Super User

Vexing Vexillology

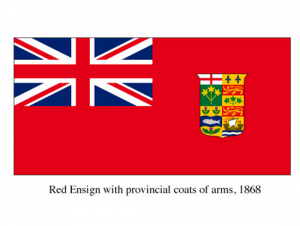

Of course, views evolved and shifted over time. During the early, uncertain years immediately after Confederation, support for the British connection was very strong, politically and emotionally. With the United States casting an avaricious eye northwards, you can appreciate this sentiment. Even Quebecers were content to live under the British flag, in a land that provided a constitutional guarantee for their religious and linguistic rights. The flag most commonly, but unofficially, flown at that time was the British Red Ensign with the provincial shields of the four founding provinces on the fly. As additional provinces joined Confederation, their arms were added.

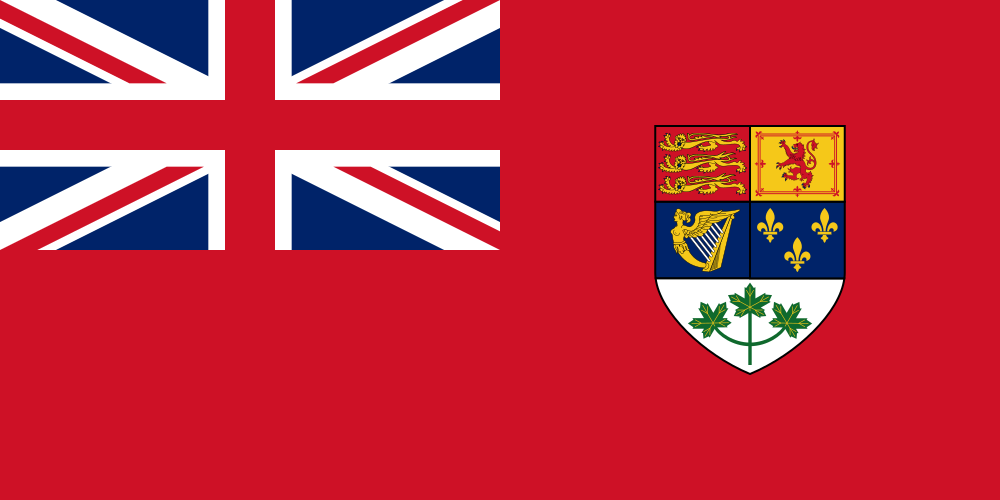

While a Red Ensign with a Canadian coat of arms on the fly was approved by the British Admiralty for use by Canadian-registered ships in 1902, at home things seemed to go backwards. The federal government began flying the Union Flag, or Jack, over Parliament Hill after the Boer War reflecting the prevailing strong imperial feelings. But nationalist sentiment surged during World War I. Although Canadian soldiers fought under the Union Flag, they were identified by a maple leaf emblem on their uniforms. With Canada coming of age on the battlefield, and amidst growing national confidence, there was heightened interest in developing a distinctive Canadian flag. In 1922, the government of Mackenzie King replaced the provincial crests on the Red Ensign with the arms of Canada. Two years later, this new Canadian Red Ensign was authorized for use abroad to help identify Canadian foreign legations. However, the Union Flag continued to fly at home.

Canadian Red Ensign used from 1922-1957. In 1957, the colour of the maple leaves was changed to red.The first flag debate started innocuously. In 1925, the Department of National Defence, noting that the Canadian Red Ensign was used on Canadian-registered ships and at overseas legations, asked for something distinctive to fly at home. King set up a committee of civil servants to come up with something. When news leaked to the press, a firestorm of opposition was ignited, especially in loyalist Ontario. Demands were made for a parliamentary resolution to confirm the Union Flag as the only official Canadian flag. Heading a minority government, King wilted under the pressure. Disbanding the flag committee, he said that there would be no change in flag unless sanctioned by Parliament.

Canadian Red Ensign used from 1922-1957. In 1957, the colour of the maple leaves was changed to red.The first flag debate started innocuously. In 1925, the Department of National Defence, noting that the Canadian Red Ensign was used on Canadian-registered ships and at overseas legations, asked for something distinctive to fly at home. King set up a committee of civil servants to come up with something. When news leaked to the press, a firestorm of opposition was ignited, especially in loyalist Ontario. Demands were made for a parliamentary resolution to confirm the Union Flag as the only official Canadian flag. Heading a minority government, King wilted under the pressure. Disbanding the flag committee, he said that there would be no change in flag unless sanctioned by Parliament.

The Statute of Westminster which effectively gave Canada its independence in 1931 spurred renewed efforts to design a national flag. World War II provided an additional fillip as Canadian servicemen abroad strongly favoured fighting under distinctive Canadian symbols. When Prime Minister King met Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt in Quebec City in 1943 to plan the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe, the Canadian Red Ensign flew proudly between Britain’s Union Flag and the American Stars and Stripes over La Citadelle. The following year, the Canadian Red Ensign was authorized for use by the Canadian Army on land. It temporarily replaced the Union Flag on the Peace Tower at Parliament Hill on Victory-in-Europe Day (8 May 1945), and became a permanent fixture there following an order-in-council on 5 September 1945.

Proposed Flag, 1946Late in 1945, King tried again to come up with a new national flag. A committee examined roughly 2,700 designs submitted by the general public, the majority of which featured some sort of maple leaf motif. But the committee, like its 1920s’ predecessor, struggled to find a compromise between nationalists and imperialists. A vocal minority demanded the Union Flag to be retained. The committee finally agreed to a modest change—the Red Ensign adorned with a gold maple leaf instead of the Canadian arms on the fly. Although it received King’s approval, it didn’t go over well among nationalists both inside and outside Quebec who wanted to eliminate all foreign symbols. With the country still divided, the flag issue returned to the back burner and left to simmer for another twenty years.

Proposed Flag, 1946Late in 1945, King tried again to come up with a new national flag. A committee examined roughly 2,700 designs submitted by the general public, the majority of which featured some sort of maple leaf motif. But the committee, like its 1920s’ predecessor, struggled to find a compromise between nationalists and imperialists. A vocal minority demanded the Union Flag to be retained. The committee finally agreed to a modest change—the Red Ensign adorned with a gold maple leaf instead of the Canadian arms on the fly. Although it received King’s approval, it didn’t go over well among nationalists both inside and outside Quebec who wanted to eliminate all foreign symbols. With the country still divided, the flag issue returned to the back burner and left to simmer for another twenty years.

The great flag debate of 1963-64 pitted Lester B. Pearson against John G. Diefenbaker. Pearson, at the head of a minority Liberal government, promised that Canada would have a new flag in time for its 1967 centennial. His point man on the flag issue was John Matheson, the Liberal MP for Leeds. Drawing on earlier maple-leaf proposals, and using the red and white colours of Canada proclaimed by King George V in 1921, he suggested a design of three red maple leaves on a white field. Matheson’s simple but striking proposal was subsequently modified by designer Allan Beddoe who added two vertical blue bars on either side to represent the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. A delighted Pearson presented this design to Parliament in June 1964.

The "Pearson Pennant," 1964

The "Pearson Pennant," 1964  Flag of Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario As in the past, the country was riven over the flag question. Diefenbaker, the old Conservative who cherished the imperial connection, fought tooth and nail against what he derisively called the “Pearson pennant.” Canadian veterans, who favoured retaining the Canadian Red Ensign, booed and hissed at Pearson when the prime minister came to address the Winnipeg Legion in May 1964. But a majority of Canadian were ready for change. A special 15-member committee, chaired by Herman Batten, was given the herculean task of finding a new flag. After gruelling discussions and the consideration of roughly 3,500 suggestions sent in by Canadians, three design archetypes made the finals: a flag containing the Union Flag or fleur-de-lys, a three-leaf flag represented by the Pearson pennant, and a one-leaf flag represented by the red and white maple leaf flag. The third design was inspired by the flag of the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario. In March 1964, Col. George Stanley, the Dean of Arts at RMC, suggested to John Matheson that the RMC’s red and white flag might make a suitable national standard if the RMC crest were replaced with a red maple leaf. With a little tweaking of the design to enlarge the white central panel to better display the single, eleven-point red maple leaf of designer Jacques St. Cyr, our flag was conceived.

