Super User

Dow’s Lake and Its Causeway

27 December 1928

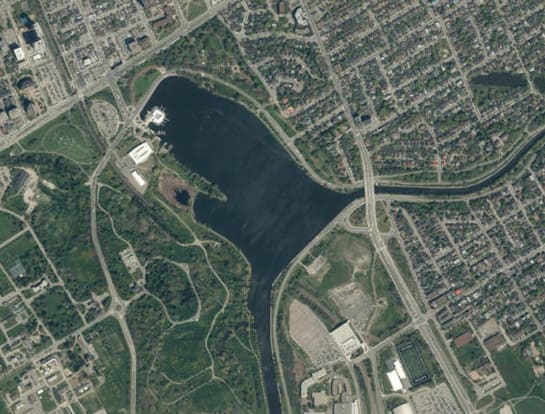

Dow’s Lake nestles in the heart of Ottawa much like a pearl in an oyster. It’s the centre of much of the city’s recreational activities, hosting skating in the depths of an Ottawa winter and canoeing and kayaking during the glorious days of summer. The boathouse at Dow’s Lake Pavilion provides welcome marina facilities for sailors travelling from Kingston to Ottawa through the Rideau Canal system. There too you will find canoes and pedalos for rent as well as restaurants to tempt the taste buds of Ottawa residents and tourists no matter the time of the year. Around the lake’s perimeter are parks, pathways and driveways frequented by joggers and cyclists. On one side is the Dominion Arboretum, part of the Central Experimental Farm, a favoured venue for picnics by families and lovers alike. On the other is Commissioners’ Park, the home of Ottawa’s annual tulip festival in May, and magnificent beds of annuals during the rest of the summer.

Of course, this was not always the case. At one time, Dow’s Lake marked the outer limits of Ottawa—beyond here be devils, or at least Nepean. But urban sprawl and amalgamation with surrounding communities have brought it well inside the Capital’s embrace. The lake is named for Abraham Dow, an American who came north in 1814 and acquired “Lot M in Concession C” in the Township of Gloucester. Samuel and Mabel Dow followed him two years later and settled nearby. Much of the Dow land was a mosquito-infested swamp that extended from the Rideau River to the Ottawa River. Roughly two-thirds of the swamp’s water flowed into the Rideau River, with the remainder debouching northward into the Ottawa River. Samuel and Mabel Dow must have despaired of their new home as they returned to the United States in 1826.

That same year, however, things began to change with the building of the Rideau Canal through Dow’s Great Swamp. To make a navigable route, Irish and French-Canadian workers, labouring under the direction of Lieutenant-Colonel John By’s Royal Sappers and Engineers, built two embankments. The first was constructed along what became the southern end of Dow’s Lake. Work on the embankment was started by a contractor named Henderson but was finished by Philemon Wright & Sons. The second, was constructed by Jean St. Louis, a French-Canadian pioneer in the region. Known as the St. Louis Dam, it blocked a creek flowing northward to the Ottawa River. The creek bed is now Preston Street. The work was difficult and dangerous. Many workers sickened with malaria. But they succeeded in raising the level of the water in the swamp to a depth of twenty feet, more than adequate for boats to traverse. Dow’s Great Swamp had been transformed into Dow’s Lake.

The new lake remained a remote place for Ottawa citizens for most of the remainder of the nineteenth century. But as the city’s population increased, the city expanded southward towards the lake, a process that was accelerated by the creation of the Experimental Farm on Dow’s Lake’s northern fringe in 1886. The extension of the electric streetcar service to the Farm ten years later turned Dow’s Lake into a popular boating and swimming area. One indignant boater of this time wrote an angry letter to the editor of the Journal newspaper complaining that foul-mouthed, naked boys were diving into the Canal at its juncture with Dow’s Lake, swimming under pleasure boats, and shocking the ladies.

In 1899, the Ottawa Improvement Commission (OIC) was formed by the Dominion Government for the express purpose of beautifying the nation’s capital which was still largely a rough lumbering town. The Commission’s first big project was the creation of the Rideau Canal Driveway, renamed three decades later the Queen Elizabeth Driveway after the wife of King George VI. The Driveway ran from downtown Ottawa at Elgin Street, along the western side of the Canal, to the Experimental Farm. This became the scenic southern gateway road into the Capital during the early part of the twentieth century. Conveniently, much of the land used for the Driveway was already owned by the Dominion government as an ordnance reserve.

