Super User

The Nabu Network

26 October 1983

By the early 1980s, Ottawa was a hot-bed of high tech activity. Surrounding established companies, such as Bell Northern Research and Mitel, a cluster of small, ambitious telecommunications and computer-related firms with exotic names had emerged. These included Gandalf Data, Norpak, Xicom, and Orcatech, to name but a few. Many fizzed for a while, only to quickly disappear due to competition, rapidly changing technology, weak consumer demand, and inadequate funding. One that for a time stood out from the pack was NABU. Named for the Babylonian god of wisdom and writing, NABU was an acronym for “Natural Access to Bidirectional Utilities.” In its initial incarnation, the start-up was formally known as NABU Manufacturing Corporation. It was listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange in December 1982, raising $26 million in its initial public offering. The Ottawa-area company was itself the product of a number of mergers and acquisitions, including Bruce Instruments of Almonte, a manufacturer of remote television converters, Computer Innovations, a seller of computer hardware and software, Mobius Software, Andicon Technical Products of Toronto, a producer of small business computers, Volker-Craig of Kitchener, a manufacturer of video-display terminals, and Consolidated Computer Inc.(CCI), a relatively large, but troubled, government-owned, Canadian computer manufacturer and distributor. NABU bought CCI for one dollar from the federal government after the company had burned through $118 million of taxpayers’ money.

With close to 900 employees, half of whom were based in the Ottawa area, NABU had a multi-faceted business strategy. First, it planned to take on the business market, selling desk-top computers for word processing and data management. Initially producing the NABU 1100 in its Almonte plant, it released the 16-bit NABU 1600 in 1983. The 1600 version had 256 kilobytes of random-access memory (RAM), expandable to 512K, and a 10-megabyte hard drive, and used Intel’s 8086 processor. (Today’s laptop computers have eight to sixteen gigabytes of RAM, with up to 4 terabytes of hard drive, though with cloud computing, the sky is the limit for data storage.) It also came with a high density mini-floppy disk drive with storage for 800K of formatted data. Three people could use the NABU computer simultaneously doing different tasks. The price for the NABU 1600 was a breathtaking $9,800, equivalent to more than $21,000 in today’s money.

Second, NABU aimed to produce the first Canadian microcomputer for home use, taking on the likes of Commodore, IBM, Xerox, and a fledgling company that had gone public in December 1980 called Apple Computer. Third, the company envisaged selling on-line services to households. After buying or renting a NABU home microcomputer, and using its television as a monitor, a family could access programmes and data stored in NABU’s central server (a DEC mainframe) through a cable company’s broadband network. As the transmission of television signals only used a portion of the information-carrying capacity of cable networks, there was ample space for the transmission of other data-carrying services without degrading the television signals. The speed that the data could be transmitted on the coaxial cables employed by the cable companies (6.5 megabits per second) was also hundreds of times faster than what could be achieved over telephone lines.

By joining what was advertised as the NABU Network, cable company subscribers who bought the NABU package of services would have access to a wide range of educational and financial programmes, video games, news, weather, sports, and financial data including stock market quotations. In addition to consulting the Ottawa Citizen’s “Dining Out” guide, subscribers could read their daily horoscope, learn to type, balance household budgets, and improve their maths skills. A number of video games were also developed specifically for NABU with the help of another talented Ottawa firm, Atkinson Film Arts, featuring the comic strip characters, the Wizard of Id and B.C. In one game, called The Spook, billed to be superior to the popular arcade game Pac-Man, a player could guide a character through the dungeons of the kingdom of Id to freedom. Subscribers also had access to the space games Demotrons and Astrolander, a tennis game, and a downhill skiing game.

An even more outstanding feature of the NABU Network was two-way communication made possible by Telidon, a videotext/teletext service developed by the Canadian Communications Research Centre. NABU envisaged subscribers doing their banking and shopping from the comfort of their home. Also possible were electronic mail and remote data storage—an early form of cloud computing. In essence, NABU had foreshadowed today’s wired world, a decade before the launch of the Internet.

After rolling out their home computers at the end of May 1983, NABU launched its Network services in Ottawa on 26 October 1983. Initially, the service was only available to Ottawa Cablevision subscribers, i.e. people who resided west of Bank Street. One could purchase the NABU home computer for $950, or rent the unit for $19.95 per month, plus an addition $9.95 for NABU’s “lifestyle software.” For this price, one received the NABU 80K personal computer, a cable adaptor, a keyboard, a games controller, and thirty lifestyle games and programmes; the inventory of games and programmes later rose to roughly one hundred. For an extra $4.95 per month, subscribers had access to LOGO, an educational-based programming language, and LOGO-based programmes. NABU executives hoped to receive orders from at least five per cent of Ottawa Cablevision’s 90,000 customers within six months. In early 1984, the service was made available to subscribers of Skyline Cablevision, i.e. people who resided east of Bank Street. The plan was to introduce the NABU Network to forty cities across North American by the end of 1985. NABU’s first foray into the U.S. market took place in Alexandria, Virginia, close to Washington D.C., in the spring of 1984. To lead the U.S. charge, NABU hired Thomas Wheeler, former president of the US National Cable Television Association.

Unfortunately, things did not go as planned. When NABU’s line of business computers failed to meet expectations, the company hunkered down to focus on its more promising NABU Network. A corporate restructuring at the end of October 1983 led to the NABU Manufacturing Corporation being split into two companies, the NABU Network Corporation and Computer Innovations. The latter company quickly disappeared into oblivion. NABU Network struggled on for a time. By late 1984, it had about 1,500 customers in the Ottawa region, and a further 700 in Alexandria. This was not enough to make the enterprise viable. With the home computer market seen as being too competitive, the company de-emphasized its proprietary hardware to focus on the delivery of its software. In in a last ditch effort to attract subscribers, adaptors were offered so that owners of Commodore and other home computers could access the NABU Network.

It was not enough. In November 1984, the Campeau Corporation, NABU’s principal shareholder and largest creditor, pulled the plug on the failing enterprise. Having already invested more than $25 million, and, with little indication that NABU could attract sufficient subscribers to break even, let alone turn a profit, Campeau was unwilling to pour more money into the venture. NABU’s remaining 200 employees were laid off. John Kelly resigned as CEO and chairman of the NABU Network Corporation. Trading in NABU Network shares were suspended, with the company de-listed from the Toronto Stock Exchange in January 1985. When it finally provided financial statements as of September 1984, the company had assets of only $4 million, with liabilities of $30 million. NABU shares, which were sold for $12.75 each at the company’s IPO two years earlier, were worthless.

Still confident about the concept of linking home computers to a central server using cable networks, Kelly formed a new, private company called the NABU Network (1984) to continue providing programmes and video games under licence to NABU subscribers in Ottawa; the U.S. service in Alexandria was discontinued. The new successor company hired back roughly 30 of the staff previously laid off. Subscriptions were sold door-to-door by Amway. Forever the optimist, Kelly hoped to have 6,000-8,000 subscribers by the summer of 1986. It was not to be. Limping along for eighteen months, the company ceased operations at the end of August 1986. The NABU Network dream was no more.

Why did NABU Network fail? In 1986, Kelly attributed its failure to the network concept being “ahead of its time,” and a slump in the home computer industry that killed the NABU personal computer. Part of the problem was that home computers themselves were not widely accepted; relatively few homes had them in the mid-80s. Many saw them as expensive toys rather than an indispensable part of everyday life. Content on the NABU Network was also an issue. Thomas Wheeler, who headed the company’s U.S. operations, and who is currently the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the United States, attributed the company’s failure to its dependence on cable company operators for its subscribers. In contrast, America Online (AOL) in the United States, which launched a similar, but far inferior, dial-up service in 1989, was wildly successful, at least for a time. Wheeler credits AOL’s success to it being available to anyone with a telephone and a modem. Ironically, cable companies later became important internet service providers.

In 2005, the York University Computer Museum began a programme to reconstruct the NABU Network, and develop an on-line collection documenting the NABU technology. It called the NABU Network “a technologically and culturally significant achievement.” Four years later, the Museum’s version of the NABU network was officially demonstrated. There for the event was John Kelly, NABU’s president and chief executive officer.

Sources:

IEEE Canada, 200? (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), The Internet Before Its Time: NABU Network in the Nation’s Capital.