Flag of Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario As in the past, the country was riven over the flag question. Diefenbaker, the old Conservative who cherished the imperial connection, fought tooth and nail against what he derisively called the “Pearson pennant.” Canadian veterans, who favoured retaining the Canadian Red Ensign, booed and hissed at Pearson when the prime minister came to address the Winnipeg Legion in May 1964. But a majority of Canadian were ready for change. A special 15-member committee, chaired by Herman Batten, was given the herculean task of finding a new flag. After gruelling discussions and the consideration of roughly 3,500 suggestions sent in by Canadians, three design archetypes made the finals: a flag containing the Union Flag or fleur-de-lys, a three-leaf flag represented by the Pearson pennant, and a one-leaf flag represented by the red and white maple leaf flag. The third design was inspired by the flag of the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario. In March 1964, Col. George Stanley, the Dean of Arts at RMC, suggested to John Matheson that the RMC’s red and white flag might make a suitable national standard if the RMC crest were replaced with a red maple leaf. With a little tweaking of the design to enlarge the white central panel to better display the single, eleven-point red maple leaf of designer Jacques St. Cyr, our flag was conceived.

When the committee came to choose among the designs, Matheson outmanoeuvred the Conservatives. On a series of votes, the Canadian red ensign was eliminated, as was any new design containing the Union Flag or fleu-de-lys. That left in contention the Prime Minister’s three-leaf flag and Col. Stanley’s one-leaf flag. Expecting the Liberals to support their leader’s cherished “pennant,” the Conservatives voted for the one-leaf flag. But Matheson, realizing that Pearson’s choice was a non-starter, had already solicited the other members’ support for the one-leaf design. When the secret ballots were tallied on 22 October 1964, Conservative members were horrified to discover that it was a unanimous committee decision for the red and white, single-leaf flag.

The Maple Leaf flag flies for the first time, 15 February 1965The kicking and screaming continued in the House of Commons for the next two months but this time the end was in sight. After closure was applied to limit debate, weary MPs voted 163-78 for the single-leaf design at 2:00am on 15 December 1964. Two days later the Senate passed the necessary legislation, and on 24 December Queen Elizabeth gave her approval. A Royal Proclamation, describing Canada’s new flag in appropriate heraldic terms, was released on 28 January 1965.

The Maple Leaf flag flies for the first time, 15 February 1965The kicking and screaming continued in the House of Commons for the next two months but this time the end was in sight. After closure was applied to limit debate, weary MPs voted 163-78 for the single-leaf design at 2:00am on 15 December 1964. Two days later the Senate passed the necessary legislation, and on 24 December Queen Elizabeth gave her approval. A Royal Proclamation, describing Canada’s new flag in appropriate heraldic terms, was released on 28 January 1965.

At noon, on 15 February 1965, in front of a crowd of 10,000 on Parliament Hill and in the presence of the Governor General, Georges Vanier, Prime Minister Pearson, and an unhappy Diefenbaker, RCMP constable Gaetan Secours lowered the old Canadian Red Ensign for the last time and raised Canada’s new national standard. As the Governor General’s flag was flying on top of the Peace Tower as protocol demanded, our new national flag was raised on a temporary flagstaff set up specially for the occasion. When it reached the top of the pole, a timely puff of wind unfurled our now much-beloved, red and white, Maple Leaf Flag for all to see. Canada’s official national flag was born.

Sources:

Archbold, Rick, 2014. A Flag for Canada.

Canada Heritage, 2014. Birth of the National Flag of Canada.

CBC, 2001. The Great Flag Debate.

Fraser, Alistair B., 1998. The Flags of Canada.

Le Citoyen, 1964. “Enfin! Un drapeau canadien,” 16 décembre.

The Globe and Mail, 1964. “Pearson Booed, Hissed Over Maple Leaf Flag,” 18 May.

——————–, 1965. “Pearson’s Address on the Maple Leaf Flag,” 16 February.

——————–, 1965, “PM Proclaims a New Era as Leaf Replaces Ensign,” 16 February.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1945. “Warm Debate In House On Contentious Canadian Flag Issue,” 9 November.

Le Salaberry, 1959. “Un drapeau canadien,” 22 janvier.

The Maple Leaf, 1945. “Canadian Flag,” 7 July 1945.

Yukon World, 1904. “The Canadian Flag,” 17 September.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Bank of Ottawa

20 January 1919

Toronto has its Toronto-Dominion Bank. Montreal has its Bank of Montreal. One hundred years ago, Ottawa had its own Bank of Ottawa too. Of the nineteen Canadian chartered banks at the end of 1918, the Bank of Ottawa ranked in the middle of the pack. Its assets stood at $72.7 million, with paid-in capital and reserves of $8.75 million. In comparison, the Bank of Montreal, Canada’s financial goliath at the time, had assets of $558 million and paid-in capital and reserves of $32 million. Still, the Bank of Ottawa was a well-respected regional bank whose main area of operations were located in the City of Ottawa and in the Ottawa Valley on both sides of the river. One of its directors, Sir George Burn, who had previously been its general manager for most of the bank’s existence, was also president of the prestigious Canadian Bankers’ Association.

The Bank of Ottawa commenced operations at the beginning of December in 1874 with its head office in the Victoria Chambers at the corner of Wellington and O’Connor Streets across from Parliament Hill. (The location is now the site of the Victoria Building, constructed in 1928.) The new bank had one branch located in Arnprior. Oddly, the Arnprior branch began operations roughly two weeks before the main branch as the bank’s headquarters were not ready on opening day.

The Bank of Ottawa was started by a number of the area’s lumber barons with the express purpose of having a sympathetic financial institution in the region to fund the lumber industry. Widely known as the “lumberman’s bank,” its first president was James Maclaren, a lumberman from Buckingham, Quebec. Other directors included George Bryson, a lumberman who operated out of Fort Coulonge, Quebec, Robert Blackburn, owner of the Hawkesbury Lumber Company, and Allan Gilmour, a pioneering Bytown lumberman who owned one of the largest timber companies in Canada. Other directors, all prominent Ottawa businessmen and suppliers to the timber trade, included Charles Magee, an important wholesale dry goods merchant, C. T. Bate, a wholesale grocer, and George Hay who owned a hardware business. The Bank of Ottawa’s initial paid-in capital was $343,000, and had thirteen employees. After its first year in business, the bank paid a dividend of 7 per cent.

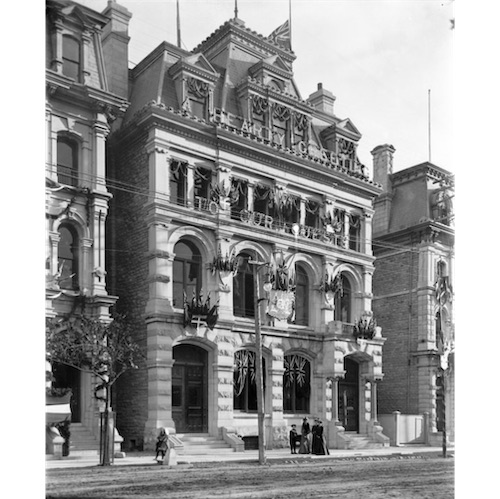

Bank of Ottawa, Head Office, Wellington Street, 1901. Decorated for the Royal Visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, the future King George V and Queen Mary

Bank of Ottawa, Head Office, Wellington Street, 1901. Decorated for the Royal Visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York, the future King George V and Queen Mary

William James Topley / Library and Archives CanadaGiven the costs of starting a new enterprise, and the weak state of the Canadian economy during the mid-1870s, the profits of the new enterprise might not have justified such a dividend. Indeed, the bank temporarily cut its dividend in half. However, the new financial institution gradually expanded, building itself a profitable niche in eastern Ontario and western Quebec. By 1885, ten years after it started, the bank had a paid-in capital of $1 million, with a steadily expanding branch network in the Ottawa Valley. It opened its second and third branches in Carleton Place and Pembroke. Over time, it increased its annual dividend to 12 per cent (of paid-in capital).

Its first branch outside of the region was in Winnipeg in 1881. As this was before the opening of the trans-continental Canadian Pacific Railway, the bank had difficulties in transporting a large safe to the branch. After being told by the Grand Trunk Railway that it would take up to six weeks to deliver it to Winnipeg, the Toronto, Grey & Bruce Railway agreed to do it in fifteen days via trains to Minneapolis, Minnesota, and then to Emerson, Manitoba, with the last leg to Winnipeg via boat on the Red River. The Bank of Ottawa subsequently opened offices in Toronto and Montreal, Canada’s two financial centres at the time, as well as Vancouver. In 1884, it moved into its new head office building on Wellington Street a short distance from its original offices. (The site is approximately the vacant lot between the former U.S. Embassy building and the former Union Bank building at 128 Wellington Street.)