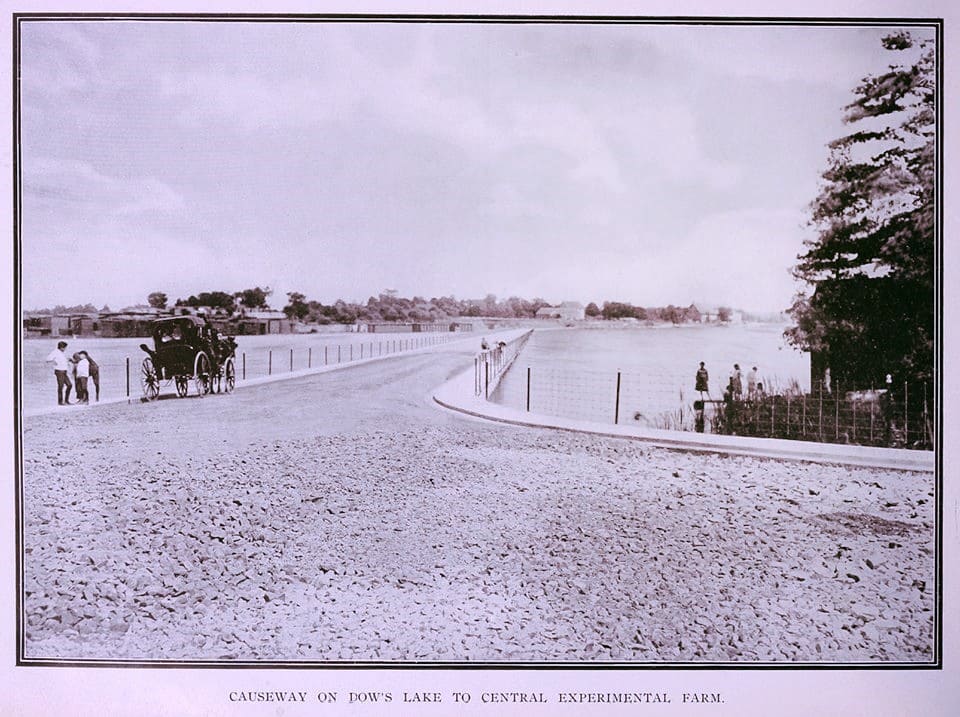

As part of the Driveway, the Commission constructed a diagonal causeway across Dow’s Lake from the eastern shore of the lake to the Experimental Farm. The first intimations of such an idea emerged in 1900 when it was revealed that the OIC was considering the building of a “pier” across the lake to the Experimental Farm, similar to the one that had just been completed at Britannia Bay. The OIC hoped that the pier would be “of ample width and character to make it one of the prettiest portions of the drive.”

In 1902, the five OIC commissioners decided to proceed. It was a close 3-2 vote. One of the dissenters was Ottawa’s Mayor Fred Cook who favoured extending the Driveway around the perimeter of the lake to the Experimental Farm instead of cutting through the lake. However, this would have meant displacing the J.R. Booth Company’s lumber piling ground located on the north-western part of Dow’s Lake close to the St.-Louis Dam. Booth had moved his lumber to this site in 1885, which was then beyond the city limits, due to concerns about the risk of fire—a not insignificant risk. But Booth was a major taxpayer and employer in the city. Weighing the economic and political risks, the Commission apparently felt it prudent to build a causeway rather than displace a company owned by one of the city’s most prominent citizens.

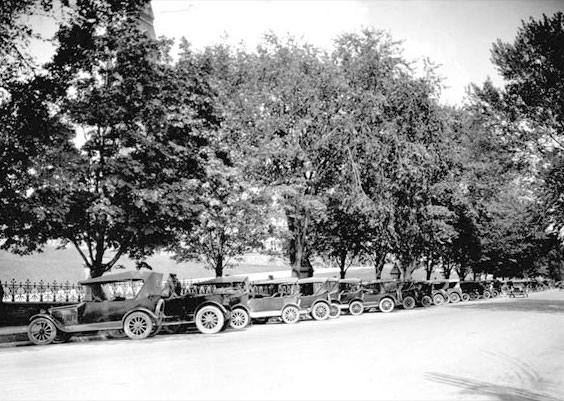

Dow's Lake Causeway to the Experimental Farm, circa 1904. Notice the macadamized road surface.

Dow's Lake Causeway to the Experimental Farm, circa 1904. Notice the macadamized road surface.

Source: Don Ross, FlickrThe causeway was constructed in 1904 linking Lakeside Avenue on the eastern side of the lake to the corner of Preston Street and the Experimental Farm, roughly where Dow’s Lake Pavilion stands today. Consequently, Dow’s Lake was bisected, with a triangular northern section cut off from the main body of water. Although the Commission got its way with respect to a causeway across the lake, it failed in constructing a huge aviary that it had hoped to build on the shores of Dow’s Lake similar to the one at the Bronx Zoo in New York. Cost was the likely factor. The Commission had planned to stock the aviary with representatives of every species of native Canadian bird.

The Dow’s Lake causeway lasted for roughly a quarter of a century. Narrow, high-crowned and unlit at night, the causeway was the location of many accidents. Apparently, the sight of automobiles being winched from the lake was not uncommon.

In 1926, the OIC, which became the Federal District Commission (the forerunner of the National Capital Commission) the following year under the direction of Thomas Ahearn, asked the Dominion Government to remove the causeway and extend the Driveway around the lake as originally championed by former Mayor Cook. In March 1927, the Railways and Canals Department of the Dominion Government agreed to demolish the causeway once 2,500 feet of new driveway had been laid through the old Booth piling grounds to the Experimental Farm.

On 27 December 1928, after the water level in the Rideau Canal had been lowered for the winter, a steam shovel began to deconstruct the causeway. Excavated material was repurposed to reinforce the retaining wall at the lake. Along the new stretch of Driveway, the FDC planted young trees to hide what was left of the Booth piling yards. The project was wrapped up by the end of March 1929. When the water was let back in the lake the following month, Dow’s Lake was restored to its full extent, much to the delight of boaters and canoeists. Residents along the lake were also pleased with the sparkling blue expanse in front of them.

All that was left of the old causeway were remnant rock piles that were covered with several feet of water. Alex Stuart, the Superintendent of the Federal District Commission, assured boaters that these rock piles would not pose a threat to navigation. He expected that there would be roughly five feet of water above the site of the old causeway, more than sufficient clearance for boats on the Canal which typically had a draught of no more than three feet. He also claimed that the action of flooding the lakebed would cause the remaining pieces of the causeway to subside.

