Super User

The Champagne Bank Robber

27 October 1958

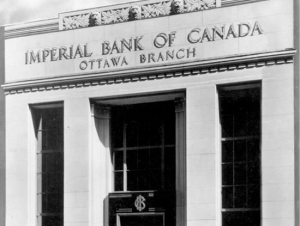

When Mr W.W. Pegg, manager of the Imperial Bank of Canada’s main Ottawa branch at 62 Sparks Street, arrived at work on Monday, 27 October 1958, he had no idea that he was about to experience the worst day of his long and successful career. Entering the classic, Temple-style, granite and sandstone building, his thoughts must have undoubtedly been on the Slater Street gas main explosion that had rocked Ottawa’s downtown core just two days earlier, injuring scores, demolishing buildings, and shattering store fronts and glass windows in a several block area from Sparks Street to Somerset Street. But on opening the bank’s vault for the start of the day’s business, all thoughts about the explosion would have been forgotten by the sight that confronted him, or, more correctly by what he didn’t see. The cash reserves of the bank were gone. Also missing, were funds transferred to his branch from smaller Imperial bank branches across the city the previous week. How the audacious theft was committed was not immediately apparent. There was no signs of forced entry. It took head office auditors days to determine the precise amount of the shortfall—an astonishing $260,958 (equivalent to $2.2 million today), the largest theft ever from an Ottawa bank.

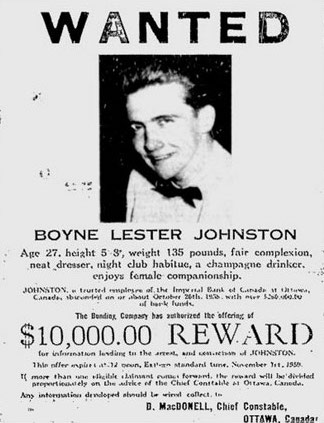

Suspicion immediately fell on Boyne Lester Johnson, Pegg’s 27-year old, trusted, chief teller. Johnson, a Renfrew native, was a seven-year veteran of the Imperial Bank, having joined the financial institution out of high school. Among his duties were handling the cash deposits brought in from other Imperial branches. Consequently, a large volume of money routinely passed through his hands. Although everything had appeared normal when he had left work with other bank employees the previous Friday, he had failed to show up Monday morning.

When police arrived at Johnson’s home, apartment #20 at 350 Chapel Street in Sandy Hill, there was no sign of him, or his wife Bernice. A search revealed a large sum of cash though there was no way of knowing whether the money was part of the missing bank funds; the bank had no record of the serial numbers of the stolen notes. The Johnsons’ family car was in the basement parking lot, a .22 calibre hunting rifle, hunting clothes, and maps were found in its trunk. The building’s caretaker told the police that he had last seen Boyne Johnson on Sunday morning when the young man had awoken him at 8.30am to ask to be let into his apartment. Johnson had told him that he had forgotten his key after going to church with his wife. The superintendent thought this was odd as Boyne was dressed in old clothes rather than his Sunday best. Police immediately issued a warrant for his arrest, alerting law enforcement agencies across the country, as well as the FBI in the United States. Rail stations, airports, car rental agencies, and customs posts were also advised to be on the watch for Boyne Lester Johnson.

Johnson Wanted Poster released by Ottawa Police and circulated throughout North AmericaWhile Ottawa police were trying to track down Boyne, Bernice Johnson was becoming frantic with worry. On the Saturday, the couple had driven to Renfrew to visit their mothers, Mrs Mary Johnson and Mrs Julia Narlock who lived in the town. They had supper that evening with the two parents in a Cobden restaurant. Everything seemed normal. The couple spent the night at the home of Bernice’s mother. The next day, Boyne had risen early, telling his wife that he was going hunting close to the Renfrew golf course. She last saw him at 6.30 Sunday morning. He never returned. On Monday morning, she and a friend began searching the Renfrew area for her missing husband. Having no luck, and fearing that some serious had happened to him, she turned to the Renfrew police department for assistance. She was shocked to find out that her husband had become the subject of a nation-wide alert.

Johnson Wanted Poster released by Ottawa Police and circulated throughout North AmericaWhile Ottawa police were trying to track down Boyne, Bernice Johnson was becoming frantic with worry. On the Saturday, the couple had driven to Renfrew to visit their mothers, Mrs Mary Johnson and Mrs Julia Narlock who lived in the town. They had supper that evening with the two parents in a Cobden restaurant. Everything seemed normal. The couple spent the night at the home of Bernice’s mother. The next day, Boyne had risen early, telling his wife that he was going hunting close to the Renfrew golf course. She last saw him at 6.30 Sunday morning. He never returned. On Monday morning, she and a friend began searching the Renfrew area for her missing husband. Having no luck, and fearing that some serious had happened to him, she turned to the Renfrew police department for assistance. She was shocked to find out that her husband had become the subject of a nation-wide alert.

Johnson’s trail went cold. There were few clues to his whereabouts. Police speculated that he was still in the vicinity, but admitted they really didn’t know. To help their inquiries, the Ottawa police and RCMP issued a detailed “wanted” poster with a $10,000 reward for information leading to his arrest and conviction. He was described as age 27, height 5’ 8,” weight 135 pounds, with a fair complexion. Also noted was that he was a neat dresser, frequented night clubs, and had a penchant for champagne and the ladies. The poster went out to police stations and post offices across North America. Tips started to come in. A Trans-Canada Airways (TCA) stewardess thought she had spotted Johnson on a flight from Ottawa to Montreal. On 5 November, Montreal police were sent “scurrying” on receiving a phone call from a man who identified himself as Inspector Osborne, a vacationing Ontario Provincial policeman. He called Montreal police headquarters telling them that he had captured Johnson, and sought aid to bring him in. He also claimed to have the money in an airline carry-on bag. It was a hoax. No Inspector Osborne worked for the OPP.

The big break came on Monday, 10 November when Geneva Flowers, a waitress at Chez Paree, a Denver, Colorado night club, recognized Johnson from his wanted poster shown to her by a friend in the Denver police department. Another server, Ormonde Wynn, had spotted Johnson sipping champagne sitting at the bar. The Denver police were called, arresting Johnson without a fuss. He took the policemen to his YMCA room where they found a suitcase crammed with more than $233,000 in mostly Canadian cash. He also told them that on arriving in Denver he had bought a $4,150 sports car, and had planned to go skiing in the mountains. He said that he always wanted to know what it was like to have lots of money. He admitted that he knew he would eventually be caught, and was glad it was all over. He had wanted to experience the “have fun while you can principle.” Denver policemen said that the highly detailed wanted poster circulated by Canadian police that had highlighted Johnson’s love of champagne was responsible for his capture.

Under police questioning, Johnson freely explained how he robbed the bank, and his movements over the previous two weeks. Through the day on Friday, 24 October, he had removed cash from the vault, secreting the money in accessible spots around the bank. At some point, exactly when is not clear, he converted $7,000 into U.S. currency at another Ottawa bank. That night, he returned to the Imperial Bank’s Sparks Street branch, letting himself in using the key with which he had been entrusted as chief teller. He then retrieved the money from their caches, filled a suitcase, and left via a rear laneway exit to his car. There were no witnesses. Returning home with the suitcase in the trunk, he calmly drove with his wife to Renfrew the following day, the suitcase still in the back of the car. On Sunday morning, instead of hunting, he returned to Ottawa, stopping off at his apartment, where he left some money for his wife. He then flew to Windsor, Ontario. At the Windsor airport, he stored the cash-stuffed suitcase in a locker, and took a taxi to the Detroit airport. Pretending to have accidently forgotten his suitcase, he persuaded a Detroit taxi driver to go to the Windsor airport and fetch it for him. Incredibly, the driver agreed to do so, passing through US customs without incident. Johnson gave him a $20 tip for his trouble. From Detroit, he flew to Los Angeles, before going to Salt Lake City, Twin Falls, Idaho, Cheyenne Wisconsin, and finally Denver, where the law finally caught up with him. While in Cheyenne, Johnson, feeling blue, had telephoned a friend, Gerald Cotie, the third assistant accountant at the Imperial Bank branch. Cotie had urged Johnson to give himself up, but without success.