The salad years for the institution occurred between 1908 and 1913, when the bank experienced rapid growth, with its paid-in capital rising to $4 million. By the end of World War I, the bank had 96 branches, with more than 60 in Ontario and another thirteen in the province of Quebec, mostly in the Outaouais.

Given its years of service and key position in Ottawa economic and financial life, imagine the shock in Ottawa and the Valley when the bank’s directors, many of whom were the sons of the Bank’s founders, announced on 20 January 1919 that they had agreed to merge with the Bank of Nova Scotia. The Bank of Nova Scotia, with its head office in Toronto, was roughly twice the size of the Bank of Ottawa with assets of $149 million in 1918 with capital, reserves of about $18.5 million. It had 194 branches coast to coast. It was a friendly take-over. Apparently, the Bank of Nova Scotia approached the Bank of Ottawa. Under the terms of the deal, shareholders of the Bank of Ottawa received four Bank of Nova Scotia shares for every five shares of the Bank of Ottawa. This was the ratio of their share prices prior to the deal; Bank of Nova Scotia shares were trading at $257 per share on the Montreal Stock Exchange while Bank of Ottawa shares traded at $206.

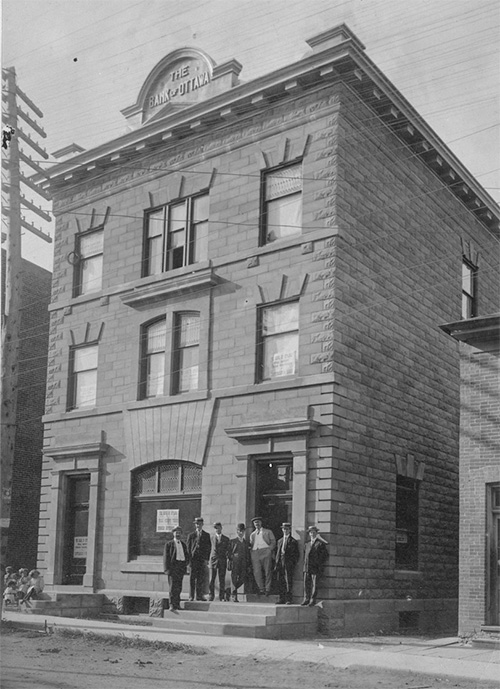

Bank of Ottawa, Kemptville Branch

Bank of Ottawa, Kemptville Branch

Department of Public Works / Library and Archives Canada, PA-046461The deal had advantages for both banks. For the Bank of Nova Scotia, the merger brought it a thriving business with a solid reputation in areas where it had few branches, both in the Ottawa region as well as in western Canada where the institution was eager to expand. The two banks had competing offices in only eleven locations, most of which were in major cities where there was more than enough business to go around. The merger would also raise the Bank of Nova Scotia to fourth place in the Canadian bank rankings, behind only the Bank of Montreal, the Royal Bank of Canada, and the Bank of Commerce.

For the directors of the Bank of Ottawa, who had brushed off earlier overtures by other banks, an alliance with the Bank of Nova Scotia offered “exceptional advantages.” The merger was a way of entering new more profitable areas at less expense. Alone, the bank had a choice of trying to expand organically in the Ottawa region, or through the expensive route of establishing new branches in unfamiliar areas. But by joining the Bank of Nova Scotia, it could take advantage of the growth potential of a bank that had branches across Canada, Newfoundland, the West Indies as well as operations in the United States. The Bank of Nova Scotia was also better diversified, reducing the consequences of an economic slowdown in the Ottawa region. This was an astute move as Canada experienced a sharp recession in the immediate post-war years.

Despite the many attractions of an alliance, there was one thorny issue to resolve—the name of the new institution. The directors of the Bank of Ottawa were loath to see the venerable name of their institution disappear. The Ottawa Evening Journal reported that for forty-four years, the Bank of Ottawa’s name was “identified with practically all of the best businesses and biggest industrial enterprises in central Canada.” At the same time, the directors of the Bank of Nova Scotia were equally unwilling to see the end of their bank’s storied name that extended back to 1832. For a time, consideration was given to calling the merged bank “The First National Bank of Canada.” However, in light of the Bank of Nova Scotia’s considerable foreign connections, the Bank of Ottawa’s directors reluctantly concluded that it would be a mistake to change names; a view shared by Sir William White, the Minister of Finance, who gave his blessing to the merger.

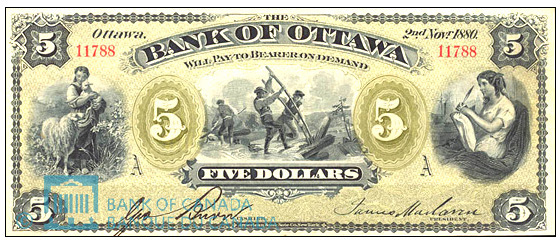

Bank of Ottawa, $5.00 note, November 1880, hand-signed by James Mclaren, President and George Burn, Cashier. Note the lumberjacks in the central vignette

Bank of Ottawa, $5.00 note, November 1880, hand-signed by James Mclaren, President and George Burn, Cashier. Note the lumberjacks in the central vignette

Bank of Canada Museum.Without any forewarning of the pending financial nuptials, the announcement of the merger created a sensation in Canadian financial circles. In Ottawa, there was consternation, especially when it became known that the Bank of Ottawa name was to disappear. One businessman, Mr. N. Poulin, said it was a “murder” not a merger. Another called it a “submerger.” Some worried about their access to credit; the Bank of Ottawa had an uncommonly good reputation for being considerate and liberal in its business decisions. One businessman was concerned that after years of dealing with the Bank of Ottawa he would have to start afresh with the Bank of Nova Scotia. Many regarded the bank as an important city asset. Its loss would be a major blow to the prestige to the nation’s capital.

The disappearance of the Bank of Ottawa name would also mean the withdrawal of almost $7 million in Bank of Ottawa banknotes from circulation and their replacement by Bank of Nova Scotia notes. Prior to the formation of the Bank of Canada in 1935, every chartered bank had the right to issue their own distinctive banknotes in the amount of its paid-in capital and reserves. While the circulation of bank notes did not represent a large portion of a bank’s business, it was quite profitable. (A bank earned the difference between the cost of printing and circulating its banknotes, and the interest earned on the assets backing the notes.) It also provided useful advertising for the bank, and in the case of the Bank of Ottawa, for the city as well. Mr Poulin commented that “with a roll of Bank of Ottawa ten dollar bills in his pocket a man could go to any part of the world and feel comfortable and safe.”

At a hastily-called meeting of Ottawa retail merchants, a resolution was passed citing the merchants’ belief that the departure of the head offices of Ottawa’s only financial institution would have “a decidedly bad effect” on the city. More broadly, they were concerned that the concentration of more financial power and decision-making in Toronto and Montreal would be bad for the country. (There had been a rash of financial takeovers, including the acquisition of the Traders Bank of Canada, the Quebec Bank and the Northern Crown Bank by the Royal Bank of Canada, as well as the acquisition of the Bank of British North America by the Bank of Montreal.) Some thought that a committee should be struck to approach the directors of the Bank of Ottawa to get a better understanding of their decision. Some even pledged money to buy shares in the bank in an effort to stop the merger. Still others wanted to approach the Finance Minister to get him to reverse his decision to permit the merger. They noted that an attempt by the Royal Bank of Canada to acquire the Bank of Hamilton a few years earlier had been stopped by the Minister on the grounds that the merger was against the national interest. Mr A. E. Corrigan, the managing director of the Capital Life Assurance Company likened a bank to a “public utility” that had been given a franchise to serve the people. Consequently, the people had a right to protest if a merger was not in their interest. One person alleged that the reason why the Finance Minister approved the merger was because the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, was a shareholder in the Bank of Nova Scotia.

The general manager of the Bank of Ottawa, Mr. D. M. Finnie, tried to allay people’s concerns. He noted that while he would be retiring following the merger, all Bank of Ottawa staff would be retained with the same seniority and opportunities. Critically for Bank of Ottawa customers, its directors would retain their positions within the amalgamated bank and would pay special attention to former Bank of Ottawa clients. Bank of Ottawa customers would also have complete access to the Bank of Nova Scotia’s branches across the country.

At special shareholder meetings held in early March, the shareholders of the Bank of Ottawa and the Bank of Nova Scotia overwhelmingly approved the merger. Following the declaration of a last dividend (no. 111) of 2 per cent for the two-month period ending 30 April 1919, the Bank of Ottawa disappeared into history with all of its assets and liabilities transferred to the Bank of Nova Scotia as of that day. The next morning, all branches of the Bank of Ottawa re-opened as branches of the Bank of Nova Scotia.