Still, additional work was carried out in 1936 to dredge sections of the old causeway. This action enabled fish to swim into the deeper parts of the lake during the winter. It seems that the remnant foundation of the causeway was sufficiently high to trap fish once the water level in the canal and lake was lowered in the fall. During a cold winter, the shallow water remaining in the northern part of the lake froze to the bottom killing trapped fish.

Today, the causeway is all but forgotten by Ottawa residents. However, when the water is let out in the fall, traces of the old causeway in the form of low, narrow, stone islands that cross the lake can still be seen. Its location can also can be determined with hydrographic charts.

Sources:

Bytown or Bust, 2008. Dow’s Lake, Hartwell Lock and Hog’s Back, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Kingston-Wayne, 2011. Dow’s Lake Causeway.

Ottawa Journal, (The), “Chase Those Boys,” 5 July.

—————————, 1900. “A Pier Across Dow’s Lake,” 11 October.

—————————, 1904. “Proposal For Giant Aviary,” 12 March.

—————————, 1904, “Plans For The Ottawa Improvement Commission,” 7 April.

—————————, 1904. “The Ottawa Improvement Commission’s Part In Making The Capital A City Beautiful,” 16 September.

—————————, 1921. “Dangerous Driving,” 21 June.

—————————, 1926. “Have Other Plans To Provide Work,” 4 November.

—————————, 1927. “Laurier Statute Will Be Placed Before July 1,” 27April.

—————————, 1928. “Dow’s Lake Road Will Be Built In Early Spring,” 24 March.

—————————, 1928. “Start Tomorrow Remove Causeway,” 26 December.

—————————, 1929. “Familiar Crossing Over Dow’s Lake Had Now Vanished,” 3 April.

—————————, 1929. “Sees No Danger To Craft,” 4 April.

—————————, 1929. “Dow’s Lake Takes On New Beauties,’ 30 April.

—————————, 1936. “Breaking Hole To Free Fish,” 9 November.

Rideau Canal World Heritage Site, 2018, A History of the Rideau Lock Stations.

Ross, A.H.D. 1927. Ottawa Past and Present, The Musson book Company Limited: Toronto.

Urbsite, 2010. Canal Crossings,.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Canadian Army in Ottawa

September 1855

As Remembrance Day approaches, we remember the sacrifices of World Wars 1 and 2. But we also had military units in Ottawa getting ready to go to the Fenian Raids, the Northwest Rebellion and the Boer War. Regardless of the justice or non justice of these events, we still had men willing to risk their lives for the rest of us. Let's look at our involvement in these conflicts.

Some years ago, Colonel Strome Galloway who commanded the Royal Canadian Regiment in the battle for Ortona in World War 2 summarized the early history of the Ottawa military for the Historical Society of Ottawa ,and I am indebted to him for the information in this article. Mush of the early history of the military in Ottawa concerns militia or reserve units made up of ordinary citizens who “answered the call” when danger threatened. According to Galloway, no regular army fighting unit has ever been garrisoned in Ottawa. This is not true of the RCAF who based interceptor and reconnaissance squadrons here during the height of the Cold War However we are looking at a much earlier time.

Before we look at some unit histories, the “interesting” events that involved Ottawa citizen soldiers were the Fenian raids of 1866 and 1870 when the “Civil Service Rifles” were called up to repel invasion if necessary. The Governor General's Foot Guards provided several offices to command the 150 “voyageurs” who ferried British troops up the Nile river in 1884. Ottawa provided a group of 50 “sharpshooters”, mostly from the Foot Guards, to the troops dispatched to Saskatchewan at the time of the Northwest difficulties in 1885. About 100 men were provided by the 43rd Rifles and the Governor General's Foot Guards Foot Guards as reinforcements for the Royal Canadian Regiment in the Boer War of 1899 A member of the Rifles was awarded a “Queen's Scarf” of Honour for his involvement. Queen Victoria personally knitted seven scarves for special acts of valour in the field. She knitted three for the British forces and one each for Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and South African forces By the time World War 1 began in August of 1914, Ottawans were fully involved.

The first military unit organized in Ottawa was the Ottawa Volunteer Field Battery or “Bytown Gunners” which still exists today. It was formed in 1855 and its members have served in many conflicts. It's Second Battery, serving in the Boer War had among its members John McRae, later and still famous for his poem “In Flanders Fields” They have served in all wars since the, and are most recognizable for the salutes they fire on Parliament Hill on national occasions such as Remembrance Day.

The senior infantry regiment in Ottawa is the Governor General's Foot Guards, formed in 1861in Quebec City as the Civil Service Rifles. When government moved to Ottawa, so did the Rifles. During the Fenian Raids, all male civil servants were conscripted to guard government buildings—our first example of military conscription! In 1872, it was considered that he new Dominion should have a regiment of Guards, similar to those who guarded the Queen in London. The unit was modeled on the Coldstream Guards of the British Army Colours were first presented to the Guards by the wife of the Governor General in 1874 and the Cartier Square Armoury was constructed to house them and others in 1878 .By Royal decree, this Regiment has military precedence over all other Canadian regiments.

In 1881, 43rd Ottawa and Carleton Rifles became the Duke of Cornwall's Own Rifles and, in 1933, their name was changed to the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa.