McCracken, Harry, 2010. “A History of AOL, as Told in its Own Old Press Releases,” Technologizer, 24 May.

Montreal Gazette (The), 1983. “Nabu banking on its ‘network.’” 18 November.

———————–, 1985. “Amway to sell Nabu software,” 29 January.

———————–, 1985. “Nabu files statement,” 1 March.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1982. “Nabu goal: To make first Canadian microcomputers,” 23 March.

——————-, 1982. “Nabu adds videogames to service, 31 May.

——————-, 1982. “Nabu teaches computer ‘albatross” how to fly again,” 8 December.

——————-, 1983. “Nabu 1600 hits market across U.S., 27 May.

——————-, 1983. “Nabu 16-Bit Micro Features Intel 8086, 8087 Co-Processors,” 26 October.

——————-, 1983. “World’s first cable-TV computer on line,” 26 October.

——————-, 1983. “The Magic of The Nabu Network, 28 October.

——————-, 1984. “Skyline cable custmoers to get Nabu Network,” 25 April.

——————-, 1984. “Nabu Network reports $2.5 million loss,” 29 May.

——————-, 1984. “Role of Nabu’s own computer played down,” 19 June.

——————-, 1984. “Nabu proving technology before any expansion,” 19 June.

——————-, 1984. “Nabu chief forms new company,” 23 November.

——————-, 1985. “Trading stopped on Nabu shares by Ontario Securities Commission,” 24 January.

——————-, 1986. “Plug finally pulled on failing Nabu Network,” 19 July.

Reyes, Julian, 2014. “How Tom Wheeler Almost Invested The Internet,” Fusion, 27 May.

Wheeler, Tom, 2015, “This is how we will ensure net neutrality,” Wired, 4 February.

York University, 2009. NABU Network Reconstruction Project at YUCoM, (York University Computer Museum).

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Water Woes

23 August 1912

Pure, sparkling clean, tap water. We tend to take it for granted. Occasionally our complacency is shaken, as it was in 2000 when seven people died in Walkerton, Ontario when e. coli contaminated the town’s drinking water. But, thankfully, that was a rare event. Ottawa’s tap water consistently gets top grades for quality. Raw water from the Ottawa River is filtered and chemically treated in several steps to remove bacteria, viruses, algae, and suspended particles. More than 100,000 tests are conducted each year to ensure that crystal clear, odourless, and, above all, safe water is supplied to Ottawa’s households and businesses.

But this was not always the case. One hundred years ago, two old, poorly maintained intake pipes that drew untreated water from mid-river were the source of the city’s water supply. But the Ottawa River was dangerously polluted. The region’s many lumber mills routinely dumped tons of waste each year into the river. Decomposing sawdust was actually responsible for the death of a man from Montebello in 1897 when he was thrown from his boat by a methane explosion. Meanwhile, raw sewage from Ottawa’s burgeoning population, as well as from Hull and other riverside communities, was simply flushed into the river. Sewage from inadequately maintained outdoor privies also leaked into the region’s many creeks and streams that fed the Ottawa River. It was a recipe for typhoid fever.

While typhoid stalked all major Canadian cities during the first years of the twentieth century, Ottawa was among the worst affected. The disease annually claimed on average twenty lives, a shockingly high number for a community of perhaps 75,000 souls. Most of the deaths were recorded in the poor, squalid districts of Lower Town and LeBreton Flats. Civic officials, at best complaisant, at worse criminally negligent, did nothing. It was perhaps easier, and cheaper, to blame the poor’s unhygienic living conditions than to do something about the water supply. But even the death in 1907 of the eldest daughter of Lord Grey, the Governor General, who had been visiting her parents from London, didn’t prompt action.

Ignorance wasn’t a viable defence for civic leaders’ lack of action. By 1900, health officials were very familiar with Samonella enterica typhi, the bacteria that caused typhoid, and how to combat it. They were fully aware that the most common form of transmission was drinking water polluted by human sewage. They also knew that chlorine could be used as a disinfectant, rendering the water safe for consumption. Typhoid was a fully preventable disease.

In 1910, an American expert was finally called in to look at ways of improving Ottawa’s water supply. He recommended the immediate addition of hypochlorite of lime, a bactericide, as an interim remedy until a mechanical filtration plant could be constructed. Alternatively, he proposed that cleaner, albeit much more expensive, water be piped in from Lake McGregor in the Gatineau Hills. His report was shelved.

Disaster struck in early January 1911. In the space of weeks, there were hundreds of typhoid cases in the city. By the end of March, sixty people had died. By year-end, the death toll had reached eighty seven. Even before the epidemic had run its course, the first investigation by the chief medical health officer of Ontario concluded that it was due to contaminated city water. Owing to low pressure, an emergency intake valve in Nepean Bay had been opened to raise water pressure in case of fire. The intake had sucked in raw sewage into the water mains. The source of pollution was traced to Cave Creek (now a sewer) that ran through Hintonburg, a heavily populated area which relied on outdoor privies that emptied into the creek. Blame for the epidemic was placed squarely on civic officials who had done nothing to ensure a safe water supply for Ottawa citizens. A second study concluded that had hypochlorite of lime been added to the city’s water as recommended in the 1910 study, the outbreak could have been averted.

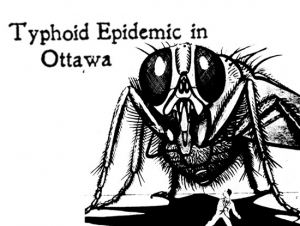

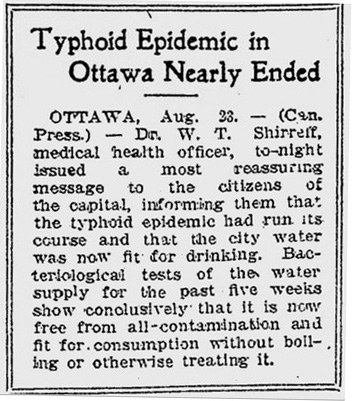

Ottawa press statement falsely indicating the end of the 1912 typhoid epidemic

Ottawa press statement falsely indicating the end of the 1912 typhoid epidemic

The Toronto World, 24 August 1912Some modest steps were taken to address the situation. Hypochlorite of lime was finally added to the water, but various technical problems prevented the full amount of the chemical from being used. A new intake pipe was also put down in 1911 and was in use by the following April. But the water remained contaminated as a significant portion of the city’s water continued to be sourced through the old, leaky intake pipes. Although Ottawa’s engineer warned city officials that the water supply remained in a dangerous condition, nothing further was done.

In June 1912, typhoid returned to Ottawa with a vengeance. So bad were conditions that MPs were reluctant to return to Ottawa for the autumn1912 parliamentary session, and lobbied for Parliament to be shifted at least temporarily to Toronto, or even Winnipeg. More radical voices wanted Canada’s capital to be moved permanently if Ottawa could not provide government workers with clean water. The Toronto World thundered that the city was advertising itself “from Vancouver to Halifax as a pest hole of diseases.”

With the disease striking during the prime tourist season, civic and business leaders were keen to play down the extent of the problem and the underlying causes. In mid-August, a secret meeting was held between business leaders, Mayor Charles Hopewell and the city’s medical officer of health to discuss the impact of the epidemic on commerce. On 23 August, the medical officer of health announced that the “typhoid epidemic had run its course” and that the water was now safe to drink; bacteriological tests for the previous five weeks having showed “conclusively” that the water was free from contaminants and was “fit for consumption without boiling or otherwise treating it.” It was a barefaced lie. Cases of typhoid continued to occur. Tragically, there were twelve additional deaths in September and a further nineteen in October, weeks after the epidemic had supposedly ended. In total, roughly 1,400 cases of typhoid were recorded in 1912 with 98 fatalities. In November 1912, City Council self-servingly declared that it was “not legally responsible to the [typhoid] sufferers, but only morally so.” It voted a mere $3,000 to cover urgent relief needs.