Sources:

Globe (The), 1919. “Bank of Ottawa Absorbed by Bank of Nova Scotia,” 20 January.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1918. “Bank of Ottawa’s Gratifying Year,” 19 December.

————————————-, 1919, “Bank of Ottawa To Be Merger With Bank Of Nova Scotia, Making Fourth Largest Bank,” 20 January.

————————————-, 1919. “Says The Merger Will Result In Advantage To All Canada,” 20 January.

————————————-, 1919. “Evolution Of A Great Bank,” 20 January.

————————————-, 1919. “The Merging Of The Bank Of Ottawa,” 20 January.

————————————-, 1919. “Bank of Ottawa Swallowed Up, Strong Protest,” 20 January.

————————————-, 1919. “Bank of Nova Scotia Stronger Than Ever,” 20 January.

————————————-, 1919. “Strong Opposition To Banks’ Merger From Businessmen,” 21 January.

————————————-, 1919. “Mr. Finnie Tells About The Merger,” 21 January.

————————————, 1919. “Great War Veterans Debate Merger Of Banks Of Ottawa And Nova Scotia At Forum, 25 January.

————————————, 1919. “Bank Of Ottawa Now Disappears,” 30 April.

————————————, 1951. “Bank of Ottawa Developed Lumber Trade,” 31 October.

Outaouais’s Forest History, 2017, “The Bank of Ottawa and the financing of the forest industry,”.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Colonel By Memorials

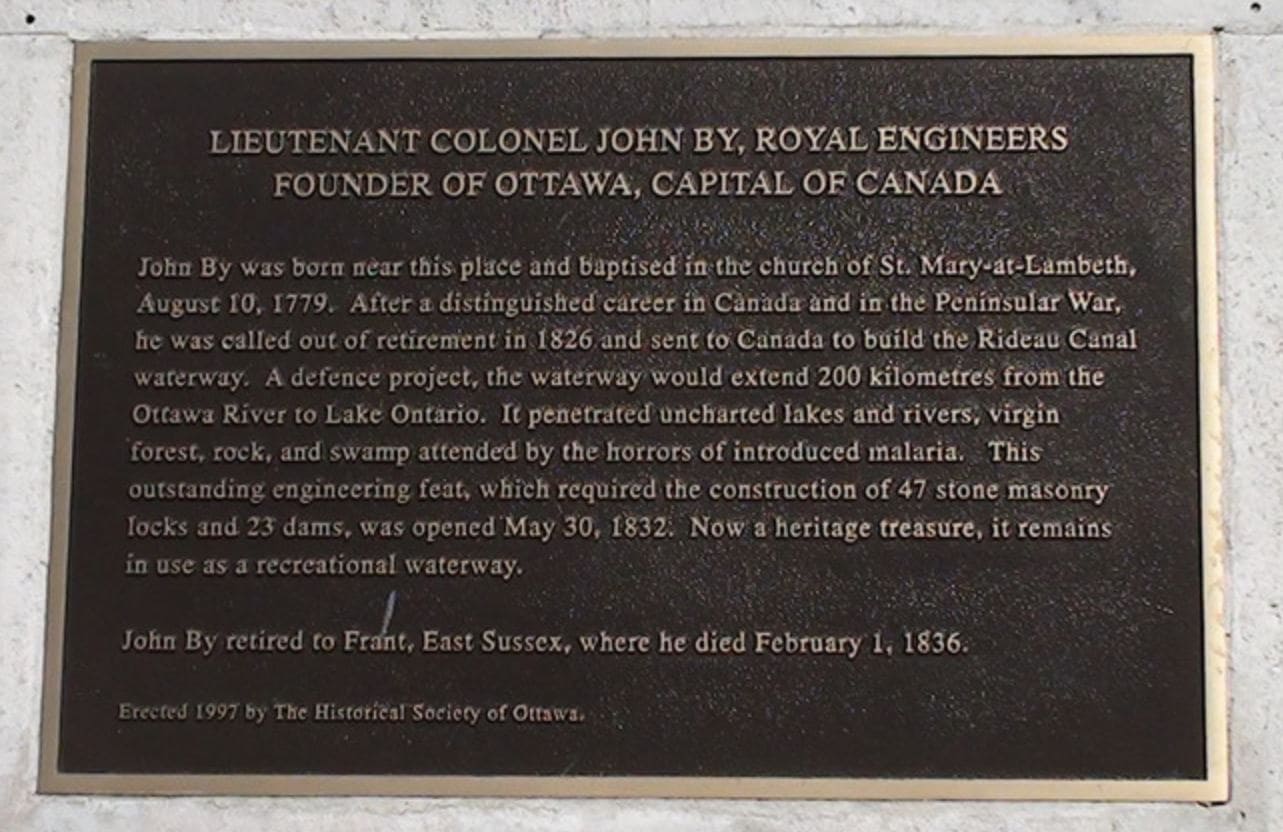

Plaque erected by the Historical Society of Ottawa in honour of Col. John By, founder of Bytown, later known as Ottawa. Photo by John Knight.The body of Lieutenant-Colonel John By, Royal Engineers, 1779-1836, is buried in St Alban’s Anglican Church in Frant, Sussex, England. Col. By supervised the building the Rideau Canal, and founded Bytown in 1826. In 1855, Bytown was renamed Ottawa. Two years later, Ottawa was selected by Queen Victoria to be the capital of the Province of Canada consisting of Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec). With the Confederation of the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia on 1 July 1867, Ottawa became the capital of the Dominion of Canada.

Plaque erected by the Historical Society of Ottawa in honour of Col. John By, founder of Bytown, later known as Ottawa. Photo by John Knight.The body of Lieutenant-Colonel John By, Royal Engineers, 1779-1836, is buried in St Alban’s Anglican Church in Frant, Sussex, England. Col. By supervised the building the Rideau Canal, and founded Bytown in 1826. In 1855, Bytown was renamed Ottawa. Two years later, Ottawa was selected by Queen Victoria to be the capital of the Province of Canada consisting of Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec). With the Confederation of the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia on 1 July 1867, Ottawa became the capital of the Dominion of Canada.

For many years, the Historical Society of Ottawa has provided funds for the maintenance of Colonel By’s resting place and memorial. For those wishing to visit St Alban’s, please consult the Church’s website.

Image courtesy of LondonRemembers.com — see more about the John By memorial on the London Remembers website In 1997, the Historical Society of Ottawa erected a plaque in honour of Colonel By on the Albert Embankment in London near St Mary-at-Lambeth Church where he was baptized in 1779. Deconsecrated in 1972, St Mary-at-Lambeth is the home of The Garden Museum and is located next to Lambeth Palace, the London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Image courtesy of LondonRemembers.com — see more about the John By memorial on the London Remembers website In 1997, the Historical Society of Ottawa erected a plaque in honour of Colonel By on the Albert Embankment in London near St Mary-at-Lambeth Church where he was baptized in 1779. Deconsecrated in 1972, St Mary-at-Lambeth is the home of The Garden Museum and is located next to Lambeth Palace, the London home of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Publications Policy

The Society shall publish reports in its Bytown Pamphlet Series on research which meets the Society’s objectives, and is either required of students under awards supported by the Society, or unsolicited from members or non-members, subject to passing an editorial review process approved by majority vote of the Board and to priorities dictated by the Society’s objectives and resources.

One copy of each report shall be distributed to each member in good standing as of its date of publication; others may buy copies at a price to be determined by a majority vote of the Board. Two copies of each published Bytown Pamphlet shall be sent to Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Ontario for legal deposit and registration under ISBN and ISSN. Two copies shall be deposited in the Historical Society of Ottawa holdings at the City of Ottawa Archives.

All manuscripts should be submitted to the Director for Publications or the Publications Committee. In accordance with the Copyright Act (R.S.C. 1970, c C-30, s.5), ownership of this intellectual material remains with the author for life plus 50 years, unless signed away to someone else. HSO published formats are copyright of the HSO and shall only be reproduced with the consent of the Director for Publications or the Publications Committee. A copyright release, as follows and also available from the Publications Committee, shall also require authors to assume responsibilities to verify the copyright status of quotations and illustrations which they have provided for use in their reports, and to ensure appropriate citation of sources.