With Johnson waiving an extradition hearing, two Ottawa police officers, Inspector Ab Cavan and Detective Gordon Lowry, went to Denver on November 11 to officially identify him, and to return him to Ottawa. With a stop at Malton Airport in Toronto, Johnson arrived at Uplands Airport, Ottawa, accompanied by the two officers, on a regular TCA flight, at shortly before 10pm on 14 November, three weeks after the heist. On arriving in the city, he politely thanked the two detectives. Wearing a suede windbreaker, dark grey trousers, and running shoes, Johnson walked briskly down the steps to be greeted by flashing light bulbs and television cameras. More than 300 spectators were on hand to meet his plane. When asked why he did it by a Citizen reporter, Johnson replied “It’s hard to explain. I guess it was the climax to a lot of personal trouble.” He also told journalists that “It’s nice to have met you. But when you write this, don’t say ‘Go west, young man!’ It just doesn’t work out.”

On the following Monday, he was officially charged, and was remanded into custody by Magistrate Glenn E. Strike. No plea was entered, and no bail was set. In the crowded court room was his wife, Bernice. Johnson, who did not speak at the hearing, was represented by John Dunlop; James Maloney, QC, Member of Parliament for Renfrew, was retained as Johnson’s defence counsel. A month later, Johnson plead guilty, and was convicted. In court, it was revealed that all $260,958 that he had stolen from the Imperial Bank had been returned. The bulk of the money was discovered by Denver police in Johnson’s YMCA room. A further $5,000 was recovered from his Chapel Street apartment. He had spent only $12,050. Johnson’s father, Hartzell Johnson, made up the shortfall. His father also told the judge that he was planning to start a business in another city, and would offer Boyne a job on his release from jail. Wife Bernice also said she would stand by her man, and wait for him.

During his short hearing, police officers testified that Boyne had been “a model prisoner,” and it seemed that “he was glad to have been caught.” One testified that Johnson seemed to have been trying to run away from himself. Defence counsel argued that Johnson was “not really a criminal.” The prosecuting Crown attorney, Raoul Mercier, countered that it was important for society to be protected from thefts by trusted employees.

On Thursday 18 December, in front of several Johnson family members, Judge Strike pronounced sentence. The magistrate said that he had little sympathy for Boyne. His was a very serious crime involving a very large sum of money, and that Boyne had been disloyal to both his employer and his family. A pale but composed Boyne Johnson received his sentence—four years in the Kingston Penitentiary.

Sources:

McGuire, C.R., A History of 62 Sparks Street, Ian Kimmerly Stamps.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1958. “Ottawa Bank Teller Hunted After $250,000 Cash Taken, Sparks Street Branch Looted,” 27 October.

————————, 1958. “‘Tip’ on Man Hunt ‘Phony,’” 6 November.

————————, 1958. “Boyne Johnson Nabbed In Denver,” 11 November.

————————, 1958. “Led To Arrest,” 11 November.

————————, 1958. “Give The Mechanics Of Returning Banker,” 12 November.

————————, 1958. “‘Why?’ Hard To Explain,” 15 November.

————————, 1958. “Remanded, Boyne Silent After Charge,” 17 November.

————————, 1958. “All Fund Returned, Teller Admits $260,000 Robbery,” 10 December.

————————, 1958. “‘You Were Disloyal’—Magistrate, Four Years In Prison For Johnson,” 18 December.

————————, 2015. “Mover and shakers in capital’s foodie scene,” 26 April.

Images:

Imperial Bank of Canada, 62 Sparks Street, Ottawa.

Wanted Poster, The Ottawa Citizen, 7 November, 1958

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Nile Voyageurs

13 September 1884

Like today, the Middle East during the late nineteenth century experienced an Islamist uprising, kindled by a revival of religious fervour, oppressive political regimes, and resentment towards growing Western influence in the region. In 1881, a Sudanese fanatic, Muhammad Ahmad, proclaimed he was the Mahdi, the prophesied redeemer of Islam, with a mission to revitalize the Faith, restore unity to the Muslim community, and prepare for Judgement Day. He then started a military campaign against the Egyptian-controlled, Sudanese government. Needless to say, this did not go over well with the Khedive, or viceroy, of Egypt. Ostensibly a subject of the Ottoman sultan in Constantinople, the semi-autonomous Khedive, Tewfik Pasha, owed his throne thanks largely to Britain who had come to his aid when a military coup, which almost toppled his regime, threatened British control of the Suez Canal, the Empire’s vital link to India.

But British Prime Minister Gladstone, concerned about the cost of providing military aid, was unwilling to help the Khedive suppress the Mahdi. Instead his government advised Tewfik Pasha to evacuate his soldiers and civilians from the Sudan, and form a defensive perimeter on the Egyptian-Sudanese border. This the Khedive agreed to do. The British government asked Major-General “Chinese” Gordon to go to Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, to facilitate the Egyptian withdrawal.

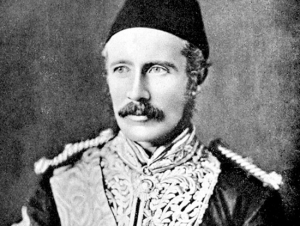

On the surface Gordon appeared ideal for the job. A deeply religious man, Gordon was a veteran of many campaigns, including the Crimean War. In the 1860s, he had served with distinction in China, rising to command with British approval the Imperial Chinese forces that suppressed the Taiping Rebellion–hence his nickname “Chinese.” Subsequently, with the support of the British government, he had worked for the Egyptian Khedive, and had for a time been his Governor General of Sudan. During this interlude Gordon suppressed the Sudanese slave trade.

However, according to the senior British representative in Cairo, “a more unfortunate choice could scarcely have been made that that of General Gordon” who he described as “hot-headed, impulsive, and swayed by his emotions.” Gordon arrived in Khartoum from London in February 1884, after he had stopped off in Cairo and had been reappointed Sudan’s governor general by the Khedive. But after sending a few hundred sick Egyptian soldiers, women and children down the Nile to safety, evacuation plans were abandoned. Convinced that the Mahdi threatened Egyptian and British interests, and had to be stopped, Gordon put the Egyptian garrison and Sudanese civilians to work building earthwork defences to repell the Islamist forces. By March 1884, Khartoum was besieged by the Mahdi’s army of some 50,000 men. Gordon appealed home for aid to a reluctant government that didn’t want to get involved.

Pressured by British public opinion that had been stirred by an imperialist press that portrayed Gordon as a dashing and romantic figure, Gladstone’s government buckled. A relief force under the command of General Garnet Wolseley was dispatched to Khartoum in late 1884. Wolseley was as renowned as Gordon, having served in India, China, and Egypt. Parenthetically, he was also the army officer caracaturized by Gilbert and Sullivan in the song “I am the model of a modern Major-General,” in their play Pirates of Penzance.

Most importantly for this story, Wolseley had campaigned in Canada, having commanded the Red River Expedition in 1870 that put down the rebellion of Louis Riel in what became Manitoba. Remembering the prowess of native and Métis canoers, Wolseley contacted Canada’s Governor General, Lord Lansdowne, through the Colonial Office asking for 300 voyageurs from Caughnawaga [Kahnawake], St Regis [Akwesasne] and Manitoba. Their non-combatant, six-month tour of duty was to act as steersmen for his Nile Expedition, transporting soldiers down the Nile to Khartoum. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald agreed to the request on the proviso that all expenses would be paid by the British government.

The Ottawa Contingent of the Canadian Voyageurs in front of the Parliament Buildings, Ottawa, 1884.

The Ottawa Contingent of the Canadian Voyageurs in front of the Parliament Buildings, Ottawa, 1884.

Library and Archives Canada, Mikan No. 3623770Despite insistence from the Colonial Office that the British Army wanted native voyageurs, the Canadian government argued that the day of the voyageur was over, and that white raftsmen who drove logs down the Ottawa River had better navigational skills that native boatsmen. Of the 386 officers and men who volunteered for the Nile Expedition, roughly half were hired from the lumber shanty towns of Ottawa-Hull. Another 56 Mohawks came from the Caughnawaga and St Regis areas. A further 92 men heeded the call from the Winnipeg area, of whom roughly one third were Manitoba Ojibwas, led by Chief William Prince. Many were veterans of the Red River campaign. The remainder came from Trois Rivières, Sherbrooke and Peterborough. Roughly half of the men spoke French, one-third English, with the remainder speaking native languages. The majority of the volunteers were experienced boatsmen, though according to one account about a dozen from Winnipeg appeared “to be more at home driving a quill [pen] than handling an oar.”

The appeal for volunteers met widespread public support. Imperialist sentiment in Canada was strong. There was a keen desire, especially among English-speaking Canadians, to prove to Britain that Canada was not just some far-flung outpost but was willing to do its part for Queen and Empire.