In 1872, there had been organized an Ottawa Troop of Cavalry. This troop became the forerunner of the 4th Princess Louise Dragoon Guards and the 4th Hussars. WE stopped using horses in War after the First World War so most “horse regiments” became armoured units and rode tanks instead of horses

Other units assembled in Ottawa, but were not really Ottawa Units. The first, in 1898, was the Yukon Field Force which was mustered to aid the RNWMP in policing the Yukon, in face of the lawlessness associated with the Yukon gold rush. In December 1899, with the Royal Canadian Regiment already on the way to South Africa., Lord Strathcona, then Canada's High Commissioner in Great Britain offered a blank cheque to recruit a cavalry regiment to serve in South Africa. This unit became known as The Lord Strathcona's Horse In 1914, another generous person, put up $100,000 of his own money to form a regiment to be named after the then Governor General's daughter, Princess Patricia. This unit became known as the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry and has just finished a tour of duty in Afghanistan, as well as serving in both World Wars. So did the Lord Strathcona's Horse, on horses in World War 1 and in tanks in World War 2 They assembled in Ottawa so all of these units have links to Ottawa and they only represent Army units. Ottawa has contributed much to Canada's military history and that fact should be better known!

Cliff Scott, an Ottawa resident since 1954 and a former history lecturer at the University of Ottawa (UOttawa), he also served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Public Service of Canada.

Since 1992, he has been active in the volunteer sector and has held executive positions with The Historical Society of Ottawa, the Friends of the Farm and the Council of Heritage Organizations in Ottawa. He also inaugurated the Historica Heritage Fair in Ottawa and still serves on its organizing committee.

Volunteers

Central to the life of The Historical Society of Ottawa is our volunteers. Being 100 per cent volunteer operated, the Society is totally dependent on its member volunteers for all facets of its operations. If you love history and would like to get involved, we have a job for you!

By volunteering with the Society, you will be helping to preserve and share Ottawa’s rich historical heritage. You will also be using your special skills, working with interesting people who share a passion for history.

Possibilities for helping are endless. We need people of diverse backgrounds and abilities for the Society to function effectively.

If you would like to get involved, or would like to find out more about volunteer opportunities with the Society, please contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., or speak to one of the Society’s directors.

We look forward to meeting you!

Patronage of Rideau Hall

Lady Minto

Lady Minto

Topley Studio, Library and Archives Canada, 3810248Since the founding of what was then called the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898, the Society has always had a close relationship with Rideau Hall There is a belief that Lady Aberdeen, the wife of the 7th Earl of Aberdeen who was Canada’s Governor General from 1893 to1898, was the Society’s first patron. However, while we know that she took a close interest in the fledgling organization, her patronage was likely unofficial as she and her husband returned to Britain just a few days after the first regular meeting of the Society.

For certain, Lady Minto, the wife of the 4th Earl of Minto who succeeded Lord Aberdeen, consented to become the patron of the Society in February 1899. For more than fifty years, the wives of succeeding Governors General continued this practice. In more recent decades, Governors General themselves have fulfilled this role, continuing a tradition of more than a hundred and twenty years of vice-regal patronage.

Special Events

Each year, the Historical Society of Ottawa organizes special outings for members and their guests to places of historical interest in Ottawa or in the Ottawa area. Typically, these outings consist of an animated tour or presentation by a local historian followed by a lunch. Should we be heading out of Ottawa, transportation is typically arranged, usually a tour bus with bathroom facilities.

The cost of the event varies, depending on entrance and other fees, and the cost of a bus if one is hired.

To allow persons on a budget to join the Historical Society of Ottawa and to participate fully in the Society’s activities, a Bursary Fund has been established to reduce membership fees and other expenses. If you are in this position, please contact the Society at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

These events are not only informative—a way of learning about Ottawa’s history close-up—but is a fun way of socializing with people who share your interest in history.

Recent Special Events

Community Talks

The Historical Society of Ottawa provides speakers on a range of Ottawa-related historical subjects. Our presentations are particularly suited to seniors and youth groups. There is no charge for this service.

Speakers and their areas of expertise include:

James Powell

The history of Bytown and Ottawa, the assassination of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, Lady Aberdeen, Cairine Wilson, Counterfeiting in Canada, Ottawa Women on Ice, Ottawa in the 1930s, Ottawa War Stories, Ottawa the Cold War, Weird and Wacky Ottawa, and several other topics.

George Shirreff

Anything related to the history of film in Ottawa, and the Ottawa Little Theatre.

Speakers may be willing to present on other topics; they have an extensive knowledge of Ottawa history. So, if what you are looking for is not listed, please ask. It’s possible something could be organized.

To arrange for a speaker, please email The Historical Society of Ottawa at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Pamphlets

If you interested in having a more in-depth knowledge of Ottawa rich and diverse history, the HSO’ s Bytown Pamphlet series is for you!

Since the early 1980s, the Society has regularly published monographs on various aspects of Ottawa’s history. These monographs are available free to members and through the Ottawa Public Library, Library and Archives Canada, and the City of Ottawa Archives. We are currently in the process of scanning and digitizing all of our pamphlets to make them more accessible to the general public.

The first introductory pamphlet produced by the Historical Society of Ottawa contains excerpts from an address on the history of the Historical Society given by E.M. Taylor before the Ontario Genealogical Society (Ottawa Branch) on March 22, 1976.

Pamphlet Series

A number of the Society's pamphlets are available in digital format to download free of charge.

Heritage Events

Heritage Day

Heritage Day is part of Heritage Week, a nation-wide celebration that encourages all Canadians to explore their local heritage, to get involved with stewardship and advocacy groups, and to visit museums, archives, and places of significance. Heritage Day is a time to reflect on the achievements of past generations and to accept responsibility for protecting our heritage.

