for the log drivers.

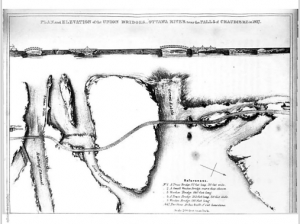

One of the major obstacles on the Ottawa River was the Chaudière Falls, known as the Giant Kettle in English. In 1829, Ruggles Wright, the son of Philemon Wright who founded Hull, built a timber slide on the Quebec side of the river to permit logs and rafts of timber to bypass the falls. Three years later, another slide was constructed by George Buchanan on the Ontario side of the river. To build the slide, a dam was constructed that ran roughly parallel to the shore to divert water into a channel. (The dam can be seen in an 1832 plan of the first Union Bridge across the Ottawa River by Joseph Bouchette.)

In 1854, at the behest of the mill-owners and lumbermen of Bytown, the Department of Public Works of the Provincial Government, constructed a 640-foot dam with log booms on the south side of the Chaudière Falls. It extended from the pier built by George Buchanan at the head of his timber slide to Russell Island above the Falls. The purpose of the dam was threefold. First, it would provide a more constant supply of water during the low water summer months. Second, it would furnish a 140-acre pool of calm water for the storage of logs waiting to be processed in the adjacent mills. Previously, only a day’s worth of logs could be stored. Third, it would reduce the loss of timber inadvertently going over the Falls. It was reported that £3,000 pounds worth of logs was lost annually owing to the timber cribs getting into the wrong channel. There was no mention of the fate of the men driving the logs.

A second dam with booms was also constructed on the north side of the river to ensure a constant supply of water for the Hull mills. According to the Citizen, “There is no limit to the extent of the commerce that may be created by the mills and factories that can be put into motion by the water of the Chaudière.”

Despite the hyperbole, the newspaper was on to something. Between 1856 and 1860, the timber industry expanded rapidly with Messrs. Perley, Booth, and Eddy joining timber pioneers such as Messrs. Baldwin, Bronson, Harris, and Young. The mill-owners sought more River “improvements” to expand their capacity. Reportedly, the lumber barons, to whom the government had leased water rights, were “exceedingly irritated and annoyed” to go with out water for their mills during the low water summer months while at the same time “a mighty volume of water [was] plunging over the Falls.” With many mills forced to close for part of the year, there was a loss of profit, especially as mill owners tried to keep skilled workers on payrolls as long as possible fearing that they might leave the region if they were laid off. Even so, many found themselves temporarily unemployed during the low water months—a serious condition as there was no unemployment insurance. The Citizen opined that “fathers of families, others younger—the hope and strength of the country—[were] standing idle, in want of work…while the mighty volume of the Ottawa rushed by the silent mills uncurbed and useless to man.”

Mr. Baldwin proposed that the government build a submerged dam across the main channel a few hundred yards above (west of) the Chaudière Falls, to divert the river towards the lumber mills. However, excess water would continue to flow over the dam during periods of high water and avert spring flooding. The government was not convinced. To allay governmental concerns about potential flooding, Baldwin suggested lowering Russell Island, located at the south end of the proposed dam, by six feet to provide an additional area of discharge during periods of high water. During low water, it would stand above the waterline and would act as an auxiliary dam. He figured that the water running over the lowered island during the spring freshet would offset the obstruction caused by the proposed dam. Still unconvinced, the Department of Public Works refused to fund the project and demanded the backers of the project, should they go ahead themselves, provide bonds of indemnity to compensate landowners who might be flooded by the dam.

With the capital for the venture provided by “a large party of the leading residents of the city and others,” the project went ahead under the supervision of Mr. John O’Connor during the fall of 1868. The submerged dam was 350 feet long and 75 feet wide at the base, tapering to 24 to 48 feet wide at the top. It was built of strong crib-work filled in with stone and braced with longitudinal timbers faced with 5-inch thick planks upon which guard timbers were attached using iron bolts. Guard piers protected each end of the dam. Reportedly, workers excavated 8,000 tons of rock, presumably from Russell Island. The project costed roughly $10,000, and was completed in five weeks using a workforce of 200 men.

The Grand Chaudière Dam was inaugurated on 16 October 1868, a day which the Citizen said would be “long remembered in the annals of the lumber interest of the valley.” The paper also praised the “enterprise of our American citizens—by whom the majority of the milling establishments at the Chaudière are owned.”

A few days later, sixty of the leading citizens of Ottawa assembled on Russell Island for a celebration to mark the completion of the dam, “and pledge a bumper to the health of the builder, and prosperity to the trade.” Chairing the gathering was Richard Scott, the Liberal member of the legislative assembly who represented Ottawa in the Ontario legislature. Other attendees included, Joseph M. Currier, the Conservative member of parliament for the City of Ottawa, Mayor Henry Friel, and a number of Dominion Government cabinet ministers despite the government’s earlier opposition to the project. Samuel Tilley, the Minister of Inland Revenue, apologized for the absence of Sir George Cartier and others who could not attend owing to important engagements elsewhere. James Skead, a prominent area businessman and senator, argued that similar works like the Chaudière dam were needed elsewhere on the Ottawa River.