It took less than a month after Wolseley’s appeal to assemble the Canadian Nile contingent under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Denison of the Governor General’s Body Guard, a unit of the Canadian militia. Denison, only 37 years of age, was a veteran of the Red River Expedition. He was also well known to Wolseley, having been his aide-de-camp during that campaign. Other senior officers included Major William Kennedy of the 90th Winnipeg Rifles (another Red River veteran), Captain Telmont Aumond of the Governor General’s Foot Guards, and Captain Alexander MacRae of London’s 7th Battalion. Surgeon-Major John Neilson (another Red River veteran) provided medical care, while Abbé Arthur Bouchard, who had been a missionary in Sudan, accompanied the contingent as chaplain.

The Ottawa contingent assembled on Saturday, 13 September 1884 at the office of T.J. Lambert, the recruiting agent, on Wellington Street at 11am. The sidewalk in front of the office building quickly became so crowded with men and well-wishers that the throng spilled onto the grounds of Parliament Hill across the street. There, a photographer from Notman’s studio took photographs of the men in front of the main entrance to the Centre Block. Also present to entertain the crowd and to provide a fitting send-off to the Ottawa volunteers was the band of the Governor General’s Foot Guards that played a selection of popular tunes, including En roulant ma boule roulant, Home Sweet Home, The Girl I Left Behind, and Auld Lang Syne. At about noon, the men fell in and marched to the Union Depot in LeBreton Flats. A large crowd assembled at the train station to see them off, including most of the area’s lumber mill workers. A special CPR train took the men to Montreal where they joined up with the other contingents, and boarded the 2,500 ton steamer Ocean King for Alexandria.

The expedition was well organized. Each volunteer received a rigorous medical exam. Pay was set at $40 per month plus rations. Each man also received a $2.25 per day allowance from the date of their engagement to their departure date, as well as free passage to and from their destination. Additionally, the volunteers each received a kit consisting of a blanket, towel, smock, home-spun trousers and a jersey, woolen undershirt and drawers, two pairs of socks, a pair of knee-high moccasins, a flannel belt, a grey, wide-brim, soft hat, a canvas bag, and a tumpline to help carry things. Oddly, an optician from London, England offered to supply 450 pairs of spectacles free of charge. A Montreal evangelical group also provided a bible to every man. The men were given an advance of $10 and could make arrangements for any part of their pay to be sent to another person. Most arranged for three quarters of their pay to be sent to wives or parents. In addition to transporting the men, the Ocean King also shipped a birch bark canoe for the personal use of General Wolseley on the Nile.

Needless to say given the background of the men, a potent mixture of French Canadians, Irish, Scots, English, Métis and native peoples, most used to hard drinking and rough living in the lumber camps and the bush, it was a rowdy bunch. A reporter from the Montreal Gazette recounted a brawl that broke out aboard ship on the day the volunteers arrived from Ottawa after “a French Canadian struck an Indian.” He commented that was nothing to distinguish between the so-called “quiet and orderly Winnipeggers from the Ottawaites in the melee.” They were undoubtedly brought to heel by Captains Aumont and MacRae who were described as “two of the toughest customers.” On the day of departure, Sunday 14 September, the Governor General and Lady Lansdowne, and the Minister of the Militia and Defence, Adolphe-Philippe Caron, saw the Nile Voyageurs off to Egypt. Although the Ocean King had apparently been well provisioned, the Governor General sent beans, cabbages and apples to supplement the men’s rations.

The Canadian contingent arrived in Alexandria in early October, and quickly made their way up the Nile on a steamer to the main British base at Wadi Halfa. There, the voyageurs were divided into detachments and located at the six cataracts, or rapids, that needed to be traversed before the British forces could reach Khartoum. The boats, converted Royal Navy whalers, were 32 feet long, with a 7 foot beam, and a depth of 3 ½ feet. The voyageurs didn’t think much of them. The complained that they were made of inferior wood and had keels; flat bottoms would have been better given the circumstances. Despite the boats’ shortcomings, the men provided invaluable service to the British relief force, working long, grueling days in the desert heat to transport the troops through the treacherous Nile rapids. Despite their success, some British officers were shocked by the Canadians’ lack of discipline and deference to authority. This undoubtedly was due to the fact that the men were civilians, not soldiers, even if they were led by military men.

In early 1885, knowing that Gordon could not hold out much longer, Wolseley split his forces. While one detachment continued to make its way down the Nile to Khartoum, another was sent on a desperate trek across the desert to cut off the “Great Bend” in the river. By this point the number of Canadians supporting the mission had been greatly reduced. With their six-month tour of duty about to expire, most had started home in order to make it back for the logging season; a fifty percent increase in pay was insufficient inducement to stay. A rump of about 75 men re-enlisted to assist the British forces down the remainder of the Nile to Khartoum. Fortunately, the rapids were less severe by this point, and with a smaller number of troops to transport the diminished Canadian contingent was equal to the task.

Wolseley’s Nile Expedition ended in failure. The British relief forces arrived in Khartoum two days after the Mahdi’s forces had stormed Khartoum. General Gordon had been killed in the fighting, his head cut off and sent to the Mahdi, reportedly against the Muslim leader’s wishes. Apparently, the Mahdi and Gordon had great respect for each other, with each trying to convert the other. As for the besieged residents of Khartoum, some 10,000 soldiers and civilians were massacred. After successfully engaging a force of Sudanese fighters at nearby Kirbekan, the British relief column was ordered back to Egypt, with the Canadians again assisting the British forces through the Nile rapids, this time down river.

The bulk of the Nile Voyageurs returned to Canada through Halifax in early March 1885 aboard the Allan steamer the Hanoverian. The Ottawa contingent arrived home by train on 7 March. Much of the city’s population came out to greet them. The Frontenac Snowshoe Club lined the train platform to welcome them. After greeting their friends and families, the men paraded downtown led by two musical bands. A celebratory lunch followed. Ottawa residents eagerly snapped up pictures of their heroes. Twenty-five cents bought engravings of General Gordon or General Wolseley, while one dollar purchased a picture of the Nile contingent. The British Parliament later passed a motion of thanks to the Canadian voyageurs for their contribution to the Nile Expedition.

Of the 386 Nile voyageurs, twelve perished from drowning, disease, or accident on the expedition. Of these, M. Brennan and William Doyle were from Ottawa. Today, the Nile Voyageurs, Canada’s first foray on the international scene, have been largely forgotten. A memorial plaque to the Voyageurs was erected in 1966 in Ottawa at Kichissippi Lookout close to the Champlain Bridge. The names of the Nile voyageurs who perished are also recorded in the South Africa-Nile Expedition Book of Remebrance located in the Memorial Chamber in the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill.

Sources:

Boileau, John, 2004. “Voyagers on the Nile,” Legion Magazine, 1 January.

Canada, Government of, 2011. “The Nile Expedition, 1884-85,” Canadian Military History Gateway.

Daily Citizen, (The), 1884. “Nile Boatman,” Ottawa, 13 September.

————————, “Off to Egypt,” 15 September.

————————, 1885. “Safe Voyage,” 5 March.

Gazette, (The), 1884. “The Canadian Contingent,” Montreal, 15 September.

————————. “Off for Alexandria,” 16 September.

———————–. “Home Again,” 5 March.

MacLaren, Roy, 1978. Canadians on the Nile, 1882-1898, Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Michel, Anthony, 2004. “To Represent the Country in Egypt: Aboriginality, Britishness, Anglophone Canadian Identities, and the Nile Voyageur Contingent, 1884-1885,” Social History.

Plummer, Kevin, 2015. “Ascending the Nile,” Torontoist, 21 February.

Images:

The Canadian Voyageurs in front of the Parliament Buildings, Ottawa, 1884, author unknown, Library and Archives Canada, MIKAN No. 3623770.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

An Assassination in Ottawa

7 April, 1868

Back in April, 1868 the only murder of a federal MP happened right here on Sparks Street! It was, in fact , the murder of a “Father of Confederation “as the individual had played an active part in the Constitutional conference at Charlottetown P.E.I in 1864 that brought us the British North America Act of 1867. Charlottetown was the original conference concerned with the foundation of Canada as a nation. The murdered man's name was Thomas D'Arcy McGee, of Irish extraction. The man who was convicted of murdering him, Patrick Whelan, the last individual subject to a public hanging in Canada was also an Irishman and a member of the Fenian Brotherhood.