This time a judicial inquiry was held into the two epidemics. An investigation by provincial authorities indicated continued gross contamination of the water notwithstanding what the medical officer of health had said. It was also shown that contamination occurred due to leaks in both old and new pipes. The city engineer was suspended and Ottawa’s medical officer of health resigned. Although there was insufficient evidence to indict Mayor Hopewell, his reputation was ruined. He declined to run again as mayor in the 1912 election. In 1914, the provincial board of health concluded that “after careful investigations” the outbreaks of typhoid fever were “caused by the use of sewage-polluted water from the Ottawa River.” It added that it was “a disgraceful fact that up to the present date no satisfactory plan for a pure supply for that city has been adopted.”

While repairs were made to the intake pipes and the water was treated with ammonia and chlorine, it was only a temporary fix to Ottawa’s water woes. A permanent solution had to wait almost twenty years as debate raged on city council and in the courts between those that supported the purification of Ottawa River water and the “Lakers” who wanted to pipe in clean water from 31-Mile Lake or Lake Pemichangan north of the city in the Gatineau Hills. Construction on the Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant finally began in 1928. When the plant opened three years later, Ottawa finally had safe tap water.

Sources:

Bourque, André, 2013. City of Ottawa Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant (82 Years Young and Going Strong), Atlantic Canada Water & Wastewater Association.

City of Ottawa, 2014. Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant.

H2O Urban, 2008. Ottawa Report, 22 November.

Jacangelo, Joseph G. and Trussell, R. Rhodes, 2009. “International Report: Water and Wastewater Disinfection: Trends, Issues and Practices,.

Lloyd, Sheila, 1979. “The Ottawa Typhoid Epidemics of 1911 and 1912: A Case Study of Disease as a Catalyst for Urban Reform,” Urban History Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, p. 66-89.

Murray, Mathew, 2012. Dealing with Wastewater and Water Purification from the Age of Early Modernity to the Present: An Inquiry Into the Management of the Ottawa River, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, University of Ottawa.

Ottawa Riverkeeper, 2007. Notes on a Water Quality and Pollution History of the Ottawa River.

Provincial Board of Health, 1914. 1913 Annual Report.

The Citizen, 1912. “City’s Responsible for Typhoid Claims,” 12 November.

—————–, 1913. “Harsh Condemnation of Ottawa’s Civic Government by Members of Commons in Discussing Pollution of Streams Bill,” 26 April.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1953. “History of Ottawa’s Water System Long and Bloody One,” 28 April.

The Evening Telegram, 1907. “Earl Grey’s Daughter Dead,” 4 February.

The Toronto World, 1912. “M.P.’s Afraid To Go To Ottawa,” 5 August.

——————-, 1912, “Typhoid Epidemic in Ottawa Nearly Over,” 24 August.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Bob, the Fire Horse: The End of an Era

25 September 1929

On 25 September 1929, The Ottawa Evening Journal reported the death of old “Bob,” a twenty-five year old horse. It was front page news as Bob wasn’t just any horse but was Ottawa’s last fire horse. The red ribbon and cup winner at the Ottawa Horse Parade passed away in pasture, honourably retired for more than a year. He had been purchased by the Ottawa Fire Department (O.F.D.) in 1908 at the age of four from Hugh Coon. Standing 16 hands, 2 inches tall (66 inches) from the ground to the top of his withers, the jet black, 1,300 pound horse served four fire stations during his lifetime, retiring from the No. 11 station at 424 Parkdale Avenue. Old Bob wasn’t the last horse in active service, but was the last owned by the O.F.D. In late 1928, the last two-horse team, also at service at No. 11 station, was displaced when the O.F.D. purchased three motorized combination ladder and hose trucks. When the team was sold, only Bob was left, pensioned off in recognition of his many years of noble service to the City. His retirement to greener pastures was controversial. Ottawa City Controller Tulley opposed Bob’s pensioning. A delegate to the Allied Trades and Labour Association meeting held in Ottawa in the fall of 1928 wanted to know if Tulley thought the old horse deserved to be shot, and whether the councillor favoured the same treatment be given to other old employees.

Bob’s passing marked the end of an era dating back to 1874 when the City purchased the first horses for its fire department. Prior to then, firemen had to pull their fire engines manually to the scene of a fire. The first fire engine in the city dated back to 1830 when the British regiment stationed on Barracks Hills, now called Parliament Hill, acquired the Dominion, a small manually operated machine. A volunteer fire department was formed in 1838. Later, the first fire hall was established on the ground floor of Bytown’s (later Ottawa’s) City Hall on Elgin Street. During these early years, insurance companies played a major role in fire-fighting, even providing the fire equipment. The first fire stations date from 1853 when the Bytown Town Council established three “engine” houses in West, Central and East Wards, each equipped with hand-pulled engines. In 1860, the now City of Ottawa purchased two hook and ladder trucks. As each weighed more than a ton, they were supposed to have been drawn by horses. But the City was too cheap or too poor to provide the funds for horses so the engines had to be manually pulled to fires.

The volunteer fire department was neither well managed, nor very professional in its operations. According to David Fitzsimons and Bernard Matheson who wrote the definitive history of the Ottawa Fire Department, there were complaints in the 1850s of volunteers who were quick to show off their sky-blue and silver laced uniforms in parades, but were no-shows when there was an actual fire. To “secure the utmost promptitude in the attendance of the different [fire] companies and water carriers at fires,” the City began to offer in the mid-1860s significant financial premiums to first responders. “The first engine to arrive in good working order” received $12, the second $8. The first water carrier received $2 and the second $1. Although such financial incentives did indeed encourage prompt service, they also led to fisticuffs between competing firemen with fires sometimes left unattended. Even when fire fighters managed to arrive at a fire without delay, there was the occasional problem. In 1914, Mr. J. Latimer, a fire department veteran, recalled a major fire in the Desbarats building located on the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets that occurred in February 1869. When the fire threatened to spread to the neighbouring International Hotel, barrels of liquor were rolled out into the street to keep them safe from the flames. In the process, some were broken open and at least two detachments of firefighters went home “wobbly” and had to be replaced before the fire was extinguished.

The first fire horses arrived in 1874 when the City acquired the Conqueror steam engine with a vertical boiler from the Merryweather Company of Clapham, England for the huge sum at the time of $5,953. Considerably heavier than other fire equipment, Ottawa was obliged to buy horses to pull it—anywhere from three to six depending on weather and road conditions. That same year, Ottawa’s volunteer fire department was replaced by a professional, full time force under the leadership of Chief William Young and Deputy Chief Paul Favreau.

The first motorized fire engines were introduced in North America during the first decade of the twentieth century. In 1906, the Waterous Engine Works Company of Saint Paul, Minnesota and Brantford, Ontario produced the Waterous Steam Pumper. That same year, the Knox Automobile Company of Springfield, Massachusetts produced its motorized fire engine. Such machines quickly became popular with fire departments everywhere. Compared with horse-drawn engines, the new motorized engines were faster and cheaper to operate. Horses needed to be fed 365 days of the year, and required stabling, shoeing, harnesses, and veterinary care. Fire horses also needed to be well trained. They had to be strong, obedient, and willing to stand patiently regardless of weather conditions, noise, and swirling hot embers, flames and smoke. Motorized fire engines didn’t need to be trained, were impervious to weather, and consumed gasoline only when used.

Ottawa purchased its first motorized fire engine in 1911 following pressure from insurance companies that threatened to raise their rates if the City didn’t get into the twentieth century and acquire modern fire-fighting equipment. Chief John Graham was also insistent that the City buy motorized fire equipment for efficiency and effectiveness reasons. Although the initial outlay for a motorized fire truck was higher than that of a traditional horse-drawn vehicle, the operating costs were lower.