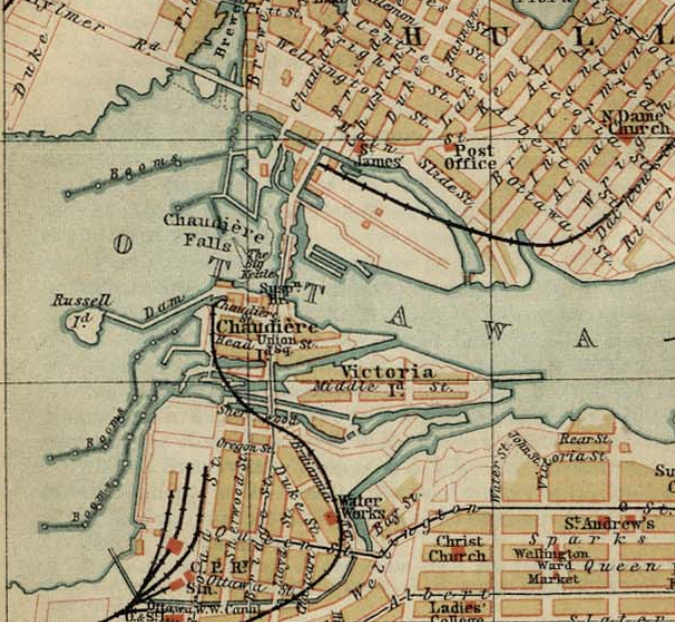

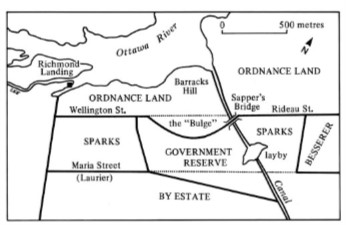

Map of the Chaudière area before the construction of the Chaudière Ring dam in 1908. The 1854 dam between Chaudière Island and Russell Island can be seen in the middle left of the map. The Grand Chaudière Dam is not visible.The impact on timber production owing to the construction of the Grand Chaudière Dam was considerable. Reportedly, the small mill owned by Mr. Young increased its monthly production by 1 million feet of lumber, the product of 5,000 standard logs, during the first dry season after the completion of the dam. Extrapolating these figures to include the much larger operations of Messrs. Baldwin, Bronson, Booth and Perley, the Citizen calculated that a total of 13 million additional feet of lumber were produced every month during the dry season. With a dry season averaging three months, the value of increased production amounted to an estimated $507,000 dollars—a huge sum. As well, there was no flooding during the spring freshet as feared by the government. The expectations of the dam’s backers were more than fully met.

Map of the Chaudière area before the construction of the Chaudière Ring dam in 1908. The 1854 dam between Chaudière Island and Russell Island can be seen in the middle left of the map. The Grand Chaudière Dam is not visible.The impact on timber production owing to the construction of the Grand Chaudière Dam was considerable. Reportedly, the small mill owned by Mr. Young increased its monthly production by 1 million feet of lumber, the product of 5,000 standard logs, during the first dry season after the completion of the dam. Extrapolating these figures to include the much larger operations of Messrs. Baldwin, Bronson, Booth and Perley, the Citizen calculated that a total of 13 million additional feet of lumber were produced every month during the dry season. With a dry season averaging three months, the value of increased production amounted to an estimated $507,000 dollars—a huge sum. As well, there was no flooding during the spring freshet as feared by the government. The expectations of the dam’s backers were more than fully met.

With the mills working at full capacity from the beginning to the end of the milling season, the Citizen wrote: The completion and successful working of the dam may be said to be the crowning point of numerous victories over great natural obstructions and difficulties. The vast water power which has for ages been conserved in the Chaudière Falls, has now been utilized to an extent which few of the last generation ever dreamt of, and which but few of the present generation, who thoroughly understood the difficulties, could, a few years ago, have supposed could be realized.

Today, the Grand Chaudière Dam, which permitted a huge expansion of the Ottawa timber business during the second half of the nineteenth century, is long gone. It was replaced by the Chaudière Ring Dam in 1908 which massively expanded the hydro-electric generating capacity of the Chaudière Falls, and provided the bulk of Ottawa’s electricity during the early twentieth century.

Sources:

Haxton Tim & Chubbuck, Don, 2002, Review of the historical and existing natural environment and resource uses on the Ottawa River, Ontario Power Generation, www.ottawariverkeeper.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/tim_haxton_report.pdf.

Ottawa Citizen, 1854. “No Title,” 29 July.

——————, 1854. “Ottawa Improvements,” 7 October.

——————, 1854. “Public Works On The Ottawa,” 28 October.

——————, 1868. “Inauguration Of The Great Chaudiere Dam,” 23 October.

——————, 1869. “The Pubic Works on the Ottawa And Its Tributaries,” 12 August.

——————, 1869. “The Lumbering Interests Of Ottawa, 16 August.

Ottawa Riverkeeper, 2019. Dams, www.ottawariverkeeper.ca/home/explore-the-river/dams/.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Anishinabek

Time immemorial and 7 October 1763

Canada is widely viewed as a young country, its history stretching back no more than a few hundred years to the arrival of French and British settlers to its shores. But this is a very blinkered view of things. The territory that we now call Canada was not terra nullius when the Europeans arrived, far from it. It was instead populated by a diverse group of Indigenous peoples with their own cultures, traditions and languages from the Pacific Ocean in the west, to the shores of the Arctic Ocean in the north, the Great Lakes in the south, and to the Atlantic Ocean in the east. Pre-contact population estimates vary widely, but modern estimates place the population of the Pacific Northwest alone at as much as 500,000. One, therefore, wonders what the population of the entire territory that was to become Canada might have been. Sadly, European traders and settlers brought diseases, such as smallpox, to which the native population had little or no resistance. Whole communities were virtually wiped out within a short period of time. By 1867, the Canadian Indigenous population had fallen to about 125,000 souls, out of a total Canadian population of about 3.7 million, and was to continue to fall for decades after.

Nobody could live in the Ottawa region until the glaciers of the Wisconsin glacial episode had retreated sufficiently to expose the territory. This occurred roughly 11,000 years ago. Recent archaeological work has found traces of humans dating back as much as 8,000 years. Excavations at several locations along the Ottawa River have uncovered many artifacts fashioned by the Laurentian people of the Archaic period. These included the discovery of spear throwers on Allumette Island in Quebec close to Pembroke, Ontario. These implements enabled hunters to propel spears with greater force than relying on muscle power alone. Also found were tools made of stone and bone, knives crafted from slate and copper, scrapers, harpoons, fish hooks, awls and finely-made needles, the latter requiring a high degree of sophistication to manufacture. On Morrison Island, also close to Pembroke, hundreds of grinding stones were found along with axes, drills, and adzes. These early residents were highly skilled and had a strong artistic sensibility. Many bone articles had been delicately engraved.

The archaeological record also shows a continuous human presence right in the National Capital Region since those early days, reflective of its strategic position at the confluence of three major river systems—the Ottawa which flows into the St. Lawrence and from thence to the Atlantic; the Gatineau which extends northward for almost 400 kilometres; and the Rideau which, via a series of portages, provides access southward to the Great Lakes. These waterways were major transportation and trade routes for indigenous peoples, and continued as such well after the arrival of European settlers at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Indeed, the Rideau Canal built in the late 1820s traced the well-travelled indigenous route from Lake Ontario to the Ottawa River.