The Fenian brotherhood was dedicated to freeing Ireland from British rule and were the last official invaders of Canada in 1866 and 1870. The presence of the Fenians, who were largely US Civil War veterans, probably added extra pressure to the idea of forming the Canadian nation. Their aim was to conquer Canada and then trade it back to Britain for Irish freedom. McGee had begun his political career as a strong proponent of Irish freedom, but became a stronger proponent of Canadian Confederation and argued against Fenian ambitions, which may have convinced the Fenians that he was a traitor to their cause. In any event, McGee was shot with a bullet to the back of the head outside his lodgings at 142 Sparks Street on April 7, 1868. He was retuning late from the House of Commons and there was no witness to his shooting.

McGee was born in Ireland in 1825 and first came to Canada in 1857 after a career as a journalist and political activist both in Ireland and the United States. He argued vigorously for Irish freedom, but was opposed to the measures expressed by the Fenian brotherhood He rose in Canadian politics and, at the time of the Charlottetown Conference was Minister of Agriculture in John A. Macdonald's government. He was a fiery orator in th e days when oratory was an art form. There are several pictures of McGee on pages 372 and 376 in Charlotte Gray's excellent book The Museum called Canada. There is also a pamphlet available from the Bytown Museum that fully discusses McGee's career.

Needless to say, McGee's death caused an uproar in local circles. Extreme pressure was exerted on the local police authorities to find arrest and punish the perpetrator. Suspicion fell on a local Fenian, Patrick Whelan and Gray's book has examples of the wanted posters offering substantial rewards for Whelan's capture, even though there was little evidence available to connect him to the crime. He was eventually captured and incarcerated in the Ottawa gaol. The story of Whelan's trial, conviction and execution is a story in itself and will appear here in the not too distant future.

McGee's funeral in Montreal was a large one with literally thousands of people lining the streets. Special testimonial dinners were held in Ottawa and Montreal, speeches were made and the threat of the Fenians was underscored. In those days, it was usual to make a plaster cast of a famous dead person's face so that people would remember what the deceased looked like. This was especiallytrue if no painting existed. While photography was rapidly developing, it was not yet to the level of popularity it would later enjoy. One problem existed—McGee had been shot in the back of the head and there probably was extreme facial damage. Therefore, to commemorate McGee's oratorical skillsa plaster cast was made of his hand with which he used to gesticulate while making his speeches! A picture of this cast appears in Gray's book also but you only have to visit the Bytown Museum to see the real thing. The Museum has a section devoted to the memory of McGee and the death cast is there together with other mementos. For a while, the Museum also exhibited the gun that was used to shoot McGee. This gun belonged to a descendant of the Judge that tried Whelan, but was recently acquired by a National Museum which loaned it to the Bytown for an exhibit.

The next time you are walking down the Sparks Street mall, between Metcalfe and O'Connor look for the plaque that marks the spot where McGee was shot.

Who says. Ottawa doesn't have stories to tell?

Cliff Scott, an Ottawa resident since 1954 and a former history lecturer at the University of Ottawa (UOttawa), he also served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Public Service of Canada.

Since 1992, he has been active in the volunteer sector and has held executive positions with The Historical Society of Ottawa, the Friends of

the Farm and the Council of Heritage Organizations in Ottawa. He also inaugurated the Historica Heritage Fair in Ottawa and still serves on its organizing committee.

Patrick Whelan

11 February, 1869

On February 11, 1869 in the Carleton county gaol, Patrick James Whelan was hanged for the murder of Thomas D'Arcy McGee. He went to the gallows protesting his innocence and, without all the forensic evidence TV keeps showing ,there is no way we can ever be sure he was truly guilty. There are some who believe he was innocent and that his conviction was rushed to show the efficiency of the police, prosecutors and the government of the day. The murder of McGee had taken place the previous April and Whelan was arrested within 20 hours The basis of his conviction was his possession of a revolver of the same calibre as the murder weapon, stories that he was a Fenian and the testimony of a person who had shared his cell in the gaol who swore Whelan had confessed to him that he, Whelan, had indeed carried out the shooting. This evidence was enough to convict Whelan and led to the last public hanging in Canada, right here in staid old Ottawa. A Wikipedia article states that five thousand people attended the event. Whelan was buried on the grounds of the gaol, but no one knows exactly where. Remains were discovered some years later, but could not be confirmed as those of Whelan, Whelan's ghost is still said to haunt the gaol, still protesting his innocence. One fact is that public hangings were banned in Canada about five months after the execution.

Whelan was of Irish extraction having been born in County Galway c. 1840. He was a tailor by occupation and apparently considered good at it. He came to Ottawa from Montreal in 1867 and was employed by the firm of Peter Eagleson. The Canadian on line encyclopedia describes him as "skilled at this trade, fond of horses, shooting, dancing and drink". This would describe my own Irish ancestors and many current Irish Canadians! While he was an apprentice tailor in Quebec City after 1865, he volunteered for military duty to oppose Fenian invasions of Canada. He married Bridget Boyle in 1867 and made his home in Ottawa. Perhaps a dedicated researcher can find where his residence in Ottawa was, or his immigration record. Ship landing records are on file at the National Library and Archives from 1865 on. Names and residences are in the City directories.

To the Canada of 1866-67 the Fenians were a scary commodity. Mostly Irish expatriates and many of them hardened veterans of the US Civil War (both Union and Confederate) they were dedicated to conquering Canada to hold as ransom for Ireland. They invaded Canada in 1866 and defeated a hastily organized force of militia and some British regulars at Lime Ridge near Fort Erie. They hoped for an Irish uprising in Canada, and when that did not occur they retreated to the United States where they continued to agitate. Another attempt was made south of Montreal in 1870. All the details can be found in Senior's book The Last Invasion of Canada for those interested.

Whelan was said to be sympathetic to this group, but there is little, if any, hard evidence to go on. Why did he volunteer to fight the Fenians in 1866? There are several facts that suggest he may have been a scapegoat. There was intense political interest in his trial as evidenced by the fact that the Prime Minister, Sir John A. Macdonald sat beside the presiding judge during the initial trial. The judge was William Richards who was appointed to the Court of Queen's Bench after that trial just in time to preside over the appeal of Whelan's death sentence. The vote to reject the appeal was 2-1, with Richards casting the deciding vote. While historians are not supposed to use today's standards to make judgments on pat events, there seems to be grounds for suspicion, at least.

A play, “Blood on the Moon” has been written that queries the conviction and a song "The Hangman's Eyes" has been composed about Whelan's execution A little known historical fact is that real Fenians, who invaded Canada were originally sentenced to death, then the sentence was commuted to life in prison. All of the individuals concerned were out of prison within a decade after the events, except for one individual who died of natural causes during his incarceration A review of government records indicates that a question as to what correspondence there had been about these prisoners was not answered in the House on the recommendation of a House review committee. If this kind of generous treatment was accorded to the real Fenians, why not Whelan? An answer to that question eludes us to this day.

Cliff Scott, an Ottawa resident since 1954 and a former history lecturer at the University of Ottawa (UOttawa), he also served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Public Service of Canada.

Since 1992, he has been active in the volunteer sector and has held executive positions with The Historical Society of Ottawa, the Friends of the Farm and the Council of Heritage Organizations in Ottawa. He also inaugurated the Historica Heritage Fair in Ottawa and still serves on its organizing committee.

John Rudolphus Booth

12 February, 1924

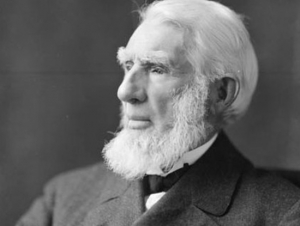

Once the Rideau Canal was finished in 1832, Bytown had to find a new economic base. Surrounded by trees and with England crying out for lumber, it was only natural that the timber trade, in different phases, would become a staple of the new town situated on a major transportation route. One of the giants of the lumber business was J. R Booth, born in Waterloo, Quebec, who arrived in Ottawa in 1857 and lived here until his death on Dec. 8, 1925.

There are many anecdotes about Booth and his various idiosyncrasies but a good, recent book is J. R. Trinnell's “J. R. Booth—The Life and Times of an Ottawa Lumber King” It is a mixture of anecdotes and business statistics and a chronological list of happenings in Booth's long life In that life, Booth built and operated three railways in Ontario, was burned out a number of times, but always rebuilt, married off one of his grand daughters to a Danish prince and lived almost 99 years, outliving five of his eight children in the process.

"Booth was known as a frugal man who didn't put on airs, despite his wealth and position."