Ottawa Regional Heritage Fair

Aimed at students in Grades 4-10, the Fairs inspire young people to explore the many aspects of Canadian history, heritage and culture in a dynamic learning environment and to celebrate the results of their efforts at a public exhibition.

Colonel By Day

Colonel By Day takes place on the holiday Monday in August each year, close to the Colonel’s birth date of August 7, 1779. This popular summer event named in Colonel By’s honour celebrates Ottawa’s history and heritage with open air events, walking tours and a host of family friendly, heritage-themed activities.

BIFHSGO Annual Conference

"Genealogy always reminds me of a treasure hunt: we use our investigative skills to find the genealogical nuggets left behind about our ancestors. BIFHSGO’s annual conference provides a wonderful opportunity to advance one’s knowledge, expand one’s skills and meet a community of like-minded people."

– BIFHSGO Past President Duncan Monkhouse

“Hello Ottawa–Hello Montreal”

20 May 1920

At the turn of the twentieth century, radio was the new, cutting-edge technology. Building on the work of others, including Nikola Tesla, Édouard Branly, and Jagadish Bose, the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi established in the early years of the century a wireless telegraph system using a spark-gap transmitter that could send transatlantic radio messages in Morse code. The first such radio transmission, greetings from U.S. President Roosevelt to King Edward VII, was sent in 1903. Subsequently, ships began to be equipped with radio transmitters and receivers; radio distress signals sent by the RMS Titanic using Marconi equipment are credited with saving hundreds of lives in 1912. The Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden demonstrated the feasibility of audio radio using continuous waves by sending a two-way voice message in 1906 between Machrihanish, Scotland and Brant Rock, Massachusetts. On Christmas Eve of that year, he broadcasted a short programme of music by Handel, his own rendition of some Christmas carols, and a reading from the Bible to ships at sea along the eastern seaboard of the United States from his Brant Rock base of operations. World War I brought further major technological advances, including the invention of the vacuum tube and the transceiver (a unit with both a radio transmitter and receiver), that spurred the development of commercial radio. By 1920, the world stood on the cusp of a new radio age with instantaneous, wireless, audio communication and entertainment.

On 19 May 1920, the Royal Society of Canada convened in Ottawa for its 39th Annual Meeting. The Society had been founded in 1882 with the patronage of the Governor General, the Marquis of Lorne, to promote scientific research in Canada. Society fellows gathered at the Victoria Memorial Museum for the opening of the conference, chaired by the Society’s president, Dr R. F. Ruttan of McGill University, and for the election of new fellows. They subsequently broke into specialist groups, to hear addresses on a variety of topics, including plant pathology, and the properties of super-conductors. That evening, President Ruttan gave the presidential address in the ballroom of the Château Laurier Hotel. The topic of his speech was “International Co-operation in Science.” The general public was cordially welcomed to attend this presentation, and another to be held the following evening at the same venue by Dr A.S. Eve, also of McGill University.

Dr Eve’s lecture commenced at 8.30pm on 20 May. Its intriguing title was “Some Great War Inventions.” Among the discoveries he discussed was the detection of submarines. Canadians had been on the forefront of this research, starting with Reginald Fessenden who pioneered underwater communications and echo-ranging to detect icebergs following the Titanic disaster. Subsequently, Canadian physicist Robert Boyle developed ASDIC in 1917, the first practical underwater sound detector machine, or sonar, for the Anti-Submarine Division of the Royal Navy. At the evening’s presentation, Dr Eve also demonstrated the advances made in the radio-telephone. At 9.44pm, the Society fellows and members of the public heard the words “Hello Ottawa—Hello Montreal” over a large loudspeaker called a “Magnavox,” set up in the Château Laurier’s ball room. The first public wireless conversation in Canada had begun.

For two days, engineers from the Canadian Marconi Company in Montreal and officers of the Naval Radio Station on Wellington Street in Ottawa had laboured to prepare for the event. The experimental radio station, located on the top floor of the Marconi building on William Street in Montreal, operated under the call letters “XWA” for “Experimental Wireless Apparatus.” It had first gone on the air on 1 December 1919 on an experimental basis. Another transmitting and receiver station was established at the Naval Radio Station, with a secondary receiving station set up at the Château Laurier, with an amplifier to ensure all attending Dr Eve’s presentation could hear the broadcast. At the Montreal end, Mr J. Cann, chief engineer for the Marconi Company, was in charge, while at the Naval Radio Station in Ottawa was Mr Arthur Runciman, also from the Marconi Company. Assisting Runciman were engineers, Mr D. Mason, and Mr J. Arial. Also present were Mr E. Hawken, the commanding officer of the Marine Department, and his wife. Stationed at the receiving station in the Château Laurier were Commander C. Edwards, director of the Canadian Radio Service and Lieutenant J. Thompson, his assistant. Journalists covering the historic radio broadcast were based at the Naval Radio Station.

Following the introductory exchange of words, the notes of “Dear Old Pal of Mine,” a 1918 hit song, sung by the Irish tenor John McCormick and played on a phonograph in Montreal, could be distinctly heard in Ottawa. This was followed by a one-step ballroom dance tune popular at the time. So well could the orchestra be heard, the Ottawa Journal reporter wrote that some of his colleagues listening to the broadcast at the Naval Station actually started an impromptu dance.