Indicative of the importance of the region as a trading centre, archaeological digs in the National Capital Region have uncovered an extraordinary range of material brought many hundreds if not thousands of kilometres. These include quartzite from central Quebec, different types of chert (a type of rock) used for making tools from the Hudson Bay, Illinois, and Ohio, ceramics from south of the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron, and copper from the western edge of Lake Superior. Today’s Leamy Lake Park appears to have been a key stopping point with evidence indicating continuous seasonal occupation of the delta at the mouth of the Gatineau River for over 4,500 years. There, indigenous people from all over stopped to meet, trade, and enjoy the rich bounty of natural resources to be found there.

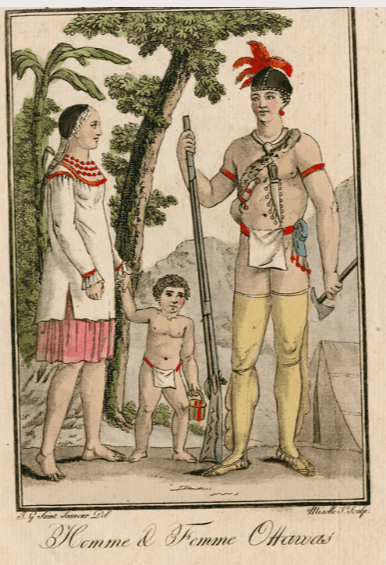

Ottawa First Nation family, J.G. de Sauveur, Engraving, 1801, Library and Archives Canada, 2937181.Other excavations, pioneered by Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, a prominent Bytown physician, identified in 1843 an “Indian burial ground” on the northern shore of the Ottawa River. He uncovered the remains of twenty individuals in communal and individual graves. Also found at this site were ashes from cremations. Recent investigations during the twenty-first century have confirmed the location of the site as Hull Landing, immediately opposite Parliament Hill, now the location of the Canadian Museum of History.

Ottawa First Nation family, J.G. de Sauveur, Engraving, 1801, Library and Archives Canada, 2937181.Other excavations, pioneered by Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, a prominent Bytown physician, identified in 1843 an “Indian burial ground” on the northern shore of the Ottawa River. He uncovered the remains of twenty individuals in communal and individual graves. Also found at this site were ashes from cremations. Recent investigations during the twenty-first century have confirmed the location of the site as Hull Landing, immediately opposite Parliament Hill, now the location of the Canadian Museum of History.

We also know that the Chaudière Falls was a site of considerable spiritual significance to the Indigenous peoples of the region. In 1613, Samuel de Champlain described in his journal the “usual” ceremony that was celebrated at that site. He wrote that after the people had assembled, and a speech given by one of the chiefs, an offering of tobacco on a wooden plate was thrown into the roiling waters of the cauldron to seek the intercession of the gods to protect them from their enemies.

It was Samuel de Champlain who popularized the name for these indigenous peoples—the “Algoumequins” a.k.a. the Algonquins. But the people knew themselves as the Anishinabek, sometimes translated as true men, or good humans.

Following first contact with Europeans at the beginning of the seventeenth century, many eastern First Nations became embroiled in the seemingly endless conflicts between European powers for political and economic ascendancy in North America. The semi-nomadic Algonquins, who were superb hunters and trappers, became key partners with the French in the European fur trade. They supplied pelts from their own extensive territories in the Ottawa and St. Lawrence Valleys, or acted as middlemen for the Cree to the north. In exchange, the Algonquins received firearms that they used to defend themselves from their traditional rivals, the Iroquois First Nations, who were important allies of Dutch settlers to the south, and subsequently the English.

These European struggles culminated in the long conflict between England and France in the mid-eighteenth century, called the Seven Years’ War, which ultimately led to an English victory and France’s loss of its North American colonies with the exception of the important fishing centres on the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon located in the mouth of the St. Lawrence close to Newfoundland.

When Montreal capitulated in 1760 to English forces, the English agreed to a French condition of surrender that their indigenous allies could remain in their traditional territories and would not be molested. Three years later, in June 1763, France ceded its North American territories to the English under the Treaty of Paris.

On 7 October 1763, King George III issued a Royal Proclamation outlining how his new territories in North America would be administered and how relations with the Indigenous communities would be undertaken. The Proclamation stated: “And whereas it is just and reasonable, and essential to our interest and the Security of the Colonies, that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians, with whom We are connected, and who live under our Protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having ceded to, or purchased by Us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds.”

Another provision of the Proclamation forbade private purchases of land from Indigenous peoples, with this right reserved to the Crown. This provision set the basis for the negotiation of future treaties between the Crown and Canada’s indigenous peoples.

Notwithstanding this 1763 Royal Proclamation, Europeans quickly settled on indigenous territories. Following the American War of Independence, which ended in 1783, the Crown gave grants of land to Loyalist refugees coming north to Canadian territory according to their rank and service. These grants were given without the consent of the First Nations.

Here in the greater Ottawa area, Loyalists received grants of land on the Rideau River, including at such places as today’s Merrickville, Burritt’s Rapids, and Smiths Falls. Grants of land along the Ottawa River from Carillon westward to Fassett on the north shore in Quebec and at Hawkesbury in Ontario were also handed out.

In addition, European settlers began settling on indigenous territory in the National Capital Region in 1800 with the arrival of Philemon Wright in what is now the Hull sector of Gatineau. Initially hoping to farm, settlers almost immediately began to exploit the seemingly inexhaustible supply of pine for sale in the United Kingdom and later the United States. Settlement accelerated with the building of the Rideau Canal and the naming of Ottawa as the capital of Canada in 1857.

The clearance of vast tracks of land for farms, lumbering and urban development irrevocably altered the landscape of the Ottawa Valley. By the 1920s, less than four percent of the original, old growth forest was left. For the Algonquins, who had lived for untold centuries in harmony with nature, their way of life was also irrevocably changed. As no treaty had been made with the Crown, the Algonquin First Nations had been marginalized on their own territory. Canada’s capital continues to sit on unceded Algonquin territory in contravention of the 1763 Royal Proclamation.