Booth was known as a frugal man who didn't put on airs, despite his wealth and position. One anecdote concerns a particularly self satisfied salesperson who cane to meet Booth one morning for a business meeting. Spying a scruffy looking individual standing outside the office, he offered him a dime to carry his sample case upstairs to Mr. Booth's office. The man obliged and, when asked where Mr. Booth was, said “You're looking at him! ” Where's my dime? ” This is a story from my wife's grandfather who knew Booth in the early part of the last century. Another well known anecdote concerns the time Booth was criticized by a driver for only giving a ten cent tip. The rationale was tha t Booth's son always gave a quarter. Booth replied, gruffly “That's alright, the boy has a rich father, but I was an orphan! ”.

Booth came to the town now known as Ottawa in 1857 and, many years later, shortly before his death was asked about his earliest memories of the town. He responded by commenting on the smell of the place. Thomas Anglin, a Montreal MP also commented in Hansard about the smell and dirt of “Ourtown” in the early 1880's. One of my own recollections from when I first arrived in Ottawa in 1954 was the overwhelming smell of the pulp mills across the river early one April morning While the closing of the pulp mills was an economic disaster for some, it did improve air quality! Before the famous fire of April 26, 1900, Booth lived at the corner of Wellington and Preston streets, only a block or two from his mill. His neighbours on Wellington (also known as Richmond Road at the time) were the Salvation Army Rescue home and the Victoria Brewery. Further up Wellington were a “lying in” hospital, a Mr. Frank Morgan and the Victoria Hotel. All were destroyed in the fire. Mr. Booth then built his home on Metcalfe St., near Somerset which later became the Laurentian Club.

"The big event of the 1924 social season was the wedding of Booth's grand-daughter Lois, to Prince Erik of Denmark."

The big event of the 1924 social season was the wedding of Booth's grand-daughter Lois, to Prince Erik of Denmark. They were married at All Saints Anglican Church in Sandy Hill and the deputy chief of police at the time, Gilhooly, said “Yesterday afternoon, every available man was pressed into service, but ten men could not handle a crowd of ten thousand, 90% of whim were women who would not do as they were told but smiled and giggled all the time” (Ottawa Journal, Feb. 12,'24) J. R. Booth did not attend the wedding. There was no fairy tale ending to the wedding. The couple had two children but Prince Erik arranged an annulment of the wedding because of a friendship between Lois and Thorkeld Julesberg, the Prince's secretary. Lois married Julesberg after the annulment, bu t died in Denmark in 1941. Her body was transported back to Canada and she was buried in Beechwood cemetery Her father's home was at 285 Charlotte St., and was eventually sold to the Soviet government for their Embassy. The old building burned down on January 1, 1956, because the Embassy staff refused to allow Ottawa firefighters access to “Soviet Territory”!

So ends one of the interesting stories about Ottawa history, of a “poor boy” who made good and whose money was able to advance his family to the highest levels of society.

One final comment—on the day after the wedding, the bride's father joked that he was naming himself the Count de Cost for the proceedings. After his death in Dec. 1925, at his request, J.R. was buried in a relatively simple ceremony but crowds still lined the streets to honour the “Old man of the lumber industry”

Cliff Scott, an Ottawa resident since 1954 and a former history lecturer at the University of Ottawa (UOttawa), he also served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the Public Service of Canada.

Since 1992, he has been active in the volunteer sector and has held executive positions with The Historical Society of Ottawa, the Friends of the Farm and the Council of Heritage Organizations in Ottawa. He also inaugurated the Historica Heritage Fair in Ottawa and still serves on its organizing committee.

Yet More on Gouzenko - The Red Menace

5 September 1945

On Wednesday evening, 5 September 1945, Igor Gouzenko, a cipher clerk from the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa, defected, or at least tried to defect as it took him almost two days to convince anybody that he was serious. He first showed up at the office of the Ottawa Journal with secret documents that he had smuggled out of the embassy. But the city editor was busy and told Gouzenko to come back the following day. He then tried the office of Louis St. Laurent, then the Minister of Justice. But the minister and his staff had long gone home for the night. Again, Gouzenko was told to return in the morning. After going back to the Journal for another fruitless attempt to attract somebody’s attention, Gouzenko returned to his Somerset St apartment building. Terrified that he was being followed by Soviet operatives, Gouzenko, his wife and young child, took shelter with a neighbour. This was a wise decision as later that night members of the Soviet Embassy broke down the front door of their apartment looking for them.

Fortunately, the break-in brought Gouzenko to the attention of the Ottawa police who asked for guidance from the RCMP. The Mounties called Norman Robertson, the Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, who in turn conferred with Sir William Stephenson, the diminutive, Canadian-born, British spy chief, code-named “Intrepid.” Gouzenko and his family were finally “brought in from the cold” on Friday, 7 September and whisked away to a secret location outside of Oshawa for debriefing. The documents he brought with him were breathtaking. They provided details of a Soviet spy ring in Canada. Its objective was to obtain intelligence about the U.S. atomic bomb which the Americans had just dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Ottawa was an ideal locale for spies. Its National Research Council was a major weapons research centre during the war. Its scientists, along with their British and U.S. counterparts, worked on “the bomb” in secret laboratories at the University of Montreal. Canada was also the source of the uranium fuel for the weapon, and had built a top-secret nuclear reactor at Chalk River, a tiny community 180 kilometres northwest of Ottawa.

The reasons for Gouzenko’s defection were straightforward. He had been a committed Stalinist when he had arrived in Canada via Siberia in 1943. Although living conditions in the Soviet Union were difficult, he had been told that conditions were worse in the capitalist countries. However, he was shocked to discover Canadian stores stocked with goods that Soviet citizens could only dream of. Ordinary Canadian workers lived in their own houses and drove cars, unthinkable in Soviet Russia. He was also dumbstruck that people freely spoke their minds about their government without fear of arrest. After two years in Ottawa, he could not face returning to the Soviet Union.

The Canadian government’s initial response to Gouzenko’s defection was lukewarm owing to fears about upsetting the Soviets, key wartime allies. Prime Minister Mackenzie King did, however, personally inform U.S. President Truman and British Prime Minister Attlee of Gouzenko’s defection and the contents of the documents that he had brought with him. But the news was kept under wraps for months.

Rumours of a Soviet spy ring operating in Canada began to circulate in the United States on 4 February 1946. With the news about to break, King briefed his Cabinet the following day and established a Royal Commission headed by two Supreme Court Justices, Roy Kellock and Robert Taschereau, to examine the evidence and allegations made by Gouzenko. The Commission immediately began secret hearings. On 15 February, the RCMP arrested thirteen men and women named in the Soviet documents. More arrests were to follow. Later that day, the government made an official announcement to the public. Still protective of Soviet feelings, it did not mention the Soviet Union by name, saying only that secret and confidential information had been disclosed to “some members on the staff of a foreign mission in Ottawa.”

The news burst like a bombshell. The Globe and Mail’s headline the next day screamed “Atom Secret Leaks to Soviet, Canadians Suspected.” Canadian public opinion which had been very favourable towards the Soviet Union because of its role in defeating Hitler swung sharply negative. On the basis of documents and testimony gathered by the Royal Commission, twenty-three persons who mostly worked for the military, government, or Crown agencies were arrested. Eleven were subsequently found guilty of spying, including Fred Rose, the communist Member of Parliament for the Montreal riding of Cartier. He was expelled from Parliament in 1947 and sentenced to six years in prison. Allan Nunn May, a British physicist working on the bomb project in Montreal, was tried in the United Kingdom and received a sentence of ten years hard labour. Several others also received prison terms. However, courts later dismissed charges against more than half of those publicly accused by the Commission. Several had only been members of study groups, a popular activity in wartime Ottawa, which had discussed Marxism and other left-wing subjects.

The King Government’s handling of Gouzenko’s defection marked a low point for Canadian civil liberties. Suspected spies were arrested on the basis of a secret order-in-council. Their basic right of habeas corpus were suspended. Suspects were held indefinitely without legal council and without a court able to challenge their detention. Justices Kellock and Taschereau were harsh with witnesses. At times, they seemed to forget that their mission was to collect the facts and not to be judge and jury. The accusations they publicly levelled against many who were later exonerated ruined reputations and destroyed careers.

The Gouzenko affair marked the beginning of the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the Western democracies that was to last until the fall of the Berlin War in 1989. News of Soviet spies in North America fuelled growing U.S. anxieties about Soviet activities at a time when the Russians were consolidating their grip on Eastern Europe. On 5 March 1946, three weeks after the Gouzenko affair became public, Winston Churchill famously said that “an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” Also that year, Joe McCarthy was elected junior senator for Wisconsin. In 1950, he catapulted to infamy with his unsubstantiated claim of hundreds of communists working in the U.S. federal bureaucracy. The communist witch-hunts subsequently orchestrated by the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities blighted countless lives. We now have a word for this—McCarthyism. And it all began that warm September evening in Ottawa.