After the dance tune, one of the radio operators in Montreal delivered a speech prepared earlier by Dr Ruttan on behalf of the Royal Society of Ottawa in which he congratulated the Marconi Company and the Radio-Telegraph Branch of the Department of Naval Service for “their generous co-operation in this difficult scientific experiment.” Following a short pause, Society follows were treated to a live performance from Montreal of the early nineteenth century Irish folk ballad “Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms,” written by the Irish poet Thomas Moore and sung by vocalist Dorothy Lutton. She sang a second song, “Merrily Shall I Live” as an encore.

It was then Ottawa’s turn to communicate to Montreal. The Ottawa operator first explained the radio experiment to his listeners. This was followed by Mr. E. Hawken singing the first verse of “Annie Laurie,” an old Scottish song that begins “Maxwelton’s braes are bonnie.” Receiving a wild round of applause from his Château Laurier audience, Hawken was persuaded to sing the second verse. Hawken’s performance was followed by the transmission of several dance tunes played on a phonograph. The evening’s programme concluded with hearty congratulations sent in both directions.

Dr Eve’s demonstration of radio telephony was deemed a huge success. The wireless operators in Ottawa and Montreal were elated. Never before had two-way radio communication had been achieved over such a long distance—110 miles (177 kilometres). The broadcast, at least at the Ottawa end, and especially at the Château Laurier where the signal was boosted by an amplifier, was generally clear and distinct. However, listeners at the Marconi station in Montreal had a more difficult time picking up the signal from Ottawa. Marconi officials explained that reception was adversely affected by interference from Montreal’s large buildings. There were apparently some tense minutes as Montreal listeners wearing headphones tried to decipher the sounds coming from the capital.

The broadcast launched Canada into the radio age. Some radio historians argue that the 20 May radio performance by Marconi’s XWA station to the Royal Society’s meeting in Ottawa was the first scheduled radio broadcast in Canada, and possibly the world. XWA became CFCF in November 1922. Reputedly, the call letters stood for “Canada’s First, Canada’s Finest.” The station’s call letters were changed to CIQC in 1991, and to CINW in 1999. The station went off the air in 2010.

Sources:

Broadcaster, 2001, 100 Years of Radio: Celebrating 100 years of radio broadcasting.

Historica Canada, Broadcasting.

The Citizen, 1920. “May Meeting of The Royal Society of Canada Opens,” 19 May.

The Gazette, 1920. “Wireless Concert Given For Ottawa,” Montreal, 21 May.

————–, 1920. “Heard In Ottawa.” Montreal, 21 May.

The Ottawa Journal, 1920. “Ottawa Hears Montreal Concert Over the Wireless Telephone, Experiment Complete Success,” 21 May.

Université de Sherbrooke, Bilan du Siècle, “Diffusion d’une émission radiophonique directe, ”.

Vipond, Mary, 1992. Listening In: The First Decade of Canadian Broadcasting, 1922-32, Carleton University Press: Ottawa.

Image: CFCF Radio, Montreal, author unknown, Université de Sherbrooke, Bilan du Siècle, “Diffusion d’une émission radiophonique directe,”.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Parking Meters Arrive in Ottawa

25 April 1958

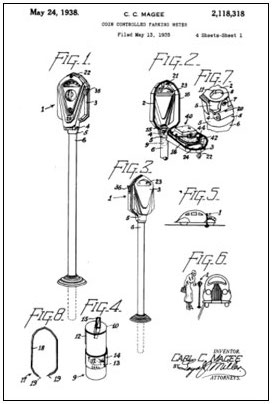

By the time of the Great Depression the automobile had replaced the horse-drawn carriage. In 1929, five million cars were produced in the United States, with another quarter million made in Canada. City streets were becoming clogged with vehicles, and parking was becoming a serious problem everywhere. Through the working week, people drove their vehicles to downtown offices, and parked them on neighbouring streets for eight hours or longer. This left little room for shoppers. Although the Depression drastically slowed the production and sale of cars, it didn’t solve the parking problem. Carl C. Magee, a noted American publisher, came up with a solution–the coin-operated parking meter. (Magee had become prominent during the 1920s for publicizing the Teapot Dome Scandal, the biggest U.S. political scandal prior to Watergate, that led to the Secretary of the Interior being jailed for corruption.) Magee, in cono-operation with University of Oklahoma engineers Holger Thuesen and Gerald Hale, developed a working prototype. In May 1935, Magee filed a patent in the United States for a coin-controlled device, receiving U.S. patent 2,118,318 three years later for his invention. American cities took to the new invention like proverbial ducks to water as a way of encouraging motorists to vacate parking spaces. The fact that parking meters were a real money spinner certainly helped too. Meters paid for themselves in four or five months.

Parking meter image from Carl C. Magee's patent application for the coin operated parking meter filed 15 May 1935.

Parking meter image from Carl C. Magee's patent application for the coin operated parking meter filed 15 May 1935.

Patent received 24 May 1938, U.S. Patent OfficeOklahoma City installed Magee’s “park-o-meter” its streets in July 1935, just weeks after Magee filed his patent application. Reporting on the event, The Ottawa Journal called the new device the “automat of the curbstone,” describing it as “a metal hitching post with meter attached” that promised “to solve the pest of the streets – ‘the parking hog.’” It opined that people will be watching the experiment with great interest.