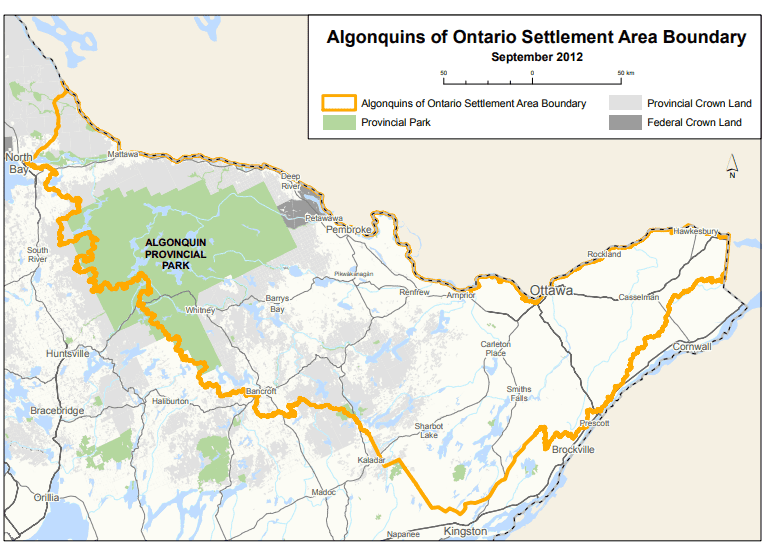

Territorial claims of the Ontario Algonquins, Province of Ontario.

Territorial claims of the Ontario Algonquins, Province of Ontario.

Today, there are ten recognized Algonquin First Nations with a total population of about 11,000. Nine Algonquin communities are in Quebec—Kitigan Zibi, Barriere Lake, Kitcisakik, Lac Simon, Abitibiwinni, Long Point, Timiskaming, Kebaowek, and Wolf Lake. The tenth, Pikwakanagan, is located in Ontario. There are three additional Ontario First Nations that are related by kinship—the Temagami, the Wahgoshig and the Matchewan.

In October 2016, the Algonquins of Ontario reached an agreement-in principle-with the federal government and the government of Ontario to settle all land claims covering some 36,000 square kilometres of land in the watersheds of the Ottawa and Mattawa with a population of 1.2 million. Algonquin territorial claims in Quebec were not covered by the agreement. The agreement-in-principle is viewed as a major milestone towards reconciliation and renewed relations. If ratified, the agreement would lead to the transfer of 117,500 acres of provincial Crown land to Algonquin ownership, the provision of $300 million by the federal and provincial governments, and the definition of Algonquin rights related to lands and natural resources in Ontario. No land will be expropriated from private owners. The agreement would be Ontario’s first, modern-day, constitutionally protected treaty. As of time of writing (2021), a final agreement had not yet been reached.

Sources:

Algonquins of Ontario, 2021. Our Proud History.

Belshaw, John Douglas, 2018. “Natives by Numbers,” Canadian History: Post Confederation, BC Open Textbook Project.

Boswell, Randy & Pilon, Jean-Luc, 2015. The Archaeological Legacy of Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 39: 294-326.

Di Gangi, Peter, 2018. Algonquin Territory, Canada’s History, 30 April.

Hall, Anthony, J. 2019. Royal Proclamation of 1763, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 7 February 2006.

Hele, Carl. 2020. Anishinaabe, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 16 July.

Ontario, Government of, 2021. The Algonquin Land Claim.

Neville, George A. 2018. Loyalist Land Grants Along the Grand (Ottawa) River 1788, Bytown Pamphlet, No. 103, Historical Society of Ottawa.

Pelletier, Gérard, 1997. “The First Inhabitants of the Outaouais; 6,000 years of History,” History of the Outaouais, ed. Chad Gaffield, Laval University.

Pilon, Jean-Luc & Boswell, Randy, 2015. “Below the Falls; An Ancient Cultural Landscape in the Centre of (Canada’s National Capital Region) Gatineau,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 39 (257-293).

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Chaudière Bridges

28 September 1826

Bridges are amazing structures. Spanning rivers, gorges, bays and even open ocean, they are testaments to the ingenuity of the engineers who designed them and the courage and ability of the workers who constructed them. Who hasn’t crossed a bridge and wondered what’s holding it up and experienced a frisson of excitement or even terror? The longest bridge in the world over water connects Hong Kong to Macau and the city of Zhuhai on the Chinese mainland, a distance of 55 kilometres, of which a 6.7-kilometre stretch midway is an under-water tunnel between two artificial islands to allow ocean-going ships to travel up the Pearl River estuary. It opened in 2018. Canada’s Confederation Bridge, which links Prince Edward Island to New Brunswick, is 12.9 kilometres long. At the other extreme is Bermuda’s Somerset Bridge that connects Somerset Island with the “mainland.” Dating back to 1620, it is reputedly the smallest drawbridge in the world. Operated by hand, it is just wide enough to allow a mast of a sailboat travelling between the Great Sound and Ely’s Harbour to pass through the gap.

In Canada’s capital, six bridges span the mighty Ottawa River: the Alexandra (or Interprovincial) Bridge; the Champlain Bridge; the Chaudière Bridge; the Macdonald-Cartier Bridge; the Portage Bridge; and the Prince of Wales Bridge (now closed). While the current Chaudière Bridge dates from 1919, it is the site of the first and for a long time the only bridge across the Ottawa River.

The need for a bridge crossing the Ottawa River became apparent after work commenced on the Rideau Canal in the summer of 1826 under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel John By of the Royal Engineers. With only wilderness on the Upper Canada side, workers and supplies had to be ferried across the river from Wright’s Town (later known as Hull) in Lower Canada, the only settlement of any consequence in the region, where labourers were billeted and shops and stores could be had. (American Philemon Wright had founded Wright’s Town in 1804.) As this was unsatisfactory to all, Colonel By and his engineering colleagues decided to build a bridge as quickly as possible, their haste probably encouraged by the approach of winter.