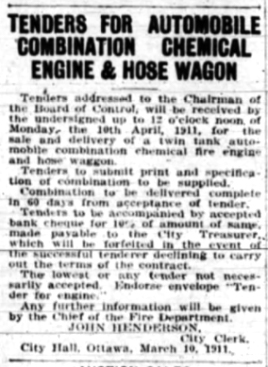

Call for Tenders for Ottawa's first motorized fire engine,

Call for Tenders for Ottawa's first motorized fire engine,

10 March 1911, The Ottawa Evening JournalChief Graham had recommended buying a motor fire truck costing $10,450 from the Webb Motor Fire Apparatus Company of St Louis, Missouri. However, City Council chose a vehicle produced by the W.E. Seagrave Fire Apparatus Company of Walkerville, Ontario (now part of Windsor), the Canadian subsidiary of a company of the same name that had been established in Ohio in 1881. The company had previously sold three of its motorized fire engines to Vancouver in 1907 and one to Windsor in 1910. The four-ton, 80 h.p. Seagrave vehicle purchased by Ottawa carried a price tag of $7,850. It was a combination chemical and hose truck capable of carrying ten firemen, two 35 gallon tanks of fire-suppressing chemicals, 1,000 feet of 2 ½ inch hose, a twelve-foot ladder plus extension, door openers, and three fire extinguishers. Fully loaded, the vehicle could attain a speed of up to 50 miles per hour on flat terrain (typically 35 mph), or 20 mph on a 5-10 per cent incline. The City had initially sought a combination automobile pumper truck with a pumping capacity of 700-800 gallons per minute. However, it opted instead for the chemical and hose truck on the grounds that a pumper truck had not yet been adequately proven though tests were underway in New York City on such vehicles.

The new Seagrave truck was shown off to Ottawa residents at the end of May 1911 when it was run out on the road with its siren shrieking for the first time. Chief Graham invited reporters to witness the truck take him, two deputy chiefs and several firemen on a tour of Ottawa along Rideau, Sparks, Bank, Elgin, Laurier and Albert Streets. It visited No. 3, 7, and 2 fire stations before parking at its new home at No. 8 station located to the rear of the Ottawa City Hall on Elgin Street. In town for the event was Mr W.E. Seagrave himself and an instructor, Mr C.E. Fern, who drove the vehicle that first time. Fern taught Fireman James Donaldson of No. 9 station how to drive the newfangled machine.

The Seagrave Chemical Hose Combination Truck, Ottawa's first motorized fire truck, 1914

The Seagrave Chemical Hose Combination Truck, Ottawa's first motorized fire truck, 1914

Topley Studio / Library and Archives Canada / PA-032798

The Ottawa Evening Journal hoped that the purchase of the Seagrave vehicle marked the start of a complete replacement by Ottawa of its horse-drawn vehicles by motorized fire trucks. (The second motorized vehicle purchased by the O.F.D. was a flash car for Chief Graham who could then retire his horse and buggy.) At that time in 1911, Ottawa’s fire department owned 46 horses, for which the cost of feed alone amounted to $4,600 per year. This was the department’s second largest budgetary item after paying the firemen’s salaries. On top of this were the ancillary costs associated with owning and taking care of horses that needed to be regularly replaced. The newspaper thought that by 1931, the whole O.F.D. might be equipped with motorized vehicles. This was a pretty accurate guess, with the motorization process taking twenty-seven years.

Chief Graham & assistants in auto "Fire Brigade," 1911

Chief Graham & assistants in auto "Fire Brigade," 1911

William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-010055The last major event that saw horse-drawn engines in action was the fire that consumed the old Russell Hotel in the middle of April 1928. By the end of that year, the entire Ottawa Fire Department had been motorized, leaving only old “Bob” to live out his days in green pastures far from the smoke and flames of his fire-fighting days.

Today, the Ottawa Fire Department has forty-five fire stations strategically positioned to protect close to one million people living in an area of 2,796 square kilometres. Among its equipment are pumper trucks, ladder trucks, rescue trucks, and brush trucks as well as boats, ATVs and other rescue equipment.

Sources:

Fire-Dex, 2011. The Switch from Horsepower to Motorized Fire Apparatus, September.

Fitzsimons, David R. & Matheson, J. Bernard, 1988. History of the Ottawa Fire Department, 150 Years of Firefighting, 1838-1988, Kanata: J. B. Matheson and D. R. Fitzsimons, publishers.

Morgan, Carl, 2015. “Seagrave: Birthplace of the Modern Firetruck,” Walkerville Times Magazine.

Ottawa, City of, 2017. About Ottawa Fire Services.

Ottawa Evening Journal, 1911. “Fire Chief Wants A Motor Engine,” 26 January.

——————————, 1911. “City Will Purchase An Auto Fire Engine,” 10 February.

——————————, 1911. “Read Tenders For Furniture,” 7 April.

——————————, 1911. “Deputy Chief At Eganville,” 12 May.

——————————, 1911. “Using Automobiles For Fire Purposes,” 29 April.

——————————, 1911. “Shriek of New Engine Was Heard,” 1 June.

——————————, 1914. “With the Ottawa Fire Fighters In Bygone Days,” 7 March.

——————————, 1928. “Labor To Take Keen Interest In Coming Vote,” 22 September.

——————————, 1928. “Only Two Horse In Fire Service,” 9 November 1928.

——————————, 1929. “Last Fire Horse Dies In Pasture,” 25 September.

——————————, 1930. “Chief Burnett Dies At Home Was Long Ill,” 3 November.

Saskatoon, City of, 2000. History of Webb Motor Fire Apparatus.

Wildfire Today, 2016. Horse-drawn fire engines.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa's Street Railways

29 June, 1891

With all the growth in our City in the past fifty years, I wonder how many people remember the days when you could take a streetcar from, among other routes, from the old train station out to Rideau and Charlotte? Thanks to Professor Don Davis of the University of Ottawa we have a detailed history of the streetcar system and how it grew and how it was eventually done away with! (see Keshen and St. Onge eds, Ottawa—Making a Capital).

Ottawa's street railway system died in 1959 after a life of 68 years. Did citizens love or hate the system? Davis notes that the love of the system was like some marriages—initial great enthusiasm followed by many years of declining interest in our rapidly changing technological world. Perhaps the streetcar era has lessons to teach in the consideration of expanded light rail?

The new streetcar system was opened on June 29, 1891—largely as a result of the work of two local entrepreneurs, Thomas Ahearn and Warren Soper. Everyone thought that such a project would fail because of Ottawa's winters. However, at the time, unless you could afford a horse and buggy plus sleigh in the winter, there was no way to get around the growing city except by walking. The system proved to be an immediate success, even in the winter. The system had the first electrically heated cars in Canada, maybe even the world. The Ottawa Car Manufacturing Company made streetcars that were exported to other parts of Canada. In the early days of the system, “ridership” rose seven times faster than the population. In 1921 at the peak of the system. Each citizen took an average of 336 rides per year. The fares were low—about three tickets for ten cents Despite attempts at updating and revival, Ottawa's Street Railway went steadily downhill from this point....

Public love for the automobile was probably a contributing factor, as was the rising costs of maintenance, expanding the roadbed and new streetcar technology The investors also played a part as they took an increasing amount of dividends out of the system and did not develop a good reserve fund for necessary expansion and repairs. By 1924, the automobile was using up the space needed for transit cars.. They blocked the progress of streetcars by parking on city streets, forcing other cars to drive on the track allowance and stopping to pick up passengers and make left turns. Streetcar trips became longer. Davis points out that “trains in 1956 were slower than they had been in 1901. Downtown it was faster to walk”.

Having made money for years, the owners of the OER now wanted to sell the system to the city. While the City Council was willing to buy, assuming they would have a monopoly on inner city transit. But, over a five year period to 1929, plebiscites were rejected four times. The taxpayers did not want to pay. In January, 1924, the City and the OER reached an agreement to extend the service and monopoly for five years, subject to renewal in 1929. This agreement created more problems than it solved. First, the carfare was frozen at five cents per ride, lower than nearly all other North American systems, and the five year term was not conducive to the kind of capital investment that was becoming increasingly necessary. Thanks to the increasing competition from the automobile, streets became even more clogged and streetcar trips ever longer. In 1929, it was apparent that new equipment was necessary, and the five year contract emboldened the owners to buy new equipment with borrowed money. Contracts were let and then came October 1929. Pressure for loan payment became intense but the fare was still frozen at five cents. When authority was finally obtained to raise the fare to seven cents, “ridership” dropped by 16%, despite a revenue increase of 10%. The OER staggered on until the end of World War 2, but the handwriting was on the wall revenues could never match increasing costs of new equipment, track extensions, competition from the auto and pressures from various interest groups. For example, Glebe residents would not permit streetcar routes along residential streets, The forerunners of the NCC did not want unsightly power lines overhead and riders demanded more comfortable and frequent service The federal government increased business taxes enormously during the War. Trams were crowded and noisy—people preferred buses before the environmental effects of buses were discovered. Despite the eventual creation of the Ottawa Transit Commission in. 1947/48 these questions continued and new ones arose. It was obvious—too many groups wanted the tram lines to disappear. By 1958/59 the pressures became too much and the old streetcar lines were removed. The only mourners at the time were the older population who had fond memories of the great days before and during the First World War.