For inquiries regarding publications, please email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Copyright Release

The Historical Society of Ottawa

Publications Committee

The Historical Society of Ottawa,

Postal Box 523, Station B, Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5P6

E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Contributor’s Certification

Manuscript Title ________________________________________________________

Publication Title ________________________________________________________

I certify that:

I have acquired permission to reproduce any previously copyrighted material which I have provided for use in my manuscript including, inter alia , sources, quotations and illustrations for which I have given accurate citation in the manuscript;

I agree to transfer to The Historical Society of Ottawa (HSO) publishing rights to the manuscript: that is, without relinquishing my proprietary rights as author, I transfer to HSO the rights to reproduce and distribute the article in HSO format, including figures and graphic reproductions, and the right to adapt the manuscript to conform to HSO publishing standards; and

(Please strike out one):

I agree that the article may be reprinted or copied for non-profit use by individuals and organizations without my written permission, providing proper credit is given to the source of the item

or

I require that the article should be accompanied by the copyright symbol (©) denoting that

the article may not be printed or copied without my written permission.

Signature: ____________________________________

Printed Name: ____________________________________

Date: _______________________

Personal Information Protection Policy and Guiding Principles

The Historical Society of Ottawa is hereafter referred to as HSO.

HSO is committed to respecting the privacy of its members and their families by adhering to the privacy principles set forth in Schedule 1 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act. Those principles are:

Principle 1. Accountability

The Board is accountable for compliance with this policy. The President is responsible for the management of the policy, including the guiding principles. The President can be contacted at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Principle 2. Identifying Purposes

HSO only collects personal information necessary to provide a volunteer program and to meet the individual development needs of each member. Name, address and other contact information concerning membership and event registration form a permanent record for members. All other information is kept only as long as required to fulfill the purposes identified, unless permission is obtained from the individual providing the information.

Principle 3. Consent

All members and non-members will have the ability to consent to the uses of their personal information. A person grants, through the act of registering for membership or other events, consent to the use of personal information by Board members and those HSO members designated by the Board, for the purposes of providing members with HSO publications, informing members of HSO activities, and for analysis. Signing membership or registration forms or registering online will be considered consent. HSO will assume consent is granted unless a member indicates otherwise.

Principle 4. Limiting Collection

HSO will explain the purpose for collecting each piece of personal information. If it is necessary to use the personal information collected for a purpose not identified when the information was collected, consent for the new use will be obtained from members.

Principle 5. Limiting Use, Disclosure and Retention

HSO will use the personal information obtained from members and non-members only for the purposes for which it was collected, and will not disclose the information for other purposes except as noted in Principle 3, Consent, or as required by applicable law. All personal information provided to HSO will be maintained in a secure manner to ensure that its use is limited to the purposes for which it was collected. Name, address and information concerning membership and or registration will be retained by HSO permanently. Other personal information will be retained by HSO for whatever periods are required by legislation governing our operation and/or the information provided, after which time the information will be destroyed in a secure manner (unless consent is given to keep information for a longer period). If there is no legislative requirement to retain other information it will be kept for 24 months from the time it was provided.

Principle 6. Accuracy

Members will have the ability to view and review data provided on their application for membership at any time. Individuals may on presentation of a document establishing their identity to the President, be able to find out whether personal information is on file with HSO, and if so consult it free of charge. A request may also be made in writing or by telephone to view information. A charge may apply for the transcription, reproduction, or transmission of the information.

Principle 7. Safeguards

HSO will assess and implement appropriate measures to properly protect personal data. These measures will be subject to independent audit to ensure their effectiveness.

Principle 8. Openness

This policy and the following processes and procedures for obtaining access to personal information will be available to any individual through the HSO web site, and in the compilation of HSO bylaws, policies and procedures. If any individual has a question regarding personal information, it may be directed to the President at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Principle 9. Individual Access

Individuals will have access to their personal information provided on the application for membership at any time. On request to the President, an individual will be informed of the existence, use and any disclosure of their personal information, and will be given access to view that information. An individual may challenge the accuracy and completeness of the information, and have it corrected or amended as appropriate.

Principle 10. Challenging Compliance

Individuals may challenge the compliance of HSO with this policy by contacting the President. Procedures will be established to deal with an individual’s concern in an appropriate and timely fashion.

Definitions:

- Member: an individual that has completed an application for membership, has been accepted for membership , has paid the annual membership fee for the current year and has been granted a membership for a current one-year period or holds a Life membership;

- Non-Member: an individual who attends or registers for an event or activity sponsored by HSO but is not a member;

- Individual: refers to a member or non-member.

Governance of Motions and Debate

A motion is a proposal that the entire membership take action or a stand on an issue. An Individual Member can:

- Propose a Motion;

- Second Motions;

- Debate motions;

- Vote on motions.

There are four Basic Types of Motions:

- Main Motions: The purpose of a main motion is to introduce items to the membership for their consideration. They cannot be made when any other motion is on the floor, and yield to privileged, subsidiary, and incidental motions;

- Subsidiary Motions: Their purpose is to change or affect how a main motion is handled, and is voted on before a main motion;

- Privileged Motions: Their purpose is to bring up items that are urgent about special or important matters unrelated to pending business;

- Incidental Motions: Their purpose is to provide a means of questioning procedure concerning other motions and must be considered before the other motion.

Presentation of a Motion

- Obtaining the floor:

- Wait until the last speaker has finished;

- Wait until the Chairman recognizes you;

- Rise and address the Chairman by saying, "Mr. Chairman, or Mr. President."

- Make Your Motion:

- Speak in a clear and concise manner;

- Always state a motion affirmatively. Say, "I move that we ..." rather than, "I move that we do not ...";

- Avoid personalities and stay on your subject.

- Wait for Someone to Second Your Motion:

- Another member will second your motion or the Chairman will call for a second:

- If there is no second to your motion it is lost.

- The Chairman States Your Motion:

- The Chairman will say, "it has been moved and seconded that we ..." Thus placing your motion before the membership for consideration and action;

- The membership then either debates your motion, or may move directly to a vote;

- Once your motion is presented to the membership by the chairman it becomes "assembly property", and cannot be changed by you without the consent of the members.

- Expanding on Your Motion:

- The time for you to speak in favor of your motion is at this point in time, rather than at the time you present it;

- The mover is always allowed to speak first;

- All comments and debate must be directed to the chairman;

- Keep to the time limit for speaking that has been established;

- The mover may speak again only after other speakers are finished, unless called upon by the Chairman.

- Putting the Question to the Membership:

- The Chairman asks, "Are you ready to vote on the question?";

- If there is no more discussion, a vote is taken;

- On a motion to move the previous question may be adapted.

Voting Policy

This Voting Policy applies to all HSO formally constituted meetings of the Membership and of the Board.

When the Chair calls for a vote, abstentions shall not be called for since an abstention is meaningless. "To 'abstain' means not to vote at all." (Robert's Rules, 11th ed., p 45). Unless there is good reason not to vote, all present should vote on all resolutions.

Notwithstanding that it is the duty of every eligible voter who has an opinion on a question to express it by a vote; the individual can abstain, since voting cannot be compelled. (Robert's Rules, 11th ed., p 407).

Remaining Silent.

The burden is on an abstaining individual to speak up in order to be recorded as an abstention. If the vote is called for and any individual fails or refuses to indicate "yes," "no" or "abstain," the Chair of the meeting shall deem the individual to have voted a " silent yes" and if the silent individual does not object, the vote shall be counted as a "yes" vote.

A block of recorded abstentions cannot defeat a resolution as a recorded abstention is not a vote unless, reductio ad absurdum, all eligible voters record their abstention.

Application to HSO Votes

- For an Ordinary (Majority) Resolution, if 51% of the eligible votes* cast are “yes” including “silent yes” votes, the motion is carried.

- For a Special Resolution, if 67% of the eligible votes* cast are “yes” including “silent yes” votes, the motion is carried.

- For an Extraordinary Resolution (including to approve the conduct of a Review Engagement), if 80% of the eligible votes cast* are “yes” including “silent yes” votes, the motion is carried.

- For a Unanimous Vote ( required of the Board to discipline a Member) , a recorded abstention shall defeat the motion

* This includes the Chairman’s privilege to cast a second vote in the event of a tied vote.

Required Abstentions for Directors

- Whenever a Director believes he/she has a conflict of interest, that Director shall abstain from voting on the issue and make sure the abstention is noted in the minutes. (Robert's Rules, 11th ed., p 407).

- A Director shall abstain when he/she believes that there is insufficient information to make a decision and make sure the abstention is noted in the minutes.