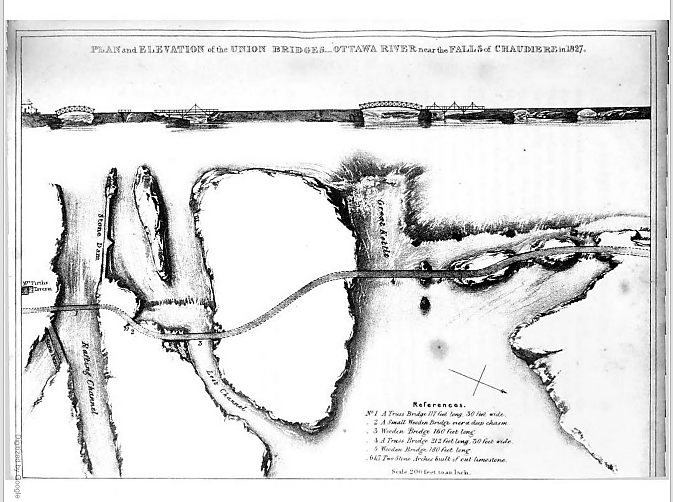

Plan and Elevation of the Union Bridge in Joseph Bouchette, The British Dominions in North America, London, 1832.

Plan and Elevation of the Union Bridge in Joseph Bouchette, The British Dominions in North America, London, 1832.

Their plan was to build a series of bridges to link Lower Canada on the northern shore of the Ottawa River to Upper Canada on the southern shore at the Chaudière Falls where the river temporarily narrows, using the islands mid-river as stepping stones. All were to be made of stone and masonry except for the widest section which was to be made of wood given the width of the gap, the depth of the water and the speed of the current. Col. By later modified this plan. Five of the seven bridges were made of wood—(from south to north over the river,) a 117-foot truss bridge, a small bridge over a deep chasm, a 160-foot bridge, a 212-foot truss bridge, a 180-foot bridge, and two limestone bridges.

After a quick survey—these were the days long before environmental assessments—construction began. On 28 September 1826, General George Ramsay, 9th Earl Dalhousie and Governor General of British North America, placed several George IV silver coins under a foundation stone on the Lower Canadian shore. Colonel Durnford of the Royal Engineers, Colonel John By, and a number of prominent area landowners, including Nicholas Sparks, Thomas McKay and Philemon Wright, attended the ceremony.

Three weeks into the construction, the first masonry arch on the Lower Canada side collapsed when the temporary supporting falsework was removed. Colonel By ordered work to recommence immediately with new plans drawn up by Thomas Burrowes, the assistant overseer of works. The new, hammered stone arch was completed by early January 1827 despite atrocious working conditions. Spray from the nearby falls froze thickly onto the workers’ clothes despite rough wooden screens being installed to shelter them. The second arch was finished by the summer of 1827.

The biggest challenge was bridging the Chaudière itself, also known in English as the Giant Kettle. To link its two sides, Captain Asterbrooks of the Royal Artillery fired a brass cannon loaded with a ½-inch rope to workmen on Chaudière Island. Twice he failed, the rope breaking. But he succeeded with a 1-inch rope. Once workers had a hold of it, they were able to haul over larger cables. Two ten-foot wooden trestles were constructed on either side with ropes stretched over their top and fastened to the rocks. The workers fashioned a precarious footbridge with a rope handrail. It swayed in the wind and sagged to within seven feet of the raging torrent beneath it. It must have been terrifying to cross. In his 1832 book The British Dominions in North America, Joseph Bouchette wrote: “We cannot forebear associating with our recollections of this picturesque bridge the heroism of a distinguished peeress [Countess Dalhousie], who we believe, was the first woman to venture across it.” The bridge’s ropes were then replaced with stronger chains. But as workmen were planking the floor of the bridge, the last step in its construction, disaster struck. First one then the other chain broke, throwing men and their equipment into the raging torrent. While accounts vary, as many as three men drowned.

Undeterred by the tragedy, Colonel By immediately got back to work. This time, workmen constructed stronger trestles and bridged the gap with two 8-inch link chain cables. Two large scows, a type of flat-bottomed boat, were built and moored securely in the location of the bridge. Jack screws placed on the scows supported the bridge during its construction. Unbelievably, just prior to the bridge’s completion, a strong gale flipped it over. Workmen were obliged to cut the bridge free which sent it sailing down the Ottawa river, coming to land close to the entrance of the Rideau Canal. Reportedly, the Chief workman, Mr. Drummond, shed tears in frustration.

Again, Colonel By persevered; his next bridge held. Supported by chains made of 1 3/4-inch thick iron and 10-inch links, the wooden bridge was 212 feet long, 30 feet wide and roughly 40 feet above the water, high enough to escape damage during the spring freshet. It was completed in the summer of 1828, two years after construction had commenced. Upper and Lower Canada were finally united. Fittingly, Col. By called it the Union Bridge.

Lieutenant Pooley, who worked for Col. By, supervised the construction of a final bridge needed to connect Bytown with the new Union Bridge. This bridge spanned a “gully” in what became LeBreton Flats. So impressed was Col. By with Pooley’s round-log bridge that he dubbed it “Pooley’s Bridge.” This name stuck. Lieutenant Pooley’s wooden bridge was replaced by a stone bridge in 1873. It was designated a heritage structure in 1982.

As the Union Bridge was funded by the Imperial Government, Colonel By instituted a toll to help pay for it. The cost was one penny per person, one penny for every horse, ox, cow, sheep and pig, and two pennies for every wagon and sleigh. This was a pretty steep tariff for the times.

Sadly, the Union Bridge did not last. In May 1836, it collapsed into the river and was swept away. Fortunately, there was nobody on it at the time. Again, the only way across the Ottawa River was by ferry.

This all changed in 1843 when the Union Suspension Bridge, constructed by Mr. Wilkinson, an American, opened for traffic. The bridge had a span of 242 feet. Its iron wire suspension cables, which were imported from Britain to Montreal and ferried to Bytown in barges, supported an oaken plank deck. It was the first of its kind in Canada, and was considered an engineering marvel of the age. The Packet opined that the bridge was “a beautiful piece of work” and that it “reflects great credit to the builder, Mr. Wilkinson.” A big celebration was held at Doran’s Hotel on Wellington Street to mark its opening. Engraved invitations were sent out to guests to attend the “Union Suspension Bridge Ball,” complete with a picture of the completed bridge.

Union Suspension Bridge, Watercolour by F. P. Rubidge, Library and Archives Canada, Arch. Ref. R182-2.

Union Suspension Bridge, Watercolour by F. P. Rubidge, Library and Archives Canada, Arch. Ref. R182-2.