Cliff Scott, an Ottawa resident since 1954 and a former history lecturer at the University of Ottawa (UOttawa), he also served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Public Service of Canada.

Since 1992, he has been active in the volunteer sector and has held executive positions with The Historical Society of Ottawa, the Friends of the Farm and the Council of Heritage Organizations in Ottawa. He also inaugurated the Historica Heritage Fair in Ottawa and still serves on its organizing committee.

The Maxwell Challenge

22 February 1912

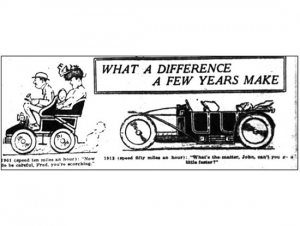

By the beginning of the second decade of the twentieth century, the automobile was no longer the delicate, temperamental curiosity that it was just a decade earlier. In ten years, the internal combustion engine used in most automobiles had been largely perfected. The one-cylinder vehicle, common at the turn of the century, which was noisy, slow and rough to drive, had evolved into a multi-cylinder machine that was, according to the Ottawa Evening Journal, not only a “thing of beauty” but “whisks by you on the street to the tune of a quiet purr, suggesting the passing of a contented cat.” Luxuriously appointed, such cars could go 50 miles per hour compared to less than 20 miles per hour achieved by vehicles a decade earlier, assuming of course drivers could find roads that were not potholed and heavily trafficked by pedestrians and horses.

For the majority of people, however, owing an automobile was a dream rather than a reality. Prices were high relative to incomes, especially during the years prior to the introduction of the assembly line that lowered production costs. In 1912, there were only 500 automobiles cruising the streets of the capital, up from a dozen ten years earlier. Demand was growing rapidly, spurred by the motor car’s many advantages over a horse-drawn vehicle. While the initial outlay for a car or truck was substantial, motor vehicles were more convenient, faster, and could carry heavier loads over longer distances, though winter motoring was problematic. Macdonald & Co., the concessionaire for Albion vans, advertised that the van “could do the work of six horses.” But the automobile’s appeal went far beyond the practical or the economic. In 1912, the Journal summed up the automobile’s almost irresistible appeal. “To own a motor car and enjoy the numerous pleasures that such affords is to own a kingdom. The driver’s seat is a throne, the steering wheel a sceptre, miles are your minions and distance your slave.”

Hundreds of small automobile companies sprang up across North America and Europe to meet the burgeoning demand for cars and trucks. Even Ottawa sported its own automobile manufacturer—the Diamond Arrow Motor Car Company. At its peak, the firm employed as many as twenty mechanics at its plant located at the corner of Lyon and Wellington Streets, just a short walk from Parliament Hill, with a showroom at 26 Sparks Street. Sadly, the firm only produced cars from 1910 to 1912, and disappeared without a trace like so many of the small, craft-style producers, a victim of strong competition, high costs, and the inability to take advantage of economies of scale.

In mid-February 1912, Ottawa held its first automobile show, hosted by the Ottawa Valley Motor Car Association founded five years earlier. The show, which attracted thousands, was held in Howlick Pavilion at the Exhibition Grounds. (The Howlick Pavilion, also known as Howlick Hall or the Coliseum was knocked down in 2012 to make way for the redevelopment of Lansdowne Park.) Some 37 different automobile marques from Canada, the United States, and Europe were on display, ranging in price from an economical $495 to a princely $10,000. Some brands, such as Rolls-Royce, Ford, Oldsmobile and Cadillac, remain household names today. But most, like Jackson, Russell, Tudhope, and Hupp, are long forgotten except by auto historians and antique-car enthusiasts. Show goers were wowed by the latest advance in automobile technology, the self-starter. No longer did a car owner have to get out and manually crank the vehicle to get it started. The 1912 Cadillac also boasted electric headlights—a first in the motoring world. Up until then, car headlamps were filled with oil and acetylene, and had to be manually lit.

With a crowded field, dealers sought ways of standing out among their competitors. Messrs Wylie Ltd of Albert Street advertised that by buying a Tudhope, a Canadian-built vehicle, purchasers avoided the 35 per cent duty levied on the imported cars. Their advertisement argued that the $1,625 Tudhope should be compared “point to point” to imported cars selling for $2,300. The American-made Cutting, selling for $1,725, boasted of its “big, husky power plant;” the Cutting had participated in the first Indianapolis 500 in 1911.

Old Ottawa City Hall, Elgin Street, site of the first leg of the Maxwell Challenge

Old Ottawa City Hall, Elgin Street, site of the first leg of the Maxwell Challenge

William James Topley, Library & Archives Canada, Mikan No. 3325359Mr F.D. Stockwell, the eastern Canadian distributor of Maxwell motor cars, manufactured by the United States Motor Company, believed action spoke louder than words. To prove the superiority of his automobile, he loaded his Maxwell touring car with twenty boys and drove it up the steps of Ottawa’s City Hall—a considerable feat given the number of steps and the sharp incline. He then drove the car through the deep snow surrounding the building, and pulled a standard car, allegedly twice the weight of his Maxwell, out of a hole. Leaving City Hall, he repeated his stunt on Parliament Hill, driving up the main walkway and up the steps leading to the front of the Centre Block. He again demonstrated the Maxwell’s ability to plough through deep snowdrifts—an important selling feature for cars at the time since few streets and highways were cleared of snow.

After a copycat repeated the stair trick within a half hour of Stockwell’s stunt, and another competitor called the Stockwell’s actions “cheap advertising,” Stockwell retorted that both had ignored “the snow tests.” He then issued the following challenge.

If there is a man in Ottawa selling a touring car from $1,000 to $10,000 (any standard stock touring car, 5 to 7 passengers, not a stripped chassis or runabout), who will drive his machine up the terrace at the City Hall through the snow bank (not doing the path cut through by the Maxwell) we will immediately deposit $100 against one or more cars depositing a like amount for a contest to take place immediately at the Parliament grounds, or anywhere there is a field of good, deep snow.

The proceeds of the bet would got to the charity of the winner’s choice.

Stockwell invited all of Ottawa to come and see who would “meet the Maxwell at the snow plow game.” While he conceded that there were other good cars, he noted that the Maxwell was the only car that for two consecutive years had completed the Glidden tour with a perfect score. The Glidden tour was an American long-distance, automobile, endurance event that began in 1905. The 1911 tour, held in October of that year, was 1,476 miles long from New York to Jacksonville, Florida. It was the most gruelling event up to that time, with the course running along treacherous roads and across streams. Recall this was long before the United States had constructed its inter-state highway system.

Maxwell Car Advertisement, 1912 (US market)

Maxwell Car Advertisement, 1912 (US market)

History of Early American Automobile Industry, 1891-1929The gauntlet was thrown down at 12.30pm on Thursday, 22 February in front of the Ottawa City Hall. Only the Peerless Garage Company, located at 344-348 Queen Street, the distributor of Cadillac, arrived to pick it up. The judges of the challenge were: Mr R. King Farrow, Mr E. H. Code and Alderman Dr Chevrier. What transpired was not exactly what Stockwell, the Maxwell distributor, had in mind.

At City Hall, the Cadillac went first, easily going up and over the building’s terrace without stopping. Stockwell, the driver of the Maxwell, refused to do likewise, but instead shouted out to the other participant “Come up where we will find some real snow at the Parliament Buildings.” The challenge was immediately accepted. On Parliament Hill, the Maxwell went first, having the choice of where to drive. Unfortunately, the automobile had gone only a few yards before it got stuck in a snowbank. Then, it was the Cadillac’s turn. Starting approximately fifteen feet from where the Maxwell had began, the Caddy drove five to seven times further across the snow-covered lawn in from the Centre Block, thereby winning the $100 wager. The Peerless Garage Company donated its winnings in equal amounts of $25 to four Ottawa charities—the “Protestant Home for the Aged” on Bank Street, the “Protestant Orphans’ Home” on Elgin Street, the “St Patrick’s Orphans’ Home” on Laurier Avenue West, and the “Perely Home for Incurables” located on Wellington Street.