- A Director shall abstain when a motion directly affects his/her position, nomination or personal benefit and make sure the abstention is noted in the minutes.

- Unless the above clauses 1, 2, or 3 are invoked, a Director shall cast votes on all issues put before the Board. Failure to do so could be deemed a breach of fiduciary duties.

The Historical Society of Ottawa Constitution and By-Law#1

UPDATED at the 2024 Annual General Meeting held June 11, 2025:

The constitution of the Historical Society of Ottawa: The Historical Society of Ottawa Constitution and By-Law#1 (PDF document)

Our History

(Drawn from Mullington, Dave, 2013. “To Be Continued…A Short History of the Historical Society of Ottawa,” HSO Publication No. 88.)

Lady Matilda Edgar, née Ridout, (1844-1910), wife of Sir James Edgar, Speaker of the House of Commons, chaired the inaugural meeting of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archive Canada, PA-025868On June 3, 1898, thirty-one Ottawa women, united by a desire to preserve and conserve Canada’s historical heritage, assembled in the drawing room of the Speaker of the House of Commons located in the old Centre Block on Parliament Hill. Chairing the meeting was the prominent author and early feminist Lady Matilda Edgar (née Ridout) wife of Sir James Edgar, the Speaker. The cream of Ottawa society attended the meeting, including Lady Zoë Laurier, the wife of the then Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Mrs Adeline Foster, the wife of the prominent Conservative politician Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, and Mrs Margaret Ahearn, the spouse of Mr Thomas Ahearn, the famous Ottawa-born inventor and businessman. The ladies agreed to form the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. As reported by the Ottawa Journal, they hoped “to resurrect from oblivion things of interest to every patriot Canadian woman, and preserve such things that are already treasures.”

Lady Matilda Edgar, née Ridout, (1844-1910), wife of Sir James Edgar, Speaker of the House of Commons, chaired the inaugural meeting of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archive Canada, PA-025868On June 3, 1898, thirty-one Ottawa women, united by a desire to preserve and conserve Canada’s historical heritage, assembled in the drawing room of the Speaker of the House of Commons located in the old Centre Block on Parliament Hill. Chairing the meeting was the prominent author and early feminist Lady Matilda Edgar (née Ridout) wife of Sir James Edgar, the Speaker. The cream of Ottawa society attended the meeting, including Lady Zoë Laurier, the wife of the then Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Mrs Adeline Foster, the wife of the prominent Conservative politician Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, and Mrs Margaret Ahearn, the spouse of Mr Thomas Ahearn, the famous Ottawa-born inventor and businessman. The ladies agreed to form the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. As reported by the Ottawa Journal, they hoped “to resurrect from oblivion things of interest to every patriot Canadian woman, and preserve such things that are already treasures.”

Under its original 1898 Constitution, the objective of the Society was to encourage “the study of Canadian History and Literature, the collection and preservation of Canadian historical records and relics, and the fostering of Canadian loyalty and patriotism.” The Constitution also stressed that “neither political parties nor religious denominations” would be recognized. Adeline Foster was elected as the Society’s first president. Lady Aberdeen (née Ishbel Maria Marjoribanks), the wife of the Governor General, consented to be the Society’s patron, thereby establishing a link to Rideau Hall that continues to this very day. The annual membership fee was set at fifty cents. Initially, the Society was a women-only organization, though men sometimes participated as honorary members. This situation continued until 1955, when men were allowed to join the Society as full members.

Lady Zoé Laurier, née Lafontaine, (1841-1921), wife of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada, was a founding member of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archives Canada, PA-028100During the early years of the Society’s history, particular attention was paid to the collection and preservation of important artifacts and historical documents. The Society put on its first exhibition of historical objects in 1899. This collection, which was to expand greatly over the coming decades, went on permanent display with the opening in 1917 of the Bytown Historical Museum, located in the old Registry Office on Nicholas Street. The museum was staffed and operated by Society volunteers. Other activities included regular lectures and the publication of historical research. The Society was also instrumental in the erection of the statue of the French explorer Samuel de Champlain at Nepean Point in 1915. To celebrate Ottawa’s centenary in 1926, the Society unveiled a memorial to Lieutenant-Colonel John By, the Royal Engineer responsible for the construction of the Rideau Canal, and the founder of Bytown. A replica of his house, which had been destroyed by fire years earlier, was also built at Major’s Hill Park.

Lady Zoé Laurier, née Lafontaine, (1841-1921), wife of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada, was a founding member of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898. Library and Archives Canada, PA-028100During the early years of the Society’s history, particular attention was paid to the collection and preservation of important artifacts and historical documents. The Society put on its first exhibition of historical objects in 1899. This collection, which was to expand greatly over the coming decades, went on permanent display with the opening in 1917 of the Bytown Historical Museum, located in the old Registry Office on Nicholas Street. The museum was staffed and operated by Society volunteers. Other activities included regular lectures and the publication of historical research. The Society was also instrumental in the erection of the statue of the French explorer Samuel de Champlain at Nepean Point in 1915. To celebrate Ottawa’s centenary in 1926, the Society unveiled a memorial to Lieutenant-Colonel John By, the Royal Engineer responsible for the construction of the Rideau Canal, and the founder of Bytown. A replica of his house, which had been destroyed by fire years earlier, was also built at Major’s Hill Park.

Mrs Adeline Foster, née Chisholm, (1844-1919), wife of Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, Conservative politician, first president of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada, Mikan No. 3423435During the lean years of the Great Depression, the Society was forced to tailor its activities to suit the straitened financial circumstances. Its publications were cut back, and a ten cent fee began to be charged for museum entry. In 1930, the annual membership fee was also increased to one dollar. Notwithstanding the difficult economic situation, the Society continued to flourish. Its collection of historical artifacts and books expanded. Meetings, historical outings, and presentations were held regularly. In 1937, the Society was officially incorporated by the Province of Ontario. With the outbreak of World War II, Society activity slowed to allow members more time to support the war effort. The museum was closed for the duration. Nonetheless, membership meetings continued to be held, and the Society’s collection of antiquities grew through donation. Members also raised money for deserving wartime causes.

Mrs Adeline Foster, née Chisholm, (1844-1919), wife of Mr (later Sir) George Eulas Foster, Conservative politician, first president of the Women's Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa. Library and Archives Canada, Mikan No. 3423435During the lean years of the Great Depression, the Society was forced to tailor its activities to suit the straitened financial circumstances. Its publications were cut back, and a ten cent fee began to be charged for museum entry. In 1930, the annual membership fee was also increased to one dollar. Notwithstanding the difficult economic situation, the Society continued to flourish. Its collection of historical artifacts and books expanded. Meetings, historical outings, and presentations were held regularly. In 1937, the Society was officially incorporated by the Province of Ontario. With the outbreak of World War II, Society activity slowed to allow members more time to support the war effort. The museum was closed for the duration. Nonetheless, membership meetings continued to be held, and the Society’s collection of antiquities grew through donation. Members also raised money for deserving wartime causes.

The Bytown Museum, formerly the Commissariat building, was built in 1827 and is the oldest stone building in OttawaFollowing the conclusion of the war, Society activities picked up. Particular attention was paid to finding a new home for the organization’s growing collection of historical artifacts and books; the old Registry Building was no longer adequate. In 1951, the Society leased premises from the federal government for a nominal fee in the Commissariat building adjacent to the Rideau Canal locks. The building, the oldest stone structure in Ottawa, was built by Scottish stonemasons hired by Colonel By during the construction of the Rideau Canal during the 1820s. Unfortunately, it was in a poor state of repairs; the building’s restoration and renovation occupied a considerable portion of the Society’s time, effort, and resources over coming years.

The Bytown Museum, formerly the Commissariat building, was built in 1827 and is the oldest stone building in OttawaFollowing the conclusion of the war, Society activities picked up. Particular attention was paid to finding a new home for the organization’s growing collection of historical artifacts and books; the old Registry Building was no longer adequate. In 1951, the Society leased premises from the federal government for a nominal fee in the Commissariat building adjacent to the Rideau Canal locks. The building, the oldest stone structure in Ottawa, was built by Scottish stonemasons hired by Colonel By during the construction of the Rideau Canal during the 1820s. Unfortunately, it was in a poor state of repairs; the building’s restoration and renovation occupied a considerable portion of the Society’s time, effort, and resources over coming years.

In 1955, there was a dramatic shift in the life of the Society. After vigorous debate, men were permitted to become full members of the Society in order to build a broader and stronger organization. The following year, the Society’s new name—the Historical Society of Ottawa—was officially adopted to reflect that change. Mr H. Townley Douglas, who had been previously active as an honorary member was elected as the Society’s first male director.