Like its predecessor, the Union Suspension Bridge charged tolls. It was a profitable business. In the June to September period of 1851, Duncan Graham, appointed the (tax) Collector for Bytown in the Finance Department by Earl Cathcart, collected £303. 6s. 7d. (equivalent to more than $1,650) in tolls. This was almost enough to cover his annual salary of $1,500 and the monthly stipend £6. 5s. of Mr Mossop, the bridge keeper, who lived in the toll house rent free. Later, the government put the toll business out to tender. At the 1869 tender, the government set a reserve price of $2,000. This compares with annual tolls collected in the 1865-1868 period ranging from $2,500 to $3,350. The winner of the auction was required to maintain the toll house, and keep the bridge clean of rubbish. In winter, they were also responsible for snow clearance, but were required to leave six inches to facilitate sleigh traffic.

Bridge maintenance was not up to everybody’s standards. People complained that the bridge was dangerous especially at night as its railings were low and weak. “Persons run a very great risk on a dark night of driving into the ‘Devil’s Punch-bowl’” said the Ottawa Citizen. As well, the approaches to the bridge on either side of the river were nearly impassable during rainy weather owing to “the enormous quantity of mud and water collected.” In an agreement with the City, the Dominion government abolished tolls on the Union Suspension Bridge in 1885.

The muddy and rutted entrance to the Union Suspension Bridge, looking towards Ottawa, Topley Studio, c. 1867-70, Library and Archives Canada, PA-012705.In 1889, the Dominion government appropriated $35,000 for a new iron truss bridge to replace the deteriorating Union Suspension Bridge. Messrs. Rousseau & Mather were the contractors. Work commenced at the beginning of August and was completed by the beginning of December of that year. Many were concerned that the 30-foot width of the new roadway was too narrow given the growing amount of traffic between Ottawa and Hull. Appeals to the government to widen the bridge or at least put the two 5-foot sidewalks on the outside of the trestles in order to increase the width of the roadway by 10 feet fell on deaf ears.

The muddy and rutted entrance to the Union Suspension Bridge, looking towards Ottawa, Topley Studio, c. 1867-70, Library and Archives Canada, PA-012705.In 1889, the Dominion government appropriated $35,000 for a new iron truss bridge to replace the deteriorating Union Suspension Bridge. Messrs. Rousseau & Mather were the contractors. Work commenced at the beginning of August and was completed by the beginning of December of that year. Many were concerned that the 30-foot width of the new roadway was too narrow given the growing amount of traffic between Ottawa and Hull. Appeals to the government to widen the bridge or at least put the two 5-foot sidewalks on the outside of the trestles in order to increase the width of the roadway by 10 feet fell on deaf ears.

Twelve years later in 1900, the Great Fire, which destroyed much of Hull and LeBreton Flats, severely damaged the bridge. A vital thoroughfare, the government moved quickly to repair it.

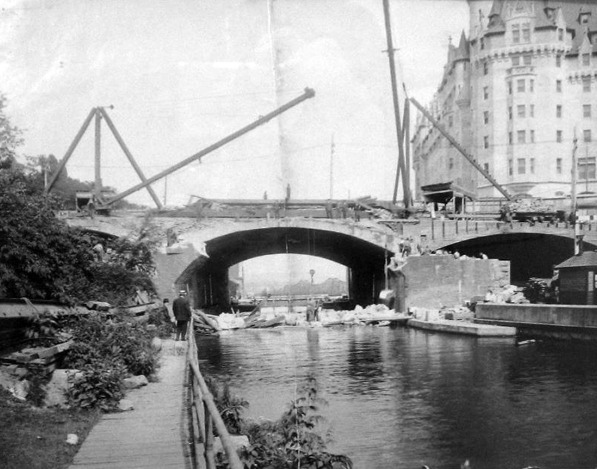

In 1919, the Government condemned the Chaudière bridge as being unsafe. According to the Citizen, just walking over the old bridge was enough to give one “thrills” owing to its “see-saw motion when cars pass over it.” Dominion policemen ensured that too many vehicles didn’t try to cross the bridge at the same time. The replacement bridge was built by the Dominion Bridge Company at a cost of $110,000. It was assembled on the Quebec side and was moved into place using scows. This time, government listened to its critics, and placed the sidewalks on the outside of the piers. Before the new Chaudière bridge was put into position, the old bridge was lifted by four 50-ton hydraulic jacks, placed on rollers, and moved 50 feet downriver to a temporary location so that traffic across the river would not be unduly impeded by the construction.

In 2008, the Chaudière bridge was temporarily closed when an inspection revealed that its stone arches, some of which date back to that first 1820’s bridge, were no longer safe. Following repairs, the government reopened the bridge the following year. It continues to serve thousands of commuters every day.

Sources:

Bouchette, Joseph, 1832. The British Dominions in North America, Vol. 1, London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green and Longman.

Bytown Gazette, 1846. “No title,” 14 September.

Canada, Province of, 1867. Report of the Minister of Agriculture for 1866, Ottawa: Hunter, Rose & Company.

Mika, Nick & Helma, 1982. Bytown, The early day of Ottawa, Belleville: Mika Publishing Company.

Ottawa Citizen, 1868. “Editorial,” 19 June.

——————, 1869. “Tolls on Union Suspension Bridge,” 26 July.

——————, 1908. “Civil Servants’ Income Tax,” 17 February.

——————, 1919. “Chaudiere Bridge Gives One Thrills,” 18 August.

——————, 1919. “Are Moving The Old Chaudiere Bridge,” 21 August.

——————, 1929. “Ottawa’s First Bridge And Other Narrations,” 12 October.

——————, 1933. “Chaudiere Toll Bridge 1851, Document Tells of Revenue,” 5 August.

——————, 1981. “By-Gone Days,” 28 February.

Ottawa Journal, 1889,” Supplementary Estimates,” 24 April.

——————, 1889. “The Chaudiere Bridge,” 19 September.

Packet (The), 1847. “The Ottawa-Slides-Steamers-Railroads-Necessary Improvements, etc.” 12 June.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa at War

3 September 1939

It was the Labour Day weekend, the last long weekend of the summer. But, instead of sleeping late or basking in the sun, Canadians were huddled around their radios, anxiously listening to news coming out of London. Shortly after 6am in Ottawa (11am London time) on Sunday, 3 September, 1939, Neville Chamberlain, the British Prime Minister, announced over the wireless that Great Britain was at war with Germany. The ultimatum that the British ambassador had delivered to the Reich’s Foreign Ministry in response to the German invasion of Poland had gone unanswered.