Ottawa wasted little time in exploring the possibility of introducing parking meters to the streets of the nation’s capital. In 1936, City Council received an offer from one O. G. O’Regan to install parking meters in downtown Ottawa. In a letter, O’Regan explained that the cost of the meters would be paid by parking fees, and that after the costs were met, the revenue would accrue to the city. Ottawa’s Board of Control said that O’Regan should speak to the Automobile Club, the Board of Trade and other groups to educate the public about such a drastic change in parking regulations. In an editorial the Journal said that the parking meter was “so new that probably many people are unfamiliar with it.” Assessing the pros and cons of a trial, the newspaper argued that if free street parking is not a “right,” then Ottawa might as well make some revenue from it “if the privilege is to be extended.” Also, if meters reduced casual parking, merchants might benefit. However, the newspaper was uncertain whether Ottawa citizens would take kindly to the idea, and wasn’t sure if meters could be used with parallel parking.

Ottawa did not take kindly to the idea. It took three attempts and twenty years before City Hall got the votes to install meters. On the first attempt in 1938, the Traffic Committee and the Board of Control recommended the installation of 903 meters in downtown Ottawa for a six-month trial period. Supporters of the measure hoped that meters would be more effective than existing parking regulations in curbing lengthy parking stays. In 1937, 14,000 parking tickets were handed out to motorists who had overstayed the 30-minute parking limit, but only 900 fines were issued. Opponents argued that instead of unsightly meters, parking problems could be addressed through the enforcement of existing rules. Mayor Stanley Lewis opposed meters as did merchants who feared losing business if free parking was eliminated. A concession on the part of meter supporters to reduce the charge for the first twelve minutes to only one cent was not sufficient to change minds. With Toronto and Montreal having turned down metered parking, Council rejected meters on an 18-8 vote. The measure was put onto the backburner for a decade.

Parking on Wellington Street in front of Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 1920s - already a problem. Notice the row of stately elm trees that lined the sidewalk. Sadly, they all succumbed to Dutch elm disease mid-century.

Parking on Wellington Street in front of Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 1920s - already a problem. Notice the row of stately elm trees that lined the sidewalk. Sadly, they all succumbed to Dutch elm disease mid-century.

Department of the Interior / Library and Archives Canada PA-034203In 1947, the issue resurfaced. By this time, meters had apparently been installed in 1,200 U.S. cities and 49 Canadian communities, including Kingston, Oshawa and Windsor. Once again, the Traffic Committee and the Board of Control favoured their introduction. But Stanley Lewis, who still occupied the mayor’s chair, remained a steadfast opponent. At Council, the debate was fierce. Supporters argued that metered parking would allow for a more equitable distribution of limited parking spaces, would speed up business, reduce congestion, and increase municipal revenues. The anti-meter faction argued that meters would ruin the look of Ottawa, would clutter sidewalks, and that shoppers would avoid areas that had metered parking. Some also contended that metered street parking was a “nuisance” tax on motorists, and that their advantages were unproven. One alderman suggested that to reduce congestion, he would ban all parking on Bank and Sparks Streets, and convert part of Major Hill’s Park into a parking lot. “The park is only frequented by tramps, and the public do not go there.”

In December 1947, Council narrowly voted (12-10) in favour of installing parking meters for a one-year trial, and issued a request for tenders. One would think that this would have been the end of the matter—far from it. Two firms, the Mi-Co Meter Company of Montreal and the Mark Time Meter Company of Ottawa, submitted bids for the contract. Early the following year, the Board of Control selected Mi-Co on the basis that it offered the lowest price. However, City Council subsequently rejected the Mi-Co bid in favour of Mark Time meters. While Council did not have to select the lowest bid, the rationale for overturning the Mi-Co bid was murky. The Mi-Co Meter Company, whose meters were actually made in Ottawa by a company called Instruments, Ltd, indicated that it would seek an injunction to stop the city from signing a contract with Mark Time on the grounds that it had won the tender since its meters were cheaper and conformed to City specifications whereas Mark Time meters did not. Among other things, the City had specified that the dial indicating the amount of time available was to be visible on both sides of the meter. This requirement that was not met by Mark Time meters. After another stormy Council session, Council voted 17-7 to rescind the awarding of the contract to Mark Time. It was a pyrrhic victory for Mi-Co. Ten days later City Council overturned the parking meter trial on an 18-2 vote. According to the Ottawa Journal, this decision “positively, definitively, officially and finally” meant that parking meters would not be installed on Ottawa streets.

With the parking debate in abeyance in Ottawa, Eastview (Vanier), which was a separate municipality, got a jump on its municipal big sister by introducing parking meters in May 1951 along Montreal Road. The charge was one cent for the first twelve minutes and five cents for an hour of parking time from 8am to 8pm Monday to Saturday. The experiment was a great success with congestion along Montreal Road substantially reduced. The fine for a parking violation was $1 if paid within 48 hours at the police station, or $3 if the infraction went to court.

Shortly afterwards, despite the “definitive” decision not to install parking meters in neighbouring Ottawa, the City Council’s Traffic Committee again recommended the installation of meters on certain Lowertown streets and well as on Lyon, Sparks and Queen Streets. But with Charlotte Whitton assuming the mayor’s chair in 1951, the recommendation went nowhere. The pugnacious and irascible Whitton was dead set against parking meters. “[If] we want space on our streets for moving traffic, we surely don’t want to rent out public streets and give people the right to store their cars there,” she said. She favoured more off-street parking instead.