Sources:

Bothwell, R. & Granastein, J.L., 1981. The Gouzenko Transcripts: The “Evidence Presented to the Kellock-Taschereau Royal Commission of 1946,” Deneau Publishers & Company, Ottawa.

Edmonton Journal, 1948. “Gouzenko Tells His Own Story,” 8 May.

The Globe and Mail, 1946. “Atom Secret Leaks to Soviet, Canadians Suspected,” 16 February, 1946.

Clément, Dominque, 2014. “The Gouzenko Affair,” Canada Civil Rights Histor.

——————, 2004. “It is Not the Beliefs but the Crime that Matters: Post-War Civil Liberties Debates in Canada and Australia,” Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, No. 86, May.

Image: Library and Archives Canada, creator unknown.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

The Gouzenko Affair

June 1943

By Andrew Kavchak

On the eve of World War Two the Nazis and the Soviets signed a “non-aggression pact” (August 23, 1939) and started the war with the invasion and partition of Poland in September, 1939. Following the Nazi invasion of the U.S.S.R. in 1941, the Soviets were engaged with the western allies in a joint effort to defeat Hitler. Canada and the U.S.S.R. established relations, and the Soviets opened an embassy in Ottawa. However, the embassy proved to be a major centre of espionage and intrigue against Canada and its allies.

Igor Gouzenko was born just outside of Moscow in 1919. At the start of World War Two, he joined the Red Army and was trained as a lieutenant in military intelligence operations. In June 1943, he was stationed in Ottawa, where for over two years as a clandestine cipher clerk at the embassy. He deciphered incoming messages from Moscow and enciphered outgoing messages for the Red Army intelligence. His position gave him knowledge of Soviet espionage and infiltration activities in Canada and he became aware of Soviet agents active in numerous Canadian government offices, including the House of Commons, national defence, and external affairs. He also became aware of Soviet penetration of the Manhattan Project (the U.S. effort to develop the atom bomb).

Igor Gouzenko, circa 1946Gouzenko found life in Ottawa, where he lived with his wife and infant son, to be a stark contrast to the lives of people in the Soviet Union, and the false propaganda which he and his fellow Soviets were subjected to about the West. Knowing that Stalin was infiltrating his western allies, as well as trying to develop an atomic bomb, was disturbing to Gouzenko, particularly as the espionage and infiltration increased after the defeat of the Nazis in May, 1945.

Igor Gouzenko, circa 1946Gouzenko found life in Ottawa, where he lived with his wife and infant son, to be a stark contrast to the lives of people in the Soviet Union, and the false propaganda which he and his fellow Soviets were subjected to about the West. Knowing that Stalin was infiltrating his western allies, as well as trying to develop an atomic bomb, was disturbing to Gouzenko, particularly as the espionage and infiltration increased after the defeat of the Nazis in May, 1945.

The Japanese formally surrendered to the Americans on the deck of the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945. Just three days later, on September 5, 1945, Igor Gouzenko walked out of the Soviet embassy with 109 documents detailing the extent of Soviet espionage in Canada. For forty-eight hours no one at the offices of the Ottawa Journal would listen to him, and he was refused access to the Minister of Justice. Gouzenko could not return to the embassy and instead hid in a neighbour’s apartment (at 511 Somerset Street, across from Dundonald Park) with his family, while Soviet security officials broke into his apartment looking for him. At that point the RCMP finally listened to him.

As a result of Gouzenko’s defection, Prime Minister Mackenzie King informed U.S. President Harry Truman and British Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the new challenges posed by Stalin. A Royal Commission of Inquiry was established here in 1946 and twenty-six Soviet agents were arrested and prosecuted for treasonous activities. Approximately half were convicted.

While the world expected the end of the war to result in a period of peace, a new Cold War had begun. The “Gouzenko Affair”, which occurred in Ottawa, was thus the first significant international incident of the Cold War.

In 2003, the City of Ottawa unveiled a historic plaque in Dundonald Park across from the building where Gouzenko lived at the time of his defection, and in 2002, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated the “Gouzenko Affair” as an event of national historic significance and unveiled a corresponding plaque in the park in 2004.

(Editor’s note: Mr. Kavchak was especially involved in lobbying for the placement of the plaques in Dundonald Park.)

A "Canadian" Princess

19 January 1943

If there ever was a time for an emotional pick-me-up, you couldn’t have found a better moment than mid-January 1943. It was brutally cold, and Canada was in its fourth year of war with the Axis Powers with no end in sight. Hundreds of thousands of Canada’s young men and women had left their homes, families and jobs to serve in the armed forces, or in the merchant marine bringing much needed food and other supplies to embattled Britain. Coupon rationing for gasoline and tires had been introduced the previous spring and had been extended through 1942 to cover many food staples, including sugar, tea, coffee and butter. And it was only to get worse. On 19 January 1943, Ottawa’s Evening Citizen reported that meat rationing was about to be introduced. “Bacon, ham and even pork sausage [was] unable to be had for love or money in many places.” The butter ration was also about to be reduced by a third to 5 1/3 ounces per week per person. But there was one piece of news that bleak mid-winter that raised spirits and boosted the morale of a war-weary population. At 7pm on that snowy January day, a princess was born at Ottawa’s Civic Hospital, the third daughter of Princess Juliana of the Netherlands.

Three years earlier in May 1940, the Dutch Royal Family had fled to Britain from the Netherlands, one step ahead of the invading German army. While Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch Government established a government-in-exile in London, her daughter, Crown Princess Juliana, and her two young daughters, Princess Beatrix, aged 2 ½ years and Princess Irene, 9 months, were evacuated to Canada. Her German-born husband, Prince Bernhard, now a Dutch subject, was stationed in London becoming an active RAF spitfire pilot.

Princess Juliana and her two daughters arrived in Halifax on 11 June 1940 on a Dutch cruiser. She had been offered asylum by Canada’s new governor general, the Earl of Athlone. His wife, Princess Alice, was an aunt of Princess Juliana. After staying temporarily at Rideau Hall, the Governor General’s residence, the young family settled in Ottawa at 120 Landsdowne Road in Rockcliffe Park. They dubbed their home “Nooit Gedacht,” meaning “Never Imagined.” Princess Juliana later leased Stornaway at 541 Acacia Drive, now the official residence of the Leader of the Opposition.

In September 1942, Prince Bernard announced over Radio Orange that Princess Juliana was pregnant with their baby due sometime in late January the following year. In anticipation of the royal birth, the Canadian Government declared in December the hospital room in the Civic Hospital where the birth was to occur “extraterritorial” to ensure that the child would not be born a Canadian citizen and British subject; an important consideration should the child be a boy and hence heir to the Dutch throne.

Four rooms were set aside for Princess Juliana on the third floor of the Civic Hospital—one room for Princess Juliana, one room for the baby, another for her nurse, and a fourth for a security guard. Fittingly, the rooms overlooked Holland Avenue. The corridor outside of the rooms was also decorated with the Dutch flag.

Suffering from mumps and with the birth due anytime, Princess Juliana was admitted to hospital by her physician, Dr. Puddicombe, on Monday, 18 January 1943. Princess Margriet Francisca, the first and only North American-born princess, was born the following day. She was named after the marguerite, a daisy-like flower and symbol of Dutch resistance. Prince Bernhard who flew to Ottawa for the birth reported the glad tidings by telephone via Montreal and New York to Queen Wilhelmina in London. The news was then sent to reporters waiting at the Château Laurier Hotel, and broadcasted around the world.

At 7.45pm, the Civic Hospital released its first press statement saying that both mother and daughter were doing well, with the new princess weighing in at seven pounds, five ounces. The next day, the Peace Tower carillon on Parliament Hill played the Dutch National Anthem and other Dutch songs, while the Dutch tricolour flew overhead; the first time a foreign flag had flown from the Tower. In keeping with Dutch tradition, the baby’s birth was celebrated by eating beschuit met muisjes—a rusk topped with sugar and anise seed sprinkles. Typically coloured white and pink, the sprinkles were coloured orange in honour of the Dutch Royal House of Orange-Nassau. The rusks were wrapped in orange paper and tied with a red, white and blue ribbon. A journalist described one as “hard as a chunk of the city’s ice encrusted pavement” but “with rationing what it is” it tasted “pretty good.”