In Major's Hill Park stands the statue of Col. John By, Royal Engineers, who was responsible for building the Rideau Canal and the founding of Bytown, later renamed OttawaWhile the Bytown museum remained at the centre of the Society’s activities, the 1960s, under the leadership of Dr Bertram McKay, saw the HSO working hard for the erection of a statue in honour of Colonel By. Although Ottawa’s mayor at the time, Dr Charlotte Whitton, and City Council were supportive, it was up to the Historical Society to come up with the necessary funds. Raising $36,500 by 1969 (equivalent to more than $233,000 in today’s money), the Society hired the Quebec-born sculptor Joseph-Émile Brunet. On August 14, 1971, Governor General Roland Michener unveiled the bronze statue of Colonel By in Major’s Hill Park. Fittingly, the statue overlooked the Rideau Canal, itself a lasting memorial to the Colonel’s engineering abilities.

In Major's Hill Park stands the statue of Col. John By, Royal Engineers, who was responsible for building the Rideau Canal and the founding of Bytown, later renamed OttawaWhile the Bytown museum remained at the centre of the Society’s activities, the 1960s, under the leadership of Dr Bertram McKay, saw the HSO working hard for the erection of a statue in honour of Colonel By. Although Ottawa’s mayor at the time, Dr Charlotte Whitton, and City Council were supportive, it was up to the Historical Society to come up with the necessary funds. Raising $36,500 by 1969 (equivalent to more than $233,000 in today’s money), the Society hired the Quebec-born sculptor Joseph-Émile Brunet. On August 14, 1971, Governor General Roland Michener unveiled the bronze statue of Colonel By in Major’s Hill Park. Fittingly, the statue overlooked the Rideau Canal, itself a lasting memorial to the Colonel’s engineering abilities.

In 1981, the Society took a new step in its effort to increase public awareness of Ottawa and the Ottawa Valley’s rich history with the launch of a pamphlet series dedicated to that purpose. Its first publication was titled John Burrows and Others on the Rideau Waterway by a former Society president Charles Surtees. The pamphlet series continues to be an important feature of the Society’s efforts to increase public awareness about the history of Ottawa.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, the museum became an increasing preoccupation and concern for Society members. Forced to relocate temporarily due to restoration work conducted by the federal government at the Commissariat building and Rideau locks, attendance plummeted. Even when the Bytown Museum reopened at the Commissariat Building, the number of visitors was subsequently adversely affected by the reconstruction of Plaza Bridge. Declining membership, fewer volunteers, and rising costs owing to inflation also strained the Society’s ability to sustain the Museum in the manner it deserved. After considerable soul searching and debate, the difficult decision was made in 2003 to transfer the Bytown Museum to a separate not-for-profit organization. Roughly half of the artifacts and rare books collected over more than a century were loaned to the Museum; the loan became a permanent gift two years later. Considerable funds were also transferred to the new Museum Board to help launch the new organization.

Although now legally separate from the Historical Society of Ottawa, the Museum and the Society continue to cooperate closely. Over the following years, the Society transferred its remaining collection of items to other heritage organizations, most importantly the City of Ottawa Archives. A large collection of military medals was also offered to Canadian museums. Those medals that could not be placed were subsequently sold. In 2011, the proceeds of the sale helped to launch the Historical Society of Ottawa’s Research and Development Fund to support research into Ottawa’s history.

In 2013, the Society reviewed and approved revised “purposes and objectives” (Article 2 of its Constitution) in light of the many changes to the organization in recent years. Remaining true to the spirit of its founding members, the Society remains focused on increasing public awareness and knowledge of the history of Ottawa, the surrounding region, and their peoples. In cooperation with other heritage organizations, it also works to conserve archival materials, supports and encourages heritage conservation, and preserves the memory of Colonel By.

What We Do

The Historical Society of Ottawa (HSO) is Ottawa’s oldest historical organization. It was founded in 1898 by a group of prominent Ottawa women interested in the preservation of Canada’s rich historical heritage at a time when there were few Canadian museums and little government funding for such activities. Initially known as the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa, the Society changed its name in 1955 when men were allowed to participate as full members.

The Society’s objective is to preserve and increase public knowledge of the history of Ottawa, including its people and places, through publications, meetings, tours, awards, sponsored research, participation in local heritage events; and to support and encourage heritage conservation.

At monthly meetings, held from September to June, guest speakers inform and engage members in a wide range of topics related to the history of Ottawa and the Ottawa Valley. The monthly meetings are open to the general public as well as to members at no cost. Society members also receive a quarterly newsletter, and copies of HSO’s “Pamphlet Series” that examine local historical issues. The Society also organizes one-day bus tours for its members and guests to historic sites in Eastern Ontario and Western Quebec.

The Society is the official patron of the Ottawa Regional Heritage Fair for area youth (Grades 5-9) which is held annually. At the Fair, the Society presents awards in recognition of research excellence in subjects relevant to Ottawa’s history.

The Society welcomes everybody with a love of history and an interest in Ottawa’s heritage, irrespective of race, religion, sex, age, country of origin, or any other attribute.

The Historical Society of Ottawa is a non-profit organization and a registered charity - Registration no.: BN 10748 4081 RR 0001. To make a donation, see our online donation form. Many thanks! A charitable receipt for income tax purposes will be issued for donations. Please note that a receipt for tax purposes cannot be issued for membership fees.

The Stopwatch Gang

17 April 1974

If Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were the quintessential bank robbers of the late nineteenth century, the Stopwatch Gang was their late twentieth-century alter egos. Both gangs became infamous for their audacious heists throughout the American west. While armed robbery was their profession, the two gangs avoided bloodshed. For a time, they both ran rings around the police. They were finally brought to book but not before they entered popular folklore. The story of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid was romanticized and immortalized in the 1969 classic movie starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford. Similarly, the fascinating tale of the Stopwatch Gang has been recounted in numerous newspaper articles, books and documentaries.

The story of the Stopwatch Gang begins in, of all places, Ottawa. It was in Canada’s capital that three young men, Stephen Reid, Patrick “Paddy” Mitchell and Lionel Wright, met. Combining their skills, they pulled a daring gold heist at the Ottawa airport in 1974. Although arrested and subsequently sentenced to long jail terms, they escaped from prison, fleeing to the United States. There, the trio became known as the “Stopwatch Gang,” knocking off banks with clockwork precision. Police estimate that they stole as much as $15 million from as many as 100 banks during their crime spree. Fuelled by their illicit earnings, the gang experienced the high life. But the money quickly drained away. Life on the run was expensive and lost its allure. In a perennial search of the big score that would allow them to retire, the men began to make mistakes. With the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) as well as state and local police on their trail, the trio was finally apprehended. They had run afoul not only of the people’s law but also the law of averages.

Their story starts in 1973. Stephen Reid, a young, troubled, bank robber from Massey, Ontario who had escaped policy custody by jumping out of a restaurant window while on a day-pass from the Kingston Penitentiary, arrived in Ottawa and hooked-up with Paddy Mitchell, a handsome, articulate crook from Stittsville, a small town outside of Ottawa. Mitchell had previously taken under his wing Lionel Wright, a socially-awkward introvert with a passion for details. The duo had been stealing goods from delivery trucks, making use of information Wright received in his job as a night clerk in a shipping yard. In late 1973, Mitchell got wind of a far larger score. A crooked Air Canada baggage handler who had been thieving from Air Canada shipments, told Mitchell that Air Canada regularly shipped gold destined for the Royal Canadian Mint in Ottawa. The gold bars were temporarily stored in the freight building at the Ottawa International Airport. The baggage handler agreed to tip off Mitchell when a shipment arrived in return for a cut of the proceeds. Mitchell, Reid and Wright immediately set about planning a gold heist that would allow them to live and retire in style.

On 17 April 1974, Mitchell received word that a shipment of gold from the Campbell Red Lake Mines in northern Ontario had arrived in Ottawa on Air Canada flight 444. Five wooden boxes containing six gold bars totalling 5,167 ounces, worth $750,000 (roughly $8 million at 2016 Canadian prices) were stored in a wire security cage in the airport warehouse, awaiting pickup by armoured car.