The news was not unexpected. For weeks the martial drumbeat had grown louder. With Germany and the Soviet Union signing a non-aggression pact in mid-August, there was nothing stopping the Nazis from attacking Poland. With a swift victory almost assured over the antiquated Polish army, Germany no longer risked a two-front war should Britain and France honour their pledge to support Poland. At the beginning of September, German forces entered Poland.

Unlike twenty-five years earlier, there were no shouts of joy and applause at the British declaration of war. Ottawa took the news somberly. Later that Sabbath morning, families went to church to pray for divine guidance for their leaders and protection for their families and friends in the perilous times ahead. In the early afternoon, families again gathered around the radios, this time to hear the King say: “I now call my people at home and my peoples across the seas who will make our cause their own. I ask them to stand calm and firm and united in this time of trial.” The Citizen reported that people wept hearing him speak. “It was the message of a beloved sovereign to a people with whom he and his Queen had mingled freely but a few short months ago [the 1939 Royal Visit] …It was as if His Majesty in truth had crossed the threshold of every Canadian home to bid them his good cheer in the extremity of the hour.”

Prime Minister Mackenzie King was awoken early with the news of Britain’s declaration of war. He hurried from Kingsmere, his country estate in the Gatineau Hills, to Ottawa for a 10 o’clock emergency Cabinet meeting in the Privy Council Chamber in the East Block on Parliament Hill. Meanwhile, instead of the usual Sunday quiet, Sparks Street buzzed with excitement as hundreds of anxious people milled about in front of the Citizen’s office waiting for the latest news bulletins to be posted. Extra police were laid on to control the crowd. Over that long weekend, Ottawa troops were mobilized with gunners moving into Lansdowne Park. Guards appeared on all public utilities and local dairy plants to prevent possible sabotage. Placards went up across the city saying men of military age were needed. The Cameron Highlanders announced that men should report to the Cartier Drill Hall at 9am on the Monday morning. The drum and bugle band of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps marched through Ottawa streets, with placards saying “Recruits wanted for the RCASC, mechanics, tinsmiths, coppersmiths, clerks, turners.”

When Mackenzie King left the Cabinet meeting around 2pm Sunday afternoon, the large crowd waiting for him outside the East Block cheered. The Prime Minister doffed his hat in acknowledgement and then paused for an official photograph to be taken by the Government Motion Picture Bureau for posterity. At 5.30pm, Mackenzie King spoke to the nation from the CBC broadcasting studio in the Château Laurier Hotel. Justice Minister Lapointe subsequently spoke in French. Mackenzie King promised that Canada would co-operate fully with the Motherland and urged Canadians to “unite in a national effort.” He added that “There is no home in Canada, no family and no individual whose fortunes and freedom are not bound up in the present struggle.” Parliament would debate the situation in Europe the following Thursday (7 September).

While both major Ottawa newspapers considered Canada to be at war, the country was actually in a strange limbo, neither officially at war nor really at peace. Since the passage of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, Canada was an autonomous Dominion within the British Empire. Consequently, unlike in 1914, a declaration of war by Britain did not automatically mean Canada was at war. Although both Australia and New Zealand had followed with their own declarations of war immediately after that of Britain, Mackenzie King held back awaiting the Parliamentary debate. The government was making a constitutional statement, underscoring Canadian autonomy. It also mattered practically. While the United States had immediately stopped all deliveries of arms to Britain (and Germany) due to its “Neutrality Act,” which forbade military sales to warring countries, it considered Canada to be neutral, thus allowing arms sales and deliveries to continue.

Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings of Ottawa, First Canadian to die in World War II, 3 September 1939. His brother, W.O.2 Kenneth Cummings, was to die piloting a bomber over enemy territory in 1944. Ottawa Citizen, 6 September 1939.At the German Consulate located in the Victoria Building on Wellington Street, it was “business as usual” though most likely the German diplomats were busy destroying confidential documents in preparation for an imminent departure. Dr. Erich Windels, the German Consul General who had been in Ottawa since 1937, had received no instructions from the Department of External Affairs to leave the country. Guards were, however, posted at the Victoria Building and at 407 Wilbrod Street in Sandy Hill, the home of Dr. and Mrs Windels, a short walk away from Laurier House, the downtown home of their friend, the Prime Minister.

Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings of Ottawa, First Canadian to die in World War II, 3 September 1939. His brother, W.O.2 Kenneth Cummings, was to die piloting a bomber over enemy territory in 1944. Ottawa Citizen, 6 September 1939.At the German Consulate located in the Victoria Building on Wellington Street, it was “business as usual” though most likely the German diplomats were busy destroying confidential documents in preparation for an imminent departure. Dr. Erich Windels, the German Consul General who had been in Ottawa since 1937, had received no instructions from the Department of External Affairs to leave the country. Guards were, however, posted at the Victoria Building and at 407 Wilbrod Street in Sandy Hill, the home of Dr. and Mrs Windels, a short walk away from Laurier House, the downtown home of their friend, the Prime Minister.

Even before Mackenzie King had spoken that evening to Canadians, Canada, and Ottawa specifically, had already sustained their first wartime casualties. Four hours after Britain’s declaration of war, RAF Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings, the son of Mr and Mrs James Cummings of 46 Spadina Avenue in Ottawa, died, along with his Scottish gunner, in an airplane accident. Based at the RAF base in Evanton, Scotland, Cummings’ Westland Wallace biplane crashed into a hillside in thick fog. Cummings was the first Canadian to die in the War. His family received the grim news the following day. Cummings, age 24, had enlisted in the RAF in 1938. He had attended Glebe Collegiate and had been a member of Parkdale United Church. His father was the superintendent of the transformer and meter department of the Ottawa Electric Company.

Just a few hours later, a German U-boat deliberately sank the SS Athenia, a 526-foot, 13,500-ton passenger liner—the first British ship lost in the war. The liner, owned by the Donaldson Atlantic Line, had left Glasgow for Montreal, with a stop in Liverpool, on 1 September, two days before the outbreak of war. On board were 1,103 passengers and 315 crew members, of whom 469 were Canadians and another 311 Americans who were trying to get back home before hostilities began. Approximately twenty-one of the Canadians either came from Ottawa or had close relatives in Ottawa. Also on board were 500 Jewish refugees as well as 72 UK residents, plus a medley of citizens from other countries. Twenty-eight German and six Austrian citizens were on the liner.