Maxwell’s Stockwell immediately issued a second “Maxwell Challenge.” In a letter to the Evening Journal, he admitted that the Cadillac was a good car, and that “it proved a good snow plow, and was cleverly driven.” After adding that the Cadillac cost $600 more than the Maxwell, and that its wheels were two inches higher, Stockwell attributed the Maxwell’s loss to the “misfortune” of having run into a snowbank deposited by a plough before the car got to the open field. After being pulled off the snowbank, he said that the Maxwell had been able to pass the Cadillac that had foundered in deep snow, “its wheels suspended and running freely in the air.” Consequently, Stockwell claimed that the Maxwell was still the champion. He then sent a letter to the Peerless Garage asking for a rematch “on a course which will permit both cars to enter freely the open field, then let the best car win.” He then handed a $100 wager to the sporting editor of the Citizen newspaper, asking him as well as representatives of the Evening Journal and the Ottawa Free Press to act as judges. When the Cadillac representative refused the challenge, Stockwell upped the wager to $150 from him, against $125 from Cadillac, and set the date of the second challenge to the following Saturday afternoon, 25 February, to take place on the snow-covered lawns of Parliament Hill.

Advertisement, 1912 Cadillac, a winner of the first Maxwell challenge, 22 February 1912

Advertisement, 1912 Cadillac, a winner of the first Maxwell challenge, 22 February 1912

The Evening JournalThere was no sign of Cadillac that Saturday afternoon. With the field to himself, Stockwell demonstrated the proficiency of the Maxwell motor car in front of a large crowd of spectators. The Journal reported that the automobile entered the field near the foot of the main steps and slowly circled the field, ploughing gracefully through every ice and snow obstacle. “The Maxwell cut through the biggest drifts on Parliament Hill with consummate ease and was only forced to stop through a broken chain grip.” Stockwell then drove the car down the main walkway “amidst enthusiastic applause” from an appreciative audience.

So, who won the Maxwell Challenge? Clearly, the Cadillac won the first challenge. But, Maxwell achieved at least a moral victory through its subsequent, uncontested challenge match. However, in the highly competitive world of the automobile, Cadillac was the ultimate victor, becoming a North American synonym for luxury and success. The Maxwell, on the other hand, disappeared shortly after the First World War, a victim of the post war depression and large debts. The Maxwell Motor Car Company was purchased by Chrysler in 1921. The last Maxwell was produced in 1925 and was replaced by the Chrysler Four.

Sources:

71st Revival AAA Glidden Tour, 2016. History, 1904-1913.

Bowman, Richard, 2016. Maxwell: First Builders of Chrysler Cars.

Evening Journal (The), 1910. “First Made In This City,” 29 August.

—————————, 1912. “Ottawa, A Popular Motor Car Centre,” 10 February.

—————————-, 1912. Cutting Cars, 1912. “Gather ’round—Come Close—Listen!,” 10 February.

—————————-, 1912. “Motor Car Driving A Recreation In Ottawa,” 10 February.

—————————-, 1912. “A Maxwell Challenge, $100,” 21 February.

—————————-, 1912. “Stockwell Motor Company of Montreal Issued Challenge,” 23 February.

—————————-, 1912. “Cadillac Easily Defeats Maxwell,” 23 February.

—————————–, 1912. “Re that Automobile Competition, Maxwell Challenge No. 2, 23 February.

—————————–, 1912. “The Maxwell Challenge Was Not Accepted,” 26 February.

Macdonald & Company, 1912. “The Albion,” The Evening Journal, 10 February.

Messrs Wylie Ltd, 1912. “What does 35% duty add to the value of a Car?” The Evening Journal, 10 February.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa’s First Newspaper

24 February 1836

On 24 February 1836, the first edition of the first local newspaper appeared on the streets of Bytown, the small village that was destined to become Ottawa. That newspaper was called The Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate. Its banner on the front page under its name proudly read:

“Let it be impressed upon your minds, Let it be instilled in your children, that the Liberty of the Press is the Palladium of all your civil, political and religious rights.—Sumus.”

The newspaper’s proprietor and editor was James Johnson. An Irish Protestant, Johnson had come to Canada in 1815. In May 1827, he settled in Bytown, which had only been founded the previous year. Reportedly a blacksmith by trade, Johnson quickly became a man of considerable property, earning a living as a merchant and auctioneer in the rough, tough frontier community that was Bytown.

The establishment of a newspaper in the small community was no easy feat, and must have taken many months in put into effect. Johnson purchased his press in Montreal. He personally disassembled it and packed the pieces along with its moveable type in boxes for shipment to Bytown. Most likely, he sent the equipment via boat as there were no railways or good highways linking Bytown to the outside world.

The Prospectus of The Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate was dated December 16, 1835, indicating that Johnson had been working on the newspaper for several months before he released its first issue. He committed to publishing the newspaper every Thursday until demand was such that a semi-weekly publication was warranted. He intended “to advocate the national character and interest of every true Briton—Irishmen and their descendants first on the list.” In addition to being the spokesman for the Irish, Johnson promised to “promote the interests and prosperity of the County of Carleton and the Province [Canada West, i.e. Ontario] in general.” However, he also promised to take “the occasional peep into the affairs of our Sister [Canada East, i.e. Quebec]” since the prosperity of the two Provinces were tightly connected.

Johnson proclaimed that on “all occasions,” the newspaper will “uphold the King, and Constitution by enforcing obedience to the laws.” “May the Union Jack of Great Britain never cease to proudly wave over the Citadel of Quebec,” he declared. However, Johnson was very clear that his allegiance did not extend to the King’s ministers and officers, many of whom he believed incompetent and who put their own self-interest ahead of that of the citizens of the two Provinces. He said that they should be “turned adrift to gain a livelihood by their own industry.” Johnson added that “at all times,” would the newspaper speak out against “any misapplication of public monies, or malefaction with which public officers may be charged.”

One thing the newspaper would not do is to wade into religious controversies, except if “a wonton attack is made upon any body of Christians.” Johnson wrote “every man should be allowed to walk in his own peaceful ways without intolerance, as he is responsible for them to God alone.”

The cost of subscribing to the newspaper, which Johnson promised to publish on “good paper” of “a fair size,” was an expensive £1 or $4 per year, exclusive of postage payable semi-annually in advance. Rates for advertising in the newspaper were set at 2 shillings and sixpence for six lines for the first insertion, with every subsequent insertion set at 7 1/2d. Rates went up for larger advertisements. From six to ten lines, the initial rate was 3s. 6d. with subsequent insertions costing 10d. For submissions of great than ten lines, the rate would be 4d. per line for the first time, and 1d. per line for subsequent insertions.

That first edition had a run of about 500 copies, four pages long, which he produced with the help of John Stewart, his compositor. Johnson tried to deliver by hand all the copies of that inaugural issue of the Bytown Independent as he didn’t want to use the Post Office. Johnson, an irascible and opinionated man, was angry at Bytown’s Deputy Post Master and didn’t want to give him the business. “We have always been ill treated by the Deputy Post Master,” he raged. “To have him enlarge his bags for five hundred copies of the Bytown Independent would be unreasonable on our part.”

Johnson requested that friends and foes alike peruse the newspaper and if they didn’t agree with the paper’s politics they could return the issue by the post. Those who retained the issue would be placed on the Subscribers’ List—an early example of what today is called unsolicited supply. Johnson also advised recipients not to keep a copy out of compassion since if necessary he would seek reforms even if they affected “our best friend.”

Johnson pledged that at the end of the year if he was satisfied with himself, he would treat himself and any well-wishers to a bottle of something that would remain nameless.

Politically, Johnson pledged himself to being neither Whig (Reform) or Tory (Conservative). However, it is evident from the newspaper’s coverage of political events that Johnson was an ardent reformer. The newspaper’s account in its first issue of the evolving Canadian political scene provides a fascinating contemporary look into the turbulent period immediately prior to the Rebellions of 1837 when radical reformers took up arms against repressive, non-representative governments in Upper and Lower Canada.