It wasn’t until after Whitton had been dethroned in 1956 that the parking meter issue resurfaced in any significant manner at Ottawa City Council. By this time, meters had become a familiar part of the urban landscape in most North American towns and cities. Toronto had succumbed in 1952 and Montreal two years later. The Journal newspaper had also for several years run a series of favourable articles on the success of meters in other towns in curbing traffic congestion and, incidentally, raising huge sums for municipal coffers. These articles were helpful in preparing the ground for parking meters. In mid-December 1957, Ottawa’s Civic Traffic Committee unanimously recommended the installation of parking meters, the last outspoken critic of the machines on the Committee having thrown in the towel. A few days later, City Council passed the measure virtually without debate, agreeing to install meters in central Ottawa in the area bounded by Laurier, Kent, Wellington and Elgin as well as in Lowertown along Rideau from Mosgrove (located where Rideau Centre is today) to King Edward and along bordering side streets for one block.

To help avoid the contract problems that the City had ten years earlier, precise specifications were issued in the call for tenders. Four companies—Sperry Gyroscope Ottawa Ltd with its Mark Time meter, the Duncan Parking Meter Company of Montreal with its Duncan “50” and Duncan “60” models, The Red Ball Parking Meter Company of Toronto, and the Park-o-Meter Company also of Toronto—submitted bids to install 925 meters. Nettleton Jewellers examined the clockwork mechanism of all test machines submitted with the tenders. The winner was the Duncan Parking Meter Company of Montreal for its economy Duncan “50” model at $55 each.

Within weeks of the tender being accepted in February 1958, meter poles began to sprout on Ottawa streets. After testing, the first meters went “live” on Rideau Street on Friday, 25 April 1958. Traffic Inspector Callahan said that the meters were effective immediately and “must be fed” wherever they had been installed. Motorists were also given instruction on how to park—with front wheels opposite the machines. If a car occupied more than one space, both meters would have to be fed, five cents for 30 minutes, 10 cents for an hour. It was also illegal for motorists to stay longer than one hour; topping up the meter was not permitted. A parking infraction led to a $2 ticket. The meters were a great success, especially financially. The meters began pulling in $3,500 per week, considerably more than had been expected, with annual maintenance and collection expenses placed at only $20,000.

Over the next half century, the ubiquitous parking meter ruled downtown curbsides, standing every car length or two depending on whether single-headed or double-headed machines were being used. But in the 2000s, single-space curbside meters began to give way in Ottawa to multi-space machines (Pay and Display) that gave motorists a slip of paper that indicated the expiry time to be placed on the dashboard. This innovation permitted more cars to be parked on a given street, and eliminated “free” parking when a motorist parked in a spot with unused time on a standard meter. It also helped to reduce the clutter of unsightly meters on city sidewalks.

Other technological advances are also reducing the number of parking meters. Some communities have adopted in-vehicle parking meters—an electronic device that motorists can charged up and display on a car window. Others have embraced pay-by-phone parking with licence plate enforcement. In 2012, pay by telephone parking arrived in Ottawa through a system called “PaybyPhone” that is available in major cities around the world. After registering, a motorist enters a location number and selects the desired length of parking time up the permitted maximum. The parking charge is automatically debited to a credit card. Parking enforcement officers have a hand-held device that has real-time access to licence plate numbers and paid vehicles.

Looking forward, one can envisage further technological changes that could accelerate the demise of the parking meter, including in-car sensors and shared, autonomous vehicles that people call when needed. The parking meter, even the modern, multi-space machines now found on Ottawa streets, may soon become as rare as a telephone call box.

Sources:

Everett, Diana, 2009. “Parking Meter,” Oklahoma Historical Society.

Google Patents, 2017. Coin Controlled Parking Meter, US2118318 A, Inventor: Carl c Magee, May 24, 1938.

Grush, Ben, 2014, “Smart Attrition: As the parking meter follows the pay phone,” Canadian Parking Associatio.

Ottawa, (City of), 2017. How to pay for parking, http://ottawa.ca/en/residents/transportation-and-parking/parking/how-pay-parking.

Ottawa Sun, 2012. “Pay by phone parking arrives,” 5 April.

Ottawa Citizen, 1958. “Something Has Been Added,” 19 April.

Ottawa Journal, 1935. “The Automat of the Curbstone,” 29 July.

——————-, 1936. “Parkometer Proposal Is Referred To Board,” 22 September.

——————-, 1936. “Parking By Meter,” 23 September.

——————-, 1936. “Consider Parkometer Plan,” 23 September.

——————-, 1938. “No Harm In Trying The Parking Meters,” 16 April.

——————-, 1938. “Council Rejects Parking Meter Plan,” 21 June.

——————-, 1948. “Ottawa Firm Seeks Injunction to Restrain Meter Negotiations,” 10 June.

——————-, 1948. ‘“In Again, Out Again Meters’ Voted Out at Council Caucus,” 12 June.

——————-, 1948. “Right Decision on Parking Meters.” 19 June.

——————-, 1948. “And Now Let’s Forget Them!” 23 June.

——————-, 1950. “Parking Meters Approved For Eastview,” 26 October.

——————-, 1951. “134 Parking Meters Go In At Eastview,” 7 May.

——————-, 1951. “Eastview Find Parking meters Clear Montreal Road,” 16 June.

——————-, 1953. “Down With Meters Says Mayor,” 23 December.

——————-, 1957. “Board of Control,” 13 December.

——————-, 1957. “Parking Meters,” 17 December.

——————-, 1958. “Six companies Tender On Meters,” 29 January.

——————-, Parking Meter Proposal Submitted,” 31 January.

——————-, 1958. “Ottawa Buys 1,000 Parking Meters,” 18 February.

——————-, 1958. “Rideau Street Parking Meters In Operation,” 25 April.

——————-, 1958. “Meters Earn $3,500 A Week,” 14 August.

PaybyPhone, 2017. Welcome to PaybyPhone, Ottawa.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.