At roughly 7.30pm in the evening of 3 September, local time (2.30pm Ottawa time), the ship, located off the western coast of Scotland, two hundred miles north of Ireland, was torpedoed by U-30 under the command of Oberleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp. As the ship began to settle into the water, the submarine came to the surface and fired two shells at the stricken ocean liner. While there was ample time for the ship’s lifeboats to get away, there were many casualties, in part due to accidents during the rescue by two British destroyers, a Swedish yacht, the Southern Cross, a Norwegian tanker, the Knute Nelson, and an American freighter, the City of Flint. In total, 98 passengers and nineteen crew members died, including 54 Canadians and 28 Americans. Most survivors were brought into Glasgow in Scotland and Galway in Ireland. The City of Flint disembarked the people it had rescued in Halifax.

Fritz-Julius Lemp, commander of U-30 which sank the SS Athenia. Lemp drowned in May 1941 when his later ship U-100 was capture intact off of Iceland, its scuttling charges having failed to detonate. On board was an Enigma machine and code book which were used at Bletchley Park to decode top secret Nazi signals. U-boat.net.The sinking of the unarmed Athenia was considered a war crime as the U-boat commander had not given the passengers and crew an opportunity to leave the ship. As well, when he realized that he had fired upon a passenger liner in error, he didn’t stay to help the survivors, but instead swore his crew to secrecy. Later, fearful that the loss of American lives might bring the United States into the war, the Nazi high command ordered Lemp to falsify his log. The Nazi newspaper Volkischer Beobacher blamed the sinking on Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. While nobody believed that tale, the real story of the sinking of the Athenia wasn’t revealed until the Nuremburg trials after the war.

Fritz-Julius Lemp, commander of U-30 which sank the SS Athenia. Lemp drowned in May 1941 when his later ship U-100 was capture intact off of Iceland, its scuttling charges having failed to detonate. On board was an Enigma machine and code book which were used at Bletchley Park to decode top secret Nazi signals. U-boat.net.The sinking of the unarmed Athenia was considered a war crime as the U-boat commander had not given the passengers and crew an opportunity to leave the ship. As well, when he realized that he had fired upon a passenger liner in error, he didn’t stay to help the survivors, but instead swore his crew to secrecy. Later, fearful that the loss of American lives might bring the United States into the war, the Nazi high command ordered Lemp to falsify his log. The Nazi newspaper Volkischer Beobacher blamed the sinking on Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. While nobody believed that tale, the real story of the sinking of the Athenia wasn’t revealed until the Nuremburg trials after the war.

Over the next several days, anxious Ottawa residents repeatedly called the Citizen for any news of loved ones who had been on the Athenia. For the most part the news was positive as one by one, the rescued Ottawa people were reported safe, mostly from Glasgow and Greenock in Scotland or Galway in Ireland. These included D. George Woollcombe, the former head master of Ashbury College, Miss Jean Craik, a young business college student who resided at 471 MacLeod Street, and Miss Mary Carol of 34 Noel Street, an employee at Ogilvie’s Department Store. Mr. James Ward of the Public Works Department also received word that his wife and 12-year old son, James Jr. were safe in Galway, Ireland. Thomas Graham of 224 Primrose Street who had joined the crew of the Athenia two weeks earlier as a cook was also safe on dry land.

Jean Craik was among the first Ottawa survivors to return home. Arriving shortly before midnight on the CNR train from Halifax with two other survivors eleven days after the Athenia was torpedoed, Craik recounted a harrowing tale. She had been on deck when the ship had been torpedoed and sailors started shouting for everybody to abandon ship. On her lifeboat were 56 mostly women and children and two sailors. She sat in the stern of the lifeboat where she was given the job of holding flares. A sailor named Kammin gave her his lifebelt, an act of heroism that saved her life and lost his. In heavy seas, her lifeboat capsized. Kammin perished. Many drowned in front of her, including a mother and a baby. Craik floated in the water for six hours before the Southern Cross rescued her. Of the 56 people who made it onto the lifeboat, roughly half lost their lives through drowning. The Southern Cross transferred Craik and other survivors to the City of Flint, who took them to Halifax. There, the Red Cross gave Craik a tooth brush, tooth paste, cold cream and a pair of silk stockings. One of the first things she did in Halifax was have a hot bath. Although she had lost all her possessions, Craik somehow managed to keep her purse which she had tied to herself. In it was one traveller’s cheque which she used to buy new clothes.

All the news was not good, however. Mr. F.H. Blair of Montreal, the uncle of Miss A.E. Brown of 415 Elgin Street, lost his life. He had given his life jacket to a woman, and subsequently drowned.

Canada joined Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand and other members of the Empire in the war against Nazi Germany on 10 September. After the Parliamentary debate, Canadian High Commissioner to London, Vincent Massey, received a cable from Ottawa recommending to King George that as King of Canada he approve Canada’s declaration of war on Germany. Massey transcribed the cable’s contents onto two ordinary sheets of foolscap paper which he took to Buckingham Palace. The King appended his signature “Approved George R.I.” Canada was officially at war.

Sources:

Boswell, Randy, 2012. “Memorial unveiled to first Canadian pilot to die in WWII,” Edmonton Journal, 6 September.

Bregha, François, 2019. “Australia House,” History of Sandy Hill, https://www.ash-acs.ca/history/australia-house/.

British Home Child Group International, 2019. “The Athenia,” http://britishhomechild.com/the-athenia/.2012.

Kemble Mike, 2013. “SS Athenia,” Merchant Navy in World War II, http://www.39-45war.com/athenia.html.

Ottawa Citizen, 1939. “Most Ottawa Folk Philosophical, But Ready To Do Duty,” 1 September.

——————, 1939. “Crowds Throng Citizen Bulletins,” 1 September.

——————, 1939. “Gunners Will Move To Lansdowne Pk For Training Duty,” 2 September.

——————, 1939. “Liner Athenia, Bound For Canada, Torpedoed, Britain And France Now At War With Germany,” 4 September.

—————–, 1939. “Proclamation Declaring Great Britain At War Isued By Chamberlain,” 4 September.