The first issue of the Bytown Independent took place against the backdrop of a change in the leadership of Upper Canada. Sir John Colborne had just been replaced by Sir Francis Bond Head as Lieutenant Governor. Colborne, a military man who had served under the Duke of Wellington during the Napoleonic War, was conservative by nature and served Upper Canada with an unostentatious style. He successively increased the population of Upper Canada through emigration from Britain and instituted a major public works programme to improve communications across the Province. However, while conscious of the need for constitutional reform, Colborne did nothing to address the provincial political grievances. While many moderates approved of his administration, radical reformers resented his treatment of the House of Assembly, the cost of assisting immigrants, and his use of public funds without the support of the legislature.

Johnson comments on Colborne were scathing and were often close to being libelous. He wrote:

“We can speak of Sir John’s administration from our own knowledge—not from rumours afloat; and we do say this of it, that it was the most puny, partial and political Government that ever any Colony was governed by.”

As well, Johnson, who called Colborne “a scanty head,” accused the Lieutenant Governor of interference in the 1832 by-election in Carleton County. He blamed the election of Hamnet Pinney (or Pinhey), a Tory, over George Lyon, a reformer, by Colborne’s appointment of a corrupt and biased returning officer.

In the newspaper’s first issue, Johnson published the first half of a letter of instructions to Sir Francis Bond Head from Lord Glenelg, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in London. (The second half was to appear in the second issue of the Independent.) The instructions refer to the mammoth Seventh Report of the Select Committee, which had been chaired by William Lyon Mackenzie, on the grievances of Upper Canada’s House of Assembly. The chief grievance was the “almost unlimited extent of the patronage of the Crown,” exercised by the Colonial minister and his advisers. Lord Glenelg made it very clear that he did not favour the appointment of public officials by the legislature, or by any form of popular election. He feared that such public officials would not work for the general good and “would be virtually exempt from responsibility.” Far better for the Lieutenant Governor to appoint able men who would not promote “any narrow, exclusive or party design.” Given the explosive contents of Glenelg’s letter, it was astonishing that Head released it to the press.

A lengthy response to Glenelg’s instructions written by William Lyon Mackenzie, which originally appeared in a Toronto newspaper, was also published. Mackenzie wrote that throughout the two Canadas there was a “general feeling of disappointment and regret.” He added:

“If Sir Francis appoints to Executive Council men…known for their ability, integrity, firmness and sincere attachment to reform principles, his path will be smooth and easy…but if His Excellency shall retain in office the avowed enemies of free institutions, men whom the basest governments of England ever knew, have made use of their minions to oppress our country, it will be our duty at once to demand his recall and insist that a government which is in itself the greatest of all grievances be made suitable to our wants.”

Unfortunately, Head went on to alienate reformers—his arrogance and ignorance a disastrous combination. Although Tories won the General Election in June 1836 owing to Head’s appeals of loyalty to the Crown, his actions against reformers led to rebellion. In late 1837, Mackenzie declared himself president of the short-lived Republic of Canada. But the insurrection quickly fizzled. Mackenzie fled to the United States while Head was recalled in disgrace. These events set the stage for the introduction of responsible government under the leadership of moderates such as Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine during the following decade.

In addition to giving a contemporary account of the political struggle between reformers seeking what Americans might call a “government by the people for the people,” and Tories desiring to preserve an autocracy run by the Governor, the Bytown Independent also provides a fascinating window into economic life of early 19th century Canada. During these years, it was unclear whether British North America would use pounds, shillings and pence or dollars and cents as its currency. British and America coins circulated side by side. Canadian banks, which had just began to circulate their own bank notes, issued paper money in both pounds and dollars, sometimes simultaneously in the form of dual denominated notes. This currency ambivalence can be seen by Johnson setting the price of an annual subscription to his newspaper at $4 dollars in one place and at 20 shillings (£1) in another. It wasn’t until 1857 that the Province of Canada (the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada united in 1841) finally chose dollars and cents—economic ties with its U.S. neighbour trumped political and emotional ties with Britain.

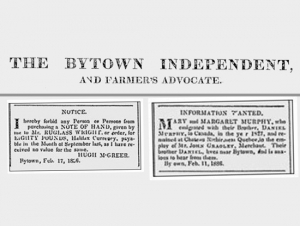

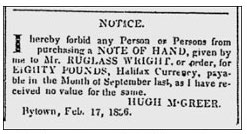

During the early 19th century, promissory notes (notes of hand) were often used as currency. Endorsed on the back, the notes would pass from person to person as money. Ruglass Wright, is probably Ruggles Wright, a son of Philemon Wright who founded Hull. Ruggles, a lumberman like his father, built the first timber slide to transport logs around the Chaudière Falls. In this case, Hugh McGreer is warning potential buyers of the note that he will not pay it if presented.

There is also a reference in the newspaper to “bons”–a form of alternative paper scrip, usually of small denomination issued by merchants which could be used to buy goods in the issuer’s store. Bon stood for “Bon pour,” French for “Good for.”

As well, there is a fascinating reference to “Halifax Currency.” Halifax Currency denoted a way of converting pounds into silver dollars. (It was called Halifax currency after the city where it originated.) One pound, Halifax currency, converted into four silver dollars, or 5 shillings equalled $1. The issuer of a promissory note specified Halifax currency because of the existence of other conversion ratings. For example, in York Currency, which was still in use in parts of Upper Canada in 1836, one silver dollar was worth 8 shillings. To avoid confusion and being short-changed on repayment, it was a sensible precaution to specify the type of currency being used in financial contracts.

Among the advertisements in the newspaper’s first issue are notices from the Post Office listing the times when letters destined for various communities in Upper and Lower Canada had to be received by the Post Office and when letters were delivered at Bytown from these communities. A long list of names of people with mail waiting for them at the Post Office was also provided along with the amount of postage due by them. As these were the days before postage stamps, the recipient of a letter paid the delivery fee. G.W. Baker, the Post Master, warned that unless the amounts were paid by April 5th, the letters would be sent to the dead letter box in Quebec.

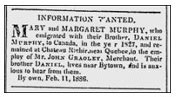

Bytown Independent Personal Ad - 24 February, 1836

The first personal advertisement. One must wonder whether Daniel Murphy ever reconnected with his sister.

In another advertisement, Mr. William Northgraves, a watch and clock maker with an office “nearly opposite the Butcher’s Shambles in Lower Bytown,” announced to Bytown residents that from long experience he had acquired “a perfect knowledge of the practical as well as the theoretical part of the science” and was ready to clean and repair all kinds of watches and clocks. Among other things, he could also repair mathematical and surgical instruments, and make all kinds of fine screws. As a side line, he bought old gold and silver.

Two advertisements were placed in the newspaper by Alexander J. Christie. The first he inserted in his capacity as Secretary of the Ottawa Lumber Association announcing a meeting to be held on March 1st at 10 am at J. Chitty’s Hotel to promote the prosperity of the lumber trade. The second was a request for tenders to clear one hundred acres of land close to Bytown.

Christie must have taken a keen liking in the newspaper. He purchased the The Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate from James Johnson after its second issue. The sale must have surprised the small Bytown community. Christie was a Tory who had helped Hamnet Pinhey win the disputed 1832 Carleton County by-election. Dr. Christie, as he was generally known, was a medical practitioner of uncertain qualifications who had been appointed coroner in 1830 for the Bathurst District in which Bytown was situated. He was also appointed a public notary by Sir John Colborne. Consequently, he represented everything that Johnson had railed against in his newspaper.

Christie relaunched the newspaper a few months later as the Bytown Gazette, and Ottawa and Rideau Advertiser. In his prospectus, Christie claimed that “he comes forward unfettered by a blind adherence to any party.” However, the Gazette’s coverage of political events had a strong Tory bias. After Dr. Christie’s death in 1843, his family held onto the newspaper for a short time and then sold it. During the 1850s, the Gazette was owned by William F. Powell. Subsequently, a Mr. J. McLaurin became the paper’s proprietor. In 1861, McLaurin was charged with practising medicine without a licence. The newspaper appears to have folded about this time.

Bytown regained a local reformist newspaper with the establishment of The Packet in 1843 by William Harris. The Packet was to be renamed The Ottawa Citizen in 1851 and remains the most prominent newspaper in the city to this day.

Sources:

Ballstadt, Carl, 2003. “Christie, Alexander James,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 7. University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed 27 July 2018.

Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate (The), 24 February 1836.