News of the princess’s birth, was a major morale boost for oppressed Dutch citizens living in occupied Netherlands. The underground Dutch newspaper De Oranjerkrant wrote: “Little Margriet, you will be our princess of peace. We long to have you in our midst…Come soon Margriet. We are awaiting you with open arms.”

Princess Margriet was christened in St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church on Wellington St on 29 June 1943 at 1:00pm. It was a bright, sunny afternoon. Among the dignitaries in attendance for the occasion were her father, Prince Bernhard, her grandmother, Queen Wilhelmina who was making her second trip to Ottawa, the Governor General and his wife, and Prime Minister Mackenzie King. The packed service was conducted in Dutch by Rev. Dr Winfield Burggraaff, a Dutch naval chaplain and a minister of the Reformed Church on Staten Island, NY. Also presiding were Rev. A. Ian Burnett, minister of St. Andrew’s and Rev. Robert Good, former moderator of St. Andrew’s. Godparents for the little princess included U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, Queen Mary, the widow of King George V, the Governor General, and the entire Dutch merchant marine who were represented at the church by seven of its members. Marine Roell, who had accompanied Princess Juliana into exile in Canada, was also made a godmother, though she was identified only as a widow of a Dutch martyr who gave his life for his country in order to protect her family still in Holland from reprisals. The christening service was broadcasted by short-wave radio live to London via New York and was rebroadcasted to the occupied Netherlands. Prince Bernhard advised his countrymen not to celebrate too openly for fear of German retaliation. Following the ceremony, hundreds of Ottawa citizens welcomed the little princess with loud applause as the Royal Family emerged from the church.

The Dutch Royal Family stayed in Ottawa for the remainder of the war, returning to the Netherlands in early May 1945 after its liberation for the most part by Canadian troops. Before leaving, Princess Juliana gave an oak lectern to St Andrew’s Church carved with the royal coat of arms, marguerites, and the four evangelists. The birth of Princess Margriet helped cement a lasting bond between the peoples of Canada and the Netherlands. Princess Juliana is reported to have said “My baby will always be a link with Canada not only for my own family but for the Netherlands.” As way of thanks for her family’s treatment in Canada, Princess Juliana sent 100,000 tulips to Ottawa in the fall of 1945. It was the start of a beautiful friendship that has lasted to the present day.

Sources:

CBC Digital Archives, 1943: Netherlands’ Princess Margriet Born in Ottawa, goo.gl/D008s1.

Het Koninklijk Huis, Princess Margriet, goo.gl/LFutjK.

The Evening Citizen, 1940. “Crown Princess of Netherlands Reaches Canada,” 11 June.

——————–, 1943. “Wider Powers for Economy Controller, Meat Rationing to Include Pork, Lamb and Veal,” 19 January.

———————, 1943. “News of Birth of New Princess Flashed to Royal Grandmother,” 20 January.

———————, 1943. “Third Daughter Born to Princess Juliana Early Tuesday Evening,” 20 January.

———————, 1943. “Butter Ration for Next Six Weeks Cut by Third,” 20 January.

———————, 1945. “Gift of Bulbs to Commemorate Great Friendship,” 3 October.

VanderMay, Andrew, 1992. When Canada was Home: The Story of Dutch Princess Margriet, Vanderheide Publishing Co. Ltd, Surray, B.C.

Image: goo.gl/l7r03B.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

The Maharaja of the Keyboard

5 December 1945

In the firmament of great jazz musicians, few stars sparkle as brightly as that of Oscar Peterson. Born in 1925 to a hard-working, immigrant family from the poor St Henri neighbourhood of Montreal, Peterson burst like a fiery comet onto the jazz scene while still a teenager. Over a career that spanned more than 60 years, Peterson wowed audiences around the world with his prodigious piano technique, his amazing talent for improvisation, and a range that encompassed everything from the classics to stride, blues, boogie and bebop. He played with all the jazz greats of his age, including trumpeters, Louis Armstrong, Roy Eldridge, and Dizzy Gillespie, saxophonists Charlie Parker and Lester Young, and such famed vocalists such as Sarah Vaughn, Billy Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald. Demonstrating his range, he also accompanied such artistic luminaries as Fred Astaire, and the great violinist Itzhak Pearlman. It was Roy Eldridge who dubbed Peterson the “Maharaja of the Keyboard. Louis Armstrong called him “the man with four hands.” As well as playing the piano, Peterson was a talented composer, and had a singing voice comparable to that of Nat King Cole. His best known compositions are the Canadiana Suite, an album released in 1964, and Hymn to Freedom, composed in 1962. Oscar Peterson and his trio played Hymn to Freedom in 2003 at a gala in Canada to celebrate Queen Elizabeth’s Golden Jubilee. In 2008, the Hymn was played at U.S. President Obama’s inauguration.

Jazz was in Peterson’s blood. Both his parents, Daniel and Olive Peterson, had a passion for music, and encouraged their five children to learn instruments. A tight family budget was stretched to include a piano. Daniel Peterson, a self-taught piano player, instructed his wife and their five children how to play. Young Oscar initially studied the trumpet as well as the piano. But after a lengthy bout with tuberculosis in the early 1930s, which claimed the life of his older brother Fred, Oscar concentrated on the piano. Father Daniel was a demanding teacher, insisting on daily practice and assigning musical homework for his children while he was absent working as a porter on the railway. But Oscar, with his perfect pitch and ability to play songs by ear, was up to the challenge. Later, his older sister Daisy became his piano instructor. His first exposure to jazz came from listening to radio. His father, however, looked down on jazz seeing it as music for the uneducated. He insisted that Oscar learn the classics. Peterson later studied under two classically-trained pianists, Lou Harper and Paul de Marky, the latter was Canada’s most acclaimed classical pianist of the time who taught music at McGill University in Montreal. He also instructed private students, charging $15 hour, a huge sum for Oscar’s parents (equivalent to more than $200 in today’s money). From a very early age, Oscar played in churches, community centres, and schools. It was in such venues, Oscar began to learn how to improvise.

Peterson’s first big break came in 1940 when he auditioned for an amateur music contest hosted by CBC radio. He went on to win not only the Montreal competition but also the national finals held in Toronto. He was only 15 years old, and the only black contestant. He received a cheque for $250 (close to $4,000 today). From there, there was no looking back. He quickly out-grew his Montreal High School band, the Victory Serenaders, and gigs in the school gym. In 1943, he dropped out to play full-time in a popular Montreal big band led by the trumpet player Johnny Holmes after a spot for a pianist opened up when the group’s regular pianist was drafted into the army.

Peterson received further national exposure in 1945 when RCA Victor, one of Canada’s largest recording studios agreed to record him, releasing two 78 rpm records. They were hugely successfully. In early June 1945, Freiman’s Department Store on Rideau Street advertised in The Ottawa Journal “A new VICTOR ‘discovery’ for your piano pin-up collection. Name: OSCAR PETERSON, just a youngster of eighteen, a Canadian lad of inspired rhythm that flows from his fingertips in a sparkling, ear tingling, original style all his own.” The store encouraged people to come listen to a sample recording of I Got Rhythm at Freiman’s Record Studios located on the third floor of the department store, daring them to try to keep their toes quiet!

Peterson’s first known public performance in Ottawa took place on Wednesday, 5 December 1945 at the Glebe Collegiate Auditorium at 8.30pm. The performance called Hot Jazz, featured Oscar Peterson and his jazz trio: Peterson on the piano, Russ Dufort on drums, and George Murphy on bass. The prices of admission was 90 cents, $1.20, and $1.50. The trio played to a capacity crowd, with people standing two and three deep at the back of the auditorium. Extra seats were placed on the stage. Students from Carleton College’s (later Carleton University) sat or stood behind the stage, so that they could at least hear the music even if they couldn’t see the artists. The Ottawa Journal reporter described the twenty-year old Peterson as “one of the foremost exponents of jazz.” The night’s programme featured both classical pieces such as Chopin’s Polonaise as well as jazz pieces, including Duke Ellington’s C Jam Blues and Peterson’s own composition “The Boogie Blues.” The enthusiastic crowd gave the trio three encores. At one of the encores, Peterson played the Sheik of Araby that he had recently recorded. The journalist concluded by saying that Peterson’s boogie-woogie was “probably the best heard in Ottawa for some time.” The trio returned to the Glebe Collegiate the following May. More than 1,200 people crammed into the school auditorium to hear them again perform a selection of classical and jazz numbers, including Peterson’s own compositions.