Shortly before midnight, Reid, dressed in an Air Canada parka and wearing a counterfeit security pass, knocked on the warehouse door. When the Universal Security guard answered, Reid pulled a gun. After disarming the guard, Reid marched him over to the security cage and demanded the key. Discovering to his dismay that the key was kept overnight in the main air terminal, Reid used tools from the warehouse repair shop to snap the padlock securing the 16-by-10 foot wire cage. With the guard handcuffed to a metal pipe, and a cardboard box placed over his head, the gang loaded the gold onto a small, metal handcart for transport across the warehouse to their get-away car, a green station wagon. Although the heist took longer than expected—twenty-five minutes instead of the planned five minutes—the gang successfully eluded the roadblocks set up by Gloucester Police after janitorial staff found the handcuffed guard and raised the alarm.

From early on, police had a strong conviction that an insider was involved. How else could the thieves have known of the gold shipment? Paddy Mitchell also quickly became a person of interest. But there was insufficient evidence for an arrest warrant. The gold had vanished and nobody was talking.

Behind the scenes, Mitchell sold the gold to California mobsters for only a fraction of its market value; fencing hot bullion is not easy. After Reid left temporarily for the United States, Mitchell and Wright, running short of cash, organized an airport drug smuggling racket with the aid of their baggage-handler contact. Things started to go wrong. The cocaine were intercepted by a sniffer dog. The baggage handler also ignored Mitchell’s advice and started to spend lavishly, buying a diamond ring, a motor-cycle and a boat. Picked up by police and questioned, he squealed on the others. Meanwhile, police who had wire-tapped Mitchell’s telephone overheard him talking about the sale of the airport gold.

In 1976, Mitchell and Wright each got 17 years for cocaine smuggling. Mitchell received an additional three years for possession of the stolen bullion. Reid, although not involved in the drugs deal, was picked up for escaping custody after he had returned to Canada. Identified in the airport heist, he received an additional ten years for armed robbery. As for the gold, only a small portion was ever recovered.

With the three behind bars, one would have thought this was the end of Reid, Mitchell and Wright. But their story had only just begun. Wright almost immediately escaped from the Ottawa Detention Centre and disappeared. Reid and Mitchell were both sent to the notorious, maximum-security Millhaven Penitentiary. There, the two worked hard to become model prisoners in an effort to get transferred to a more salubrious jail. Reid even took a hair-dressing course. It was a con. Out on a day-pass to visit a hair salon, the well-spoken, polite Reid reprised his earlier jail break by convincing the accompanying policeman to stop for fish and chips. Saying he had to go to the bathroom, Reid vanished out the restaurant’s washroom window.

Mitchell too managed to escape from prison. He feigned a heart attack by poisoning himself with nicotine obtained by soaking cigarettes in water. Rushed to the hospital with chest pains, confusion and nausea, his ambulance was met by gowned hospital attendants. They were Reid and Wright. The armed duo locked Mitchell’s guards in the back of the ambulance, and transferred the near-comatose Mitchell to a Chevy van, and vanished into the night.

The trio made their way to the United States, hiding for a time in a cheap, Florida motel where Wright worked as a clerk under an assumed alias. In Florida, the gang began their crime wave, robbing a department store before shifting to banks. When things got too hot, they headed west. It was in California that the trio became known as the “Stopwatch Gang” hitting bank after bank with the same modus operandi. One man with a gun held up the place, another jumped over the counter and grabbed the cash, and a third drove the get-away car. All wore masks or disguises. One member of the gang typically carried a stopwatch around his neck. They were in and out in under two minutes.

After taking a short break, during which time Reid and Wright rented a luxurious cabin on a creek in Sedona, Arizona, the trio hit a Bank of America branch in San Diego, California in late September 1980. Mitchell was again the driver while Reid and Wright disguised with make-up, wigs, and fake beards held up the branch with an Uzi machine gun and a magnum revolver. The gang made off with US$283,000 in cash.

In their haste to get away, Wright threw their wigs, empty money bags, stolen licence plates used to disguise the get-away car, and other incriminating evidence in a nearby dumpster. The material was later found by dumpster divers looking for cans who alerted the police. Investigators were able to find a partial fingerprint on one of the Bank of America money bags. Also found was a copy of the fake car licence Wright used to rent a car. The noose began to tighten around the gang.

The trio decamped to their Sedona hide-out to enjoy their ill-gotten gains. They seemingly fitted in well into the small community, and were even befriended by the local sheriff’s deputy. Reid took flight lessons and bought a plane. But FBI agent Steve Chenoweth and his colleagues were watching and waiting. Tipped off regarding their true identities, the partial fingerprint was sent to the RCMP in Canada for positive identification. With the identity of one of the gang members confirmed, a judge provided a warrant for their arrest on bank robbery and conspiracy charges. At the end of October 1980, Lionel Wright was arrested naked in bed in the Sedona hide-out. Stephen Reid was later stopped without a struggle as he drove to the airport to go flying. By chance, Mitchell was on holiday and escaped the police dragnet.

In April 1981, Wright and Reid pled guilty to the armed robbery of the San Diego Bank of America branch. The duo each received twenty-year sentences in federal prisons; their sentences were later reduced to ten years. Both were eventually transferred to Millhaven Penitentiary in Ontario to finish their time in Canada. Here, the story takes a novel twist. Reid began to write about his experiences, producing a semi-autobiographical book called Jackrabbit Parole. In a neighbouring cell, Wright typed the manuscript. The book caught the attention of Susan Musgrave, a noted Canadian poet and editor. Reid and she started to correspond. Later, they married in the prison chapel at Millhaven. By this time, the couple had become famous; the CBC television programme The Fifth Estate was invited to the ceremony. Reid was later moved to a British Columbian prison to be close to Musgrave. He was paroled in 1987 and for a time led a model life, raising a family with Musgrave on Vancouver Island. Writing appeared to have been his salvation.

As for the other two, Wright didn’t get out of jail until the mid-1990s. He then disappeared, this time permanently. Mitchell, who remained at large after Reid and Wright’s arrest in Sedona, went solo in the robbery business. Robbing department stores and banks from Florida to Arizona, Reid became number seven on the FBI’s most wanted list. He was described as “armed and dangerous and an escape risk.” Mitchell missed his two colleagues who had previously taken care of all those important heist details. He got sloppy and was finally tracked down in early 1983 to the small town of Astatula, Florida, and was apprehended by the FBI. He was transferred to San Diego to stand trial for the Bank of America heist as well as for the robbery of an Arizona Bank. He ended up in the Arizona State Penitentiary looking at decades behind bars. But after four years, he and two other inmates successfully broke out via a ventilation shaft. He fled to the Philippines, got married, and had a son. He supported his family through an occasional trip back state-side to rob more banks. His career finally came to an end in 1994 in the little town of Southaven, Mississippi when be bungled his last bank robbery. He got 30 years in Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas. In 2006, Mitchell died of cancer in a prison hospital in Butner, North Carolina, his request to be transferred to Canada denied.

The story of the Stopwatch Gang wasn’t quite over. Stephen Reid couldn’t adapt to his new life on the outside. Back on drugs, he held up a bank in 1999 with an accomplice in Victoria, British Columbia, making off with $93,000. In the ensuing chase, he fired shots at the police. He was apprehended and sentenced to eighteen years for armed robbery and attempted murder. Returned in prison, he resumed writing. In 2013, he published a collection of essays titled A Crowbar in the Buddhist Garden: Writing from Prison. After his release from jail, he resumed his life with Susan Musgrave who stood by her man despite everything. On 12 June 2018, Stephen Reid died in a Haida Gwaii hospital in British Columbia. He was 68 years old.

Sources:

Story idea courtesy of André LaFlamme, Ottawa Free Tours, http://www.ottawafreetour.com/.

CBC, 2011. “My Friend The Bank Robber,” The Fifth Estate, 25 March.

Citizen, (The), 1974. “Airport bandits escape with $165,000 in gold,” 18 April.

—————–, 1974. “Great gold caper baffles detectives,” 19 April.

—————–, 2006. “Paddy Mitchell’s dying wish,” 30 July.

—————–, 2014. “Ottawa Stopwatch Gang’s Stephen Reid is out of prison,” 19 February.

Dean, Josh. 2015. “The Life and Times of the Stopwatch Gang,” The Atavist Magazine.

Meissner, Dirk, 2014. “Stopwatch Gang bank robber and author Stephen Reid denied full parole,” The Globe and Mail, 3 March.

Star Phoenix (The), 2007. “Time runs out on Stopwatch Gang leader,” 16 January.

Tuscaloosa News (The), 1995. “Bank robber proud of precision work,” 29 August.

Weston, Greg. 1992. The Stopwatch Gang, Macmillan: Toronto.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.