House of Assembly of Upper Canada, 1835, The Seventh Report from the Select Committee on Grievances, chaired by W. L. Mackenzie, Esq., M. Reynolds: Toronto.

Ottawa Citizen, 1851. “The Bytown Gazette And The Solicitor of the Late Corporation,” 26 April.

—————–, 1851. “The Bytown Gazette,” 3 May.

—————-, 1861. “Police Intelligence,” 12 March.

—————-, 1861. “The Liberty of the Press Interfered,” 16 April.

Powell, James, 2005, History of the Canadian Dollar, Bank of Canada.

Wilson, Alan, 2003. “Colborne, John, Baron Seaton,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed 27 July 2018.

Wise, S. W., 1972. “Head, Sir Francis Bond,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, accessed 27 July 2018.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Last Man Hanged in Ottawa

27 March 1946

Shortly after midnight on 27 March 1946, after playing checkers with his guards, a composed Eugène Larment, age 24, was led from the condemned cell in the Carleton County jail on Nicholas Street to the gallows. Hopes for a last minute reprieve had been dashed when his lawyer’s request for an appeal was refused by the Office of the Secretary of State. After Pastor Gordon Porter of the Salvation Army gave the young man spiritual consolation, Larment was hanged by the neck until he was dead. It was 12.32 am. This was the third and last judicial execution carried out in Ottawa’s historic jail. The first was the famous hanging in 1869 of Patrick Whelan, convicted for the murder of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, the father of Confederation struck down by an assassin’s bullet on Sparks Street the previous year. The second was that of William Seabrooke who was executed in early 1933 for slaying Paul-Émile Lavigne, a service-station attendant.

To paraphrase the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, Larment’s death marked the end of a life that was poor, nasty, brutish and short. Born into an impoverished family, Larment’s first brushes with the law came when he was but a child. A frequent truant from public school, Larment was sent to an industrial school in Alfred, Ontario at the tender age of twelve. Most likely it was the St Joseph’s Training School for delinquent boys run by the Christian Brothers from 1933 to the mid-1970s. Like the residential schools for Indigenous children, such training schools, including St Joseph’s, became notorious for the physical, sexual and emotional abuse of their young charges. During the three years he was confined there, Larment apparently received no visitors and no mail from home. He escaped and made his way to Ottawa. Picked up by the authorities, someone reportedly told him that if he confessed to purse snatching, he wouldn’t be returned to the industrial school. Desperate to avoid going back, he did so, and was instead sent to a government reformatory. After he got out on parole, he attended the Kent Street Public School for a short time. With his family described as being “in a bad fix,” he sold junk to scrap dealers to earn a pittance. He also worked as a delivery boy. In 1938, at age 16, he was charged with vagrancy and breaking and entering, and was returned to the reformatory.

Shortly after being released in early 1940, the now eighteen-year old Larment and four friends stole a taxi on McLaren Street in downtown Ottawa and drove to Preston, Ontario where they tied up and robbed two men at gun point at a service station. They netted a meagre $27. Spotted later that night on their return to Ottawa, the young men led police on a wild chase down Bronson Street into LeBreton Flats. Gunshots were exchanged. Turning onto the Chaudière Bridge heading for Hull, the joyriders hit an oncoming car and crashed into a guard rail. Dazed but uninjured, Larment and his companions were taken into custody. They received six-year terms in the Kingston Penitentiary for armed robbery. Larment was released from jail in late September 1945.

The Bytown Inn, Ottawa, postcard, undatedLess than two months after his release Larment, with Albert Henderson and Wilfrid D’Amour staged a daring robbery of the Canadian War Museum on Sussex Street (now Avenue). At about 9 pm on Monday, 22 October 1945, the trio smashed the plate glass of the front door of the museum within a few hundred feet of passersby on the sidewalk, and just a laneway away from the Government of Canada’s Laurentian Terrace girls’ hostel. The bandits made off in a stolen car with three Thompson submachine guns used in World War II, two automatic pistols and four World War I revolvers.

The Bytown Inn, Ottawa, postcard, undatedLess than two months after his release Larment, with Albert Henderson and Wilfrid D’Amour staged a daring robbery of the Canadian War Museum on Sussex Street (now Avenue). At about 9 pm on Monday, 22 October 1945, the trio smashed the plate glass of the front door of the museum within a few hundred feet of passersby on the sidewalk, and just a laneway away from the Government of Canada’s Laurentian Terrace girls’ hostel. The bandits made off in a stolen car with three Thompson submachine guns used in World War II, two automatic pistols and four World War I revolvers.

The following night, a janitor at an O’Connor Street apartment building called the police to report some men acting suspiciously. A “prowler” car manned by Detective Thomas Stoneman and Constable Russell Berndt was dispatched to investigate. The officers found three men loitering outside of the Bytown Inn. The trio split up, with two, later identified as D’Amour and Henderson, walking in opposite directions along O’Connor Street. Detective Stoneman approached the middle man who had remained between the two canopied entrances of the Inn. “I want to talk to you,” the officer said after he got out of the driver’s side of the car. “What do you want?” replied a man in a khaki trench coat. Without warning, the man pulled a gun from his pocket and fired at Stoneman from a distance of only six feet. Stoneman was struck in the chest and fell to the ground grievously wounded.

His partner, Constable Berndt, who had just returned to the police force after 3 ½ years in the navy, ducked when the gunman subsequently aimed at him. Trading shots, the bandit fled through a maze of laneways and alleys, pursued by Berndt who disconcerting found himself followed by D’Amour. Fortunately, another police cruiser arrived on the scene. Constables Thomas Walsh and John Hardon joined the chase for Stoneman’s assailant, while Flight Lieutenant Appleby, a decorated pilot who had accompanied the police officers, tackled D’Amour. Meanwhile, the shooter, Eugène Larment, who had run out of ammunition, was chased into the arms of beat policeman, Constable René Grenville, at the corner of Metcalfe and Slater Streets. The third man of the trio, Albert Henderson, managed to evade immediate capture but was picked up at his home on Albert Street a few hours later. Back at Larment’s family home on Wellington Street and in an abandoned building next door, police discovered the missing weapons stolen from the War Museum.

Initially, the men were charged with attempted murder. But the charges were upgraded to murder when Detective Stoneman died a few days later. The fifteen-year veteran policeman with the Ottawa Police Force, aged 37, born in Mortlach Saskatchewan, left a wife Lois (Cleary) and one-year old twins, Richard Thomas and Jill Lois. Stoneman was accorded a civic funeral. Uniformed policemen from the Ottawa and Hull municipal police, the RCMP, the Ontario and Quebec Provincial Police Forces, the RCAF service police and the naval shore patrol marched in the funeral cortege. The slain policeman was buried in the Beechwood Cemetery.

Even while in jail, the charges against Larment, D’Amour and Henderson continued to mount. In early January, the threesome tried to break out of the country jail. Before being recaptured, they brutally beat up Percy Hyndman, a prison guard. A blow to the head from a heavy broom opened a nasty gash in Hyndman’s scalp requiring five stiches to close.

The trial of the trio for the murder of Detective Stoneman began in mid-January 1946 in front of Justice F. H. Barlow of the Ontario High Court. Deputy Attorney General Cecil L. Snyder, who had an outstanding record of 37 convictions in 38 murder cases, was the special Crown prosecutor. For the defence was lawyer W. Edward Haughton, K.C. who represented the trio pro bono; there was no legal aid at this time. The trial lasted roughly a week. Throughout the proceedings the courtroom’s hard wooden benches were packed with people eager to witness the unfolding drama.

Snyder, the Crown prosecutor, quickly established that the gun that fired the fatal bullet was a revolver stolen in the War Museum heist. There was also no doubt that Larment was the shooter. Larment admitted to firing the weapon “from the hip” in two statements that he made to the police, the first, hours after being apprehended, and the second, a couple of days later. One of the jurors, Thomas Bradley, worried about police procedures in obtaining these statements, was permitted by Justice Barlow to question the police witness. Bradley enquired whether Larment had been asked if he wanted a lawyer before he made his statements. The detective answered no, though he added that Larment had been free to ask for one. Apparently, the detective had pursued standard Canadian police procedures of the time. Justice Barlow ruled that the statements were admissible in court, saying he was satisfied they had been obtained “in the proper manner.”