Between these two Ottawa performances, Peterson made his debut at the prestigious Massey Hall in Toronto in early March 1946. Most of the audience that night had only heard Peterson through his records. As in Ottawa and elsewhere, the crowd was dazzled by his technique and imagination; Oscar Peterson had made it to the big time. Appearances on the CBC radio series Canadian Cavalcade cemented his reputation for being the country’s most popular, up-and-coming, young artist. He made his American debut in 1949 at Carnegie Hall in New York City, where he played alongside Dizzy Gillespie, Buddy Rich, and Ella Fitzgerald. Peterson had been “discovered” by music promoter Norman Granz who had been in Montreal for a meeting. Hearing Peterson play on the radio, Grantz, who produced the “Jazz at the Philharmonic (JATP)” series of concerts, tours, and recordings, invited him to perform in New York. From then on, Oscar Peterson was an international star. In 1950, Grantz, who later became Peterson manager, signed him to a contract to perform with JATP. Over the following decade, Peterson participated in fifteen, cross-continent JATP tours. Peterson’s business relationship and friendship with Granz lasted until the latter’s death in 2001.

Over the decades, Peterson performed in a number of small groups, usually trios. During the 1950s, the other two members of the group were Ray Brown on bass, and Herb Ellis on guitar. In 1958, Ellis left the trio and was replaced by drummer Ed Thigpen. During the 1970s and 1980s, Peterson played with Joe Pass on guitar and bassist Niels-Henning Pederson. In the late 1990s, Peterson formed a quartet, with Pederson on bass, Martin Drew on drums, and Ulf Wakenius on guitar.

Statue of Oscar Peterson by Ruth Abernethy, unveiled by HM Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh on June 30, 2010 in front of 10,000 cheering spectators

Statue of Oscar Peterson by Ruth Abernethy, unveiled by HM Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh on June 30, 2010 in front of 10,000 cheering spectators

National Arts Centre, Ottawa, January 2016Although successful from an early age, Oscar Peterson faced major challenges, not least of which was the racism that he confronted, especially when he toured the U.S. south during the 1950s and 1960s. Even in Canada, he had to endure discrimination, with hotels unwilling to hire black musicians. On one highly publicized occasion in 1951, he was denied a haircut in Hamilton, Ontario owing to his colour. The city’s mayor later apologized. In his quiet, understated way, Peterson fought back. He wrote his Hymn to Freedom in support of the civil rights movement. He was also instrumental in Canadian television advertising becoming more inclusive of minorities. Peterson’s home life also suffered from his constant touring. He was married four times. He also largely missed out on seeing his seven children grow up. Late in life, after suffering a stroke while performing in New York, his ability to use his left hand was impaired. Peterson fought through depression, and continued to perform to adoring audiences. He passed away from kidney failure on 23 December 2007 at 82 years of age.

During his lifetime, Peterson received many honours. Sixteen universities, including Carleton University, awarded him honorary doctorates. From 1991-94, he was Chancellor of the University of York in Toronto. He also received eight Grammies from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, including a lifetime achievement award in 1997 for his more than 200 records. In 1972, he was made an Officer of the Order of Canada, and was promoted to Officer of the Order in 1984. In May 2010, just over two years after his death, Queen Elizabeth unveiled a statue of Oscar Peterson seated at his piano outside of the National Art Centre, a place where he had played many times during his long and productive career.

Sources:

Batten, Jack. 2012. Oscar Peterson: The Man and His Jazz, Tundra Books: Toronto

Globe and Mail, 1946. “Swing Pianist Stirs Massey Hall throng,” 8 March.

——————-, 2007. “Oscar Peterson, Musician, ‘Man with four hands was one of the greatest piano players of all time.” 26 December.

Ottawa Journal, (The), 1945. “Freiman’s platter chatter,” 7 June.

—————————, 1945. “Hot Jazz.” 5 December.

————————–, 1945. “Peterson played to packed audience in Glebe, 6 December

————————–, 1946. “Oscar Peterson Plays to 1,200.” 10 May.

Marin, Riva, 2003. Oscar: The Life and Music of Oscar Peterson, Groundwood Books: Toronto.

Milner, Mike, 2012. “Frank Sinatra, Oscar Peterson and the maharaja of the keyboard,” CBC Music, goo.gl/hDVvlF, 6 March.

Peterson, Oscar, 1964. Hymn to Freedom, YouTube: goo.gl/gRDt1b.

Images:

Oscar Peterson in 1977, Author Tom Marcello, New York, U.S.A., goo.gl/ZcpyN0.

Oscar Peterson statue at the National Arts Centre, 2016 by James Powell.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

The Jersey Lily

8 November 1883

During the early 1880s, the population of Ottawa, while growing rapidly, totalled less than 30,000 souls, far smaller than Toronto, Montreal or Quebec City. But being the capital of the new Dominion of Canada, and therefore home to the Governor General and Parliament, what the community lacked in numbers it made up in political and social clout. The town also boasted a small but wealthy group of industrialists who had mostly made their fortunes in the forestry industry. Because of these political and economic elites, Ottawa enjoyed the amenities of a far larger city, including the luxurious Russell Hotel, Ottawa’s premier hostelry, and the Grand Opera House, a top-quality hall for theatrical and other performances. With such facilities, Ottawa was equipped to welcome the international celebrities of the age, including the witty Oscar Wilde, the divine Sarah Bernhardt, and the incomparable Mrs Lillie Langtry. Mrs Langtry, a.k.a. “The Jersey Lilly,” captivated audiences on both sides of the Atlantic for more than forty years. She made three visits to Ottawa during her career, the first occurring on 8 November 1883.

Mrs Lillie Langtry was born Emilie Charlotte Le Breton, in Jersey, one of the Channel Islands, in 1853, the daughter of a prominent clergyman. While brought up in a liberal, loving family, island life was confining for the beautiful young girl, known to everyone as “Lillie.” To get off the island and experience a taste of adventure, she married Edward Langtry in 1874, a widower ten years her senior. The couple settled in London. Sadly, the marriage quickly soured. Husband Edward drank heavily, and lived beyond his means. Although he had two racing yachts, his family’s wealth had been largely dissipated by the time it reached him. High living quickly went through the remaining fortune.

Lillie Langtry’s society career was launched when she was introduced to the artist John Everett Millais, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a non-conformist group of Victorian artists who aimed to revive a medieval, artistic aesthetic. Attracted by her great beauty and charm, she became the muse of the Pre-Raphaelites, posing for Millais, George Francis Miles, and others, including Sir Edward Poynter. Oscar Wilde also became a close friend and mentor, introducing her to his friends in the Aesthetics Movement, including the American artist, James Whistler.

Mrs Langtry arrival in society coincided with photography going mainstream, and the beginning of a mass celebrity culture. Joining the ranks of the “Professional Beauties,” her photograph graced the store fronts and middle-class sitting rooms of Britain. As part of this elite group, Langtry gained an entreé into the dining rooms and ball rooms of the aristocracy ever eager to seek out the latest sensation. Male admirers, known as “Langtry’s lancers,” followed her as she rode daily in Hyde Park, a popular society past time that provided an opportunity to see people and be seen. In 1877, she caught the philandering eye of Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales, the oldest son of Queen Victoria. The married prince and Mrs Langtry began a well-publicized affair that raised her to the pinnacle of British society. Although the relationship cooled after a time, and the prince looked elsewhere for extra-marital affection, they remained close friends. On his coronation as Edward VII in 1902, Mrs Langtry, along with other former mistresses, attended the ceremony at Westminster Abbey in a special box, known sotto voce as the “King’s Loose Box.” After the prince, Mrs Langtry went on to have many other affairs that brought her considerable notoriety, including one with Prince Louis of Battenberg, a close friend of the Prince of Wales. Prince Louis is reputed to have been the father of Mrs Langtry’s only child, a daughter, Jeanne Marie, though she was also in a relationship with another man at the time.

In 1881, with the Langtrys close to bankruptcy, Lillie embarked on a stage career on the advice of Oscar Wilde, after taking acting lessons from the English actress Henrietta Hodson, the mistress and later wife of the politician Henry Labouchère. (As an aside, Labouchère’s uncle, also Henry, was the person who conveyed Queen Victoria’s choice of Ottawa as the capital of Canada to Sir Edmund Head, the Governor General, in 1857.) The theatre was a daring career decision. In the late nineteenth century, acting was not viewed a proper vocation for gentlewomen. Actresses were often looked upon as little more than prostitutes. Mrs Langtry’s stage career, which was supported by the Prince of Wales, helped to change attitudes. She also broke convention by handling all her bookings herself, as well as hiring a theatre troupe.